In this scattershot series, we’ll be delving “too greedily and too deep,” prying gems out of the glorious rough that is the extended legendarium of Tolkien’s world. This includes drawing on The Lord of the Rings itself, The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, and the History of Middle-earth (or HoME) books.

Orcs, amirite? The shock troops of the Dark Lord’s armies. The rank-and-file of the bad guys in Middle-earth. Called a “hideous race” bred in “envy and mockery of the Elves.” Everyone’s got feelings about them. Feelings… and differing facts, maybe.

It should be understood that in J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium, the nature of Orcs—the spirit and agency of the Orcs—is not consistent all throughout. Were they really Elves once? Are they soulless constructs of evil and therefore irredeemable? Or can they be reformed, if not in life then at least in death? The answer will always depend on where you’re looking or which incarnation of Tolkien’s ideas you prefer. We as readers get to decide which version of Orcs we will imagine, but none of us gets to decide what others choose (nor decide what Tolkien must have “meant” with them beyond what he wrote). If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice. Take them case by case or book by book. Or orc by orc.

I’m going to tackle this subject in at least two installments. This article looks at Orcs in Tolkien’s best known books, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Next time, I’ll look further back, and further in, to his larger legendarium via The Silmarillion and the History of Middle-earth series.

I also want to be clear about something. This isn’t a treatise on the origin of orcs as a concept, which Tolkien borrowed, at least in part, from Beowulf and/or the Old English word for ‘demon.’ The idea of a monster-people that epic heroes have to fight predates his works, but I think it’s safe to say that Tolkien was the one to popularize them in modern literature.

Buy the Book

The Witness for the Dead

Even more important: After this introductory segment, this article is certainly not going to be a discussion of how orcs are portrayed elsewhere in fantasy fiction; that is, where others have taken them. I for one am all for variety. The more reimagined orcs are, the more diffused the concept, the less they have to do with Tolkien—whether they are made good, evil, or wholly independent. Most of the time authors have normalized orcs as the bad guys, but not always. It’s been changing. There are now scads of different versions in fantasy media and games. For example, I understand that the green-skinned Orks of Warhammer 40k are biologically engineered creatures that grow from subterranean fungus. (Which I think sounds actually pretty cool.)

The earliest Dungeons & Dragons orcs (always lowercased, by the way) were quite derivative of Tolkien, and there was nothing redeeming about them. As presented in the 1977 Monster Manual, they are slavers and bullies who “dwell in places where sunlight is dim or non-existent, for they hate the light”; they “are cruel and hate living things in general, but they particularly hate elves and will always attack them.” They had a decidedly porcine appearance, though (which isn’t Tolkienesque).

Flash forward to a depiction I’m very fond of: the orcs of Eberron, a high adventure D&D world of pulp noir and complex political themes that debuted in 2004. There, millennia in the past, orcs used druidic magic to repell and imprison extraplanar (alien) invaders, thereby saving the world, and this was long before humans bulldozed their way onto the scene. In the present day, those orcs’ descendants enjoy proper citizenship in sovereign nations and are respected for their strengths and talents. There’s even a dragonmarked house with blended orc and human blood: House Tharashk! (These houses are D&D’s answer to the megacorp, which can be either powerful and creepy or totally benevolent, depending on the DM’s needs.) Bottom line: Eberron’s orcs and half-orcs are burdened no more by racism than are their human counterparts.

Just look at these half-orc prospectors on a dragonshard dig. They look so happy.

I did have the good fortune to invent a half-orc character in my Eberron novel, The Darkwood Mask: She runs a detective agency in Sharn, the City of Towers, and is my protagonist’s mentor. She’s got portraits of her nieces and nephews on her office wall. And so Thuranne Velderan d’Tharashk is nothing at all like the orcs and half-orcs of Middle-earth. Given the demeanor of Saruman’s minions, for example, the Uruk captain named Uglúk—who oversees the capture of Pippin and Merry—probably never had his portrait hanging on the walls of his aunt’s lair in Isengard. He might have stuck a blade in her back, though. Point being, Tolkien’s Orcs are Tolkien’s Orcs, and if you want to gripe about how orcs have been used by other writers after him, it’s best to take it outside…Arda.

In any case, Orcs aren’t just a Third Age scourge. Tolkien’s writings after The Lord of the Rings give us a lot more information about them and their origins in the Elder Days of Middle-earth. And like a lot of his world-building, those writings spin off to different places as he wrestled with his own thoughts. Ultimately, the true nature of Orcs remains inconclusive. Remember that The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and the entirety of the History of Middle-earth series was published after Tolkien’s death by his son Christopher, who took on the task of sorting, interpreting, and curating a ridiculous amount of notes, essays, and stories.

So we have to go into this knowing that there’s no hard answer. But that doesn’t mean we can’t explore the theories about Orcdom and consider Tolkien’s words about them even outside the text. Having said that, let’s start with the most familiar holes in the ground.

The Hobbit

In 1937, they are merely goblins, presented side by side with dragons, giants, “and the rescuing of princesses and the unexpected luck of widows’ sons,” all features of the fantastical tales allegedly told by Gandalf at Hobbit parties. Later, Bilbo meets some very real goblins in the Misty Mountains and spends a lot of time running away from them. The word “orc” only comes up once, referring to “bigger” goblins who stoop low to the ground even while running (and can therefore navigate narrow tunnels). Yet we do get the sword Orcrist, which of course means “Goblin-cleaver.”

Gandalf later warns Thorin and Co. to not bother going around Mirkwood the northern long way, because the Grey Mountains up there are “simply stiff with goblins, hobgoblins, and orcs.” Perhaps owing to its fairy tale foundations, the goblins of this book are simplistic foes. They are uniformly wicked, and we don’t learn enough about them to even ponder the plausibility of goblin reform. They trouble Bilbo and his friends both inside and outside the proverbial frying pan, then contend with everyone else in the Battle of the Five Armies. Of the one present goblin given a name—Bolg, their leader—we’re given no particular insight. In fact, Tolkien connects Bolg to Azog, the goblin who killed Thorin’s grandfather, only in a footnote. (We do get the name of another past goblin king: Golfimbul, whose decapitated head led to the game of golf!)

Tolkien admitted taking inspiration from the stories of Scottish writer/poet/minister George MacDonald (1824–1905), “except for the soft feet which I never believed in.” In The Princess and the Goblin, goblins’ feet are their weakness. However, in The Hobbit, it’s the sun that goblins cower from, and that, too, sets them well apart from even dwarves, for “it makes their legs wobble and their heads giddy.” Dwarves might live underground like they do, but they’ve got no problem with daylight.

Ultimately, goblins occupy a place in the story as they often did in fairy tales, as bogeymen who trouble everyone they meet.

Goblins do not usually venture very far from their mountains, unless they are driven out and are looking for new homes, or are marching to war… But in those days they sometimes used to go on raids, especially to get food or slaves to work for them.

Beyond this, the only bit of nuance and a look at their larger impact on the big picture is this passage, which includes some of the narrator’s own speculation:

It is not unlikely that they invented some of the machines that have since troubled the world, especially the ingenious devices for killing larger numbers of people at once, for wheels and engines and explosions always delighted them, and also not working with their own hands more than they could help; but in those days and those wild parts they had not advanced (as it is called) so far.

They are credited with mining and tunneling at least “as well as any but the most skilled dwarves,” yet we’re also told goblins much prefer to get prisoners and slaves to do their work for them. As with the makers of bombs, I have always equated this with Tolkien’s contempt for real-world slavers.

The Lord of the Rings

In 1954, Tolkien flips his words around and goes with orc more frequently than goblin. The words are used fairly interchangeably, and refer to the same species—if “species” is the right word (it probably isn’t). Throughout The Lord of the Rings, Orcs are unquestionably evil in nature. To be fair, we’re never inside their heads and never get an Orc’s actual point of view. As to how they’re regarded among the Wise or even the vastly experienced, we can look at Aragorn’s words to Sam in Fellowship. In the chapter “Lothlórien,” the ranger’s just stopped the company to assess their wounds following their flight out of Moria.

‘Good luck, Sam!’ he said. ‘Many have received worse than this in payment for the slaying of their first orc.’

A dehumanizing thing to say of Orcs, maybe—like they’re sport, not people, less than human. But then Orcs aren’t human. Or were they in the distant past? It’s one theory Tolkien mulls over in post-Rings compositions, and I’ll talk about that another time. But they’re barely subhuman as presented through most of this book. And Aragorn should know; he’s a Dúnedan and surely one of the best-traveled of Men.

In “The Tower of Cirith Ungol,” Sam wonders if Orcs take poison and foul air as sustenance. Frodo answers:

‘No, they eat and drink, Sam. The Shadow that bred them can only mock, it cannot make: not real new things of its own. I don’t think it gave life to the orcs, it only ruined them and twisted them; and if they are to live at all, they have to live like other living creatures.’

There is only a brief rumor in The Lord of the Rings of Orcs having been Elves originally—for that “fact” we must wait for The Silmarillion—but it’s at least understood that Orcs, if they are living creatures and not mere constructs of evil, were fashioned to be the way they are from…something else once. Gamling of Rohan calls Saruman’s breeds “half-orcs and goblin-men,” so there it seems there is some human stock among the Isengard breeds. An unpleasant but thankfully unexplored fact.

After the Battle of the Hornburg, Théoden spares the lives of all the “hillmen”—that is, the Dunlendings whose “old hatred” Saruman had inflamed and manipulated to join his armies—but no mercy is given to Orcs. Then again, the surviving Orcs from Helm’s Deep are slain by Ents and/or Huorns, not by Men, after they flee into the forest.

Yet after the Battle of the Morannon (the Black Gate) and the final overthrow of Sauron, Orcs are scattered and presumably hunted and destroyed whenever they are found. The Easterlings and the Haradrim, in contrast, are pardoned by King Elessar and no vengeance is pursued against them. We don’t get more—oh, how I wish we got more!—about Aragorn’s past adventures “far into the East and deep into the South, exploring the hearts of Men.” I have to assume that, of all the Men of the North, he’s among the most informed and enlightened. The armies from the South and East that join Mordor in the war are only that: the armies that came. We are not told that all the warriors of Harad and Rhûn departed their lands or that they didn’t don’t have their own struggles against Sauron’s influence. We’re not given much to go on, ultimately.

Back to my point: nowhere do we see Orcs spared, nor the whisper of a clue that they’d even seek parley or pardon. That would be a gamechanger, I think. Yet all evidence depicts them as creatures of strife and cruelty.

Which is not to say that they don’t sometimes sound a lot like ill-tempered humans in real life grumbling about their jobs and their orders. In the chapter “The Uruk-hai,” we see firsthand that differing allegiances exist among Orcs. Pippin listens to the squabbles of his captors: Orcs of Mordor, Uruks of Isengard, and some Northern goblins from Moria. We see the obvious contempt they hold for one another, no less than for their enemies. Uglúk serves the White Hand, while Grishnákh is loyal to the Great Eye. Both have their orders, and some heads are swept off in the dispute about where to take their prisoners.

Much later, we get still more insight into Orc personalities in The Return of the King, when Sam eavesdrops on some soldiers on the road. These only serve the Great Eye, because of course now we’re among Mordor’s occupants. First we’ve got Shagrat and Gorbag on the approach to the Tower of Cirith Ungol. They call each other lazy—verbally abusing your coworkers just seems to be Orc Civility 101—each implying the other is avoiding war. You know, the thing that most of the time we’re led to believe is their favorite hobby.

‘Hola! Gorbag! What are you doing up here? Had enough of war already?’

‘Orders, you lubber. And what are you doing, Shagrat? Tired of lurking up there? Thinking of coming down to fight?’

Notice that going off to kill enemies seems as least as desirable to them as staying home. Orcs could happily fight or not fight for hours! Calling out others for shirking one’s duty is a real thing for Orcs, isn’t it? But isn’t it common, especially among ne’er-do-wells, to accuse others of one’s own crimes? Well, in the tower itself, Sam hears these same two Orcs badmouthing not only their comrades but their non-orc superiors—like the Nazgûl, who give Gorbag “the creeps.” They’re paranoid, they’re afraid of being ratted out, and they sure like to throw shade. What else do they like? Oh, yes, defecting again. Shagrat and Gorbag have big dreams if the war wraps up in their favor:

‘But anyway, if it does go well, there should be a lot more room. What d’you say? – if we get a chance, you and me’ll slip off and set up somewhere on our own with a few trusty lads, somewhere where there’s good loot nice and handy, and no big bosses.’

‘Ah!’ said Shagrat. ‘Like old times.’

Later still, Sam and Frodo catch some conversation between two different Orcs in “The Land of Shadow.” One is a small tracker with “wide and snuffling nostrils,” seemingly bred for smelling things; the other is a large, well-armed soldier. Aside from insulting one another, the Orcs speculate and grumble about the war (per usual). When the tracker starts spouting “cursed rebel-talk,” he gets threatened by the fighting-orc. He doesn’t let up, even remarking with glee about the demise of the Witch-king (“They’ve done in Number One, I’ve heard, and I hope it’s true!”), so they turn on each other. It doesn’t take much to get Orcs infighting—something our heroes take advantage of several times throughout the book.

Obviously, Orcs are not considered to be part of the Free Peoples—that is, folk who are not under Sauron’s dominion. Independence isn’t even an option for them, even though there was once a huge period of downtime for them. Until Sauron’s final defeat in the year 3019 of the Third Age, there was never a time when at least one Dark Lord wasn’t lurking somewhere on Middle-earth. Since the time of their creation, of their original corruption and breeding, Orcs have always had a master somewhere, even when they don’t know it.

So with that in mind, let’s go back to the beginning, and to Frodo. He is arguably the most outward-facing hobbit of the Shire, gathering what news he can of the outside world. He actually gets most of it from traveling Dwarves. In “The Shadow of the Past,” he learns (and therefore we learn) that the Dark Tower (Barad-dûr) was rebuilt and…

Orcs were multiplying again in the mountains. Trolls were abroad, no longer dull-witted, but cunning and armed with dreadful weapons.

This implies that before Sauron’s return the Orcs weren’t multiplying so much. It’s easy to overlook this fact, as readers. Easy to assume that Orcs have always just been an ongoing problem for everyone all the time. But they haven’t been. They’re not natural denizens of the world who expand and colonize and erect sprawling kingdoms of their own. In the Third Age, they only venture out when the Shadow is returning, even though violence seems to be baked into them.

But wait! Aren’t we told that Aragorn’s dad was slain by Orcs when he was a baby? (And, like, with an arrow in the eye?!) And wasn’t Elrond’s wife tormented by Orcs after getting captured in the Redhorn Pass? What about the Orcs that left the Misty Mountains in The Hobbit, and before that the Orcs that war with Dwarves in Moria? Yes, all true…but all of that comes quite late in the Third Age, relatively speaking. And it’s directly linked to Sauron’s big (and sneaky) comeback.

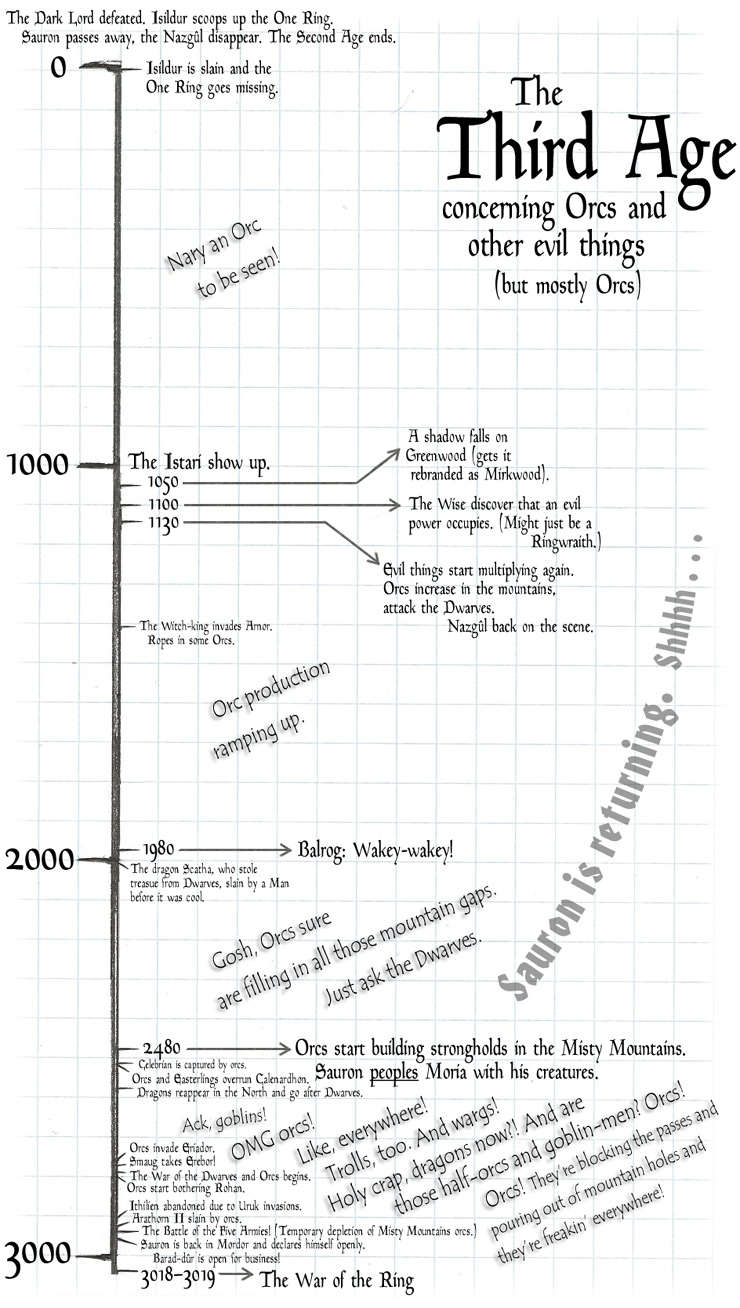

The Appendices of The Lord of the Rings

The textual evidence is that for the better part of two and a half thousand years, Orcs and trolls and other evil monsters weren’t a great nuisance in Middle-earth because the Dark Lord was too weak to stoke them to action. After Sauron is defeated by Elendil and Gil-galad at the tail end of the Second Age, the Dark Lord “passes away.” On top of this apparent demise, Isildur robs him of his trusty Ring, so he’s diminished, impotent, and all but gone for a long time. The good guys actually think he’s donezo. Finis. Caput. An ex–Dark Lord.

Obviously, things don’t just get peachy for Middle-earth in those years of his absence, but my point is that it’s not monsters who are the problem. Mordor’s Orcs were pretty much wiped out by the Last Alliance, so it seems all that remains of them are scattered bands and little mountain-dwelling pockets.

So why, as the Third Age proceeds, does the kingdom of Arnor fracture and fade, why does Gondor itself peak and then decline, and why do the Elf-realms shrink and become estranged from Men? Because the legacy of the Dark Lord(s) continues, even without Sauron’s direct oversight. Easterlings under his influence invade, as do Haradrim and the Corsairs of Umbar—both, incidentally, led by the Black Númenóreans (the crueler coastal descendants of Númenor). Even the Nazgûl eventually return before their master can take full shape again. The Witch-king and his kingdom of Angmar arise. It’s all enough to disquiet Middle-earth for a very long time, yet it’s all essentially Men fighting Men (be they living or dark undead).

More than a thousand years after Sauron’s defeat, a bit of orc-mojo returns. From the Tale of Years (Appendix B), we get:

c. 1130 Evil things begin to multiply again. Orcs increase in the Misty Mountains and attack the Dwarves. The Nazgûl reappear.

For a sense of scale, 1130 is about eighteen hundred years before Gandalf gets “good-morninged by Belladonna Took’s son” as if he were a door-to-door button salesman.

And by the way, that term, “evil things”…it never refers to Men or Elves or Dwarves of any stripe. Not even Men who fight under the banner of Mordor are ever called that. It’s a term reserved only for unnatural monsters or spirits of the dead, those either bred or corrupted in some fashion by great powers of evil like Sauron or Morgoth. We’re talking goblins, Orcs, trolls, Wargs, Barrow-wights, giant spiders, dragons, and assorted fell beasts. Balrogs and mysterious abominations like the Watcher in the Water are not even Sauron’s work; they were either bred or became corrupted each in their own time in ancient days. Balrogs, as all Silmarillion readers know, are Maiar spirits that fell to the service of the first Dark Lord in the earliest of days.

So am I saying that in all these centuries before the year 1130, there aren’t any Orcs bothering anyone? Really, not even just one or two Orc-randos chasing some folks around with pointed sticks? Not precisely, but Orcs just aren’t numerous or organized enough to make the top ten list of Things Troubling the Realms of Men during that time. There is no record of them harassing anyone outside of the mountains until after 1300. That’s when the Witch-king founds Angmar (circa 1300), and then starts invading lands of the North. We’re told that he fills out his army of evil Men with Orcs and other fell creatures.

Now, when the Orcs do get that bump in their population, they go after Dwarves because…well, they’re mountain neighbors and those First and Second Age grudges aren’t going to nurse themselves. Now, quite unlike the Easterlings and Haradrim invaders, Orcs hate the sun, so they remain holed up even when they’ve started to increase their numbers. But notice that when Orcs do start to multiply (around 1130, as cited above), it’s not just out of left field. It’s important to see that Orc-baby boom comes after these two entries from a bit earlier in the Tale of Years:

1050 Hyarmendacil conquers the Harad. Gondor reaches the height of its power. About this time a shadow falls on Greenwood, and men begin to call it Mirkwood.

c. 1100 The Wise (the Istari and the chief Eldar) discover that an evil power has made a stronghold at Dol Guldur. It is thought to be one of the Nazgûl.

Except we know it ain’t no Ringwraith: it’s Sauron himself, and it is his clandestine return that rekindles the fires of Orc propagation. And though they may be skirmishing with Dwarves in mountainous halls, Orcs still remain on the down-low for another millennium and then some. That’s a whole lot of time.

So why am I distancing Orcs from center stage so much? Because unlike the other other races of Middle-earth, their population, their reach, and even their malice are intrinsically linked to Sauron. They may reproduce like other living things, but even then, not in significant numbers without the Shadow’s influence. They don’t put in the work of attacking Men and Elves unless they’re (effectively speaking) under orders to do so. Men and Elves take an awful lot of hard work to go up against. So do Dwarves, but at least there’s no need to go marching under the sun to get at them.

We can accuse the good guys in The Lord of the Rings of racism against Orcs (if we want), but even the “evil Men”—those manipulated by Sauron—are not objectively demonic in nature. Not even close. Misguided Men can be reasoned with, and are. When they are denied their generals and the spiritual might of their allies, they surrender. Orcs, however, never seek absolution. And yet…Orcs are a sort of watered-down evil, aren’t they? Engines revved, they’re ready to race, but they’re only at their worst when their boss is at the wheel. When their boss is taking lunch in the back seat, or not even in the danged car, they power down, becoming idle. Something to think about—we’ll get more about this in the next installment of this topic.

But back to “evil things” in the Third Age: Though the Dwarves of the Misty Mountains do have Orc issues from time to time, the kingdom of Khazad-dûm (Moria) has stayed secure all these millennia—since the First Age. They’ve dealt with Orcs since forever, surely they can hold up indefinitely. But then, almost nine hundred years after that “Evil things begin to multiply again” mark, we come inevitably to the year 1980, when all that deep delving in search of mithril finally backfires.

“Oh yeahhhhh!” says the Kool-Aid® Man Balrog.

Appendix A reminds us, on the subject of the Balrog, that all “evil things were stirring,” so there may be a correlation between the waking of this Nameless Terror and the Dark Lord’s proximity in western Mirkwood. In true Tolkien fashion, a tiny footnote is all we get about something that could have been rich with more exploration. Referring to the Balrog’s beauty sleep that the Dwarves interrupt, we’re told that it might have been “released from prison; it may well be that it had already been awakened by the malice of Sauron.”

Cool, cool. So Sauron does get a dash of credit for the Balrog’s unexpected wake-up call. (We’ll never will know how tight Durin’s Bane and Sauron were in the break room back at Angband in the First Age.) But the point is, the return of the Shadow can’t have helped. Especially with Orcs already milling about in greater numbers within the mountains. In any case, the calamity of the Nameless Terror leads to the flight of the Dwarves from their favorite kingdom. And this, in turn, gives the Orcs of the Misty Mountains some serious elbow room. Perfect for all that follows.

Even so, except for that one-time stirring of Orcs in the mountains at one point, Middle-earth gets about two thousand four hundred years of Orc-free highs and lows. Even trolls are not seen much; I imagine they become the stuff of legend (except to Elves, who would remember firsthand encounters quite well).

We learn from Appendix B and the Tale of Years that the Istari come onto the scene around the year 1000—approximately fifty years before that darkness started creeping over Mirkwood. (Well played, Valar! It’s almost like you knew what the “reincarnation” period, so to speak, was for an evil Maia whose physical form was “slain” by an Elf-king and a Númenórean king.) We’re also told that the Istari had come “to contest the power of Sauron, and to unite all those who had the will to resist him.” We know that not all the wizards do their job properly, but we do know that at least Mithrandir, P.I., is on the case!

Thus we come to Gandalf the Grey and the Case of the Growing Shadow. In the year 2063 he starts to nose around the fortress of Dol Guldur in Mirkwood and, because Sauron isn’t ready to be revealed—much less confronted by messengers from the Far West—he makes like an Entwife and leaves. He lies low somewhere far away in the East. This is the period of time Appendix B calls the Watchful Peace, and it spans nearly four hundred years. We’re not told as much, but I bet that the Orc population plateaus during this time.

But then, the Watchful Peace ends and, with Gandalf no longer sniffing around his digs, Sauron “returns with increased strength” to squat once more in Dol Guldur. Twenty years after that, his “evil things” initiatives bear more fruit:

c. 2480 Orcs begin to make secret strongholds in the Misty Mountains so as to bar all the passes into Eriador. Sauron begins to people Moria with his creatures.

Catch that? He peoples Moria. Don’t ask me how, exactly. Sauron is a great spirit of malice, and he was once Morgoth’s greatest servant, so we’re talking ancient power and influence. Orcs may be able to procreate, but left to their own devices as they were for more than a millennium, their mojo doesn’t seem so strong. (A fact somewhat contradicted in later writings; but that’s for another day!) It takes the Shadow of the Dark Lord, which “holds them all in sway,” to surge Orc numbers this late into the Third Age. And it’ll be the same Shadow that will one day leave them scattered and “witless” when it’s been thrown down for good.

But this! The year 2480, this is when orcs make a big comeback, and start showing up in all the stories we’re more familiar with:

- The capture and torment of Celebrían in the Redhorn Pass.

- Orcs invading Eriador (i.e. going down into the lands under the open sky), a few times.

- Orcs invading the Shire (wherein Bandobras Took invents the game of golf with a goblin king’s head).

- The death of Thrór at the hands of Azog the Orc-chieftain and the official War of the Dwarves and Orcs.

- Orcs harrassing Rohan.

- Arador (Aragorn’s grandfather) is killed by trolls, and Arathorn II is killed by Orcs. Baby Aragorn is sent to Rivendell.

- Orcs surge from the Misty Mountains, led by Bolg of the North, and get involved in the Battle of the Five Armies.

And so on. Orcs are all over the place now! Recall Frodo’s vision at Amon Hen:

But everywhere he looked he saw the signs of war. The Misty Mountains were crawling like anthills: orcs were issuing out of a thousand holes.

Okay, all this talk of Orcs and war and the return of the Shadow means it’s time for a graphic to hang some of these dates on.

This all confirms the rumors Frodo heard back in the Shire. Sauron is not only back but has upped his game, settled into Mordor with his newly renovated Dark Tower. Better still: He no longer faces the same level of opposition he once did at the end of the Second Age. Nothing in the last few thousand years can hold a Morgul-candle to that Last Alliance that took him down the first time (or second time, if we count the downfall of Númenor). Men are divided or under his thumb. Dwarves are isolated in their far-flung mountains (not even in Moria anymore), so no problem there. And Elves? Don’t get me started on how diminished they are!

So yeah, commanders Shagrat and Gorbag may daydream about going off on their own thing “like old times.” Orcs can be crappy servants, but are effective in war due to their large numbers. They serve out of fear, not loyalty, and are fueled by the malice Sauron inspires in them. Still, even they hate him. But if Isildur had dropped the Ring into the Garbage Disposal of Doom as Elrond had advised way back when, there might never have been a Shagrat or a Gorbag. Orcs would have remained few, maybe have died out altogether by 3019. But Isildur didn’t do the thing, the Shadow passed away and came back again, and the War of the Ring happens.

So suppose Shagrat does manage to escape Mordor, against all odds, in the end. Would he really be able muster up some trusty lads and keep doing Orc things on his own? Probably not. Because in “The Field of Cormallen,” when Sauron is defeated, Tolkien uses that insect metaphor one last time, and then some:

As when death smites the swollen brooding thing that inhabits their crawling hill and holds them all in sway, ants will wander witless and purposeless and then feebly die, so the creatures of Sauron, orc or troll or beast spell-enslaved, ran hither and thither mindless; and some slew themselves, or cast themselves in pits or fled wailing back to hide in holes and dark lightless places far from hope.

With the Dark Tower crumbled and its Lord soundly defeated, all the wind goes out of the Orc-balloon. They are donezo. Shagrat’s dreams are surely squashed now. If he is alive, he is no shape to go setting up on his own. Orcs are not of the Free Peoples, and the best the survivors can do is cower, and someday die out. Not like the Haradrim and the Easterlings who turned out for this war. Not like actual human beings.

And the King pardoned the Easterlings that had given themselves up, and sent them away free, and he made peace with the peoples of Harad; and the slaves of Mordor he released and gave to them all the lands about Lake Núrnen to be their own.

In The Lord of the Rings, we really don’t know anything about the spirits of Orcs, or if they even have souls at all (or fëar, a term used elsewhere). Not yet. Tolkien doesn’t explore Orc origins until years after the publication of LotR. But it will gnaw at him—as I’ll discuss next time—this need to make even these monstrous foes “consonant with Christian thought.” But having said that, Tolkien did clearly associate the orcish moral character with real human behavior. Even that of his own countrymen—maybe especially them. In a 1954 letter (#153 in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien), he called Orcs “fundamentally a race of ‘rational incarnate’ creatures, though horribly corrupted, if no more so than many Men to be met today.”

The ‘orc-crowd’

All right. So I guess it’s time to address the oliphaunt in the room: A lot has been written about Tolkien’s conception of good and evil (including Orcs) in terms of race, and certainly modern-day alt-right and white supremacists have tried to appropriate Tolkien for their own use. I feel secure in stating that he would not have given them the time of day. When a German firm, hoping to publish a translation of The Hobbit, inquired whether he was of Aryan descent, he wrote back to say that particular translation could “go hang” and that he rejected their country’s “wholly pernicious and unscientific race-doctrine” (letter #29 from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien). And while I’d agree that this Oxford professor of philology and Medieval literature (born in 1892) wasn’t as sensitive to the concept of race in the way that we at least try to be today, I also believe he was decades ahead of his peers and would measure up better than most of us in present times. Again, if he’d been around to experience our generation.

My opinion is that many fans, critics, and even scholars miss the point Tolkien was making. He saw Orcs not in terms of race or ethnicity but in the loathsome moral behavior of anyone, be they human or mythical monster-men. For example, we knew he had a low opinion of technological progress—for progress’ sake—and particularly of the cutting down of trees. In a correspondence with his son (letter #66), he wished the “‘infernal combustion’ had never been invented” or at least “put to rational uses,” for it fouled the air and spoiled the quiet of his garden. In the chapter “Treebeard,” the old Ent himself says this of Saruman and the Orcs who’ve come into his woods:

‘He and his foul folk are making havoc now. Down on the borders they are felling trees – good trees. Some of the trees they just cut down and leave to rot – orc-mischief that’

Wanton destruction and especially waste go hand-in-hand with “orc-work” in Tolkien’s book. In “The Black Gate Opens,” as Aragorn’s army advances on Sauron’s land, they see the first signs of the occupancy of Orcs, who in daylight have made themselves scarce.

North amid their noisome pits lay the first of the great heaps and hills of slag and broken rock and blasted earth, the vomit of the maggot-folk of Mordor;

But the greatest atrocities of Orcs—the thirst for violence, the cruelty of war—is what Tolkien saw most clearly in his fellow humans. He wrote many letters to his son Christopher during the Second World War, having himself been a veteran of the First and knowing firsthand its horrors. He hated the whole business of the war—not as a pacifist, for he understood why the war existed, but at how it brought out the worst in everyone, leading to so much misery and death. His own side was not excluded from this contempt.

In one letter (#66, in May of 1944)—mind you, this is ten years before the publication of Fellowship—he drew comparisons from his own work, with which Christopher was already familiar. And he didn’t hesitate to use the O-word. Speaking of the manner in which “we,” the English and their allies, were going about the war, he wrote:

For we are attempting to conquer Sauron with the Ring. And we shall (it seems) succeed. But the penalty is, as you will know, to breed new Saurons, and slowly turn Men and Elves into Orcs. Not that in real life things are as clear cut as in a story, and we started out with a great many Orcs on our side . . .

On our side. Here he is not associating orcs with the Axis Powers, but the Allied powers, which would include Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, the United States, and so on.

Today, when we witness the abhorrent words and actions of people, we like to use pop culture analogies. We’re quick to (rightfully) equate white supremacists with the space Nazis of the Galactic Empire. How easy it is to invoke Palpatine when we see powerful people self-aggrandizing, shunning responsibility, or dodging accountability. It comes naturally to us, with so much media to draw from, to harness the stories we love, stories filled with human truths. I think it’s why so many of us love fiction so much.

My point is, Tolkien did this, too, and well before we did. Considering the historic oral traditions of storytelling, I would argue humans have always done this. Except Tolkien used his own stories. It was very personal, for his own son was enmeshed in the war (specifically, Christopher Tolkien joined Great Britain’s Royal Air Force in 1943). In another letter to Christopher less than a year later (#96 from Letters), when the conflict was nearing its end, he yet mourns for the inhumanity of his own Englishmen—the lack of compassion, of mercy:

The appalling destruction and misery of this war mount hourly: destruction of what should be (indeed is) the common wealth of Europe, and the world, if mankind were not so besotted, wealth the loss of which will affect us all, victors or not. Yet people gloat to hear of the endless lines, 40 miles long, of miserable refugees, women and children pouring West, dying on the way. There seem no bowels of mercy or compassion, no imagination, left in this dark diabolic hour. By which I do not mean that it may not all, in the present situation, mainly (not solely) created by Germany, be necessary and inevitable. But why gloat! We were supposed to have reached a stage of civilization in which it might still be necessary to execute a criminal, but not to gloat, or to hang his wife and child by him while the orc-crowd hooted.

The Orcs in this instance are not the defeated. Not the Nazis, the Fascists, the Empire of Japan; not the collateral refugees. Rather, they are the victors who cried for blood and for sadistic revenge, on any side. It is the moral decay of Men that concerned Tolkien, and we see it embodied in his secondary world in the Orcs, “the maggot-folk of Mordor.”

In May of 1945, Tolkien’s contempt for the Second World War really peaked. In yet another letter to his son (#100), he wrote:

Though in this case, as I know nothing about British or American imperialism in the Far East that does not fill me with regret and disgust, I am afraid I am not even supported by a glimmer of patriotism in this remaining war. I would not subscribe a penny to it, let alone a son, were I a free man.

Is it any wonder that Tolkien’s most famous story sets his “good” people (who are not without evils of their own) against an unequivocal Dark Lord who not only yokes other people with his power and lies (people who might otherwise have been good), but also commands a demonic army that represents the worst in all of us? And yet consider the words of Gandalf at the Council of Elrond:

‘For nothing is evil in the beginning. Even Sauron was not so.’

Of course, there is such a thing as point of no return. Sauron himself had a chance to repent, and nearly did, at the start of the Second Age. He passed it by. What of his creatures, though? Some of which he corrupted and bred—but the first Orcs were not his, whatever they were. More on that next time.

Jeff LaSala highly recommends two particular episodes of The Prancing Pony Podcast: #114 (Race, Tolkien, and Middle-earth) and #192 (Race, Tolkien, and Middle-earth, Revisited) for more discussion and perspectives on the subject. It’s a continuing conversation.