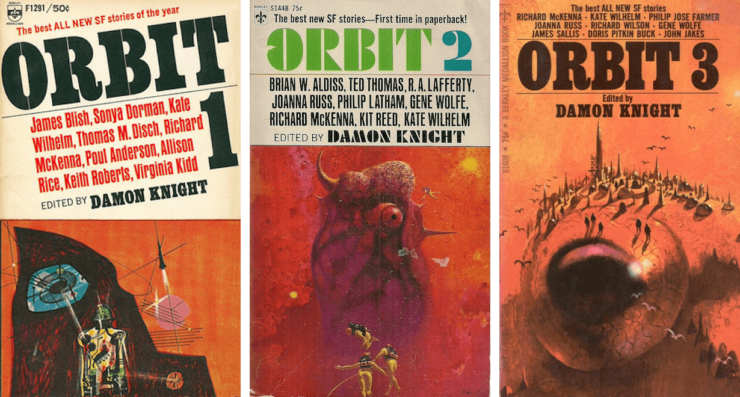

There are editors who have assembled impressive numbers of anthologies. There are editors who have given the world anthologies of remarkable quality. The two sets overlap, but perhaps not as much as one would like. Damon Knight’s Orbit series is an example of an oeuvre that sits in the overlap between quantity and quality.

Some basic facts: The first Orbit anthology was sent to bookstores in 1966. The final volume of Orbit was published in 1980. Between 1966 and 1980, no less than twenty-one volumes appeared. While individual volumes might seem slim by the standards of, oh, any given Ceres-sized Dozois Best SF annual, all twenty-one add up to a magisterial 5008 pages (5381 if I include 1975’s The Best From Orbit, which reprinted material from Orbits 1 through 10). Early volumes were surprisingly open to women authors, although the series trended heavily male in the later issues. Authors were almost all (but not entirely) White.

If one wants to helm a long-running series, it helps to have a guiding ethos.1 To quote Knight himself, Knight believed that

…science fiction is a field of literature worth taking seriously, and that ordinary critical standards can be meaningfully applied to it: e.g., originality, sincerity, style, construction, logic, coherence, sanity, garden-variety grammar.

This belief fueled Knight’s notoriously caustic reviews, in which he chastised otherwise beloved SF works for egregious flaws in prose, plotting, characterization, and basic plausibility. Orbit was a more positive expression of his standards. Rather than complain about what was missing, Knight assembled examples of the sort of work he wanted to see.

Given Knight’s critical proclivities, it’s not surprising that much of the material that appeared in Orbit was if not fully New Wave SF, then definitely New Wave-adjacent. The contributors’ prose tends towards ambitious; characters have interior lives; plot is sometimes a distant second to style. That said, Knight’s tastes could be wide-ranging: in amongst the Laffertys, the Wolfes, and the Wilhelms, there are stories by Laumer and by Vinge, both Vernor and Joan D.

Another useful metric: awards. A quick skim through all 5008 pages reveals at least twenty-one works considered for the Nebula (four wins, if I recall correctly), and at least ten considered for the Hugo. Nebulas being an awards granted by writers and the Hugo by fans, one gets the sense that Orbit was populated by writer’s writers, rather than popular authors, which may be true to a degree…but consider: the series survived, by means of sales, for twenty-one volumes. Knight had won over some devoted readers.

An overall summary of awards provides a misleading average: yes, the series averaged a Nebula nod (sometimes a win!) almost every volume and a spot on Hugo ballots every other volume. However, a closer look reveals that the nominations2 were very unevenly distributed: of the twenty-one Nebula candidates, six appeared in Orbit 6, and four in Orbit 7, while of the ten Hugo nods, two were in Orbit 7.

(This egregious display of quality in Orbit 6 and Orbit 7 sparked a backlash: old guard SFWA members deliberately coordinated their votes to ensure that the Nebula went, not to one of Knight’s New Wave offerings, but rather to No Award. More details here.)

The uneven reward and nomination distribution hints at the reason the series ended. If Knight had been able to keep up the pace, we would be reviewing Orbit 84 today. Knight’s effort was impressive, but not sustainable. Orbits 6 and 7 were the high note; after those volumes, there were fewer nominations. As well, while noteworthy works appeared in volumes right up until the series ended, individual Orbits became rather hit-or-miss, as detailed here.

Orbit’s original publisher Berkley/Putnam belatedly discovered that sales had begun to slip after Orbit 6; a discussion of whether the issue was content or packaging ended the relationship with Berkley/Putnam after Orbit 13. New publisher Harper eschewed paperback editions of subsequent Orbits. Sales of the hardcovers were disappointing and the series ended with Orbit 21.

Still, twenty-one Nebula nominations, at least four wins, and a sack of Hugo pins is nothing to sniff at. Knight could justly take pride in publishing debut or early-career stories by Carol Carr, Steve Chapman, Gardner Dozois, George Alec Effinger, Vonda N. McIntyre, Doris Piserchia, Kim Stanley Robinson, James Sallis, Kathleen M. Sidney, Dave Skal, Joan D. Vinge, Gary K. Wolf, and Gene Wolfe.

Where should the Orbit-curious start? On the minus side, the books are all out of print. On the plus side, used copies are easy to find. One could just hunt down all twenty-one volumes (twenty-two with the Best From!). A more affordable option would be to focus on Orbit 6 and Orbit 7. An even more affordable option would be to order a copy of The Best From Orbit (with the caveat that it draws exclusively from Orbits 1 through 10 and you will miss interesting works from later volumes).

Some readers may prefer other strategies to tackle the Orbit series. Comments are below!

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and the Aurora finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, is eligible to be nominated again this year, and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]“I would like to be paid to edit anthologies” does technically count but isn’t a strong recommendation.

[2]Here I would make a mystic hand gesture to ward off WSFS pundits eager to discuss the very important difference between “nominee” vs “finalist” but as I recall, the nomenclature changed long after Orbit 21 was published.

I grew into science fiction with the holy “trinity” of anthologies: Orbit, Universe, New Dimensions. Took me years to realize that I was being indoctrinated in New Wave sf. I just thought it was good writing, creative and exciting.

I find myself wondering how Knight went about acquiring stories for these, especially with the nearly or completely unknown authors. Gardner Dozois had one story in IF before finding himself in the army and then wound up in Orbit almost as soon as he got out. Wolfe also had one SF publication and a couple of stories in college magazines and/or less reputable men’s magazines before Orbit. KSR’s very first publication was in Orbit. I suppose it’s possible he was snapping these newcomers up from Clarion, since a couple of them also appeared in a Clarion anthology, but I wonder if they were all Clarion alumni.

2: Knight talks about issues like that in Orbit 21.

The later Orbits definitely had some Clarionites published in Orbit, but not that many for each book. I had a story in Orbit 17 that was first workshopped at Clarion, but most of the other writers were not recent Clarion attendees. On the other hand, Damon was one of founders of Clarion and most active young writers went to Clarion, so I can’t imagine an Orbit without a Clarion writer or two.

Can Lafferty fans explain to me the virtues that I am overlooking?

Lafferty’s fans appreciate his humor, a rare science fiction commodity.

I’m a Lafferty fan– in fact, I reached a point where it seemed like the only story I’d like in an Orbit anthology would be the one by Lafferty.

I’m not sure Lafferty would win on all of ” originality, sincerity, style, construction, logic, coherence, sanity, garden-variety grammar.”.

Originality, certainly.

As for what’s to like, it’s not just the humor, though there’s quite a bit of humor, it’s the weirdness. For me, there’s a sense of something almost but not quite seen.

Something I’ve noticed about Heinlein and which I think also applies to Lafferty is a feeling that the world is interesting. It’s full of cool details. They aren’t otherwise especially similar.

For the Lafferty-obsessed, there’s also _Lafferty in Orbit_, a collection of his stories from Orbit, but it isn’t cheap.

Did any other writers get collections of their work from Orbit?

I wonder why the publisher went with expensive hardcovers for the last books, instead of more affordable paperbacks?

There is a Kindle edition of these anthologies.

8 MMPB get much larger print runs. Perhaps the publisher did not think they could sell that many?

@8/@10: hardcover also gets library sales; half a century ago, libraries (at least in the US) were very unlikely to buy paperbacks due to durability and (maybe) reputation issues. These days durability at least is less of a factor; there are so many books that libraries seem to assume that most will be moved offsite if not disposed of after some time. OTOH, I’ve seen figures that present-day publishers will often do a hardcover and not proceed to MMPB; it’s possible the margins have gotten so small (given return policies, HSAR.com, etc.) compared to HC that MMPB publication is risky given some fixed expenses.

@5: I guess it’s a matter of taste. There are some Lafferty stories in which his reactionary social views are foregrounded; I’ve never thought much of “Primary Education of the Camiroi”. However, many of them have a unique and wonderful strangeness; how a reader reacts to that strangeness is probably very individual. (The fact that I was started on GIlbert and Sullivan very early may contribute to my appreciation for paradox and absurdity, even if the operettas now seem significantly conventional.) I think my first Lafferty story was “Narrow Valley” (1966), which I read when it was fairly new and am still fond of; it has some social flaws by today’s standards but it also has virtues, one of which is snickering at the social models of its time.

There is a 2 volume collection of Kate Wilhelm’s Orbit stories.