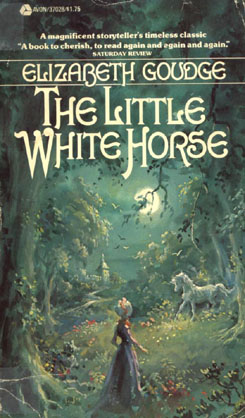

Elizabeth Goudge needed at least a temporary escape from the horrors of World War II when she sat down to write The Little White Horse. Set in a land and time that seems remote from war, where food rationing has never been heard of (the lavish descriptions of rich, sweet foods are among the most memorable parts of the book), the book certainly succeeded as an escape: an idealistic fantasy—with just a touch of realism—that assured readers that with faith, everything could work out. Really.

Maria Merryweather is only thirteen when she finds herself orphaned and almost destitute in London—almost, since, luckily enough, it turns out that she has a cousin in the West Country, Sir Benjamin Merryweather, who is more than willing to welcome her and her governess, Miss Heliotrope, to his ancestral estate of Moonacre, despite his general dislike of women. (He suffered, it seems, a Grave Disappointment in, not quite his youth, but his middle age.) She also gets to bring along her dog, Wiggins. I’ll give you author Elizabeth Goudge’s masterful description:

But though Wiggins’s moral character left much to be desired, it must not be thought that he was a useless member of society, for a thing of beauty is a joy for ever, and Wiggins’s beauty was of that high order than can only be described by that tremendous trumpet-sounding word ‘incomparable.’

Wiggins was aware that excessive emotion is damaging to personal beauty, and he never indulged in it…Except, perhaps, a very little, in regard to food. Good food did make him feel emotional.

The description of their journey there has more than a touch of the Gothic about it: the orphan, the lonely journey, the bad roads, the odd castle that rarely receives visitors, where people are initially reluctant to speak about the past, the strange servants. But the second Maria reaches the house, she slips from Gothic to fairy tale.

The house, after all, is magical—or almost magical, which is just about the same thing, what with its tiny doors and astonishing food seemingly arriving from nowhere (actually from the genius hands of that kitchen artist, Marmaduke Scarlet), the way all of the animals truly magically get along, the way that Maria finds that if she just trusts Moonacre to tell her its secrets when it will, everything will work out right. And the way that nobody in the book ever explains how the furniture got through the tiny doors—sure, some of the doors are normal sized, but the tiny ones for some of the rooms? And the way that her clothing has been carefully laid out for her—clothing that also tells her more or less what she will be doing that day: dresses for quiet days, a habit for pony riding days. Also, cookies left in her room for when she needs a snack. All happening because, as it turns out—also in classic fairy tale style—Maria is a Moon Princess.

(I must say that with all of the constant eating—Maria never misses a meal or a snack in this entire book—I couldn’t help wondering just how long Maria would continue to be able to get through these tiny doors, even with all of her running, climbing, horseback riding, and walking with lions. But I digress.)

And then, of course, there are all of the wonderful companions Maria meets, quite like the magical helpers in classic fairy tales: the amazingly gifted, focused and very short cook Marmaduke Scarlet; the Old Parson, filled with tales of the past, who may or may not have a Mysterious Connection with Miss Heliotrope; Wrolf, who may or may not be a dog; Zachariah, a most remarkable cat (he’s able to draw and sort of write with his paws); Serena, a hare; Loveday, who was once a Moon Princess; and her son Robin, a boy about Maria’s age, who once played with her in London. Well. Kinda. Let’s just say Maria is convinced he did, and this is, after all, a book about magic.

(You will notice that I left Wiggins off the list of helpers. This is because, although he is very definitely in most of the book and does a lot of eating, I don’t think that most readers would call him helpful.)

But for all that, A Little White Horse also takes some, shall we say, significant liberties with fairy tale tropes. For one, Maria is not a classic beauty, or even particularly beautiful at all, even though she is a Moon Princess, and she is vain about her clothing and certain parts of her body. (She never does lose this vanity, either.) For two, although Maria’s quest does involve finding a treasure—a classic fairy tale bit—where she finds it is not at all a classic place, and she does not find it gain a treasure or prove her worthiness or heal someone sick, but rather to prove something about the past.

In part this is because, as it turns out, the villains of the piece are not actually the real villains. The actual villains are something more subtle: bad tempers, holding grudges, not making amends for wrongs. And so, Maria’s goal quest is less to defeat the supposed villains, and more to bargain with them—and learning to overcome significant character flaws along the way. (She doesn’t manage to overcome all of them—it’s not that much of a fairy tale.)

For three, she doesn’t marry a prince. Indeed, pretty much nobody in this story ends up marrying within their social class, although Loveday was at one point at least closer to Sir Benjamin’s social class. Until, that is, she ran away and married an attorney and became a housekeeper. Miss Heliotrope, the daughter of a not exactly wealthy village rector, falls in love with a French marquis—although when they do eventually marry, that title has been left well behind. And Maria, the proud Moon Princess, marries a shepherd boy. Though since Robin can visit Maria in his dreams, that’s perhaps not that surprising.

For that matter, very few people stay within their social class, a rather surprising situation for a novel set on an early 19th century estate—the time of Jane Austen. The French marquis loses his wealth and eventually becomes a poor country parson; the poachers become respectable fishermen and traders; Miss Heliotrope leaves her father’s home to become a governess; and Maria, in a rather dizzying turn of events, goes from wealth to poverty to wealth again. Only Sir Benjamin, the lord of the estate, and his main servant Marmaduke Scarlet, retain their original positions.

And there’s a larger, and I think fairly significant change to the fairy tale structure in the end. Fairy tales frequently deal with issues of pain and loss, and in this, The Little White Horse is no exception, with nearly every character (except, again, Marmaduke Scarlet, who is just an outlier everywhere here) having suffered loss and pain. But after the book starts, Maria does not have something taken from her. Rather, she chooses to give something up—and persuades Sir Benjamin to give up something as well. Well, to be fair, “persuades” is not quite the right word here: she demands, and Sir Benjamin agrees.

And, where many traditional fairy tales end with the hero or heroine gaining a kingdom—or at least marrying into one, in this case, to gain her happy ending, Maria has to give away part of her kingdom. Spoiler: it all works out.

And, like the best of fairy tales, it has a few flaws that might disturb readers. One is Maria’s statement that she will marry Robin—this because Maria is only thirteen when she says this, and has not exactly had a huge opportunity to marry other people. It doesn’t exactly help that the book states that they marry about a year later, when Maria is fourteen and Robin about the same age, perhaps a couple of years older. That may have been an error on the writer’s part, and in any case, Maria sometimes seems a bit older than her actual age, and the marriage is an extremely happy one, with plenty of children.

The second is a scene where Maria is chided for being overly curious—going along with some other not very subtle women-bashing in the book. To counter this, however, the book’s general theme seems to be less against curiosity, and more for faith. And for all of the women-bashing at the beginning of the book (and there’s quite a bit of it), notably, at the end, the estate and the village are saved not by a man, but by a girl, and Maria, not a boy, is able to inherit and rule the estate in her own right.

The third is the constant description of the villains of the piece as Black Men. Goudge means to say just that they have black hair and wear black clothing, not that they have black skin, but to be honest, that’s not what I immediately thought when I first saw the term in this book.

And, bluntly, this book may be a bit too sugary for many readers.

By listing all this, I’ve probably said too much, or too little. All I can finally say is, this has been one of my comfort reads since I first picked it up, so many years ago, and it remains one of my comfort reads today. If you need something sweet and silvery, something where everything works out just the way it really should, and where everyone gets to eat a lot of wonderful food, this is your book.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Modern editions have renamed the Black Men so that they are now Men From The Dark Woods: which is somewhat cumbersome every time they are mentioned, but one sees why. The really striking thing, though, is that there are no Women From The Dark Woods; the men all live together in a castle, but it’s not at all clear how they got there – though their leader, at least, certainly has an ancestry.

It should be said that the reason Maria and Robin’s marriage is delayed is that their guardians put their foot down and insist that thirteen is too young, and they must wait a year. I think I just accepted this as an example of the odd things people did in the olden days.

Salmon pink geraniums! Never did like them myself.

I haven’t read this book in years, partly because of the faith overtones and partly because along with all of the other childhood books I still possess it has been boxed up waiting for shelves. It would still be a comfort read though, far more so than say the Island books. The appropriate for the day clothes, the freedom Maria is given and the huge amount of delicious sounding food were all very appealing to me as a child. Even for the time it is set fifteen would be young to marry wouldn’t it? I certainly thought so when I first read it at an age when the attractions of marriage were not entirely obvious and all too often it seemed to mean the end of all the fun!

Even 150 years ago, marriage as young as fifteen was not unheard of. At the time of writing, a wedding at fourteen would have been uncommon among the gentry, but it was certainly not unusual in the lower classes.

So much of my childhood reading was set in this kind of England that when I read about Black Men in books I tend to picture dark haired English/Irish types. My literary race signifiers are still poorly set for modern writing.

this has been one of my comfort reads since I first picked it up, so many years ago, and it remains one of my comfort reads today.

Yes, Yes, Yes.

I’d be interested in your take on Linnets and Valerians – are you going to do that one?

I loved this book when I was younger! I so wanted that tower room with dark blue and silver stars and a door that no one else was small enough to get through.

(and I always thought that Bejamin and Loveday’s relationship had a certain touch of Beauty and the Beast that takes a lot longer to resolve for them than the original)

For one, Maria is not a classic beauty, or even particularly beautiful

at all, even though she is a Moon Princess, and she is vain about her

clothing and certain parts of her body.

She has a nice nose? Oh, wait. Wrong series.

I haven’t read the book yet, but since watching the 2009 film Moonacre it has been on my radar. Your thoughts on the book and the comments above have raised it significantly on my to-read list. Thanks:)

@AnotherAndrew and @mary2 – Yep, their marriage is delayed a year, so they are married at fourteen. It’s not unquestionable for the time, but I should also note that many 19th century books make it clear that their authors think that getting married at 16 and 17 is too young, and a look at family records in the 19th century show that most women in all social classes did marry later than that, with quite a few waiting until their 20s or even 30s to marry – which to be honest, given that these are often the same books gasping ack, ack, the girl has to get married and gives the sense that if you aren’t married by 21 it’s ALL OVER, surprised me.

Interestingly enough, records suggest that marrying young was more common among aristocrats than among the lower classes, though three were certainly exceptions in both directions.

Anyway, this book is not really trying to create an accurate depiction of 19th century social life and weddings, and Maria and Robin are very obviously getting married, so I think it’s ok.

@bethmitcham – The text is going for dark haired English/Irish, but it does read a bit differently to me.

@Tehanu – Added to the list, but there will be a bit of an interruption while we briefly tackle Eleanor Cameron. (And if my calendar is correct the summer movie schedule means that Lois Lowry is up fairly soon as well.)

@LKBurwell – There’s definitely quite a bit of East ‘O the Sun/West ‘O the Moon in the text, which is a different version of the Beauty and the Beast fairy tale, so I think you’re on a correct path here.

@Bayushi – Hee.

@GaranS – I still haven’t seen Moonacre yet – I keep meaning to, and then keep getting worried that it will ruin my memories of this book. Maybe someday :)

As I understand it, Moonacre is very different from the book – it is Fantasy all over, whereas in the book, though there is magic, it is kept gentle and in the background. So I think it would probably be quite easy to keep them disentangled.

Being on a Kage Baker kick, I just re-read The Hotel Under the Sand, which is strongly reminding me of this book.

Oh, yes, I loved this book when I was small. I’ve reread it a few times as an adult, but not recently, so it’s good to see it here!

@LKBurwell, I agree about Maria’s room. It was the very favorite and most magical part of this book for me. It’s got to be one of the best girl’s rooms in all children’s literature. Though Jill’s room in Cair Paravel in The Silver Chair is pretty wonderful, too, evoked with just a few concrete elements, a view and a feeling of adventure.

“(I must say that with all of the constant eating—Maria never misses a meal or a snack in this entire book—I couldn’t help wondering just how long Maria would continue to be able to get through these tiny doors, even with all of her running, climbing, horseback riding, and walking with lions. But I digress.)”

Oh, but don’t you remember the part where Maria looks at what Sir Benjamin is eating and at his girth, and he reassures her that the Moon Merriweathers can eat anything and they still say slender?

I never thought of the Black Men as being anything racial. Are the same people who bowdlerized that changing Edward, the Black Prince to Edward, the Prince Who Wore Black Armor? Seriously, people, get a sense of history.