When I was in junior high, we were told to engage in a supposedly fun exercise relating to nuclear war. Each student was to imagine that they controlled access to a fallout shelter with room for a limited number of people on the eve of a nuclear war. Our assignment was to select who among us would be permitted access and who would be left outside to die. This taught important lessons: the authorities agreed that not all my classmates deserved to live (if not telling us which ones); also that while it is socially acceptable to let people die and decay, if you select them on the basis of who looks tastiest, somehow, you’ve crossed a line.1

Nevertheless, people absolutely love lifeboat stories like this. Inescapable crisis looms! Some will live! Some will die! Who will be saved? Consider these five classics.2

Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (1938 – present)

Superman’s origin story introduces a convenient way to sort people into survivors and the dead without forcing the protagonist into the ethically dubious position of being the one to choose. Brilliant scientist Jor-El foresees the planet Krypton’s imminent doom. Unfortunately for the people of Krypton, he is unable to convince that world’s government that the crisis is real or that steps must be taken to save the general population.3 At least in some versions of the story, he can’t flee himself, lest he provoke a general panic. In the end, he is able to save just one person: his infant son Kal-El, whom he dispatches to distant Earth.4 Too bad for the billions who die on Krypton, but hey, neither Jor-El nor Kal-El is responsible for the mass death.

***

“Breaking Strain” by Arthur C. Clarke (1949)

Struck by interplanetary debris in mid-voyage, the Star Queen loses most but not all of its life-sustaining oxygen. This places crewmen Grant and McNeil in an awkward position. The math is grim. The ship can support two men for twenty days. Star Queen’s destination is thirty days away. Under present circumstances, Star Queen will arrive at Venus bearing two corpses.

Twenty days of air for two men is another way of saying forty days of air for one man. But will one agree to sacrifice himself to save a fellow crewman of whom they are not particularly fond? Or will one or the other decide to murder their companion? If a decision is not made soon, both will die…

***

Day of the Triffids by John Wyndham (1951)

Bill Masen eludes the great disaster that descends on the majority of humanity thanks to dumb luck. His eyes bandaged after an operation, Masen had no way to watch the marvelous meteor showers that so impressed other people. Consequently, he was not struck sightless as was every human who watched the skies.

Managing a society in which the vast majority are blind is a tremendous challenge that Masen wastes very little time rejecting. He will not attempt to preserve the sightless majority. Better to flee to a remote location to wait out the inevitable deaths to come.

This strategy may not suffice. Mass blindness is only one element of the calamity. Once a convenient crop, the carnivorous triffid plants descend on an unprepared population. Escaping the blind is easy for Masen. Escaping voracious walking plants equipped with deadly stingers now swarming across Britain may prove impossible.

***

Plague Ship by Andre Norton (1956)

The Solar Queen’s adventures are plagued with misfortune, due to hostile fate or amoral business rivals. This time, soon after concluding a trading expedition to Sargol, the crew begins to fall victim to a mysterious malady. Is it poison? Is it some unknown parasite? A horridly contagious disease?

The Patrol believes that simple math dictates an obvious course of action. The Solar Queen’s problem might be the seeds of a deadly pandemic or it may not. Either way, dropping the space ship into a convenient star would render the question moot. Better for a handful of traders to die than to risk the deaths of billions. It is the logic of the lifeboat, reversed.

Inexplicably, the crew of the Solar Queen are not swayed by such logic. They’re determined to survive both disease and Patrol.

We know they will (thanks to plot and series immunity)…but how?

***

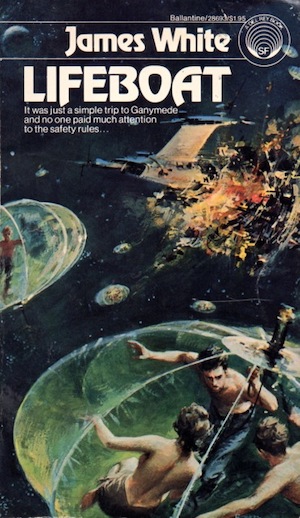

Lifeboat by James White (1972)

Interplanetary travel is routine, almost boring. Certainly nothing serious could go wrong in this, a novel named after the emergency vessel to which one flees following disaster. Eurydice proves fantastically unlucky; a reactor mishap forces the survivors to flee the doomed ship. Now occupying a cloud of lifepods, the passengers and crew are offered the opportunity to discover which will disappoint them sooner: the technology on which their lives depend, or the assortment of strangers from whom the pods offer no escape?

***

Furious rebuttals? Further suggestions? The comments await.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]Oddly, the same junior high school forbade me to give a speech about nuclear war, one that I made really personal and relatable by calculating the effects of a nuclear blast for a representative sampling of my classmates, based on the distance from ground zero of their homes.

[2]I am shocked and outraged at the cynical suggestion that this essay focuses on older examples merely to provide a pretext for a follow-up detailing some modern works [typing furiously]...

[3]One of the hazards of helming long-running series is that later revelations can cast early decisions into an unfavourable light. 1961’s Adventure Comics #283 revealed that Krypton had the means to project people into the Phantom Zone, where they were intangible and immortal. For the most part this method was used to punish the worst criminals, although on one occasion it was used as an emergency medical treatment. Still, it raises the question of why Jor-El didn’t dispatch people en masse to the Phantom Zone, technically not violating the guidelines imposed on him, for later retrieval. The Watsonian answer is Kryptonians took a very dim view of being sent to the Zone; they may well have preferred death to eternal limbo. The Doylist answer is that there was no way for a character in a 1938 story to take advantage of something not introduced into continuity almost a quarter century later. (The difference between Watsonian and Doylist approaches can be found here: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/WatsonianVersusDoylist)

[4]As the Superman continuity developed, more and more Kryptonian survivors turned up, leaving one with the impression that the only people who actually died on Krypton were Superman’s birth parents.