In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

In the 19th century, the pace of technological innovation increased significantly; in the 20th century, it exploded. Every decade brought new innovations. For example, my grandfather began his career as a lineman for American Telegraph in the 1890s (it was just “AT” then—the extra “&T” came later). In the early 20th century he went from city to city installing their first telephone switchboards. He ended his career at Bell Labs on Long Island, helping to build the first television sets, along with other electronic marvels. It seemed like wherever you turned , in those days, there was another inventor creating some new device that would transform your life. With the Tom Swift series, starting in 1910, Edward Stratemeyer created a fictional character that represented the spirit of this age of invention. That first series found Tom building or refining all manner of new devices, including vehicles that would take him to explore far-off lands.

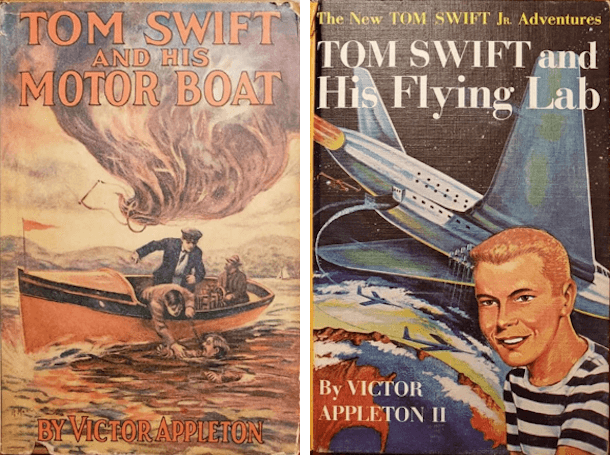

Tom Swift has appeared in six separate book series’ that span over a century, and in this week’s column, I’m going to look at three of them. Two I encountered in my youth: Tom Swift and His Motor Boat, which I inherited from my father, and Tom Swift and His Flying Lab, which was given to my older brother as a birthday gift. As an example of Tom’s later adventures, I’m also looking at Into the Abyss, the first book in the fifth series.

For many years the church I grew up in ran a charity auction, and every year, without fail, a number of Tom Swift books from the original series would be donated. They seemed to be tucked away somewhere in nearly every house in the neighborhood. That series had wide popularity (by some accounts, rivaling sales of the Bible for young boys), and opened many young minds to the worlds of science, creativity, and engineering. Many science fiction authors and scientists would later credit the series as inspiring them in their career choices. The science in the books was based on that known at the time, and many of the devices and inventions that Tom “created” in the books were eventually perfected by scientists and engineers in the real world. Jack Cover, inventor of the taser, has reportedly said that the device was inspired by Thomas Swift’s Electric Rifle, with an “A” added into the acronym to make it easier to pronounce.

The Tom Swift books appeared in several series’ over the years. The first series, published from 1910 to 1941, included 40 volumes. The second series, Tom Swift, Jr. (and attributed to Victor Appleton II), published from to 1954-1971, included 33 volumes. The third series, published from 1981 to 1984, numbered 11 volumes. The fourth series, published from 1991 to 1993, included 13 volumes. The fifth series, Tom Swift: Young Inventor, published from 2006 to 2007, spanned six volumes. The sixth and latest series, Tom Swift Inventors Academy, published starting in 2019, includes three volumes to date.

While there have been a few attempts to adapt the Tom Swift stories to other media, none have been successful, and only a short-lived TV show ever appeared. Interestingly, and possibly in tribute to the impression the books had made on a youthful George Lucas, an actor portraying Edward Stratemeyer made a guest appearance in an episode of the Young Indiana Jones television series, the plot of which involved Indy dating his daughter.

About the Author(s)

While all the Tom Swift adventures are attributed to “Victor Appleton,” (and the second series to “Victor Appleton II”) this is a house name used by the Stratemeyer Syndicate, the publisher of the books. Most of the first series was reportedly written by Howard Roger Garis (1873-1962), an author of many “work for hire” books that appeared under pseudonyms. Garis was known by the public primarily as the creator of the rabbit known as Uncle Wiggily.

I have previously reviewed other books issued by the Stratemeyer Syndicate, including two of the Don Sturdy adventures and one of the Great Marvel books, On a Torn-Away World. The Syndicate, in its heyday, was a major publisher of children’s books aimed at boys and girls of all ages. In addition to Tom Swift, Don Sturdy, and the Great Marvel Series, they included the eternally popular Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew mysteries, the adventures of the Bobbsey Twins, and a whole host of others.

As with many works that appeared in the early 20th century, a number of the earlier Tom Swift books can be found on Project Gutenberg.

Tom Swift and His Motor Boat

This is the second book in the original series, and while I could have read the first book, Tom Swift and His Motorcycle, on Project Gutenberg, I like the feel of a real book in my hands. And the book had the lovely musty scent of a book stored away for decades, a smell that brought me right back to my youth. The book, as all the books in the series do, provides a recap of the previous volume. And each book, in case it is the first Tom Swift story the young reader has encountered, reintroduces the characters and setting. I reacquainted myself with young Tom Swift, son of inventor Barton Swift, who lives in the town of Shopton, New York, on the shores of Lake Carlopa with his father, their housekeeper Mrs. Baggert, and the assistant engineer Garret Jackson (to the best of my knowledge, the absence of Tom’s mother is never explained). Tom’s particular chum is Ned Newton, who works at the local bank. He also frequently encounters the eccentric Wakefield Damon, who never opens his mouth without blessing something, for example, “Bless my overcoat.” Tom also must contend with local bully Andy Foger and his cowardly crony, Sam.

Unfortunately, as with many books of this period, there is some racism and sexism on display. Tom is friendly with the local “colored man,” Eradicate Sampson, and his mule Boomerang. Eradicate’s role in the stories is comic relief; he is frequently confused and amazed by Tom’s inventions, and speaks in thick vernacular studded with apostrophes. Tom does have a girlfriend, Mary Nestor, whose role in most stories is to require his help, as when her motorboat breaks down, because (in Tom’s words), “Girls don’t know much about machinery.”

This story involves Tom buying a motorboat that had been stolen and damaged by a local gang of thieves. Tom’s efforts to repair and enhance the boat, which he names the Arrow, are described in loving detail, and when I was young, these technical digressions made for some of my favorite parts of the books. While we take small internal combustion engines for granted these days, back in 1910 they were at the cutting edge of technology, transforming the way people worked and lived. Tom’s rival Andy, whose family has a good bit of money, is jealous of Tom, and he buys his own racing boat, the Red Streak. Their rivalry drives many of the adventures in the book. Also, unknown to Tom, the gang of thieves who had stolen the boat had hidden a stolen diamond aboard, a mystery that keeps the action going right up to the end. Once the villains are foiled, Tom rescues a balloonist who has dreams of building a new type of airship, and the book ends with the obligatory teaser for the next volume in the series, Tom Swift and His Airship.

As the series continues, Tom finds himself working on submarine boats, electric runabouts, wirelesses (radios), electric rifles, gliders, cameras, searchlights, cannons, photo telephones (television), and all sorts of other marvels. And he travels to caves of ice, cities of gold, tunnels, oil fields, and other lands of wonder. While the sheer quantity of his inventions push the bounds of implausibility, like many other readers, I always identified with Tom, and he felt very real to me.

I also remember that these books, which I read starting in the third grade, were the first stories I encountered that weren’t tailored to a specific age group, in terms of young readers. The author frequently used a lot of two-bit words, and this was giving me trouble, so my dad sat down with me one day and taught me how to sound out words from their letters, and how to figure out the meaning of a word from its context. After that, no book in our home intimidated me, and I entered into a whole new world as a reader.

Tom Swift and His Flying Lab

The premise of the second series is that it is written by the son of the original author, and features the adventures of the original Tom’s son, Tom Swift, Jr. By the end of the original series, Tom Senior had married his girlfriend, Mary, so it is entirely reasonable that, by the 1950s, they would have had a son. They still live in Shopton, but the Swifts now own Swift Enterprises, a large and vibrant company, presumably funded by patent income from all of Tom Senior’s inventions. They have a private airfield, and have enough money to fund construction of their own flying laboratory, so large that it can even carry smaller aircraft aboard. On the covers, Tom is portrayed as typical teenager of the era, with a blonde crewcut, striped shirt and blue jeans. Tom’s best friend is Bud Barclay, a test pilot. Eradicate Sampson’s role as comic relief has mercifully been replaced by a Texan cook nicknamed Chow, who also speaks in a thick vernacular that can be difficult for the reader to decipher. Chow also takes on some of the characteristics of old Wakefield Damon, peppering his speech with colorful phrases like “Brand my skillet.” Women still play a supporting role—Tom’s mother doesn’t get to do much beyond being concerned, while his sister Sandy often serves as the damsel requiring rescuing. Similarly, some of the portrayals of indigenous peoples in the book leave a lot to be desired.

This book features the titular flying laboratory, and in particular, detection devices that can find uranium deposits. The flying lab is propelled by atomic power, shielded by an improbable substance called “Tomasite plastic,” which provides better shielding than lead and concrete at a tiny fraction of the weight (thus getting around the issue that kept atomic power from taking flight in the real world). They plan to use the uranium detection device to locate deposits in a small South American nation, but run afoul of ruthless local revolutionaries, supported by sinister “Eurasian” agents who want those deposits for themselves. These villains use kidnapping, anti-aircraft missiles, and other despicable means in their efforts to steal the Swifts’ technological marvels and foil their efforts to find the deposits.

There is less interest in portraying realistic technology in this series, with Tom eventually taking off on outer space journeys, encountering aliens, and having other improbable adventures. As a teaser for these interplanetary adventures, a meteor falls on the Swifts’ property early in the book, and proves to be a manufactured object covered with hieroglyphics. As the books progress, the series begins to resemble the Stratemeyer Syndicate’s fanciful “Great Marvel Series,” rather than the more realistic original adventures of Tom Swift, Senior.

Into the Abyss

The later series’ books follow roughly the same format as the second series. In this installment from the fifth series, Tom is still the son of a famous inventor who heads a large company, Swift Enterprises, although he reads as a bit younger than the protagonists of the earlier stories. His best friend is still Bud Barclay, who is portrayed as a genius himself, although more oriented toward history and geography than science and technology. Representation of women and minorities has, as one would expect, significantly improved over time. Tom now has another friend, Yolanda Aponte, a girl from a Puerto Rican family. The female characters are more active, here—for example, when they need additional equipment during their adventures, Tom’s mother flies out to deliver it, and Tom’s little sister Sandy is presented as a mathematical prodigy in her own right.

In this adventure, Tom develops a carbon composite-reinforced diving suit that not only protects him from sharks, but allows him to dive to extreme depths (in fact, rather implausible depths, as even carbon fiber reinforcement would not permit some of his activities later in the book). And he also develops an electronic shark repellent device. His father is field testing a new deep-sea submersible, the Jules Verne-1, and plans to use it to deploy undersea seismic sensors along the East Coast to warn of tsunamis. He invites Tom, Bud, and Yolanda to come along on his research vessel. When Mr. Swift runs into trouble down below, Tom uses another of their submersible prototypes, along with his advanced diving suit, to save his father. While the tale is full of authentic details about deep sea operations and creatures, it also contains some uses of diving gas bottles, impromptu equipment repairs, and operations at extreme depths that undermined my suspension of disbelief. I found myself wishing the author had stuck a little more closely to representing real-world technologies.

The book is a quick and enjoyable read, and is specifically geared for younger readers, featuring a streamlined vocabulary and chatty, first-person narration.

Tom Swifties

The Tom Swift stories also gave birth to a type of punning joke that bear his name. In the original series, while people with questions “asked,” they almost never “said.” Instead, they “exclaimed,” “called,” “reasoned,” “muttered,” “replied,” “demanded,” “mused,” “cried,” et cetera; pretty much everything but “said.” And all sorts of adverbs were appended to that plethora of verbs. This literary tic, taken one step further with the addition of a punning adverb, became a type of joke, and here are a few examples I culled from the Internet (here, here, here, and here):

- “I can’t find the oranges,” said Tom fruitlessly.

- “I only have diamonds, clubs and spades,” said Tom heartlessly.

- “Pass me the shellfish,” said Tom crabbily.

- “I love hot dogs,” said Tom with relish.

- “I know who turned off the lights,” Tom hinted darkly.

My own introduction to Tom Swifties came from the jokes page in Boy’s Life Magazine, which often contained a few of them (and still does—I ran into a copy recently at my dentist’s office). In fact, thinking back, the whole genre of jokes now known as “dad jokes” probably came from exposing generations of young men to that magazine. They may not crack you up, but as every punster knows, evoking a groan can be just as satisfying as drawing a laugh…

Final Thoughts

He may not be as familiar to current readers as he once was, but in his day, Tom Swift was widely known, and his adventures were a huge influence on the field we now know as science fiction. Many of the writers of the Golden Age of the mid-20th century count Tom Swift as a favorite of their youth. And thousands of scientists and engineers (my father among them) had an early appetite for their professions whetted by the Tom Swift books.

And now it’s time to hear from you: What are your experiences with Tom Swift? Did you read the books yourself, or have you heard about the character secondhand? Which era/series of the books are you most familiar with? Have you shared any Tom Swift books with your children? And, if you are so moved, I would love to hear what you consider your favorite Tom Swifties!

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

Bizarrely, I think Tom Swift’s Flying Lab is the only one I’ve read — I have absolutely NO memory of the story but a keen sense-memory of pulling that particular cover off the family shelves!

I read Tom Swift and his Rocket Ship when I was in second grade and have loved them ever since. I’ve collected most of the Tom Swift Jr. books as a result. And now my son is reading them as well. Thank you so much for this review as it brings back a bunch of wonderful memories.

The two I recall having were Time Bomb, which was a Hardy Boys crossover, and Mind Games. Time Bomb was pretty good, basically a decent “fracture the timeline” dr who episode. Mind Games has imagery that stuck with me, very creative on the whole.

No idea how they’ve aged, or the general quality of the writing, as I don’t have them anymore, but they certainly stood out. The use of tech and really thinking it through was better than a lot of even decent Star Trek,

Did this series start the trend to give very short names to male heroes?

I remember reading a couple of these when I was very young. I don’t recall anything about the plots at this point, but I’m pretty sure there was a recurring villain called the Black Dragon. Does anyone know which Tom Swift series that would be, or am I crazy/mixed up with some different books?

When I was growing up, I spent my summers with my grandmother in Beulah, Michigan. My father’s nanny (who still lived with my grandparents) was also the town’s librarian, so I spent time in the library. One thing I did was to read every one of the Tom Swift books in the collection.

While I don’t remember the books, I do remember reading them.

I was a big fan of these as a young child in the mid to late 70’s–I think I must have found some of the second series, My other favorite at the time was Tom Corbett, Space Cadet which would have been of similar vintage, so I was apparently finding a bunch of older books though at present I have no idea how (apart from a memory of finding one as a display-enhancer at a furniture store and convincing them to sell it to me).

I remember at some point realizing that there had been an earlier series about Tom Swift Sr. and really wanting to find it, but having no way to do so.

I read the Tom Swift Jr series avidly at the golden age of sf (12) and a bit beyond. It was sad that they jumped the science-shark so badly, but at least they stopped to give an explanation of each law they were about to break before doing it. Those were often my first exposure to principles like the wave propagation square law, which shows how signals weaken over distance and was offset by Tom’s “Square wave inverter” (as I recall). At one point I had a nearly full set, except for some of the last ones published in the late 60s, which were as rare as they were separated from reality. Still, I’d loved them in their day.

A lesser-known series with a youthful protagonist who was more reasonably written was Rick Brandt, in many ways more of a proto-Johhny Quest (though from an earlier era) than Tom. Of the two, I’m pretty sure that Rick Brandt remains pretty readable, as it stuck to mysteries with a scientific backdrop and steered clear of science fantasy. I only had a few of the books, but it turns out that 11 of the original 24 books is available for a pittance in Kindle form as The Rick Brant Science-Adventure Series.

Black Dragon appeared in the fourth Tom Swift series (early 90s).

I read all but the last half dozen or so of the second series. I’d aged out of the series by the end. The “jump the shark” science didn’t help there. Despite that they were an important part of my reading when I was growing up and probably did play a major part in my becoming a scientist. “Tom Swift and His Repelatron Skyway” is the one that I still remember even after many decades. It was such a neat idea with lots of outside the (reality) box thinking to go with it.

@8 I had never heard of the Rick Brandt series, but it sounds like something I would have very much enjoyed reading in my youth.

I was a big Jonny Quest fan as a youth, and so was my wife. In fact, we just binge watched the entire original series on DVD a few weekends ago. Jonny was probably my favorite kid adventurer of all time.

Thanks for bringing this series from the Memory Vault, Alan. I also got started on reading science fiction with the second series – with the very first volume, in fact. At that age I was not a terribly critical reader when it came to style or characterisation but liked not being written down to, and even then I appreciated the forelock-tugging in the direction of scientific plausibility, not noticing that (as I recall) they tended to be delivered in the “As you know, Bob” format.

The Repellatron still bothers me, though. Even as a grade-schooler, I could see what a revolutionary device that was and what an industrial revolution it would initiate. But only Swift Enterprises seemed to exploit it and even then, mainly for the president’s son’s inventions and adventures. Also I was not, even then, really satisfied with the explanation of how it worked.

Greg Benford had a couple of his characters exchange Tom Swifties in one of the 1960s sections of his novel Timescapes. It stuck in my mind because this was the only time I’d ever encountered the expression.

I recall a Tom Swift with a rocket on the cover from my much older brothers’ bookshelf. I preferred the Hardy Boys, myself. The ridiculous use of dialogue tags like “demanded” and “mused” isn’t just from this series. I have to beat that particular problem out of new writing students all the time.

I grew up reading the Tom Swift Jr stories, not finding the earlier series until much later. I read and collected the whole series over the years of my childhood, with the books being the sure-fire birthday and Christmas presents my parents knew they could always fall back on.

Tom’s adventures fueled my very early interest in science and science fiction, leading me to Asimov, Heinlein and Clarke and beyond. I never quite gave up wanting to have my own self-named massive industrial empire that I could turn to building whatever new idea popped into my mind. (“Yeah, Jack… Do you think you could run up that new model of the Laser Multiassembler by Thursday?” “ No problem, boss!”)

I read some of the third series as a kid and recall enjoying them thoroughly. In this series, the invention aspect was not emphasized and they were straightforward science fiction adventure. According to my recollections, Tom Swift was the captain of a spaceship called the Exedra, crewed by his friends Ben Walking Eagle and Anita Thorwald (the latter of whom had a cybernetic leg) and their robot Aristotle. Despite the bombastic nature of the only title I can recall (Terror on the Moons of Jupiter), these books took themselves quite seriously and were not at all silly.

I read a large number of the Tom Swift Jr series in the very early 70s when I was in elementary school – the library had a good selection of them. It was clear even then to me that they were SF and not in any significant way reality-based. I’ve always had a fondness for them, and picked up a complete run a few years ago. I’m still working my way through them again.

For a similar vibe, try The Submarine Boys, originally published in 1909, by Victor Durham.

I encountered a handful of the Tom Swift Jr. stories when I was growing up, though at the time I bonded more strongly with the classic yellow-spine Nancy Drew and blue-spine Hardy Boys series. I do recall one of the things I liked about the Swift Jr. books was the poly-syllabic rhythm of the titles.

I didn’t connect well with any of Series I (too dated), Series III (too much of a jump ahead), or Series V (slanted too young). Series IV, now, the ’90s run…those were fun. Also, as it turned out, they were being written at least in part by experienced genre professionals — including Debra Doyle and James D. Macdonald, for instance. Others have mentioned the Black Dragon, a recurring nemesis who was actually fairly bright as evil geniuses go on this end of the literary spectrum. And if the science occasionally got a trifle exotic, in this series that usually meant that Tom himself was learning the rules as he went along.

I have not yet had a chance to look closely at Series VI, save to note that it seems to be aimed chiefly at middle grade readers (like Series V) and written in first person, both choices that seem to me out of touch with the character’s roots.

I’ll agree with those recommending the Rick Brant series (the comparison to Jonny Quest is well made); I’d also remind folks of the Danny Dunn adventures written by Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin, which I count as possibly the best-grounded contemporary kids’ SF of that entire period. There was also a short series about a little old lady named Miss Pickerell who got involved in straight-up scientific adventures, which I recall fondly.

But what you all need to know about the Tom Swift franchise is this:

The “classic” Tom Swift Jr. series is not nearly as dead as you think it is.

If you go prowl around on Amazon (or Barnes & Noble’s Web site), you will find that there are two or three authors who’ve each been self-publishing new stories in the “Swift Jr.” continuity for what looks like a couple of decades now. Thomas Hudson has more than a dozen further Swift Jr. adventures with properly polysyllabic titles, balanced between what look like fairly plausible inventions and situations straight out of Pulp Central. Added to this are several clusters of peripheral works, some featuring side protagonists, some that look like deliberate parody, and a number of works resurrecting other kids’ series heroes of the serial generation (Brains Benton, for instance).

Michael Wolff has what may be an even larger Swiftian catalogue (there’s an eight-volume subseries of Sandra Swift adventures), and I admit to actually buying Mary Swift and the Cossack Gold (featuring Mary Nestor Swift and Helen Newton, a number of years forward in the overall timeline, roving over more than half the globe hunting a treasure locked away by none other than Sherlock Holmes).

I have not the least idea why the trademark owners haven’t long since dropped an anvil on these authors — but to my considerable surprise, the Wolff book mentioned above turned out to be a perfectly credible modern thriller not too far distant in tone from Dorothy Gilman’s excellent “Mrs. Pollifax” spy adventures — with, mind you, the addition of a new (to me, not the Swifts) set of alien adversaries thrown in. Assuming that to be a representative sample, it might very well be worth taking a more thorough look at what Hudson and Wolff have been up to with the Swifts, the unauthorized nature of the material notwithstanding.

Eradicate Sampson’s role as comic relief has mercifully been replaced by a Texan cook nicknamed Chow, who also speaks in a thick vernacular that can be difficult for the reader to decipher.

I first read this and thought, “They replaced the black stereotype with a Chinese stereotype? How is that better?”

I was a big Tom Swift fan as a kid, but they haven’t stayed with me. I have very little recollection except for some of the titles. I’m not sure whether that says more about the series or more about me.

For a fascinating look at the operations of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, see “Ghost of the Hardy Boys” by Leslie McFarlane. McFarlane (1902-1977), was the first “Franklin W. Dixon” and wrote the first two-dozen Hardy Boys books. He describes how Stratemeyer pioneered the modern idea of “work for hire” publishing and pioneered the idea of “packaging” series for publishers. He also describes the rather fearsome “non-disclosure agreements” that promised terrible penalties if the ghostwriters ever revealed that they were behind the house names. He wrote that this even extended to timing authors’ meetings at the Stratemeyer offices so that no ghostwriter would ever encounter another ghostwriter on the premises.

I have never read any novels featuring Tom Swift, but any franchise featuring so many deliciously shameless puns can’t be ALL Bad! (-;

Tom Swift Jr. was more my speed when I was young, but I went back and sampled some original Tom Swift later on courtesty of UPenn’s On-line Book Page IIRC. I liked the semi-plausible technology of the early tales.

For a long time I thought that Tom Swift couldn’t be modernised, that the advent of computers and blockbox technology would mean that backyard engineering was no longer possible. But the Maker movement has turned me around on this somewhat over time.

Bought mostly by my father when he was young, my son now reads TS Jr (Series 2) frequently on his way to school as a 3rd grader. Three generations that learned chapter books with Tom.

And he’s made more than one “Flying Lab” including carried aircraft and vertical thrusters, from LEGO.

@13 The idea of a self-named massive industrial empire IS pretty cool, isn’t it?

@17 Thanks for that info. I was totally unfamiliar with series four, but if they had authors like Doyle and Macdonald involved, there must have been some good things going on. And thanks for the info on Tom Swift fiction written by other hands. I suspected the original series was beyond copyright protections, and like a lot of other famous characters, Tom Swift is now fair game for other authors to use. I would have thought that Tom Swift, Jr. would still be protected, though. If the copyright owners renewed their rights, books written in the 1950s should have retained their copyrights. But copyright and trademarks is a complex field I don’t even pretend to understand. Thanks for bringing up Danny Dunn; I didn’t read all of his adventures, but he was a fun character.

@18 The name Chow is the cook’s nickname, based on the fact he prepares meals, not Chow, the Chinese surname.

@23, 24 Great to hear that kids still cut their teeth on Tom’s adventures!

@25, I did figure out the “Chow” thing after I read your next sentence. I just thought it was funny how mental association worked for me–you had my brain on “racist stereotypes” so naturally that’s what came up as I read.

I had at least a couple of the 1970s paperback reissues, but never encountered any of the vintage books out in the wild.

@26 Our minds do tend to leap to conclusions. When I saw your comment, I was immediately concerned that I had been unclear. But all’s well that ends well. :-)

I started with Tom Swift Jr. in the early 60s. (About the same time I started buying the Ballantine paperback Tarzan series that were just being reissued.) When my family would travel to Nashville for my older brothers orthodontist appointments my Mother would buy me a book, always a TSJr. volume. I had a lot of them but I can’t recall if I had them all. I think they spanned about 3 feet on a bookshelf. Most had the yellow spines although a few had blue spines.

As a kid who already had determined to become an illustrator (not just an artist, an ILLUSTRATOR) I paid special attention to the cover paintings and interior illustrations in the TSJr. books. Bud was nearly always drawn with his mouth open yelling. One of the earliest drawings I can recall that I did was copying the cutaway illustration of some torpedo-like device Tom Jr. had invented (possibly something he would send to the earths core?).

I’ve thought about revisiting the series but that usually ends in disappointment, except with Tarzan – I can still re-read those.

Thanks Alan, for reminding me about an important early step on my road to becoming a voracious reader.

Based on the dates that you cite, I would have read the 2nd series, by Victor Appleton II. We bought a few of them before I segued into Heinlein juveniles, and I swear that I don’t remember them as having dust jackets. Nor did the Nancy Drew books, that I read at the same time (my parents being very progressive).

I read a number of the second series books when I was a little kid, at the same time I was into Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys, and The Bobbsey Twins. I always like the titles and the one I remember off the top of my head is Tom Swift and the Ultrasonic Cycloplane. I don’t remember much of the content but I remember enjoying it on the same level as Jonny Quest. The books were exciting and they only encouraged my interest in science and engineering, and when I got to school a decade or two later this girl majored in both of those things. I won’t say they’re the only thing that influenced me, far from it, but they certainly added to my enjoyment of them.