The update of The Twilight Zone had me at “What dimension are you even in?”

The more I think about it, the more excited I am, because I think the time is perfect for The Twilight Zone to come back. Our current reality is a fractured and terrifying place, with some forces trying to recreate the exact 1950s fauxtopia that Rod Serling railed against in the original version of The Twilight Zone, while other forces are trying to drag us into what might, if we’re very lucky, turn out to be a sustainable future. We have technology and innovation that make us, essentially, gods—and once we get that pesky mortality thing beat we will be unstoppable—except, of course, that human nature is probably going to screw us over at every turn.

And that’s where the original Twilight Zone was so good: Serling knew that to reckon with human nature was to ricochet between unbearable depths and impossible heights. In order to reflect that, his show had to balance demands that humans do better, already, with shots of pure hope. He knew to lighten his moralizing with occasional pure silliness. The show keeps coming back in new formats because something in this combination speaks to people, and each new reboot spends at least some time on that foundation of social justice that Serling laid back in the 1950s.

The first iteration of The Twilight Zone was born from frustration. When Rod Serling took a chance and moved out to New York to start writing for television, he believed that TV could matter, that a writer could use the medium to tell important stories, and that it was a direct way to reach a mass audience that might not have the resources for live theater or the time for movies. And, for a few years, this worked. Those of you who have grown up on sitcom pap and formulaic procedurals were probably justifiably startled when the Golden Age of TV began to happen around you, so I can only imagine your shock when I say that television used to be considered a vehicle for serious, well-written teleplays—live broadcasts, usually about an hour long, that were original to TV and written by respected authors. Programs like Playhouse 90 and The United States Steel Hour gave a platform to dozens of young writers, and Serling soon became one of the most respected. The word he tended to use in interviews about his work was “adult” (this turned out to be a telling adjective, given how often people liked to dismiss SFF as kids stuff or childish). He wanted to tell “adult” stories about real people, and in the early years of TV it largely worked.

Teleplays could reach a mass audience to tell stories of working-class people trying to make it in an uncaring world. But after only a few years, the mission of these shows was undercut by skittish sponsors who didn’t want writers to say anything too controversial. It’s hard to sell soda and toilet paper during a poignant drama about racism or poverty, and Serling often fought with higher-ups over his scripts. A breaking point that he spoke of many times was his attempt, in 1956, to write a piece about the torture and murder of Emmett Till. The script for “Noon on Doomsday” (to be an episode of The United States Steel Hour) was finally “sanitized” beyond recognition because the executives didn’t want to offend their sponsor, the Atlanta-based Coca-Cola Company. The locale was changed to New England, the victim became an adult Jewish man, and no one watching the show would guess it had anything to do with the original crime.

Would it have fixed things for a major, majority-white television network to allow their Jewish star writer to deal directly with the racist murder of a Black child? Of course not. But an enormous audience of Black viewers (not to mention socially progressive viewers of all races) would have seen a giant corporation putting their money into telling that story rather than twisting it into a feel-good parable that had no relation to modern life.

This happened repeatedly. Serling, that particularly sad example of a writer who has been cursed with a moral compass, tilting at sponsors and censors over and over again, and winning multiple Emmys for the teleplays he wrote that were about working-class white people. Tough-minded, jaw-clenched drama of the sort white TV owners could watch, empathize with, and feel like they had been moved, without the pesky side effect of looking at society any differently when they set off to work or school or errands the next morning.

But thanks to those Emmys, Serling was able to convince CBS to make The Twilight Zone. And plenty of people thought he was nuts to go into “fantasy.” Just check out this Mike Wallace interview from 1959, where Wallace asks him if he’s gone nuts in between great gasping lungfuls of cigarette smoke, literally saying that by working on The Twilight Zone Serling has “given up on writing anything important for television.”

But Serling knew better. When Wallace calls them “potboilers,” Serling claims that the scripts are adult, and that at only a half hour he wouldn’t be able to “cop a plea” or “chop an axe”—put forward a social message. Of course that was all so much smoke, because with the shiny veneer of fantasy, and a sprinkle of aliens or time travel, The Twilight Zone could call white people on their racism. It could call the audience on their complicity towards anti-Semitism, or force them to relive the Holocaust, or pre-live the nuclear annihilation that everyone thought loomed on the horizon. (It’s probably still looming, by the way.) It could walk its viewers through the damaging effects of nostalgia, or point out the dangers of conformity. All the things that made up late ’50s-early ’60s society – The Twilight Zone could poke all of it with a stick and flip it over and look for the centipedes underneath.

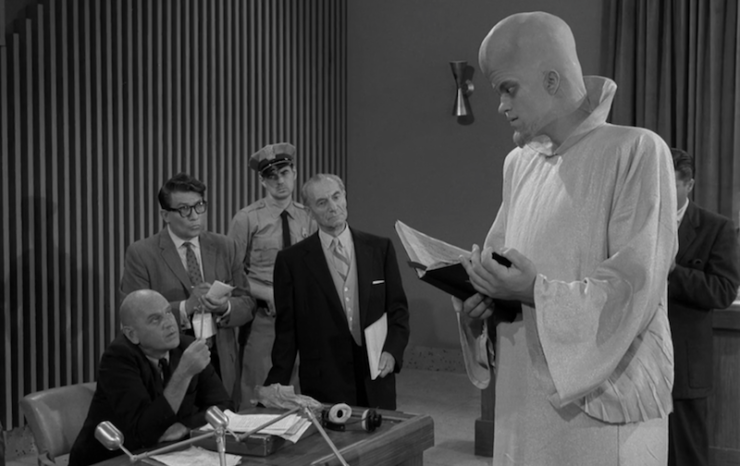

Over the course of its five seasons, Serling wrote or co-wrote 92 of the show’s 156 episodes, and while always telling good tales, he used the hell out of his platform. In addition to racism, anti-Semitism, conformity, and nuclear paranoia, the show dealt with internalized misogyny, sexual harassment (before the term itself existed), class divisions, and, in general, a fear of the Other. It’s that fear of the Other than makes the show so unique, because while occasionally the Other was a shipful of Kanamits, swinging past Earth to grab some human meat like our planet was nothing more than a Taco Bell drive-thru, many of the episodes posited either that the aliens were benevolent and peace-loving, or that The Real Monster Was Man.

“The Monsters Are Due On Maple Street,” “The Shelter,” and “The Masks” are just a few of the episodes that deal with paranoia, greed, and the primal nature that lurks beneath civilization’s all-too-thin veneer. “Number 12 Looks Just Like You” is about internalized misogyny. 1960’s “The Big Tall Wish” is just a regular wish fulfillment fantasy… except the main cast are all Black characters, playing out a whimsical story that isn’t “about” race, which did not happen too often on TV in 1960.

“He’s Alive” and “Death’s-Head Revisited” both dealt with Hitler and the Holocaust at a time when that horror wasn’t often discussed on mainstream television aimed at Protestant and Catholic Americans. “Death’s-Head” even ends with Serling using his closing narration to deliver a stirring explanation of why Holocaust Centers concentration camps need to be kept up as reminders of our history:

They must remain standing because they are a monument to a moment in time when some men decided to turn the Earth into a graveyard. Into it they shoveled all of their reason, their logic, their knowledge, but worst of all, their conscience. And the moment we forget this, the moment we cease to be haunted by its remembrance, then we become the gravediggers.

Three years later, Serling penned a response to the assassination of John F Kennedy. “I Am the Night—Color Me Black” was something of an update of an earlier teleplay “A Town Has Turned to Dust,” in which he had again attempted to reckon with the murder of Emmet Till—only to find himself once more making compromise after compromise to horrified sponsors. This time Serling tweaked the racial elements by centering the story on a man, seemingly white (and played by a white actor, Terry Becker) who has killed another man and is to be executed for it. He claims it was self-defense, most of the town is against him, he is publicly hanged. When the sun doesn’t rise a Black pastor argues that the (mostly white) townspeople are being judged for their hatred.

And once again, Serling doesn’t let his viewers off the hook. His final narration is even harsher than his earlier send off in “Death’s Head”:

A sickness known as hate. Not a virus, not a microbe, not a germ—but a sickness nonetheless, highly contagious, deadly in its effects. Don’t look for it in the Twilight Zone—look for it in a mirror. Look for it before the light goes out altogether.

The urgency of the original Twilight Zone, for all that it could sometimes fall into pure cheese, was that Serling and his stable of writers usually implicated viewers. The Real Monster is Man, sure, but the key is that you are the Man. You’re not just passively watching a fun, spooky TV show. You are complicit in the society around you, and whatever is wrong with that society is a result of your own action or inaction. We all know the twists, but that sense of justice is why The Twilight Zone is still relevant, and why it’s worth bringing back.

***

The Twilight Zone has come back multiple times now: once as an all-star anthology movie, and twice in television series that riffed on the original. Twilight Zone: The Movie came out in 1983, with segments directed by John Landis, Steven Spielberg, Joe Dante, and George Miller. It adapted three classic episodes, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” “Kick the Can,” and “It’s a Good Life,” along with one original, “Time Out,” and a wraparound story that’s arguably the most frightening part of the whole thing. When we consider the film’s one original segment, “Time Out,” we run into a fascinating tangle of intention and execution. Obviously any discussion of this segment is overshadowed by the horrifying helicopter accident that killed an adult actor – the star of the segment—and the two child co-stars. It’s beyond the reach of this essay to discuss it, but I do want to acknowledge it. The tragic accident forced a change to the segment that I will talk about in a moment.

After an angry white man goes to a bar and makes loud, racist complaints against Jewish coworkers, “A-rabs,” “Orientals,” a “Jap bank” and Black neighbors, he finds himself unstuck in time. He walks through the bar’s door and is suddenly in Nazi Germany, being chased by SS officers, escapes them only to open his eyes and realize he’s a Black man about to be lynched by the KKK, and then escapes that situation only to emerge into a Vietnamese jungle, being chased by US troops. The segments ends with him back in Nazi Germany being packed into a freight train to be sent to a Holocaust Center concentration camp.

Now, you can see where the segment was trying to go, but it’s very easy, in the 1980s, to invoke the Holocaust to deplore anti-Semitism, or to invoke lynching to get mainstream white people to empathize with the plight of Black people in a white supremacist society, because a middle-class white person can say, “Fuck, at least I’m not a Nazi,” or “I’m not a real racist—I think the KKK are monsters!”—that’s 101-level anti-racism work. Where it gets even knottier is the way they deal with anti-Asian sentiment by… casting him as an enemy combatant? In the script, the segment was supposed to end with the white character being returned safely to his own time as a reward for saving two children from a Vietnamese village that’s under attack by US troops—which in no way shows that he’s changed ideologically, only that he’s willing to save innocent children. This ending was changed after the accident, but I’d say that even as it stands, there simply isn’t enough specificity in the segment to work into a viewer’s mind in a way that would teach them anything.

The 1985 series skewed much more toward the silly, high concept elements of the franchise than toward social awareness. It included scripts from J. Michael Straczynski, Harlan Ellison, and George R.R. Martin, and some of the episodes adapted stories from Arthur C. Clarke and Stephen King. In addition, some episodes, including “Shadowplay,” “Night of the Meek,” and “Dead Woman’s Shoes,” were updates of classics. Most of the episodes dealt with scenarios such as: What if you played cards with the Devil? What if a bunch of kids captured a leprechaun? What if the monster under your bed came out to protect you from bullies? A lot of them are spooky or charming, but without much deeper commentary.

One episode does wrestle more pointedly with modern society. In “Wong’s Lost and Found Emporium,” a young Chinese-American man, David Wong, enters a mystical emporium full of seemingly unending shelves of trinkets, jars, and mirrors—each containing an ineffable element that a person has lost. He’s searching for his lost compassion, and tells a fellow seeker that years of racial hostility have beaten him down. He specifically cites the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, a hate crime in which a pair of unemployed white autoworkers attacked and killed a Chinese man, only to, initially, serve no time and pay only $3,000 in fines. (Supposedly, they attacked him because they mistakenly thought he was Japanese and were taking out their rage at the Japanese auto industry.) The woman agrees to help David if he’ll help her find her sense of humor, which she’s lost after years in an emotionally abusive marriage. In the end she regains her humor, but he fails to collect his compassion, and even comments that he “probably deserved” this fate. The two of them decide to stay to manage the Emporium, to help others find their things, with David hoping that this work will gradually bring back his compassion once more.

On the one hand, this is a beautiful story featuring two different characters of color, and a lengthy conversation about the Chin case. But I have to admit I’m uncomfortable when a story ends on the note that, when faced with a racist society, the object of oppression needs to dedicate his life to finding compassion, and ends his story on a note of self-recrimination when some healthy rage might be a better option. After all, one thing the original Twilight Zone was shockingly good at was honoring rage, and leaving bigots and abusers on the hook for their actions as the credits rolled.

The 2002 reboot of The Twilight Zone–this time with Forest Whitaker as the Rod Serling stand-in—tackled controversial subjects immediately and with enthusiasm: episode three revolved around a group of skinheads assaulting a Black man, and by episode five the show was sending Katherine Heigl back in time to kill Hitler.

But it also tipped a little too far into heavy-handedness. For instance, the choice to update “The Monsters are Due on Maple Street,” for an early-’00s audience still actively dealing with post-9/11/01 paranoia, was admirable. But by changing the original episode’s panic over aliens to a basic fear of terrorists the show loses that fantastical element that allowed Serling to comment without being too on-the-nose. In the original episode, the twist is that the panic really is being caused by aliens because our human ability to scapegoat each other makes us easy prey, In the 2002 redo, the twist is just that the government is messing with people and proving that we’re vulnerable to human terrorists. There’s no subtext or metatext—it’s all just text.

That early-’00s reboot also, however, gave us “Rewind”… which happens to be the title of the premiere episode of the newest Twilight Zone reboot. In the original “Rewind,” a gambler is given a tape recorder that rewinds time, and, naturally, he uses it to try to win big. (Ironic twist alert: he learns that rewinding time repeatedly has some dire consequences.) It’s also the title of the premiere episode of the latest Twilight Zone reboot, and it fills me with hope. Sanaa Lathan stars in the episode, and the glimpses from the trailer definitely imply that something goes terribly wrong between a state trooper and young Black man. But it would appear that Lathan has a Very Important Camcorder, and a voice in the trailer whispers “If we go backwards again”—so I can only assume that this is a mystical item that rewinds time. Is the newest version of Rod Serling’s classic show going to launch with an episode that tackles police violence and systemic racism? Because if so that’s going to set quite a tone for the show, which already features the most diverse cast a Twilight Zone has ever had.

Now, Jordan Peele is not the only person running this show, but Peele has proved that he has a vision. I mean, first of all—how many debut films have ever been as self-assured and whole as Get Out? And sure, he’d worked in TV for years, but that’s a very different skillset than writing and directing a movie that creates its own world, makes sure every single character is a full and complete person, balances on a knife-edge of satire and horror for every moment of its running time, roots the entire sense of horror in a deeply felt emotional truth, and introduces an instantly iconic phrase into the American lexicon. And that’s before we get into the way that it’s also a movie-long code switch, with Black and white audiences having very different responses to the film at key points.

I haven’t seen Us yet, but early reviews are saying that it is, if anything, even better than Get Out… and it was partially inspired by a classic episode of The Twilight Zone. Peele has also said that he considers The Twilight Zone “the greatest show of all time,” because, as he told io9’s Evan Narcisse, Serling “showed me and taught me that story and parable is the most effective form of communication.” In the same interview he says, “…horror that pops tends to do so because there’s a bigger picture behind the images.” All of this points to the idea that he wants the new iteration of the show to consider the deeper moral questions that the original did so well, and that the reboots at least nodded toward.

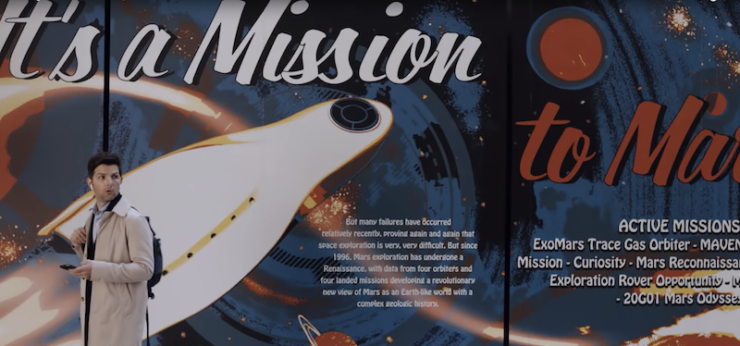

Now, as should be clear, I’m hoping that this show is free and inventive and original… but I’ve also been thinking about which classic episodes I’d like to see them adapt. Obviously we’re getting another take on “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet”—but this one seems to be a true remix, with shots in the trailer implying that the main character not only lives in a world where travel to Mars is a possibility, but also that he has an audiobook predicting his future. We’re getting an episode called “The Comedian,” which presumably won’t be a riff on Serling’s early teleplay of the same name. And it looks like we’re getting sideways references, like the Devil Bobblehead that calls back to the other classic Shatner episode, “Nick of Time.”

How fantastic would it be if the show dove into the batshit territory of a literal-battle-with-the-Devil episode like “The Howling Man”? Or the disturbing wager at the heart of “The Silence”? Personally I’d love it if the show went all-in on the more whimsical stuff like “Mr. Bevis” (eccentric young man realizes he values friendship more than material success) and “The Hunt” (dead guy refuses to enter Heaven unless his dog can come too) because part of the key to the original show’s success was the breadth of its worldview—the idea that a sweet episode could suddenly well up in the midst of episodes about horror and human depravity is just as vital as the show’s moral core.

But as for that moral core…what would it be like, in the Year of Our Serling 2019, to tune in to updated takes on “A Quality of Mercy” or “In Praise of Pip” that could reckon with the forever wars we’re still, currently, fighting? Or a riff on the climate change thought experiment “The Midnight Sun” that takes place, oh, I don’t know, right now, rather than some nebulous future? Or a post-#metoo update on “The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Ross”? I’d love a new take on “The Big Tall Wish” with an all-Syrian cast, or an update to one of the Holocaust episodes that deals with Islamophobia.

Most of all, I’m hoping that this new iteration of The Twilight Zone tells new stories, and goes in new directions, to do what its predecessor did: find unique ways to show us ourselves, and gently ask us to do better.