The now-famous story goes that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg were on vacation in 1977: Spielberg had come off the recent success of Close Encounters and Lucas was running from Star Wars, which he presumed was going to flop. Spielberg told his buddy George that he wanted to direct a James Bond film and Lucas said (something to the effect of), “Pfft. I’ve got something way better than that.”

And then they made Raiders of the Lost Ark.

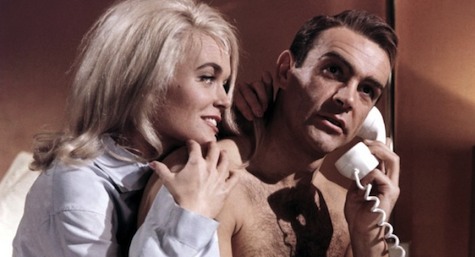

As a result, Indiana Jones is often thought of as some kind of inheritor to the James Bond mantle. In a way that seems a logical choice; they are adventurers who deal with high-octane thrills, lovers of women, and have a similarly wry sense of humor. They have jobs that require a fair share of globe-trotting and an ability to improvise that is unmatchable. They both were in play during the Cold War—that is, if you count Crystal Skull in you personal continuity, which I know many fans are against. Sean Connery was deliberately cast as Henry Jones Sr. in The Last Crusade because, according to Spielberg, only James Bond could be the father of Indiana Jones. And it’s fair to say that Indy was filling a gap left by the 80s Bond era—regardless of your feelings on later-Moore and early-Dalton, their films get a lot of flak. Indy was the sensible alternative while fans waited for new Bond films that were more to their taste.

But despite all this, Bond and Indy really couldn’t be more different. And I’m not just talking about their jobs or their attire; their choices, as two separate men, do not make them the same kind of hero at all. Continually comparing them is a blunt exercise at this point. They just don’t match up.

Start with Point of Divergence Number One: Professor Bond is a patently awful idea.

We know that Indy ignores his job when he’s got ancient talismans to locate, but when we see him in class, he’s actually good at the gig. He knows how to lecture, what books to assign for course reading, and treats his students in a professional (if confused) manner no matter how hard they flirt with him. We can infer that Indy’s teaching job is the way he pays bills rather than his passion, but that’s also a pointed difference; at the end of the day, Indiana Jones is just another working stiff. He operates as an archaeologist for his own personal satisfaction and out of a duty to history—because that belongs in a museum, not in his basement—and not because he gets cut a big check at the end of the day. Sometimes people pay him well for his services, but you have to figure that a large portion of his income is going toward more trips into the jungle/desert/mountains. And when he gets there, he sleeps in tents or on the ground.

Bond works for the government to do what the government deems necessary. He has all the money he needs in order to do that job, and is rarely sleeping in the dirt. He is someone else’s tool—despite rampant self-centeredness in most incarnations, his missions are for a larger good and have very little to do with his personal desires. He doesn’t need another job. He doesn’t have to keep watch on his pension. He doesn’t have to foster the next generation.

Much is made of Indy’s woman-a-movie tally, but his relationships couldn’t be more different from Bond’s habitual non-relationships. 007 often sleeps with more than one woman a film, and respects practically none of them. There’s his eventual wife, sure, and an argument can be made that Daniel Craig’s version has a very different tack and rapport with women, but for Bond when Indiana Jones was conceived… the spy-who-loved-’em-all had some appalling tendencies where sex and consent were concerned. Calling him a rapist outright is basically fair game. Saying that he uses women is an understatement. That he considers them a means to an end is equally obvious, even when he’s protecting them.

We see Indiana Jones with three different women over the course of the initial trilogy. There’s Willie, who is the least suited to his adventures, who he teases and cajoles. But there’s never a question as to whether or not she’s open to his advances, and it’s fair to say that they both know their fling is going nowhere serious—it’s just convenient in the here and now. There’s Elsa who turns out to be a Nazi spy, which at first glance looks like it comes right out of the Bond playbook. Yet in a very un-Bond twist, we find that Indy is genuinely hurt over her betrayal. He cares for Elsa even after the revelation of her allegiances, so much so that after she has sold him out, he still attempts to save her life. The audience is signaled to write her off—Henry Jones Sr. has no problem distancing himself on their affair—but Indy refuses to. It adds an odd touch of sadness that one might not have expected from the end of Last Crusade; it would have been much simpler for Indiana to shout “You deserved it!” as Elsa falls into the abyss, but he’s just not that kind of man.

And then there’s Marion Ravenwood. Indy was no prince to her—in fact, we know that she fell in love with him at a very young age and that he did not break up with her in a suitably mature fashion. But due to his involvement with Marion’s father and his work, we can deduce that this was no simple affair; he was also likely quite young (though older than her), panicked over how serious the relationship was getting, and bolted. Which is what a lot of people do when they overthink their first major relationships.

His loss, because Marion is easily the best suited to him, to his life and temperament and flaws. He clearly knows it, he’s just incredibly difficult on the point. There are many fans who showed irritation over Indy’s marriage Marion at the end of Crystal Skull, but I’d cite that as one of the few things that movie got right. Because he’s not a callous spy whose double life makes certain that he can never, ever have attachments. In fact, Indy’s life calls for the presence of friends, allies, lovers. Family is how Indy operates. It’s how he’s managed to stay alive as long as he has—people love him and want to help him.

Has Bond ever had a kid sidekick who pierced through one disturbing veil of mind control with the words “I love you” and a quick second degree burn to his chest? I rest my case. Just the thought of Bond getting close to an impressionable child makes you twitch. But Indy is good with kids, half-adopts Short Round for a time and presumably finds him a good home once their adventures are done. He’s not the most moral person you’ll ever meet, but he’s basically a nice guy.

And here’s another thing: Indiana Jones is a damned klutz.

There, I said it. Sure, Bond is funny in places, mostly if you’re a fan of puns. But Indy has always been funnier than the super spy, and that’s because he constantly screws up. He comes off suave when he’s dragging from a rope behind a giant truck, but let’s not forget—this is a guy who shot a master swordsman in the streets of Cairo because he forgot where his own sword wandered off to. A guy who set off a series of booby traps because he misjudged how much of a weight difference there was between sand and gold. (How do you let sand out of that bag—do you have any idea how flipping heavy gold is, Indy? Do you?) A guy who didn’t bother to check who he was renting his getaway plane from in Shanghai, who never noticed that Elsa talked of Nazis in her sleep, who knocks out uniformed men to take their clothes only to find out that they’re several sizes too small. (This happens more than once.)

His motto is, handily, “I don’t know, I’m making this up as I go.”

You know who isn’t making those mistakes on a regular basis? Yeah, you do know who. Because Bond is about wish fulfillment. He’s the best because we want a glimpse of what it feels like to be the best. So he knows how many bullets you’ve fired, and he can tell that you’re working for the bad guy, and he’s not going to crack no matter how well you’ve devised those nasty tortures. And on the rare times he doesn’t know, that he can’t handle the pain, it’s decidedly not funny at all. It’s tragic. Unless you’re Roger Moore, because you’re already wearing bellbottoms and we stopped taking you seriously a long time ago.

It’s entirely possible that a lot of this has to do with who is portraying him; Indy would have been a much different guy if, say, Tom Selleck had really sold his screen-test and nabbed the part. There are glimmers of darkness running through the Raiders script that aren’t really built up to their full potential, and that’s likely because Harrison Ford wasn’t into playing mean at that point in his career. He built his legendary status on being charming, glib, and knowing when to pout boyishly through his stubble. When he arrives at Marion’s bar and tells her he never meant to hurt her, you can see he means it, but in another actor’s hands he could have come across much more sinister. Moreover, the Indiana Jones figure is inherently American—which naturally gives him more of a cowboy bent than a cold British gentleman one. That’s a huge divergence, one that I’m not sure any comparison could come back from, unless we want to align Imperialism and frontiersman and start getting really heavy with the note-taking.

Indiana Jones has a mythic quality to him, certain ’superpowers’ if you like, but he is not the same kind of hero as the essential MI-6 agent. If he were, that silent man with his back turned on the camera during the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark would have been all we ever knew of him. So while it’s fun to ruminate on Bond being the only dad for him, you’ll need a lot more to convince me that they should be counted in the same canon of heroes.

Emmet Asher-Perrin went through a period in her childhood where she tried to become Short Round because she really wanted to be Indy’s best friend. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.