Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn, while sometimes categorized as YA, is generally hailed as a story for all ages. As much as I love the book, I didn’t read it until I was in college, so my initial introduction into Beagle’s world (like many fans my age, I suspect) came courtesy of the 1982 Rankin/Bass animated movie of the same name.

While I can’t speak to the experience of reading the novel as a child, I certainly believe that a story as beautifully crafted and enduring as this one will resonate with readers of various ages and experience. I’d argue that the movie also has plenty to recommend it to adult fantasy fans, and is far more advanced in its themes than the vast majority of animated children’s entertainment. And while it stays very true to the book in many ways, the film manages to foreground certain elements of the original story that give it a very powerful, very unique appeal for children. Don’t get me wrong: it’s kind of a strange film, but therein lies its magic. It speaks to younger viewers in a manner that very few films ever do.

So, full disclosure: when I was about four, somewhere between my Extreme Wizard of Oz phase and the beginning of my All Labyrinth, All the Time mania, I discovered The Last Unicorn and the rest of the world ceased to exist. To my mother’s understandable chagrin, I decided that I only ever wanted to wear pure white clothing (a perfect plan for an active four-year-old, obviously), and I switched my entire career path from “witch” over to “unicorn.” It…probably made sense at the time. The fact that there isn’t any surviving photographic evidence of this period in my life should just be chalked up to some kind of crazy miracle and never questioned, because yikes. It was bad.

Which is all to say that yes, my nostalgia for this movie is both longstanding and intense; it’s a film that’s stuck with me—I’ve watched it countless times over the years and bonded over it with high school friends and college roommates and even now with current coworkers. I know it’s not for everybody, and I wouldn’t expect someone who didn’t grow up with The Last Unicorn to have the same reaction to it as those who did. I don’t know if I’d feel such a strong connection to the movie if I saw it for the first time now, in my thirties—but looking back, it’s illuminating to delve into the reasons why it holds such a strong allure, particularly for younger viewers, and why it made such a powerful impact on me and so many other kids over the years.

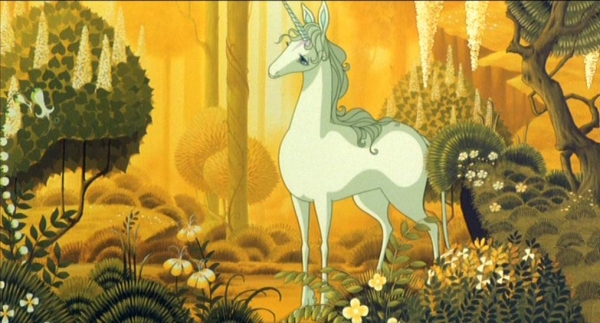

Beginning on the most basic level, of course, there’s the look of the film: Rankin and Bass hired the Japanese studio Topcraft to provide the design work and animation for The Last Unicorn. Topcraft had produced hand-drawn animation for a number of Rankin/Bass titles in the seventies and early eighties (including The Hobbit and ThunderCats), and Topcraft artists would become the core of Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli in 1985 following the success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

From the gorgeous, sun-dappled forest of the opening scene, with its deep shadows and rays of light glinting through the trees to the spectacular opening credits sequence, based on the famed Unicorn Tapestries, the movie thoroughly captures the otherworldly beauty of the unicorn and her enchanted wood and the rough strangeness of the world beyond. The human characters look a bit awkward, ungainly, and almost stunted in comparison to the unicorn’s shimmering grace, as they should—it is, after all, her story.

The unicorn is voiced by Mia Farrow, heading up a stellar cast, and it’s remarkable how Farrow’s distinctive qualities as an actress come through so strongly in her voice—tremulous and almost girlish, but tempered with an impressive urgency and self-possession. Alan Arkin is an interesting choice for Schmendrick—Beagle complained that his performance was “flat,” and I can see that: in the book, the magician comes off as more mercurial than neurotic, but he also has a more substantial backstory and a bit more to do in the original version. Personally, I enjoy Arkin’s take on the character: earnest, self-deprecating, and occasionally sarcastic, with an easy, believable chemistry between Schmendrick and Molly Grue (brought to life with humor and passion by Tammy Grimes’ distinctive voicework).

Angela Lansbury seems to have a fantastic time playing the shabby witch Mommy Fortuna, shouting threats and cackling madly (I admittedly love Lansbury in anything, but especially as a villain or antagonist). Christopher Lee is absolutely brilliant as the tormented King Haggard—I’m just as awed by his performance today as I was when I was four, if not more so. His Haggard is so intense, and rather frightening—but just as in the book, he never comes off as an actual villain, but rather as tortured, unhappy, misguided to the point of madness. Jeff Bridges is appealingly sincere and boyish as Haggard’s adopted son, Prince Lír, although admittedly it can sometimes be a little odd rewatching the film in a post-Lebowski world and thinking, “The Dude is full-on singing a love song to a unicorn lady right now.” Well, technically, it’s a duet—and while neither Farrow or Bridges have the crazy range of an Idina Menzel, for example, their voices are pleasant and there’s a certain halting awkwardness that genuinely fits the characters and their tentative steps toward romance.

The rest of the characters are voiced by a collection of character actors and Rankin/Bass regulars: Paul Frees, Don Messick, Keenan Wynn, René Auberjonois, etc, and the mixture of British and American actors and accents has always struck me as rather interesting. The decision to include a diverse array of dialects (and not conform to the time-honored “fantasy accents are always vaguely British” model) certainly helps reinforce the book’s playful approach to its setting in time and place, blending together quasi-medieval trappings and modern slang and references (also reflected in the dialogue throughout the film).

On a similar note, the original score composed for the film by Jimmy Webb adds to this sense of displacement and strangeness, filled with an eloquent sense of longing, soaring orchestration and strains of rich melodic melancholy. The folk rock band America perform several of Webb’s original songs (in addition to one song sung by Mia Farrow, plus the aforementioned duet between Farrow and Bridges)—it might not be to everyone’s taste, but as a kid who grew up on plenty of folk and classic rock (hell, I still think “A Horse With No Name” and “Sister Golden Hair” are pretty great), I’ve always found the soundtrack to be haunting and rather beautiful, and so different from the usual kids movie musical fare.

Then again, “deviating from stereotypical kids movie fare” pretty much describes most aspects of The Last Unicorn. Beagle himself wrote the screenplay, and was able to keep the original story—which I’ve summarized in detail in an earlier post—largely intact, with the exception of a few plot points. I’ve already mentioned Schmendrick’s backstory (in the book, he’s cursed with immortality until he can learn to be a great magician), and we also lose the interactions with townsfolk along the road to Haggard’s castle; Hagsgate is cut out entirely, along with the witch’s curse and Lír s origin story.

I’d also argue that some of the book’s humor doesn’t entirely translate, or comes off as more odd than funny on occasion. Scenes like the amorous talking tree that takes a shine to Schmendrick, or the initial interview with the kooky reanimated skeleton guarding the entrance to the Red Bull’s lair strike me as more menacing than was intended in spite of (or possible because of?) the attempt at lighthearted, wackity-schmackity musical cues. It’s really just a matter of tone—having read the book, I watch these scenes a little differently now then I did as a kid, when I just accepted the weirdness and rolled with it (a strategy I’d still heartily recommend to first-time viewers).

By necessity, the movie is more focused on the action, less generous with its asides and commentary, and the metafictional cleverness is toned down (though not lost entirely). The book weaves a story that frequently doubles in on itself and riffs brilliantly on the nature of stories and storytelling, while the film really drives home the personal experience of the unicorn and the changes she undergoes throughout her journey. I don’t mean to imply that her experience isn’t central to the novel—of course it is—but the book dwells on details about the unicorn (her great age, her inscrutable immortal nature, her knowledge of and reactions to the other beings that she encounters) that repeatedly set her at a certain distance. The reader understands from the first that the unicorn is, as an immortal, essentially enigmatic and alien, and that mortal beings are not meant to identify with her too directly.

In the movie, on the other hand, I’d argue that the audience, and particularly children, are able to relate to the unicorn and her plight from the first, precisely because of her isolation and the confusion she experiences. We are part of her world from the beginning, and rather than taking pains to tells us that the unicorn is something strange and ancient and unknowable, Farrow’s expressive performance draws us in…but the character retains a strangeness and a separateness that actually becomes a point of connection for small children, rather than distancing them.

The appeal of the unicorn—this particular unicorn—goes far beyond the realm of the sparkly neon flood of unicorn-laden imagery unleashed on young girls starting in the early 80s in the form of Lisa Frank Trapper Keepers and My Little Pony merchandise. She is aesthetically beautiful, yes—but not a cuddly object of adoration or a kind of spiritual power animal boldly trampling rainbows and frolicking somewhat inexplicably through the Milky Way (not that there’s necessarily anything wrong with that). It’s just that this unicorn is not particularly happy or at ease at the start of her quest; in fact, she encounters reality much in the same way a young child might, making her way through a world that often seems strange, frightening, or hostile. She is self-contained but not unaware of (or immune to) the confusing and complex emotions of the people around her, with their esoteric and unfathomable moods, worries, disappointments, and self-delusions.

The mortals she encounters have drives and desires she simply doesn’t understand; they are preoccupied with their own mortality, with control over forces more powerful than themselves. There’s Haggard, obviously, with his obsessive need to possess unicorns, but also Mommy Fortuna’s fixation on the harpy as a deranged bid for immortality, or Captain Cully’s preoccupation with his own legend living on in song and story. Even her allies Schmendrick, Molly, and Lír are all arguably damaged (or at best, significantly unhappy or unfulfilled) in ways that even her magic can’t simply fix, and in knowing them and caring for them she inevitably comes to feel some of their sorrow, and learns the nature of regret—not that this empathy is seen as a bad thing in any way, but the story makes it very clear that friendship and other relationships can have emotional costs as well as rewards.

In some ways, it might be said that a young child is not all that different from an immortal creature, in his or her own mind. For a time, a child lives in her own world upon which other people, helpful or not, impede and intrude and expand and draw her out. When J.M. Barrie wrote “It is only the gay and innocent and heartless that can fly,” he captured the essence of childhood as a self-contained kingdom where the whims and wants and needs of others hold no dominion—a state rather similar to the unicorn’s untroubled existence in the lilac wood, before she learns that other unicorns have disappeared and feels compelled to go find them. The longer she spends in that world, entangled in obligations and the feelings and desires of others, the more of her innocence and heartlessness are worn away—and once she is turned into a mortal woman she is haunted by troubling dreams and memories where before there was a peaceful, uncomplicated emptiness.

The song that Farrow sings as the dream-haunted Lady Amalthea (“Now That I’m a Woman”) lends itself very well to a reading of The Last Unicorn as a story about moving from girlhood into adulthood, falling in love, and moving on, and I suppose that works, but it seems a little pat to me. This movie isn’t a simple love story, although that’s an aspect of it; I’d argue that it’s more about the gradual, sometimes painful, move away from the safety of a more isolated existence and toward empathy and socialization and obligations to other people—growing up, in other words. It’s a process that begins but doesn’t end in childhood, as the world and the people we meet change us in a million unexpected ways, for better or worse. And what I love about this movie is that it’s so honest about the fact that losing this sense of separateness is scary, and that it’s possible to move past pain and fear, but not to pretend that they don’t exist.

Even more impressive is that the movie isn’t interested in wrapping everything up in some hackneyed moral lesson at the end but in simply sharing a bit of wisdom, and reassurance that sacrificing the comfortable, insulated boundaries of your solitude can be worth the cost. Personally, I distrusted a preachy, hamfisted moral more than anything as a kid—I’ve never been a big fan of the smug and oversimplified approach to getting a point across (looking at you, Goofus & Gallant, my old nemeses…shakes fist). The Last Unicorn never talks down to its audience—it doesn’t tack on a speech at the end about how if you trust in the power of friendship and eat your vegetables, true love will magically conquer all. It’s a movie that’s very much about regret, as evinced by the final exchange between the unicorn and Schmendrick:

“I’m a little afraid to go home. I’ve been mortal, and some part of me is mortal yet; I am no longer like the others, for no unicorn was ever born who could regret, but now I do—I regret.”

“I am sorry I have done you evil and I cannot undo it…”

“No—unicorns are in the world again. No sorrow will live in me as long as that joy, save one—and I thank you for that part, too.”

There’s a note of melancholy here that is characteristic of the movie as a whole, and that tone is also part of the film’s fascination for young viewers, as children too young to know much of sorrow or regret encounter these emotions along with the character. The film’s beauty is inextricable from its more solemn depths, which can awaken in children a kind of wistfulness not fully understood, but deeply felt. It tells kids, in the gentlest and most reassuring possible way that one day they may have to relinquish their position at the center of their own small world and adapt to the chaos of a larger, louder, more random existence, in which the needs and expectations of others will become inextricably tangled up with your own. Things will be complicated and confusing and sometimes contradictory—and you will be okay, and you won’t be alone.

There are a million stories that paint black-and-white heroes and villains in cheery Technicolor tones, and promise a Happily Ever After to ease every ending. Some are great, and some are not, and the success of these tales is almost all in the quality of the telling; The Last Unicorn is not like any of these stories—it doesn’t look or sound or behave quite like anything else. Even if it weren’t so beautiful, or so beautifully told, it would still have the distinction of saying something to its audience that truly needs to be said, something useful and real and comforting. Something I’ll never get tired of hearing.

Bridget McGovern is the managing editor of Tor.com, which is a pretty great thing to be, if you can’t be a unicorn. So it all kinda worked out, eventually.