We may not know why, or when, or for what, but we will all, in our lives, lose someone we love.

Loss is not the whole of the story, of course. All too often, death itself is shocking, awful, to say nothing of the terrible tales that culminate there, but it’s only when we let go—of the memory, the expectation, the guilt or need or even relief—it’s only then than we begin to come to terms with the end.

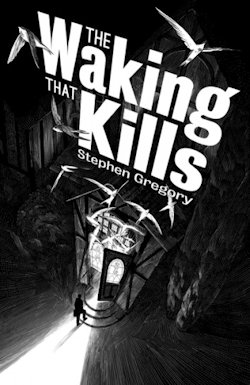

Before The Waking That Kills is over, teacher Christopher Beale will have learned to let go of his father. Though his father is still alive at the start of this short novel—Stephen Gregory’s first for five years—he is a sad shadow of the man he once was. A monumental mason by trade, which is to say someone who carves names and dates on graves, Christopher’s father has had a stroke, and lives now in a nursing home in Grimsby, England; bewildered, bitter and impotent.

Christopher himself has been working in Borneo for seven years or so. It’s a credit to his character that he hightails it home when he hears of his father’s condition, ostensibly to be there for the man that made him, but he is, alas, distracted; trapped, perhaps, in an increasingly sinister scenario. “From the sweet, seductive, pitcher-plant entrapment of Borneo, to the Lincolnshire wolds” he goes, to take a job tutoring a troubled teenager.

When he drives his father’s hearse to Chalke House, however, where he will live for the length of the sweltering summer that’s just begun, Christopher finds that his status as a teacher is in truth a token. Instead, he is to be a friend to Lawrence Lundy first, and a father-figure afterwards, given the accidental death of his dad, whose memory Lawrence refuses to let lie.

He is a hard boy just to befriend, however. And it’s clear from the first that he and his mother are keeping secrets from Christopher, though the truth will only out when he grows closer to both…

Like the Lundys, who welcome Christopher with warmth and wine, respect and inevitably, yes, sex, The Waking That Kills is a book that lulls us into a false sense of security:

It was May. The woodland was busy with birdsong, and everywhere was bursting with the fresh greenery of brambles and nettles and sweet new grasses. And yet, somehow, a whispering uneasiness seemed to lie among the rambling acres of Chalke House. Despite the fanfare of the wren, despite the watery song of the robin and the fluting of the blackbird, the morning threw a smothering gauziness among the trees and across the overgrown lawns. The songs of the birds were oddly muted by something in the air… and as the boy and I strolled further from the house where the cover of the trees grew denser still, I began to feel it was he, the boy, who wore a cloak of stillness, his own space, his own quietness, which damped all the sounds around him.

Our protagonist dismisses this impression initially, reasoning that Lawrence just needs someone to treat him decently, but the dreamlike quality of Christopher’s time in Chalke House and the pretty wilderness persists, becoming darker and more disturbing as the strange summer stretches:

When does a dream become a nightmare? What is the transitional moment, when the pleasant, random ridiculousness of a dream alters and shifts and it tinged with fear?

I could feel it happening at Chalke House. The woman—her laughter, which had seemed so blithe and few, was jarring into the cackle of a woodpecker; her silvery body, which had come to me as a miraculous sprite, was pinning me down. The boy—his teenage gawkiness, as daft and clumsy as my boys in Borneo, was now imbued with a strange, nude, muscular strength.

And their collusion. The two of them. I’d had an inkling when I’d arrived that they were riven somehow, there was a rift I was required to heal. [But] not now.

The Waking That Kills, which takes its enticing title from one of Virginia Woolf’s celebrated letters, is the fifth novel by one of the horror genre’s most underrated authors. Granted, Gregory hasn’t ever been particularly prolific: though his 1986 debut, The Cormorant, was named the winner of the Somerset Maugham Award and subsequently made into a feature film starring Ralph Fiennes (He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named to you and me) by the BBC, his other efforts have attracted little to no notice, and fallen out of print in the years since.

A regrettable state of affairs, not least because The Waking That Kills would otherwise serve as an wonderful introduction to his work, which Publishers Weekly teaches us has “the hypnotic power of Poe.” An appropriate point of reference, certainly, however Gregory’s new novel has much more in common with The Cormorant, which also revolves around the legacy of those we have loved and lost. To boot, The Waking That Kills is in part about a bird: the swift, in this instance, which Lawrence takes an unhealthy interest in, resulting, ultimately, in “such a blurring of nightmare and reality that it was impossible to tell which was which.”

At barely 200 pages The Waking That Kills doesn’t last as long as I wish it did, and it has its miscellaneous hiccups, most notably some overbearing characterisation. On the other hand, its setting and atmosphere are so darkly fantastic that the entire is likely to leave a disproportionately distinct impression on its readers, may we be legion. As an insidious novel that gets under your skin and itches insatiably from within, The Waking That Kills does the business brilliantly—and beautifully, too.

The Waking That Kills is available November 12th from Solaris.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.