Tor.com is pleased to offer the following excerpt from Brandon Sanderson’s Words of Radiance, book two of The Stormlight Archive. Be sure to check back for further excerpts and sneak peeks in the weeks to come, leading up to the book’s release on March 4th!

Following the events of The Way of Kings, Sanderson returns us to the remarkable world of Roshar, where the war between humans and the enigmatic Parshendi will move into a new, dangerous phase.

Dalinar leads the human armies deep into the heart of the Shattered Plains in a bold attempt to finally end the war. Shallan is set on finding the legendary and perhaps mythical city of Urithiru, which Jasnah believes holds a secret vital to mankind’s survival on Roshar. Kaladin struggles to wear the mantle of the Windrunners as his old demons resurface. And the threat of the Voidbringers’ return hangs over them all…

Also, we’ve opened up a spoiler thread here for discussion of the new chapters.

We had never considered that there might be Parshendi spies hiding among our slaves. This is something else I should have seen.

—From the journal of Navani Kholin, Jesesan 1174

Shallan sat again on her box on the ship’s deck, though she now wore a hat on her head, a coat over her dress, and a glove on her freehand—her safehand was, of course, pinned inside its sleeve.

The chill out here on the open ocean was something unreal. The captain said that far to the south, the ocean itself actually froze. That sounded incredible; she’d like to see it. She’d occasionally seen snow and ice in Jah Keved, during the odd winter. But an entire ocean of it? Amazing.

She wrote with gloved fingers as she observed the spren she’d named Pattern. At the moment, he had lifted himself up off the surface of the deck, forming a ball of swirling blackness—infinite lines that twisted in ways she could never have captured on the flat page. Instead, she wrote descriptions supplemented with sketches.

“Food…” Pattern said. The sound had a buzzing quality and he vibrated when he spoke.

“Yes,” Shallan said. “We eat it.” She selected a small limafruit from the bowl beside her and placed it in her mouth, then chewed and swallowed.

“Eat,” Pattern said. “You… make it… into you.”

“Yes! Exactly.”

He dropped down, the darkness vanishing as he entered the wooden deck of the ship. Once again, he became part of the material—making the wood ripple as if it were water. He slid across the floor, then moved up the box beside her to the bowl of small green fruits. Here, he moved across them, each fruit’s rind puckering and rising with the shape of his pattern.

“Terrible!” he said, the sound vibrating up from the bowl.

“Terrible?”

“Destruction!”

“What? No, it’s how we survive. Everything needs to eat.”

“Terrible destruction to eat!” He sounded aghast. He retreated from the bowl to the deck.

Pattern connects increasingly complex thoughts, Shallan wrote. Abstractions come easily to him. Early, he asked me the questions “Why? Why you? Why be?” I interpreted this as asking me my purpose. When I replied, “To find truth,” he easily seemed to grasp my meaning. And yet, some simple realities—such as why people would need to eat—completely escape him. It—

She stopped writing as the paper puckered and rose, Pattern appearing on the sheet itself, his tiny ridges lifting the letters she had just penned.

“Why this?” he asked.

“To remember.”

“Remember,” he said, trying the word.

“It means…” Stormfather. How did she explain memory? “It means to be able to know what you did in the past. In other moments, ones that happened days ago.”

“Remember,” he said. “I… cannot… remember…”

“What is the first thing you do remember?” Shallan asked. “Where were you first?”

“First,” Pattern said. “With you.”

“On the ship?” Shallan said, writing.

“No. Green. Food. Food not eaten.”

“Plants?” Shallan asked.

“Yes. Many plants.” He vibrated, and she thought she could hear in that vibration the blowing of wind through branches. Shallan breathed in. She could almost see it. The deck in front of her changing to a dirt path, her box becoming a stone bench. Faintly. Not really there, but almost. Her father’s gardens. Pattern on the ground, drawn in the dust…

“Remember,” Pattern said, voice like a whisper.

No, Shallan thought, horrified. NO!

The image vanished. It hadn’t really been there in the first place, had it? She raised her safehand to her breast, breathing in and out in sharp gasps. No.

“Hey, young miss!” Yalb said from behind. “Tell the new kid here what happened in Kharbranth!”

Shallan turned, heart still racing, to see Yalb walking over with the “new kid,” a six-foot-tall hulk of a man who was at least five years Yalb’s senior. They’d picked him up at Amydlatn, the last port. Tozbek wanted to be sure they wouldn’t be undermanned during the last leg to New Natanan.

Yalb squatted down beside her stool. In the face of the chill, he’d acquiesced to wearing a shirt with ragged sleeves and a kind of headband that wrapped over his ears.

“Brightness?” Yalb asked. “You all right? You look like you swallowed a turtle. And not just the head, neither.”

“I’m well,” Shallan said. “What… what was it you wanted of me, again?”

“In Kharbranth,” Yalb said, thumbing over his shoulder. “Did we or did we not meet the king?”

“We?” Shallan asked. “I met him.”

“And I was your retinue.”

“You were waiting outside.”

“Doesn’t matter none,” Yalb said. “I was your footman for that meeting, eh?”

Footman? He’d led her up to the palace as a favor. “I… guess,” she said. “You did have a nice bow, as I recall.”

“See,” Yalb said, standing and confronting the much larger man. “I mentioned the bow, didn’t I?”

The “new kid” rumbled his agreement.

“So get to washing those dishes,” Yalb said. He got a scowl in response. “Now, don’t give me that,” Yalb said. “I told you, galley duty is something the captain watches closely. If you want to fit in around here, you do it well, and do some extra. It will put you ahead with the captain and the rest of the men. I’m giving you quite the opportunity here, and I’ll have you appreciate it.”

That seemed to placate the larger man, who turned around and went tromping toward the lower decks.

“Passions!” Yalb said. “That fellow is as dun as two spheres made of mud. I worry about him. Somebody’s going to take advantage of him, Brightness.”

“Yalb, have you been boasting again?” Shallan said.

“ ’Tain’t boasting if some of it’s true.”

“Actually, that’s exactly what boasting entails.”

“Hey,” Yalb said, turning toward her. “What were you doing before? You know, with the colors?”

“Colors?” Shallan said, suddenly cold.

“Yeah, the deck turned green, eh?” Yalb said. “I swear I saw it. Has to do with that strange spren, does it?”

“I… I’m trying to determine exactly what kind of spren it is,” Shallan said, keeping her voice even. “It’s a scholarly matter.”

“I thought so,” Yalb said, though she’d given him nothing in the way of an answer. He raised an affable hand to her, then jogged off.

She worried about letting them see Pattern. She’d tried staying in her cabin to keep him a secret from the men, but being cooped up had been too difficult for her, and he didn’t respond to her suggestions that he stay out of their sight. So, during the last four days, she’d been forced to let them see what she was doing as she studied him.

They were understandably discomforted by him, but didn’t say much. Today, they were getting the ship ready to sail all night. Thoughts of the open sea at night unsettled her, but that was the cost of sailing this far from civilization. Two days back, they’d even been forced to weather a storm in a cove along the coast. Jasnah and Shallan had gone ashore to stay in a fortress maintained for the purpose—paying a steep cost to get in—while the sailors had stayed on board.

That cove, though not a true port, had at least had a stormwall to help shelter the ship. Next highstorm, they wouldn’t even have that. They’d find a cove and try to ride out the winds, though Tozbek said he’d send Shallan and Jasnah ashore to seek shelter in a cavern.

She turned back to Pattern, who had shifted into his hovering form. He looked something like the pattern of splintered light thrown on the wall by a crystal chandelier—except he was made of something black instead of light, and he was three-dimensional. So… Maybe not much like that at all.

“Lies,” Pattern said. “Lies from the Yalb.”

“Yes,” Shallan said with a sigh. “Yalb is far too skilled at persuasion for his own good, sometimes.”

Pattern hummed softly. He seemed pleased.

“You like lies?” Shallan asked.

“Good lies,” Pattern said. “That lie. Good lie.”

“What makes a lie good?” Shallan asked, taking careful notes, recording Pattern’s exact words.

“True lies.”

“Pattern, those two are opposites.”

“Hmmmm… Light makes shadow. Truth makes lies. Hmmmm.”

Liespren, Jasnah called them, Shallan wrote. A moniker they don’t like, apparently. When I Soulcast for the first time, a voice demanded a truth from me. I still don’t know what that means, and Jasnah has not been forthcoming. She doesn’t seem to know what to make of my experience either. I do not think that voice belonged to Pattern, but I cannot say, as he seems to have forgotten much about himself.

She turned to making a few sketches of Pattern both in his floating and flattened forms. Drawing let her mind relax. By the time she was done, there were several half-remembered passages from her research that she wanted to quote in her notes.

She made her way down the steps belowdecks, Pattern following. He drew looks from the sailors. Sailors were a superstitious lot, and some took him as a bad sign.

In her quarters, Pattern moved up the wall beside her, watching without eyes as she searched for a passage she remembered, which mentioned spren that spoke. Not just windspren and riverspren, which would mimic people and make playful comments. Those were a step up from ordinary spren, but there was yet another level of spren, one rarely seen. Spren like Pattern, who had real conversations with people.

The Nightwatcher is obviously one of these, Alai wrote, Shallan copying the passage. The records of conversations with her—and she is definitely female, despite what rural Alethi folktales would have one believe—are numerous and credible. Shubalai herself, intent on providing a firsthand scholarly report, visited the Nightwatcher and recorded her story word for word.…

Shallan went to another reference, and before long got completely lost in her studies. A few hours later, she closed a book and set it on the table beside her bed. Her spheres were getting dim; they’d go out soon, and would need to be reinfused with Stormlight. Shallan released a contented sigh and leaned back against her bed, her notes from a dozen different sources laid out on the floor of her small chamber.

She felt… satisfied. Her brothers loved the plan of fixing the Soulcaster and returning it, and seemed energized by her suggestion that all was not lost. They thought they could last longer, now that a plan was in place.

Shallan’s life was coming together. How long had it been since she’d just been able to sit and read? Without worried concern for her house, without dreading the need to find a way to steal from Jasnah? Even before the terrible sequence of events that had led to her father’s death, she had always been anxious. That had been her life. She’d seen becoming a true scholar as something unreachable. Stormfather! She’d seen the next town over as being unreachable.

She stood up, gathering her sketchbook and flipping through her pictures of the santhid, including several drawn from the memory of her dip in the ocean. She smiled at that, recalling how she’d climbed back up on deck, dripping wet and grinning. The sailors had all obviously thought her mad.

Now she was sailing toward a city on the edge of the world, betrothed to a powerful Alethi prince, and was free to just learn. She was seeing incredible new sights, sketching them during the days, then reading through piles of books in the nights.

She had stumbled into the perfect life, and it was everything she’d wished for.

Shallan fished in the pocket inside her safehand sleeve, digging out some more spheres to replace those dimming in the goblet. The ones her hand emerged with, however, were completely dun. Not a glimmer of Light in them.

She frowned. These had been restored during the previous highstorm, held in a basket tied to the ship’s mast. The ones in her goblet were two storms old now, which was why they were running out. How had the ones in her pocket gone dun faster? It defied reason.

“Mmmmm…” Pattern said from the wall near her head. “Lies.”

Shallan replaced the spheres in her pocket, then opened the door into the ship’s narrow companionway and moved to Jasnah’s cabin. It was the cabin that Tozbek and his wife usually shared, but they had vacated it for the third—and smallest—of the cabins to give Jasnah the better quarters. People did things like that for her, even when she didn’t ask.

Jasnah would have some spheres for Shallan to use. Indeed, Jasnah’s door was cracked open, swaying slightly as the ship creaked and rocked along its evening path. Jasnah sat at the desk inside, and Shallan peeked in, suddenly uncertain if she wanted to bother the woman.

She could see Jasnah’s face, hand against her temple, staring at the pages spread before her. Jasnah’s eyes were haunted, her expression haggard.

This was not the Jasnah that Shallan was accustomed to seeing. The confidence had been overwhelmed by exhaustion, the poise replaced by worry. Jasnah started to write something, but stopped after just a few words. She set down the pen, closing her eyes and massaging her temples. A few dizzy-looking spren, like jets of dust rising into the air, appeared around Jasnah’s head. Exhaustionspren.

Shallan pulled back, suddenly feeling as if she’d intruded upon an intimate moment. Jasnah with her defenses down. Shallan began to creep away, but a voice from the floor suddenly said, “Truth!”

Startled, Jasnah looked up, eyes finding Shallan—who, of course, blushed furiously.

Jasnah turned her eyes down toward Pattern on the floor, then reset her mask, sitting up with proper posture. “Yes, child?”

“I… I needed spheres…” Shallan said. “Those in my pouch went dun.”

“Have you been Soulcasting?” Jasnah asked sharply.

“What? No, Brightness. I promised I would not.”

“Then it is the second ability,” Jasnah said. “Come in and close that door. I should speak to Captain Tozbek; it won’t latch properly.”

Shallan stepped in, pushing the door closed, though the latch didn’t catch. She stepped forward, hands clasped, feeling embarrassed.

“What did you do?” Jasnah asked. “It involved light, I assume?”

“I seemed to make plants appear,” Shallan said. “Well, really just the color. One of the sailors saw the deck turn green, but it vanished when I stopped thinking about the plants.”

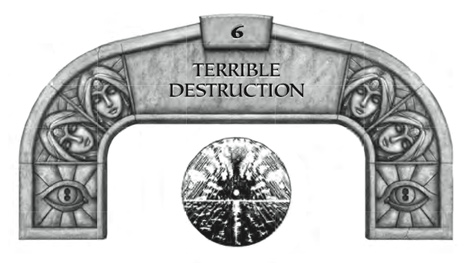

“Yes…” Jasnah said. She flipped through one of her books, stopping at an illustration. Shallan had seen it before; it was as ancient as Vorinism. Ten spheres connected by lines forming a shape like an hourglass on its side. Two of the spheres at the center looked almost like pupils. The Double Eye of the Almighty.

“Ten Essences,” Jasnah said softly. She ran her fingers along the page. “Ten Surges. Ten orders. But what does it mean that the spren have finally decided to return the oaths to us? And how much time remains to me? Not long. Not long…”

“Brightness?” Shallan asked.

“Before your arrival, I could assume I was an anomaly,” Jasnah said. “I could hope that Surgebindings were not returning in large numbers. I no longer have that hope. The Cryptics sent you to me, of that I have no doubt, because they knew you would need training. That gives me hope that I was at least one of the first.”

“I don’t understand.”

Jasnah looked up toward Shallan, meeting her eyes with an intense gaze. The woman’s eyes were reddened with fatigue. How late was she working? Every night when Shallan turned in, there was still light coming from under Jasnah’s door.

“To be honest,” Jasnah said, “I don’t understand either.”

“Are you all right?” Shallan asked. “Before I entered, you seemed… distressed.”

Jasnah hesitated just briefly. “I have merely been spending too long at my studies.” She turned to one of her trunks, digging out a dark cloth pouch filled with spheres. “Take these. I would suggest that you keep spheres with you at all times, so that your Surgebinding has the opportunity to manifest.”

“Can you teach me?” Shallan asked, taking the pouch.

“I don’t know,” Jasnah said. “I will try. On this diagram, one of the Surges is known as Illumination, the mastery of light. For now, I would prefer you expend your efforts on learning this Surge, as opposed to Soulcasting. That is a dangerous art, more so now than it once was.”

Shallan nodded, rising. She hesitated before leaving, however. “Are you sure you are well?”

“Of course.” She said it too quickly. The woman was poised, in control, but also obviously exhausted. The mask was cracked, and Shallan could see the truth.

She’s trying to placate me, Shallan realized. Pat me on the head and send me back to bed, like a child awakened by a nightmare.

“You’re worried,” Shallan said, meeting Jasnah’s eyes.

The woman turned away. She pushed a book over something wiggling on her table—a small purple spren. Fearspren. Only one, true, but still.

“No…” Shallan whispered. “You’re not worried. You’re terrified.” Stormfather!

“It is all right, Shallan,” Jasnah said. “I just need some sleep. Go back to your studies.”

Shallan sat down on the stool beside Jasnah’s desk. The older woman looked back at her, and Shallan could see the mask cracking further. Annoyance as Jasnah drew her lips to a line. Tension in the way she held her pen, in a fist.

“You told me I could be part of this,” Shallan said. “Jasnah, if you’re worried about something…”

“My worry is what it has always been,” Jasnah said, leaning back in her chair. “That I will be too late. That I’m incapable of doing anything meaningful to stop what is coming—that I’m trying to stop a highstorm by blowing against it really hard.”

“The Voidbringers,” Shallan said. “The parshmen.”

“In the past,” Jasnah said, “the Desolation—the coming of the Voidbringers—was supposedly always marked by a return of the Heralds to prepare mankind. They would train the Knights Radiant, who would experience a rush of new members.”

“But we captured the Voidbringers,” Shallan said. “And enslaved them.” That was what Jasnah postulated, and Shallan agreed, having seen the research. “So you think a kind of revolution is coming. That the parshmen will turn against us as they did in the past.”

“Yes,” Jasnah said, rifling through her notes. “And soon. Your proving to be a Surgebinder does not comfort me, as it smacks too much of what happened before. But back then, new knights had teachers to train them, generations of tradition. We have nothing.”

“The Voidbringers are captive,” Shallan said, glancing toward Pattern. He rested on the floor, almost invisible, saying nothing. “The parshmen can barely communicate. How could they possibly stage a revolution?”

Jasnah found the sheet of paper she’d been seeking and handed it to Shallan. Written in Jasnah’s own hand, it was an account by a captain’s wife of a plateau assault on the Shattered Plains.

“Parshendi,” Jasnah said, “can sing in time with one another no matter how far they are separated. They have some ability to communicate that we do not understand. I can only assume that their cousins the parshmen have the same. They may not need to hear a call to action in order to revolt.”

Shallan read the report, nodding slowly. “We need to warn others, Jasnah.”

“You don’t think I’ve tried?” Jasnah asked. “I’ve written to scholars and kings all around the world. Most dismiss me as paranoid. The evidence you readily accept, others call flimsy.

“The ardents were my best hope, but their eyes are clouded by the interference of the Hierocracy. Besides, my personal beliefs make ardents skeptical of anything I say. My mother wants to see my research, which is something. My brother and uncle might believe, and that is why we are going to them.” She hesitated. “There is another reason we seek the Shattered Plains. A way to find evidence that might convince everyone.”

“Urithiru,” Shallan said. “The city you seek?”

Jasnah gave her another curt glance. The ancient city was something Shallan had first learned about by secretly reading Jasnah’s notes.

“You still blush too easily when confronted,” Jasnah noted.

“I’m sorry.”

“And apologize too easily as well.”

“I’m… uh, indignant?”

Jasnah smiled, picking up the representation of the Double Eye. She stared at it. “There is a secret hidden somewhere on the Shattered Plains. A secret about Urithiru.”

“You told me the city wasn’t there!”

“It isn’t. But the path to it may be.” Her lips tightened. “According to legend, only a Knight Radiant could open the way.”

“Fortunately, we know two of those.”

“Again, you are not a Radiant, and neither am I. Being able to replicate some of the things they could do may not matter. We don’t have their traditions or knowledge.”

“We’re talking about the potential end of civilization itself, aren’t we?” Shallan asked softly.

Jasnah hesitated.

“The Desolations,” Shallan said. “I know very little, but the legends…”

“In the aftermath of each one, mankind was broken. Great cities in ashes, industry smashed. Each time, knowledge and growth were reduced to an almost prehistoric state—it took centuries of rebuilding to restore civilization to what it had been before.” She hesitated. “I keep hoping that I’m wrong.”

“Urithiru,” Shallan said. She tried to refrain from just asking questions, trying instead to reason her way to the answer. “You said the city was a kind of base or home to the Knights Radiant. I hadn’t heard of it before speaking with you, and so can guess that it’s not commonly referred to in the literature. Perhaps, then, it is one of the things that the Hierocracy suppressed knowledge of?”

“Very good,” Jasnah said. “Although I think that it had begun to fade into legend even before then, the Hierocracy did not help.”

“So if it existed before the Hierocracy, and if the pathway to it was locked at the fall of the Radiants… then it might contain records that have not been touched by modern scholars. Unaltered, unchanged lore about the Voidbringers and Surgebinding.” Shallan shivered. “That’s why we’re really going to the Shattered Plains.”

Jasnah smiled through her fatigue. “Very good indeed. My time in the Palanaeum was very useful, but also in some ways disappointing. While I confirmed my suspicions about the parshmen, I also found that many of the great library’s records bore the same signs of tampering as others I’d read. This ‘cleansing’ of history, removing direct references to Urithiru or the Radiants because they were embarrassments to Vorinism—it’s infuriating. And people ask me why I am hostile to the church! I need primary sources. And then, there are stories—ones I dare to believe—claiming that Urithiru was holy and protected from the Voidbringers. Maybe that was wishful fancy, but I am not too much a scholar to hope that something like that might be true.”

“And the parshmen?”

“We will try to persuade the Alethi to rid themselves of those.”

“Not an easy task.”

“A nearly impossible one,” Jasnah said, standing. She began to pack her books away for the night, putting them in her waterproofed trunk. “Parshmen are such perfect slaves. Docile, obedient. Our society has become far too reliant upon them. The parshmen wouldn’t need to turn violent to throw us into chaos—though I’m certain that is what’s coming—they could simply walk away. It would cause an economic crisis.”

She closed the trunk after removing one volume, then turned back to Shallan. “Convincing everyone of what I say is beyond us without more evidence. Even if my brother listens, he doesn’t have the authority to force the highprinces to get rid of their parshmen. And, in all honesty, I fear my brother won’t be brave enough to risk the collapse expelling the parshmen might cause.”

“But if they turn on us, the collapse will come anyway.”

“Yes,” Jasnah said. “You know this, and I know it. My mother might believe it. But the risk of being wrong is so immense that… well, we will need evidence—overwhelming and irrefutable evidence. So we find the city. At all costs, we find that city.”

Shallan nodded.

“I did not want to lay all of this upon your shoulders, child,” Jasnah said, sitting back down. “However, I will admit that it is a relief to speak of these things to someone who doesn’t challenge me on every other point.”

“We’ll do it, Jasnah,” Shallan said. “We’ll travel to the Shattered Plains and we’ll find Urithiru. We’ll get the evidence and convince everyone to listen.”

“Ah, the optimism of youth,” Jasnah said. “That is nice to hear on occasion too.” She handed the book to Shallan. “Among the Knights Radiant, there was an order known as the Lightweavers. I know precious little about them, but of all the sources I’ve read, this one has the most information.”

Shallan took the volume eagerly. Words of Radiance, the title read. “Go,” Jasnah said. “Read.”

Shallan glanced at her.

“I will sleep,” Jasnah promised, a smile creeping to her lips. “And stop trying to mother me. I don’t even let Navani do that.”

Shallan sighed, nodding, and left Jasnah’s quarters. Pattern tagged along behind; he’d spent the entire conversation silent. As she entered her cabin, she found herself much heavier of heart than when she’d left it. She couldn’t banish the image of terror in Jasnah’s eyes. Jasnah Kholin shouldn’t fear anything, should she?

Shallan crawled onto her cot with the book she’d been given and the pouch of spheres. Part of her was eager to begin, but she was exhausted, her eyelids drooping. It really had gotten late. If she started the book now…

Perhaps better to get a good night’s sleep, then dig refreshed into a new day’s studies. She set the book on the small table beside her bed, curled up, and let the rocking of the boat coax her to sleep.

She awoke to screams, shouts, and smoke.

The familiar scraping of wood as a bridge slid into place. The stomping of feet in unison, first a flat sound on stone, then the ringing thump of boots on wood. The distant calls of scouts, shouting back the all-clear.

The sounds of a plateau run were familiar to Dalinar. Once, he had craved these sounds. He’d been impatient between runs, longing for the chance to strike down Parshendi with his Blade, to win wealth and recognition.

That Dalinar had been seeking to cover up his shame—the shame of lying slumped in a drunken stupor while his brother fought an assassin.

The setting of a plateau run was uniform: bare, jagged rocks, mostly the same dull color as the stone surface they sat on, broken only by the occasional cluster of closed rockbuds. Even those, as their name implied, could be mistaken for more rocks. There was nothing but more of the same from here where you stood, all the way out to the far horizon; and everything you’d brought with you, everything human, was dwarfed by the vastness of these endless, fractured plains and deadly chasms.

Over the years, this activity had become rote. Marching beneath that white sun like molten steel. Crossing gap after gap. Eventually, plateau runs had become less something to anticipate and more a dogged obligation. For Gavilar and glory, yes, but mainly because they—and the enemy— were here. This was what you did.

The scents of a plateau run were the scents of a great stillness: baked stone, dried crem, long-traveled winds.

Most recently, Dalinar was coming to detest plateau runs. They were a frivolity, a waste of life. They weren’t about fulfilling the Vengeance Pact, but about greed. Many gemhearts appeared on the near plateaus, convenient to reach. Those didn’t sate the Alethi. They had to reach farther, toward assaults that cost dearly.

Ahead, Highprince Aladar’s men fought on a plateau. They had arrived before Dalinar’s army, and the conflict told a familiar story. Men against Parshendi, fighting in a sinuous line, each army trying to shove the other back. The humans could field far more men than the Parshendi, but the Parshendi could reach plateaus faster and secure them quickly.

The scattered bodies of bridgemen on the staging plateau, leading up to the chasm, attested to the danger of charging an entrenched foe. Dalinar did not miss the dark expressions on his bodyguards’ faces as they surveyed the dead. Aladar, like most of the other highprinces, used Sadeas’s philosophy on bridge runs. Quick, brutal assaults that treated manpower as an expendable resource. It hadn’t always been this way. In the past, bridges had been carried by armored troops, but success bred imitation.

The warcamps needed a constant influx of cheap slaves to feed the monster. That meant a growing plague of slavers and bandits roaming the Unclaimed Hills, trading in flesh. Another thing I’ll have to change, Dalinar thought.

Aladar himself didn’t fight, but had instead set up a command center on an adjacent plateau. Dalinar pointed toward the flapping banner, and one of his large mechanical bridges rolled into place. Pulled by chulls and full of gears, levers, and cams, the bridges protected the men who worked them. They were also very slow. Dalinar waited with self-disciplined patience as the workers ratcheted the bridge down, spanning the chasm between this plateau and the one where Aladar’s banner flew.

Once the bridge was in position and locked, his bodyguard—led by one of Captain Kaladin’s darkeyed officers—trotted onto it, spears to shoulders. Dalinar had promised Kaladin his men would not have to fight except to defend him. Once they were across, Dalinar kicked Gallant into motion to cross to Aladar’s command plateau. Dalinar felt too light on the stallion’s back—the lack of Shardplate. In the many years since he’d obtained his suit, he’d never gone out onto a battlefield without it.

Today, however, he didn’t ride to battle—not truly. Behind him, Adolin’s own personal banner flew, and he led the bulk of Dalinar’s armies to assault the plateau where Aladar’s men already fought. Dalinar didn’t send any orders regarding how the assault should go. His son had been trained well, and he was ready to take battlefield command—with General Khal at his side, of course, for advice.

Yes, from now on, Adolin would lead the battles.

Dalinar would change the world.

He rode toward Aladar’s command tent. This was the first plateau run following his proclamation requiring the armies to work together. The fact that Aladar had come, as commanded, and Roion had not—even though the target plateau was closest to Roion’s warcamp—was a victory unto itself. A small encouragement, but Dalinar would take what he could get.

He found Highprince Aladar watching from a small pavilion set up on a secure, raised part of this plateau overlooking the battlefield. A perfect location for a command post. Aladar was a Shardbearer, though he commonly lent his Plate and Blade to one of his officers during battles, preferring to lead tactically from behind the battle lines. A practiced Shardbearer could mentally command a Blade to not dissolve when he let go of it, though—in an emergency—Aladar could summon it to himself, making it vanish from the hands of his officer in an eyeblink, then appear in his own hands ten heartbeats later. Loaning a Blade required a great deal of trust on both sides.

Dalinar dismounted. His horse, Gallant, glared at the groom who tried to take him, and Dalinar patted the horse on the neck. “He’ll be fine on his own, son,” he said to the groom. Most common grooms didn’t know what to do with one of the Ryshadium anyway.

Trailed by his bridgeman guards, Dalinar joined Aladar, who stood at the edge of the plateau, overseeing the battlefield ahead and just below. Slender and completely bald, the man had skin a darker tan than most Alethi. He stood with hands behind his back, and wore a sharp traditional uniform with a skirtlike takama, though he wore a modern jacket above it, cut to match the takama.

It was a style Dalinar had never seen before. Aladar also wore a thin mustache and a tuft of hair beneath his lip, again an unconventional choice. Aladar was powerful enough, and renowned enough, to make his own fashion—and he did so, often setting trends.

“Dalinar,” Aladar said, nodding to him. “I thought you weren’t going to fight on plateau runs any longer.”

“I’m not,” Dalinar said, nodding toward Adolin’s banner. There, soldiers streamed across Dalinar’s bridges to join the battle. The plateau was small enough that many of Aladar’s men had to withdraw to make way, something they were obviously all too eager to do.

“You almost lost this day,” Dalinar noted. “It is well that you had support.” Below, Dalinar’s troops restored order to the battlefield and pushed against the Parshendi.

“Perhaps,” Aladar said. “Yet in the past, I was victorious in one out of three assaults. Having support will mean I win a few more, certainly, but will also cost half my earnings. Assuming the king even assigns me any. I’m not convinced that I’ll be better off in the long run.”

“But this way, you lose fewer men,” Dalinar said. “And the total winnings for the entire army will rise. The honor of the—”

“Don’t talk to me about honor, Dalinar. I can’t pay my soldiers with honor, and I can’t use it to keep the other highprinces from snapping at my neck. Your plan favors the weakest among us and undercuts the successful.”

“Fine,” Dalinar snapped, “honor has no value to you. You will still obey, Aladar, because your king demands it. That is the only reason you need. You will do as told.”

“Or?” Aladar said.

“Ask Yenev.”

Aladar started as if slapped. Ten years back, Highprince Yenev had refused to accept the unification of Alethkar. At Gavilar’s order, Sadeas had dueled the man. And killed him.

“Threats?” Aladar asked.

“Yes.” Dalinar turned to look the shorter man in the eyes. “I’m done cajoling, Aladar. I’m done asking. When you disobey Elhokar, you mock my brother and what he stood for. I will have a unified kingdom.”

“Amusing,” Aladar said. “Good of you to mention Gavilar, as he didn’t bring the kingdom together with honor. He did it with knives in the back and soldiers on the field, cutting the heads off any who resisted. Are we back to that again, then? Such things don’t sound much like the fine words of your precious book.”

Dalinar ground his teeth, turning away to watch the battlefield. His first instinct was to tell Aladar he was an officer under Dalinar’s command, and take the man to task for his tone. Treat him like a recruit in need of correction.

But what if Aladar just ignored him? Would he force the man to obey? Dalinar didn’t have the troops for it.

He found himself annoyed—more at himself than at Aladar. He’d come on this plateau run not to fight, but to talk. To persuade. Navani was right. Dalinar needed more than brusque words and military commands to save this kingdom. He needed loyalty, not fear.

But storms take him, how? What persuading he’d done in life, he’d accomplished with a sword in hand and a fist to the face. Gavilar had always been the one with the right words, the one who could make people listen.

Dalinar had no business trying to be a politician.

Half the lads on that battlefield probably didn’t think they had any business being soldiers, at first, a part of him whispered. You don’t have the luxury of being bad at this. Don’t complain. Change.

“The Parshendi are pushing too hard,” Aladar said to his generals. “They want to shove us off the plateau. Tell the men to give a little and let the Parshendi lose their advantage of footing; that will let us surround them.”

The generals nodded, one calling out orders.

Dalinar narrowed his eyes at the battlefield, reading it. “No,” he said softly.

The general stopped giving orders. Aladar glanced at Dalinar.

“The Parshendi are preparing to pull back,” Dalinar said.

“They certainly don’t act like it.”

“They want some room to breathe,” Dalinar said, reading the swirl of combat below. “They nearly have the gemheart harvested. They will continue to push hard, but will break into a quick retreat around the chrysalis to buy time for the final harvesting. That’s what you’ll need to stop.”

The Parshendi surged forward.

“I took point on this run,” Aladar said. “By your own rules, I get final say over our tactics.”

“I observe only,” Dalinar said. “I’m not even commanding my own army today. You may choose your tactics, and I will not interfere.”

Aladar considered, then cursed softly. “Assume Dalinar is correct. Prepare the men for a withdrawal by the Parshendi. Send a strike team forward to secure the chrysalis, which should be almost opened up.”

The generals set up the new details, and messengers raced off with the tactical orders. Aladar and Dalinar watched, side by side, as the Parshendi shoved forward. That singing of theirs hovered over the battlefield.

Then they pulled back, careful as always to respectfully step over the bodies of the dead. Ready for this, the human troops rushed after. Led by Adolin in gleaming Plate, a strike force of fresh troops broke through the Parshendi line and reached the chrysalis. Other human troops poured through the gap they opened, shoving the Parshendi to the flanks, turning the Parshendi withdrawal into a tactical disaster.

In minutes, the Parshendi had abandoned the plateau, jumping away and fleeing.

“Damnation,” Aladar said softly. “I hate that you’re so good at this.”

Dalinar narrowed his eyes, noticing that some of the fleeing Parshendi stopped on a plateau a short distance from the battlefield. They lingered there, though much of their force continued on away.

Dalinar waved for one of Aladar’s servants to hand him a spyglass, then he raised it, focusing on that group. A figure stood at the edge of the plateau out there, a figure in glistening armor.

The Parshendi Shardbearer, he thought. The one from the battle at the Tower. He almost killed me.

Dalinar didn’t remember much from that encounter. He’d been beaten near senseless toward the end of it. This Shardbearer hadn’t participated in today’s battle. Why? Surely with a Shardbearer, they could have opened the chrysalis sooner.

Dalinar felt a disturbing pit inside of him. This one fact, the watching Shardbearer, changed his understanding of the battle entirely. He thought he’d been able to read what was going on. Now it occurred to him that the enemy’s tactics were more opaque than he’d assumed.

“Are some of them still out there?” Aladar asked. “Watching?”

Dalinar nodded, lowering his spyglass.

“Have they done that before in any battle you’ve fought?”

Dalinar shook his head.

Aladar mulled for a moment, then gave orders for his men on the plateau to remain alert, with scouts posted to watch for a surprise return of the Parshendi.

“Thank you,” Aladar added, grudgingly, turning to Dalinar. “Your advice proved helpful.”

“You trusted me when it came to tactics,” Dalinar said, turning to him. “Why not try trusting me in what is best for this kingdom?”

Aladar studied him. Behind, soldiers cheered their victory and Adolin ripped the gemheart free from the chrysalis. Others fanned out to watch for a return attack, but none came.

“I wish I could, Dalinar,” Aladar finally said. “But this isn’t about you. It’s about the other highprinces. Maybe I could trust you, but I’ll never trust them. You’re asking me to risk too much of myself. The others would do to me what Sadeas did to you on the Tower.”

“What if I can bring the others around? What if I can prove to you that they’re worthy of trust? What if I can change the direction of this kingdom, and this war? Will you follow me then?”

“No,” Aladar said. “I’m sorry.” He turned away, calling for his horse.

The trip back was miserable. They’d won the day, but Aladar kept his distance. How could Dalinar do so many things so right, yet still be unable to persuade men like Aladar? And what did it mean that the Parshendi were changing tactics on the battlefield, not committing their Shardbearer? Were they too afraid to lose their Shards?

When, at long last, Dalinar returned to his bunker in the warcamps— after seeing to his men and sending a report to the king—he found an unexpected letter waiting for him.

He sent for Navani to read him the words. Dalinar stood waiting in his private study, staring at the wall that had borne the strange glyphs. Those had been sanded away, the scratches hidden, but the pale patch of stone whispered.

Sixty-two days.

Sixty-two days to come up with an answer. Well, sixty now. Not much time to save a kingdom, to prepare for the worst. The ardents would condemn the prophecy as a prank at best, or blasphemous at worst. To foretell the future was forbidden. It was of the Voidbringers. Even games of chance were suspect, for they incited men to look for the secrets of what was to come.

He believed anyway. For he suspected his own hand had written those words.

Navani arrived and looked over the letter, then started reading aloud. It turned out to be from an old friend who was going to arrive soon on the Shattered Plains—and who might provide a solution to Dalinar’s problems.

Kaladin led the way down into the chasms, as was his right.

They used a rope ladder, as they had in Sadeas’s army. These ladders had been unsavory things, the ropes frayed and stained with moss, the planks battered by far too many highstorms. Kaladin had never lost a man because of those storming ladders, but he’d always worried.

This one was brand new. He knew that for a fact, as Rind the quartermaster had scratched his head at the request, and then had one built to Kaladin’s specifications. It was sturdy and well made, like Dalinar’s army itself.

Kaladin reached the bottom with a final hop. Syl floated down and landed on his shoulder as he held up a sphere to survey the chasm bottom. The single sapphire broam was worth more by itself than the entirety of his wages as a bridgeman.

In Sadeas’s army, the chasms had been a frequent destination for bridgemen. Kaladin still didn’t know if the purpose had been to scavenge every possible resource from the Shattered Plains, or if it had really been about finding something menial—and will-breaking—for bridgemen to do between runs.

The chasm bottom here, however, was untouched. There were no paths cut through the snarl of stormleavings on the ground, and there were no scratched messages or instructions in the lichen on the walls. Like the other chasms, this one opened up like a vase, wider at the bottom than at the cracked top—a result of waters rushing through during highstorms. The floor was relatively flat, smoothed by the hardened sediment of settling crem.

As he moved forward, Kaladin had to pick his way over all kinds of debris. Broken sticks and logs from trees blown in from across the Plains. Cracked rockbud shells. Countless tangles of dried vines, twisted through one another like discarded yarn.

And bodies, of course.

A lot of corpses ended up in the chasms. Whenever men lost their battle to seize a plateau, they had to retreat and leave their dead behind. Storms! Sadeas often left the corpses behind even if he won—and bridgemen he’d leave wounded, abandoned, even if they could have been saved.

After a highstorm, the dead ended up here, in the chasms. And since storms blew westward, toward the warcamps, the bodies washed in this direction. Kaladin found it hard to move without stepping on bones entwined in the accumulated foliage on the chasm floor.

He picked his way through as respectfully as he could as Rock reached the bottom behind him, uttering a quiet phrase in his native tongue. Kaladin couldn’t tell if it was a curse or a prayer. Syl moved from Kaladin’s shoulder, zipping into the air, then streaking in an arc to the ground. There, she formed into what he thought of as her true shape, that of a young woman with a simple dress that frayed to mist just below the knees. She perched on a branch and stared at a femur poking up through the moss.

She didn’t like violence. He wasn’t certain if, even now, she understood death. She spoke of it like a child trying to grasp something beyond her.

“What a mess,” Teft said as he reached the bottom. “Bah! This place hasn’t seen any kind of care at all.”

“It is a grave,” Rock said. “We walk in a grave.”

“All of the chasms are graves,” Teft said, his voice echoing in the dank confines. “This one’s just a messy grave.”

“Hard to find death that isn’t messy, Teft,” Kaladin said.

Teft grunted, then started to greet the new recruits as they reached the bottom. Moash and Skar were watching over Dalinar and his sons as they attended some lighteyed feast—something that Kaladin was glad to be able to avoid. Instead, he’d come with Teft down here.

They were joined by the forty bridgemen—two from each reorganized crew—that Teft was training with the hope that they’d make good sergeants for their own crews.

“Take a good look, lads,” Teft said to them. “This is where we come from. This is why some call us the order of bone. We’re not going to make you go through everything we did, and be glad! We could have been swept away by a highstorm at any moment. Now, with Dalinar Kholin’s stormwardens to guide us, we won’t have nearly as much risk—and we’ll be staying close to the exit just in case…”

Kaladin folded his arms, watching Teft instruct as Rock handed practice spears to the men. Teft himself carried no spear, and though he was shorter than the bridgemen who gathered around him—wearing simple soldiers’ uniforms—they seemed thoroughly intimidated.

What else did you expect? Kaladin thought. They’re bridgemen. A stiff breeze could quell them.

Still, Teft looked completely in control. Comfortably so. This was right. Something about it was just… right.

A swarm of small glowing orbs materialized around Kaladin’s head, spren the shape of golden spheres that darted this way and that. He started, looking at them. Gloryspren. Storms. He felt as if he hadn’t seen the like in years.

Syl zipped up into the air and joined them, giggling and spinning around Kaladin’s head. “Feeling proud of yourself?”

“Teft,” Kaladin said. “He’s a leader.”

“Of course he is. You gave him a rank, didn’t you?”

“No,” Kaladin said. “I didn’t give it to him. He claimed it. Come on. Let’s walk.”

She nodded, alighting in the air and settling down, her legs crossed at the knees as if she were primly seating herself in an invisible chair. She continued to hover there, moving exactly in step with him.

“Giving up all pretense of obeying natural laws again, I see,” he said.

“Natural laws?” Syl said, finding the concept amusing. “Laws are of men, Kaladin. Nature doesn’t have them!”

“If I toss something upward, it comes back down.”

“Except when it doesn’t.”

“It’s a law.”

“No,” Syl said, looking upward. “It’s more like… more like an agreement among friends.”

He looked at her, raising an eyebrow.

“We have to be consistent,” she said, leaning in conspiratorially. “Or we’ll break your brains.”

He snorted, walking around a clump of bones and sticks pierced by a spear. Cankered with rust, it looked like a monument.

“Oh, come on,” Syl said, tossing her hair. “That was worth at least a chuckle.”

Kaladin kept walking.

“A snort is not a chuckle,” Syl said. “I know this because I am intelligent and articulate. You should compliment me now.”

“Dalinar Kholin wants to refound the Knights Radiant.”

“Yes,” Syl said loftily, hanging in the corner of his vision. “A brilliant idea. I wish I’d thought of it.” She grinned triumphantly, then scowled.

“What?” he said, turning back to her.

“Has it ever struck you as unfair,” she said, “that spren cannot attract spren? I should really have had some gloryspren of my own there.”

“I have to protect Dalinar,” Kaladin said, ignoring her complaint. “Not just him, but his family, maybe the king himself. Even though I failed to keep someone from sneaking into Dalinar’s rooms.” He still couldn’t figure out how someone had managed to get in. Unless it hadn’t been a person. “Could a spren have made those glyphs on the wall?” Syl had carried a leaf once. She had some physical form, just not much.

“I don’t know,” she said, glancing to the side. “I’ve seen…”

“What?”

“Spren like red lightning,” Syl said softly. “Dangerous spren. Spren I haven’t seen before. I catch them in the distance, on occasion. Stormspren? Something dangerous is coming. About that, the glyphs are right.”

He chewed on that for a while, then finally stopped and looked at her. “Syl, are there others like me?”

Her face grew solemn. “Oh.”

“Oh?”

“Oh, that question.”

“You’ve been expecting it, then?”

“Yeah. Sort of.”

“So you’ve had plenty of time to think about a good answer,” Kaladin said, folding his arms and leaning back against a somewhat dry portion of the wall. “That makes me wonder if you’ve come up with a solid explanation or a solid lie.”

“Lie?” Syl said, aghast. “Kaladin! What do you think I am? A Cryptic?”

“And what is a Cryptic?”

Syl, still perched as if on a seat, sat up straight and cocked her head. “I actually… I actually have no idea. Huh.”

“Syl…”

“I’m serious, Kaladin! I don’t know. I don’t remember.” She grabbed her hair, one clump of white translucence in each hand, and pulled sideways.

He frowned, then pointed. “That…”

“I saw a woman do it in the market,” Syl said, yanking her hair to the sides again. “It means I’m frustrated. I think it’s supposed to hurt. So… ow? Anyway, it’s not that I don’t want to tell you what I know. I do! I just… I don’t know what I know.”

“That doesn’t make sense.”

“Well, imagine how frustrating it feels!”

Kaladin sighed, then continued along the chasm, passing pools of stagnant water clotted with debris. A scattering of enterprising rockbuds grew stunted along one chasm wall. They must not get much light down here.

He breathed in deeply the scents of overloaded life. Moss and mold. Most of the bodies here were mere bone, though he did steer clear of one patch of ground crawling with the red dots of rotspren. Just beside it, a group of frillblooms wafted their delicate fanlike fronds in the air, and those danced with green specks of lifespren. Life and death shook hands here in the chasms.

He explored several of the chasm’s branching paths. It felt odd to not know this area; he’d learned the chasms closest to Sadeas’s camp better than the camp itself. As he walked, the chasm grew deeper and the area opened up. He made a few marks on the wall.

Along one fork he found a round open area with little debris. He noted it, then walked back, marking the wall again before taking another branch. Eventually, they entered another place where the chasm opened up, widening into a roomy space.

“Coming here was dangerous,” Syl said.

“Into the chasms?” Kaladin asked. “There aren’t going to be any chasmfiends this close to the warcamps.”

“No. I meant for me, coming into this realm before I found you. It was dangerous.”

“Where were you before?”

“Another place. With lots of spren. I can’t remember well… it had lights in the air. Living lights.”

“Like lifespren.”

“Yes. And no. Coming here risked death. Without you, without a mind born of this realm, I couldn’t think. Alone, I was just another windspren.”

“But you’re not windspren,” Kaladin said, kneeling beside a large pool of water. “You’re honorspren.”

“Yes,” Syl said.

Kaladin closed his hand around his sphere, bringing near-darkness to the cavernous space. It was day above, but that crack of sky was distant, unreachable.

Mounds of flood-borne refuse fell into shadows that seemed almost to give them flesh again. Heaps of bones took on the semblance of limp arms, of corpses piled high. In a moment, Kaladin remembered it. Charging with a yell toward lines of Parshendi archers. His friends dying on barren plateaus, thrashing in their own blood.

The thunder of hooves on stone. The incongruous chanting of alien tongues. The cries of men both lighteyed and dark. A world that cared nothing for bridgemen. They were refuse. Sacrifices to be cast into the chasms and carried away by the cleansing floods.

This was their true home, these rents in the earth, these places lower than any other. As his eyes adjusted to the dimness, the memories of death receded, though he would never be free of them. He would forever bear those scars upon his memory like the many upon his flesh. Like the ones on his forehead.

The pool in front of him glowed a deep violet. He’d noticed it earlier, but in the light of his sphere it had been harder to see. Now, in the dimness, the pool could reveal its eerie radiance.

Syl landed on the side of the pool, looking like a woman standing on an ocean’s shore. Kaladin frowned, leaning down to inspect her more closely. She seemed… different. Had her face changed shape?

“There are others like you,” Syl whispered. “I do not know them, but I know that other spren are trying, in their own way, to reclaim what was lost.”

She looked to him, and her face now had its familiar form. The fleeting change had been so subtle, Kaladin wasn’t sure if he’d imagined it.

“I am the only honorspren who has come,” Syl said. “I…” She seemed to be stretching to remember. “I was forbidden. I came anyway. To find you.”

“You knew me?”

“No. But I knew I’d find you.” She smiled. “I spent the time with my cousins, searching.”

“The windspren.”

“Without the bond, I am basically one of them,” she said. “Though they don’t have the capacity to do what we do. And what we do is important. So important that I left everything, defying the Stormfather, to come. You saw him. In the storm.”

The hair stood up on Kaladin’s arms. He had indeed seen a being in the storm. A face as vast as the sky itself. Whatever the thing was—spren, Herald, or god—it had not tempered its storms for Kaladin during that day he’d spent strung up.

“We are needed, Kaladin,” Syl said softly. She waved for him, and he lowered his hand to the shore of the tiny violet ocean glowing softly in the chasm. She stepped onto his hand, and he stood up, lifting her.

She walked up his fingers and he could actually feel a little weight, which was unusual. He turned his hand as she stepped up until she was perched on one finger, her hands clasped behind her back, meeting his eyes as he held that finger up before his face.

“You,” Syl said. “You’re going to need to become what Dalinar Kholin is looking for. Don’t let him search in vain.”

“They’ll take it from me, Syl,” Kaladin whispered. “They’ll find a way to take you from me.”

“That’s foolishness. You know that it is.”

“I know it is, but I feel it isn’t. They broke me, Syl. I’m not what you think I am. I’m no Radiant.”

“That’s not what I saw,” Syl said. “On the battlefield after Sadeas’s betrayal, when men were trapped, abandoned. That day I saw a hero.”

He looked into her eyes. She had pupils, though they were created only from the differing shades of white and blue, like the rest of her. She glowed more softly than the weakest of spheres, but it was enough to light his finger. She smiled, seeming utterly confident in him.

At least one of them was.

“I’ll try,” Kaladin whispered. A promise.

“Kaladin?” The voice was Rock’s, with his distinctive Horneater accent. He pronounced the name “kal-ah-deen,” instead of the normal “kal-a-din.”

Syl zipped off Kaladin’s finger, becoming a ribbon of light and flitting over to Rock. He showed respect to her in his Horneater way, touching his shoulders in turn with one hand, and then raising the hand to his forehead. She giggled; her profound solemnity had become girlish joy in moments. Syl might only be a cousin to windspren, but she obviously shared their impish nature.

“Hey,” Kaladin said, nodding to Rock, and fishing in the pool. He came out with an amethyst broam and held it up. Somewhere up there on the Plains, a lighteyes had died with this in his pocket. “Riches, if we still were bridgemen.”

“We are still bridgemen,” Rock said, coming over. He plucked the sphere from Kaladin’s fingers. “And this is still riches. Ha! Spices they have for us to requisition are tuma’alki! I have promised I will not fix dung for the men, but it is hard, with soldiers being accustomed to food that is not much better.” He held up the sphere. “I will use him to buy better, eh?”

“Sure,” Kaladin said. Syl landed on Rock’s shoulder and became a young woman, then sat down.

Rock eyed her and tried to bow to his own shoulder.

“Stop tormenting him, Syl,” Kaladin said.

“It’s so fun!”

“You are to be praised for your aid of us, mafah’liki,” Rock said to her. “I will endure whatever you wish of me. And now that I am free, I can create a shrine fitting to you.”

“A shrine?” Syl said, eyes widening. “Ooooh.”

“Syl!” Kaladin said. “Stop it. Rock, I saw a good place for the men to practice. It’s back a couple of branches. I marked it on the walls.”

“Yes, we saw this thing,” Rock said. “Teft has led the men there. It is strange. This place is frightening; it is a place that nobody comes, and yet the new recruits…”

“They’re opening up,” Kaladin guessed.

“Yes. How did you know this thing would happen?”

“They were there,” Kaladin said, “in Sadeas’s warcamp, when we were assigned to exclusive duty in the chasms. They saw what we did, and have heard stories of our training here. By bringing them down here, we’re inviting them in, like an initiation.”

Teft had been having problems getting the former bridgemen to show interest in his training. The old soldier was always sputtering at them in annoyance. They’d insisted on remaining with Kaladin rather than going free, so why wouldn’t they learn?

They had needed to be invited. Not just with words.

“Yes, well,” Rock said. “Sigzil sent me. He wishes to know if you are ready to practice your abilities.”

Kaladin took a deep breath, glancing at Syl, then nodded. “Yes. Bring him. We can do it here.”

“Ha! Finally. I will fetch him.”

Words of Radiance © Brandon Sanderson, 2014

Join the discussion on our Words of Radiance spoiler thread!