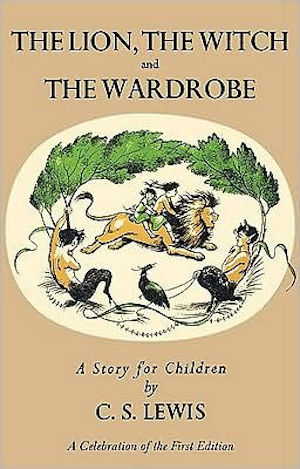

When I was a child, I had no idea what was coming when Susan and Lucy snuck out of their tents. Aslan seemed sad, and the girls wanted to see why. Aslan told them how lonely he was, and invited them to join him on his long walk—on the condition that they will leave when ordered. My first time reading The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Aslan’s words filled me with a deep and unshakeable dread. Aslan seemed to feel the same thing, walking with his head so low to the ground that it was practically dragging. The girls put their hands in his mane and stroked his head, and tried to comfort him.

When they reached the Stone Table, every evil beast of Narnia was waiting, including Jadis herself, whose long winter had begun to thaw at last. To Susan and Lucy’s horror (and mine!), Aslan had agreed to be murdered—sacrificed—upon the Stone Table, so that their brother Edmund could live.

Keeping in mind that Aslan is not a metaphor for Jesus Christ, but is the manifestation of Jesus in Narnia, this moment offers a central insight into Lewis’s beliefs about why, in their respective stories, both Jesus and Aslan die. It’s the climactic moment of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and a key event in the entire Chronicles.

For those of you who don’t have a Christian background, I’m going to break out some Christian theological terms in this article. I’ll do my best to make them accessible and understandable from a casual reading standpoint, and we can chat more in the comments if I don’t make things clear enough. For those from a heavily Christian background, please remember this isn’t a seminary paper, so we’re going to be using some shorthand.

So. Why did Aslan have to die?

The easy answer, the one that tempts us at first glance, is to say, “Because Edmund is a traitor.” Or, in Christian religious terms, “Edmund sinned.”

Here’s an interesting thing to note, however: Edmund already apologized for betraying his siblings and had a long heart-to-heart with Aslan before the events of the Stone Table. Not only that, but he had received both the forgiveness and the blessing of his brother and sisters and the Great Lion Himself.

The morning before the events of the Stone Table the other Pevensies wake to discover that their brother Edmund has been saved from the Witch. Edmund talks to Aslan in a conversation to which we are not privy, but of which we are told, “Edmund never forgot.”

Aslan returns their wayward brother to them and says, “Here is your brother, and—there is no need to talk to him about what is past.”

Edmund shakes hands with his siblings and says he is sorry to each of them, and they all say, “That’s all right.” Then they cast around for something to say that will “make it quite clear that they are all friends with him again.” Edmund is forgiven by Aslan, forgiven by his siblings, and restored in his relationship with them all.

Aslan didn’t die so that Edmund could be forgiven; Edmund had already received forgiveness.

Despite this forgiveness, however, there are still consequences to Edmund’s actions. He still betrayed his siblings (and, though he didn’t realize it at the time, Aslan). Which means that, according to the “Deep Magic” of Narnia (a sort of contract set into the foundation of Narnia and its magic), Edmund’s blood rightfully belongs to Jadis. This is not because she is evil or the bad guy or anything like that, but because it is, in fact, her role in Narnia. She is, as Mr. Beaver calls her, “the Emperor’s hangman.” She brings death to traitors, and it is her right to do so. This is her right despite being an enemy of Aslan and Narnia (Lewis gives us a great deal more detail about what exactly was happening here when we get to The Magician’s Nephew, but I suspect he didn’t know those details yet as he wrote Wardrobe).

This may not sit right with you, and it didn’t with Lucy, either. She asks Aslan, “Can’t we do something about the Deep Magic? Isn’t there something you can work against it?”

Aslan is not pleased with the suggestion. The Deep Magic is written not only on the Stone Table, but also “written in letters deep as a spear is long on the trunk of the World Ash Tree.” These words are “engraved on the scepter of the Emperor-Beyond-The-Sea.” It’s the bedrock of Narnia, the words and decree of the Emperor, and Aslan is not willing to fight against his father’s magic or authority.

So although everyone wants Edmund released from the consequences of being a traitor, there’s no clear way to do it if Jadis remains unwilling. In fact, if they refuse to follow the Law of the Deep Magic, Jadis says, “all Narnia will be overturned and perish in fire and water.”

Aslan responds to this shocking detail by saying, “It is very true. I do not deny it.”

Edmund’s life is on one side of the scale, and Narnia’s existence on the other. Aslan seems to acknowledge that it is unjust in some sense (as he says to the Witch, “His offense was not against you.”). Aslan steps aside with Jadis to see if a deal can be brokered, and to the astonishment of all he returns and says, “She has renounced the claim on your brother’s blood.”

The children do not know, at that moment, how this has been accomplished. But very soon they learn that Aslan, the creator of Narnia, the son of the Emperor-Beyond-The-Sea, the Great Lion himself, had agreed to exchange his life for Edmund’s. Aslan would die to save Edmund, the traitor, and also to protect the people of Narnia from destruction.

Which brings us, at last, to the theories of atonement in Narnia.

Atonement is, very simply, the act that brings two parties into unity. It’s often talked about in the context of reparations for wrongs done: How is the one who has done wrong going to make things right so relationship can be restored? In Christian theology, the term atonement is used almost exclusively to refer to the process by which humanity and God are reconciled to one another. Atonement restores relationship and brings unity.

In Christian theology, the central moment of atonement (the crux, if you will) is Jesus’s death on the cross. And, believe it or not, theologians have been working hard to explain what exactly happened on the cross and why it matters ever since. I like to imagine a few satyrs and dryads sitting around smoking pipes and drinking dew and debating these same questions about Aslan and his death at the Stone Table.

There are many theories of atonement, as many as seven “major” theories and probably as many minor ones. I want to talk about three in particular in this article: penal substitutionary atonement, ransom theory, and Christus Victor. Remember, we are looking for Lewis’s answer to “Why did Aslan have to die?” with the understanding that the goal of Aslan’s death is to restore humanity (and fauns and giants and talking animals and such) into right relationship with God (or the Emperor-Beyond-The-Sea).

I: Penal substitutionary atonement

Let’s get this out of the way from the top: this is not Lewis’s answer. I want to include it, though, because if you are a part of Evangelicalism or have interacted with many Protestants, this is the most popular modern explanation for atonement and how it works, and it’s important for us to clear the deck here so we can clearly see what Lewis is saying about Aslan.

Penal substitutionary atonement says that God must punish (penalize) those who have sinned, and that rather than punishing the wicked, he allowed Jesus to be punished (substituted in the place of the sinner). This is most often formulated in a way that makes it clear that sin makes God angry, and so the “wrath of God” must be satisfied (we won’t get into this, but penal substitutionary atonement grows out of another theory called “satisfaction theory.”).

So, very simply: humanity sins. God is angry, and there must be a punishment for this sin. But Jesus intervenes and takes humanity’s punishment. Then, once the just punishment has been meted out, God’s wrath is sated and humanity can enter into relationship with God.

However, in Narnia it’s important to note this: The Emperor-Beyond-The-Sea is not angry at Edmund. Aslan is not angry at Edmund. Neither the Emperor nor his son are requiring this punishment (though the Deep Magic makes it clear it is not unjust for Edmund to receive this punishment). In fact, Jadis can “relinquish her claim” to Edmund’s blood should she choose. It is Jadis who wants to sacrifice Edmund at the Stone Table which is, as the dwarf says, “the proper place.”

Lewis was not a fan of penal substitutionary atonement as a theory. The most positive thing he wrote about it was in Mere Christianity when he said, “This theory does not seem to me quite so immoral and silly as it used to.” So I guess he was warming to it. Slightly.

To sum up: Aslan didn’t die in Edmund’s place to satisfy the wrath of the Emperor or to absorb divine justice.

II: The Ransom Theory

Again, simplified, the ransom theory says that humanity’s sin bound us to death and put us under Satan’s control. Satan held humanity captive. Jesus died to “pay the ransom” and free humanity from their bondage. In other words, the death of Jesus was payment to free human beings (in some formulations it is God who is paid the ransom, but in the more common and earliest forms the payment is made to Satan). Obviously, there are some pretty big parallels here.

Edmund is the Witch’s by right because of his treachery. His blood belongs to her.

Aslan buys Edmund back with his own blood. (Side note: this is the concept of “redemption” in action—Aslan redeems (buys back) Edmund.)

It makes sense that Lewis would like this theory, as it’s both one of the oldest explanations of the atonement, and was one of the most popular for at least a thousand years of church history. Note that Lewis names his Christ figure in the Space Trilogy “Ransom.”

III: Christus Victor

In Christus Victor (Latin for “Christ is victorious”) there is no payment to the adversary. Instead, the death of Jesus functions to work God’s victory over all the forces of evil. The cross is a sort of trick, a trap, that allows Jesus to show his power over death (via his resurrection) and utterly defeat evil powers in the world.

There are a lot of aspects of this viewpoint in the story of the Stone Table. The Witch had no idea there was a “deeper magic” that would allow Aslan to be resurrected (of course she didn’t or she wouldn’t have made the deal!). And once Aslan is resurrected (note the mice who chew the ropes that bind him—I have a fun literary reference to share with you about that a little further along, here) the Great Lion leads Susan and Lucy to the seat of the Witch’s power, where he breathes on the stone animals and beasts and creatures and they all come to life again. Then (after three heavy blows upon the castle door), they burst loose from there and Aslan leads all his newly reborn allies to defeat the witch and her monstrous crew that very day (or, as Aslan says, “before bed-time”).

Aslan explains it like this:

“though the Witch knew the Deep Magic, there is a magic deeper still which she did not know. Her knowledge goes back only to the dawn of Time. But if she could have looked a little further back, into the stillness and the darkness before Time dawned, she would have read a different incantation. She would have known that when a willing victim who had committed no treachery was killed in a traitor’s stead, the Table would crack and Death itself would start working backwards.”

In Christus Victor (or Aslanus Victor), the savior dies in the place of the sinner so that he can overcome his enemies and restore the whole world to its rightful state. As Aslan says before making his deal with Jadis, “All names will soon be restored to their proper owners.” Jadis will no longer be able to call herself “Queen of Narnia.”

Now it’s time for a fun aside from the sermons of St. Augustine (yes, we’re really throwing a party today!). In one of his sermons Augustine said, “The victory of our Lord Jesus Christ came when he rose, and ascended into heaven; then was fulfilled what you have heard when the Apocalypse was being read, ‘The Lion of the tribe of Judah has won the day’.” (When Augustine refers to “the Apocalypse” he’s talking about the book of Revelation in the Bible; specifically he’s quoting chapter five, verse five.) He then goes on to say, “The devil jumped for joy when Christ died; and by the very death of Christ the devil was overcome: he took, as it were, the bait in the mousetrap. He rejoiced at the death, thinking himself death’s commander. But that which caused his joy dangled the bait before him. The Lord’s cross was the devil’s mousetrap: the bait which caught him was the death of the Lord.”

So here’s a direct reference to the Lion who overcame his adversary by tricking his enemy into killing him on the cross, “the mousetrap” which was baited with his own death. Is this a little joke from Lewis, having the mice scramble out to gnaw away the cords which bound Aslan? I rather suspect it was.

At the end of the day, Lewis was a bit of a mystic when it came to questions of the atonement. In a letter in 1963, Lewis wrote, “I think the ideas of sacrifice, Ransom, Championship (over Death), Substitution, etc., are all images to suggest the reality (not otherwise comprehensible to us) of the Atonement. To fix on any one of them as if it contained and limited the truth like a scientific definition wd. in my opinion be a mistake.”

In Mere Christianity Lewis writes:

“A man can eat his dinner without understanding exactly how food nourishes him. A man can accept what Christ has done without knowing how it works: indeed, he certainly would not know how it works until he has accepted it. We are told that Christ was killed for us, that His death has washed out our sins, and that by dying He disabled death itself. That is the formula. That is Christianity. That is what has to be believed. Any theories we build up as to how Christ’s death did this are, in my view, quite secondary: mere plans or diagrams to be left alone if they do not help us, and, even if they do help us, not to be confused with the thing itself.”

I’ll close with this: More than once I’ve been in conversation about Narnia and someone has talked about “Aslan’s dirty trick” in hiding the deeper magic from Jadis. Or I’ve been in conversation about Christianity and someone has referred to some version of atonement theory as being morally reprehensible or not understandable.

When we feel that way, Lewis would encourage us to look for the myth which rings true to us. What part of the story catches our imagination and quickens our pulse? Is it the moment when Susan and Lucy play tag with the resurrected Aslan? The kind-hearted forgiveness Aslan offers to Edmund? The humiliation and eventual triumph of the Great Lion? You should press into that part of the myth and seek truth there.

As Lewis wrote, “Such is my own way of looking at what Christians call the Atonement. But remember this is only one more picture. Do not mistake it for the thing itself: and if it does not help you, drop it.”

Matt Mikalatos is the author of the YA fantasy The Crescent Stone. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.

Matt Mikalatos is the author of the YA fantasy The Crescent Stone. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.

I think Christus Victor is quite probably what Lewis was meaning. Moreover, it seems to be a prevailing factor in the Latin Church, to which Lewis’ friend Tolkien probably would espouse. Now (not sure before Vatican II), the Good Friday Liturgy always (no matter what year) Always, reads from the Gospel of St. John (no others). A Homilist once said that the reason we read the Passion according to St. John on Good Friday is because this Gospel is the one (unlike the other three Synoptics) which present Christ as already won. There is no defeated, dead Jesus in John, but a Victorious, Savior, King, especially prevalent in the opening ‘lines’ of Christ repeating several times “I Am” echoing Adonai’s words in the Burning Bush in Exodus. So, it’s an interesting thought to think about and an interesting point to mention when thinking about Lewis’s meaning of Aslan’s death.

I think I grew up with Christus Victor. “All names will soon be restored to their proper owners” also seems like a familiar sentiment. Though I’d be interested in knowing that the official positions of the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches are.

Although I do not believe, I prefer an order of things where death and sacrifice are a necessary part of the world (for renewal, for restoration, for growth) and not ordained by the will of a petty bully counting sins and demanding recompense.

@1 Those are all great points! Lewis went through a variety of feelings about the Roman Catholic church in particular. Obviously there were some Catholic men who were key in his conversion, but in later years he often complained about the “papists.” And Lewis couldn’t help but drift back toward medievalism on a lot of topics, so it’s no surprise that Christus Victor is one he has a particular affinity for!

@2 I think you and Lewis are of similar minds here!

Nice explanation. As an Anglican/Episcopalian layperson who is “into” theology, I enjoyed it very much.

I am surprised you didn’t mention René Girard, scapegoating, and the idea that since we are already forgiven/saved we are shown that the answer to bad violence is not “good” violence but rather that the wiling victim is resurrected showing that the violence was never necessary.

Why yes, my personal theology bends this way … ;)

@@.-@ Hey, I can’t cover everything! But I would love to hear more of your thoughts about what you love about Girard. How does that theology shape your personal practice?

I recall in the late 60s having the Silver Chair as the set book to be read aloud in class. To this day I recall the imigary. LWAW was a popular book and BBC show. Any Christian imigary was either lost to me or washed over in the shows. It was just a good yarn.

Years later I was most disappointed to find Lewis intended a Christian allegory. It almost spoiled reread enjoyment by classifying Narnia on the same boring and worthy shelf as Songs of Praise and Sunday evening TV.

But, probably like most of readers, I just ignored the idea and went back to enjoying the story and world.

While I consider myself pretty knowledgeable about Lewis, I have to say that this was the first time I had read this quote: ““I think the ideas of sacrifice, Ransom, Championship (over Death), Substitution, etc., are all images to suggest the reality (not otherwise comprehensible to us) of the Atonement. To fix on any one of them as if it contained and limited the truth like a scientific definition wd. in my opinion be a mistake.”

Now I’m wondering (and forgive me if this is already known and accepted as fact!) about Lewis as a Neoplatonist. It seems that this reference to “image,” along with the well-referenced idea of the “true myth” would speak to that kind of mystic understanding.

I don’t have a lot of firsthand experience outside of American evangelical Christianity (where I grew up and still reside), so I don’t know how well I can speak to other traditions. All three theories of atonement you discussed are certainly present in our hymnology, if not expressly in our theology. If pressed, I imagine that most would settle on penal substitutionary atonement. It seems to me that what Lewis is suggesting is that perhaps they are not entirely exclusionary. But I think that mystic Neoplatonism requires a certain comfort with knowing that there is the unknowable and accepting it (at least this side of the veil); I’m not entirely sure that American evangelicalism is on board with that idea.

Very interesting read. I agree that Christus Victor fits with the Deeper Magic aspect of Aslan’s atonement.

I think my personal beliefs lie somewhere between CV and PSA. The change I would make to PSA is not that God is angry over sin and is seeking punishment because of his anger, but that God is perfect and just and his nature cannot tolerate sin in his presence. So atonement isn’t required because of vengeance or spite, but because he requires nothing short of perfection. And so it’s through Jesus’ atonement that man is absolved of sin and able to claim perfection before God.

It’s been a while since I’ve actually read the book, but one thing that caught my attention while reading through the article was your statement “the central moment of atonement (the crux, if you will) is Jesus’s death on the cross.” It caught my eye because my church views the death as a necessary, but not the most important part of the Atonement. The suffering for the sins of the world and understanding of those sins and every other pain of all types. Then the resurrection, the fact that Christ lives, is more important to us than the fact that He died. That’s part of why (unlike most Christian churches) we don’t decorate with a cross.

But, more in focus with the article, I think that Christus Victor is probably the most in line with Lewis’s thinking because as you said, Edmund had already been forgiven, and the death wasn’t so much the focus as was Aslan’s triumphant return.

@6 Lewis would almost certainly encourage your reaction. He was a big believer in experiencing the story.

@7 Great observation! Lewis was heavily influenced by Neoplatonism starting with his relationship with Charles Williams. He found Williams extremely compelling, and there’s some indication that reading “In the Place of the Lion” (which is overtly Neoplatonist) is what pushed him into considering fiction as a more major part of what he wanted to try his hand at.

@8 I think that’s an increasingly common modern spin on the original PSA!

@9 I love that and it definitely fits better in some theories than others. But of course when “the gospel” is spelled out in many Christian texts it’s about Christ’s “death and resurrection”, so it’s wise to acknowledge both as part of the atoning work. But in many of the atonement theories it’s the death that effectively creates atonement, resurrection that shows God’s power over death and sin. I’d love to hear more about your church tradition, though. Would you mind terribly if I ask what denomination (if any) your church is in?

Ultimately the only reason Aslan has to do anything is that Lewis makes him. And while this is true in a sense of any fictional creation and their creator, it’s especially true in this case.

Because Aslan is meant to be the second person of the Trinity, he has to die – it’s a central aspect of the Christian faith. No matter whether you accept or reject any given explanation of Christianity’s doctrines, they remain. So the only real question is how Lewis chooses to present and justify the death. And he does so by citing ideas that have no correspondence with Christian beliefs, which is fine, but they’re entirely ad hoc.

I much prefer Diane Duane’s “Song of the Twelve” in Deep Wizardry, the ceremony the protagonists are taking part of and compare to a Passion play. The explanation given for why the Silent Lord arranges her own death actually makes perfect sense, which makes it preferable to either Aslan’s death or Christ’s crucifixion, particularly as there is no known rational explanation for the latter and it is considered a Mystery. (Emphasis on the capitalization.)

@10 Oh absolutely the death is an important facet of it, just not one that I dwell on as much, relatively speaking. Not at all! I’m a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (we’re often nicknamed Mormons haha) and I’m happy to answer questions! What do you want to know?

#5 – the key to me is how the scapegoat fits into both the scriptural history that Jesus would have known as well as putting forth a way to explain the idea that God has already forgiven everyone. Jesus did not come to change God’s mind about us – rather He came to change our understanding of God. The cross is not about an angry God taking out his rage on an innocent human. Rather the cross is about humans taking their rage out on an innocent god.

“He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

to walk humbly with your God?”

The second coming happens every time someone really opens their heart to God and begins to act accordingly – doing justice, loving kindness & mercy, walking humbly with God and loving your neighbor – all your neighbors – as you love yourself. That’s the real end of times for then you forget to worry about trying to get into heaven or evade hell and simply live the way you know, in your heart, that you should.

In Lewis’ tale, Aslan sacrifices himself even though it is unnecessary in end. He provides us with the perfect example of how to atone but is not, in the end, the actual atonement. Atonement is instead in our hands. Redemption comes at a cost that we must pay. We must atone for the evil we set loose in this world. To accept that forgiveness offered freely by the grace of God we must then accept responsibility for what we have done and actively work to make the world we have harmed better. Tikkun olam. Redemption is all about what you do with the forgiveness, the grace, you have been given. This is a never-ending process that begins with the moment of being born again and only ends when we leave this world.

That reminds me of John Barnes’ “Empty Sky”, where a magician from our world tricks an evil god in a magical realm into taking physical form so he can be permanently killed. The magicians travel back to our world and mention that the same thing happened here, two thousand years ago. Barnes says in the commentary that he had great difficulty selling that story.

‘So here’s a direct reference to the Lion who overcame his adversary by tricking his enemy into killing him on the cross, “the mousetrap” which was baited with his own death. Is this a little joke from Lewis, having the mice scramble out to gnaw away the cords which bound Aslan? I rather suspect it was.’

I guess it’s a possibility, but isn’t more likely that Lewis was just reffing an Aesop’s Fable – you know, the one about the lion and the mouse?

http://www.read.gov/aesop/007.html

@15 I also went to the lion and mouse fable. I guess both could be true, or neither, but I like both allusions.

Oh man, I have to admit I was a bit nervous about this one, since my first thought was, ‘but which version of Christianity’, lol.

In Catholicism, we call this whole topic ‘soteriology’ (the study of salvation) and like the Trinity, it’s something I won’t touch with a ten foot pole, lol. That said, my own limited understanding probably falls somewhere along the line of CV but I’m also quite happy to admit I don’t know *exactly* how it all works. I’m not even sure there’s an ‘official’ Catholic teaching on this topic because it’s one of those things that is basically a mystery and theologians have debated it endlessly. There are aspects of both Ransom theory and penal substitutionary theory that appeal to me, and also that do not appeal to me. Ransom theory sometimes appeals, but I also don’t love the idea that Satan really has any kind of claim at all. I kind of like what @8 says in a way – the big question in the whole first place is why any punishment/payment is needed at all.

Add into that, ideas about purgatory which, your discourse on Edmund being forgiven but there still being temporal consequences that must be washed away and dealt with. I know Protestants have a huge problem with purgatory as it is interpreted as a belief that the sacrifice on the cross wasn’t enough, although that’s not really how we see it.

I’m not sure that these are mutually exclusive, either in Narnia or in the real world. In my mind, Aslan’s death pays the ransom for Edmond, and his resurrection is what ultimately defeats the witch.

@12 Hello,

I know that your offer to answer any questions was addressed to the author of the post

but I wonder if you would mind giving a brief summary of the LDS Church’s understanding

of the Atonement?

I understand that Mormons (I trust that term is not offensive) do not accept the doctrines

of Original Sina nd the Fall of Man but rather take a view of sin and redemption that is more

akin to the Judaic view: we are accountable as individuals only for our own sinful acts and

redemption for these is obtained by contrition, repentance, and making restitution for their

consequences. What is the Mormon understanding of the role of Divine Grace and Christ’s

Sacrificial Atonement in this view if it is not to repair the wound caused by The Fall and the

consequent state of Man’s alienation from God?

@19

Sure thing!

(And no, the term isn’t offensive, just one that there’s currently a push to distance ourselves from, but that’s another topic entirely haha. If you want to hear more about that let me know.)

So we do most definitely acknowledge the Fall of Man, but we do view it as less of a problem than many Christian traditions. We believe that it was a vital step forward in our eternal progression, yes it was a transgression on Adam and Eve’s part, but also a necessary one. The Atonement’s immediate effect (for lack of a better term coming to mind right now) was to redeem all mankind from the Fall, all mankind will be resurrected because of the Atonement and receive a resurrected body. But that isn’t the end of the line so to speak, we believe that there are multiple Kingdoms in Heaven, also known sometimes of levels of glory and a few other names. These three Kingdoms are (from the highest to the lowest) the Celestial Kingdom, the Terrestrial Kingdom, and the Telestial Kingdom. The Atonement guarantees everyone a spot in the Telestial Kingdom, the lowest. The Atonement and His Grace also allows us to repent of our sins and participate in Saving Ordinances which make us clean enough to bear His and the Father’s Presence in the Celestial Kingdom, also known as Exaltation.

So I guess the short answer is that the Atonement and Christ’s Grace is the only way anyone will ever be reunited with our Heavenly Father and without it nothing we could do would do anything.

Sorry, I’m a little scatterbrained as I’m writing this (my baby boy was up a lot of the night) does that make sense? Please ask fro clarification where it doesn’t haha.

Links that probably explain better than I can:

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/bd/atonement?lang=eng

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics/atonement-of-jesus-christ?lang=eng

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/gs/atone-atonement?lang=eng

[Edit: Added a third link]

@12

Hello,

Many thanks for correcting my faulty understanding of Mormon doctrine and your (entirely lucid)

reply to my query.

I hope you get a good night’s sleep eventually!

My Gosh! What happened to Michael Byrd’s reply?

@21

Of course! Always happy to share! I’m glad that it made sense, and I hope I sleep sometime too haha!

@22

I think that it got eaten by a filter. I edited it to add a third link that I meant to put in originally, but after I hit update comment it disappeared. I’ve emailed the webmaster to see if I need to retype it or if it just needs to be approved somewhere by somebody haha.

@22, 23 — Yep, our spam filter gets a bit over-enthusiastic when there are multiple links in a post, but all should be well now.

Thanks Mod! That’s good to know haha!

@11 – It’s interesting that you cite Diane Duane in this context because she cites Lewis as an influence, if one she is alternately enamored and infuriated by. (She mines the spirituality tropes in her writing from a swath much larger than just “Christian” and the Powers of the YW verse tend toward syncretism.)

But to say Lewis’s ideas have no correspondence with Christian beliefs treats Christianity as a monolith, which it isn’t. From what I’m gathering from these articles and background knowledge, Lewis (who was a late convert) delved the breadth of Christian theology to settle on a personal interpretation that agreed with him, which he expressed through his work. You can argue how Christian they are or aren’t, but it’s incorrect to deny that there is argument.

Matt, thanks for the very helpful discussion of atonement theories in the Narnia context. Well done, and thanks.

@8, sounds like we’re in similar camps. I like Christus Victor, but I don’t think it captures enough of what’s going on to lean into it entirely. I also don’t think that Penal Substitutionary Atonement is fully sufficient. I tend to think more in terms of the Atonement being a kind of combination of CV and a Salvic Expression of Justice (SEJ? ;-D). In other words, God rightly demands moral perfection (i.e., holiness) from the universe He created (because it’s His universe); and the fact that it is fallen because of human sin means that a fundamental injustice has “broken” the universe. So when Jesus died on the Cross, in our place, for our sin, it was God showing that he did indeed have victory over sin and death, but also that in the death and resurrection of Jesus, He was willing to save us by creating justice on our behalf, and thereby fixing what went wrong in Eden.

Very well-written, insightful article about one of my most favorite series. Thank you.

The thing I’ve never understood is why some people say they are “disappointed” or feel “hoodwinked” when they find out it is a Christian allegory. I read that exact reaction from a very well-known author and I was so surprised. Lewis’ faith hasn’t changed the story. Lewis wasn’t tricking them. He never hid who he was. Can we only read books from authors who believe as we do? It’s no different from when a person comes out and says to those who struggle with it. “I’m still the same person I was before you knew. I haven’t changed.” The story has not changed because of who the author is. The things that made one love the story are still there. I am also shudder that one would say the cross was “a trick.” A rather painful, horrible thing to go through for a “trick.”

I guess it’s unlikely that a child would know that Lewis was also a theologian? And whereas I personally don’t have a problem with a writer being a believer (or how it might inform their work) in this instance, I think Lewis’s beliefs come in conflict with reader expectations in terms of genre – I mean, supposing every Nancy Drew book involved Nancy screwing up and her parents coming along and solving the mystery instead (as well as rescuing Nancy from whatever mess she had got herself into)?

Just wanted to come in and say that given Lewis’ background he was probably aware of the idea of how we fire the word atonement. The most common theory is the word was created by William Tyndale when translating the Bible into English. The Hebrew word he found in Yom Kippur and elsewhere had no direct English equivalent so he combined several words to convey the idea. At-one-ment was his solution for how God literally makes us one with Him again. In my view that would have more to do with Lewis’ concept than anything else, the very concept to big for the English language also being b other than all the theories of how it worked.

@26: Curiously, I have a similar relationship with Duane’s works.

The three theories of atonement listed are the ones I’m familiar with. I would love to know the names of the other four so I can look them up!

@13 re 5, yes, the humanity being wrathful to an innocent God thing is pretty much what I believe too. My understanding is that God incarnate acting through Jesus was intolerable to the powers of evil, large and small, and ultimately resulted in his death. It’s not that he had to die per se but hat God being God incarnate was going to be killed because of the way the world is. The resurrection is the more important part for me because it shows that God’s love is more powerful than evil or death. I like your ideas about Christ coming again through our actions too, though I do also believe in some sort of ultimate return and setting-right.

@26 re 11, Duane and I apparently feel very similarly about Lewis. I read a lot of his stuff young and it was formative for me, but as I’ve gotten older I’ve questioned some of it, and some parts are just intolerable while others are still extremely helpful. I just read Duane’s So You Want to Be a Wizard and there were three bits that seemed inspired by the Bible or by Christian (and maybe Jewish, I’m not sure) stories.

@34 Here’s a link to some of the more common/influential theories. There are a bunch more! And (probably closer to Lewis’s thoughts) there’s also the “multifaceted diamond” theory which is basically “Many or all of these show some important aspect of atonement and we can and should hold to many or all of them.” That has picked up a lot of steam in recent years (and historically it’s pretty common in different eras that more than one view was held simultaneously).

http://www.sdmorrison.org/7-theories-of-the-atonement-summarized/

@34 Thank you! Reading over these, I only really find Moral Influence, CV, and Satisfaction to be significantly different. The others all look to me like variations on Satisfaction. Which I guess is really to say that I find the core idea of Satisfaction untenable, so none of the tweaks make it work for me :-)

@35 So what’s interesting, kaci, is that “new versions” of the atonement theories are often responses to something that theologians found to be lacking in some previous version. So, for instance, “ransom” theory didn’t sit right with some because (in its original formulation) it appeared to be saying that “God owed Satan.” So from that comes the “satisfaction” theory that it’s about God’s justice, not Satan’s influence. So most of them have some connection to a previous theory and the shades of difference can be small. For instance, there are some who hold to “substitutionary atonement” but NOT “penal substitutionary atonement.” There’s a lot of fighting about it all. :)

And, as Lewis said, the most important thing is that at the end of the day the Christian teaching is that Christ’s death and resurrection is ultimately sufficient for humans to have relationship with God restored. How exactly that works is open for discussion.

@33: Do go on to read Deep Wizardry – I highly recommend all of Duane’s early works.

@37: That’s definitely the plan! Don’t know exactly when I’ll get to it since I somehow keep adding series!

I’m loving this series; thank you. I particularly loved this sentence: “I like to imagine a few satyrs and dryads sitting around smoking pipes and drinking dew and debating these same questions about Aslan and his death at the Stone Table.” It made me very happy.

Thank you so much! As a Christian, you’ve made me realize how thin my theological understanding is. I’d always somewhat taken the penal substitution theory for granted (though not without recognizing elements of what you’ve described in the other theories), perhaps mainly because its ideas are so wrapped up in many of the hymns.

@39 Ha! Thank you. I’m so glad. :)

@40 You are very welcome. Lewis often reminds us to be reading outside of our own theological traditions and eras, as it helps us to see our own particular blind spots. I’m glad you found the article helpful!

Lewis’s analogy to the nutrition of a meal falls flat for me. There are plenty of people who understand perfectly well how meals nourish them. It’s a knowable thing, whereas, he’s suggesting that the Atonement is unknowable. I’m not saying that Lewis is necessarily wrong about his conclusion, but how he gets there is fallacious reasoning.

@42 I always understood it as just saying that you didn’t have to understand how it worked in order for it to work. If you do know, that’s fine, but even if you don’t, you’ll still be nourished.

There are precious few things that require us to understand them for them to work. The issue isn’t whether we understand, but what the grounds are for concluding that it works. When it comes to the Resurrection, the only reason we have for thinking that it happened and changed the nature of humanity is the assertion of a religious doctrine. Lewis knew that wouldn’t work with Aslan in Narnia – children typically want to know the reasons for things, and few things annoy them like “Because”, so he had to come up with something. Hence the “Deeper Magic” bits. A Deus ex Machina is better than nothing at all.

@8: “…not that God is angry over sin and is seeking punishment because of his anger, but that God is perfect and just and his nature cannot tolerate sin in his presence. “

An important distinction, and very true. Remember, the definition of sin. The word literally means “missing the mark.” Sin is not the commission of evil. It is, rather, a failure to maintain the state of Grace that God gave us in creation. So Christ’s sacrifice, the washing away of sin, was not removing evil. It was *restoring* a state of grace; washing away not evil, but our imperfection.

Except that humans are hardly perfected. Or, if they are, they’re humanly indistinguishable from what they were before.

This is such a great discussion! I tend myself to be suspicious of dividing theologies of the Atonement up into clearly defined rival “theories.” In particular,. ransom is a subset of Christus Victor and early Christians had elements that sound like “penal substitution” to modern ears within a CV framework. Athanasius’ basic approach (and I think this is the one Lewis was most influenced by–he had read and written a preface for a translation of Athanasius’ On the Incarnation) is to say that humans deserve death because of sin and Jesus suffers death on our behalf, thus destroying the power of death and reconnecting humans to the divine life. Other theologians were much more explicit about death being personified as Satan and Jesus “tricking” or otherwise overcoming Satan.

As for the “wrath” language in penal substitution theology–pretty much all the classic theologians say that this isn’t literal emotional language applied to God, so I’m not sure that the “perfect justice” explanation is that different. The problem I myself have with penal substitution is the idea of God legally imputing our sins to Jesus and thus “pouring out his wrath” (whatever we mean by that) on Jesus as if Jesus were a sinner. Also the idea that God, rather than Satan, is the one from whom we need to be delivered. I think Lewis nicely captures a more truly orthodox approach by saying that the White Witch is the one demanding blood but the Emperor’s law undergirds her claim. (FWIW, I’m Catholic, from a Wesleyan evangelical background, and I grew up on the Narnia books and they deeply shaped my theology as well as my imagination, if the two can even be distinguished,)

More broadly, I’d say that treating the Atonement primarily as a legal problem raises impossible difficulties along the lines of “why would God set things up that way.” There has to be some “deeper” reason why that was the most fitting (Catholic theologians are historically wary to say “only” because that limits God) way for God to redeem us. I like the early Christian idea that God is fundamentally non-violent (though that may not fit Lewis too well) and so isn’t going to take us back from Satan through mere force. While the idea of God’s law giving Satan authority seems disturbing to a lot of folks, I think it’s preferable to the alternative of essentially turning God into Satan–i.e., into the one who directly demands and must be placated by death and punishment.

In a sermon I preached (as a lay Episcopalian, before I became Catholic) on Palm Sunday one year, I used the metaphor of shadow–that both Satan and the fallen earthly powers such as the Roman Empire exercise a kind of “shadow” of God’s justice, and Jesus submitted to that shadow in order to overcome it and reveal the true justice.

At the end most of us Christians would say it’s a mystery. But as my advisor in grad school (David Steinmetz, a historian of Biblical interpretation) used to say, the difference among theologians lies in _when_ we say that.

If anyone is familiar with the Nobilis role-playing game, the idea of the flower rite in that setting kind of makes sense to my idea of the meaning of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

@@@@@ 20 “We believe that it was a vital step forward in our eternal progression, yes it was a transgression on Adam and Eve’s part, but also a necessary one.”

I’m late to the party here, but I found this comment interesting because in the Catholic Church, one of the hymns for the Easter vigil says “Oh happy fault, oh necessary sin of Adam that won for us so great a redeemer.” I tend to interpret that partly as the Church burbling enthusiastically in the excess of her joy… but I think it’s also an expression of the idea that “God writes straight with crooked lines.” Or as St. Paul puts it, “where sin increased, grace abounded all the more” (Romans 6:20) and “in everything God works for good with those who love him” (Romans 8:28).

@49 I love the “God writes straight with crooked lines” idea! I think I first saw it quoted at the beginning of one one Andrew Greeley’s novels. When we get up to the Space Trilogy, Perelandra has some interesting things to say about falling and being redeemed vs. not falling.

I recently showed this article to a friend of mine who is a medievalist and she has been muttering about “anagogical mice” ever since.

I’ve just discovered and am reading these terrific posts now — so this is a very late comment.

Back in 1981, when I was finishing my dissertation on the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, which is mostly about the Harrowing of Hell, I wrote these verses to capture some of what it was saying. Some versions of the Gospel of Nicodemus did include the idea, not so much of a trick being played on the devil, but that the devil tricked himself by making assumptions. I suppose the poem may also reflect a childhood and young adulthood steeped in C.S. Lewis’s writings.

The Harrowing of Hell

We gained from Adam’s ancient loss,

Though Satan said “The gain is mine.”

He, greedy, plotted thorns and cross:

“The Man fears death—he’s not divine;

He dies; soon all will feel my sting!”

But then—the Light blinds hellish powers;

All Adam’s children are set free.

The third day dawns—the Ransom’s ours;

The Tree has given back the tree.

We are now children of the King:

He is our gain, and Satan’s loss.

Eve’s tree makes possible the Cross

By God’s great love: therefore we sing

Deo gratias.

I’d like to add to this, Jadis is not angry at Edmund. At least, not beyond her generally being angry at everything. She’s certainly not angry that Edmund betrayed his siblings and Aslan to, you know, her. All around, there’s really no one who’s angry at Edmund for what he did.

Really interesting read. I linked here from The Problem(s) of Susan, which is likewise engrossing, so I’m going to go finish that now.

I’ve just realized another mythological “borrowing” which I had missed so far – the similarity between Aslan’s death and Samson’s. Both get snared by a woman (Aslan willingly, Samson through his mistake); Both get bound and shaved, losing their power; both have their hair grow back and their power return, and both destroy their enemies.

I don’t think this parallel should be taken too far – Aslan is good and wise all through, and all his deeds – including letting himself be overpowered – are deliberate; Samson is a very chequered character morality-wise, and is snared by a woman he has an intimate relationship with (which he shouldn’t have had). But I do think C.S. Lewis took these elements from the Samson story.

This is far from my first time reading this thought-provoking article, but I just thought of something that supports the Christus Victor hypothesis: As you point out, Jadis is the Emperor’s hangman. She has a legitimate function in Narnia, bringing death to traitors.

Yet, at the end of the book, she’s dead. So who’s bringing death to traitors after that? There’s no indication that anyone has taken over her role in subsequent books. The implication is that it is now obsolete. There is no need for a hangman anymore, because Aslan’s victory over death completely changed the paradigm.