Grady Hendrix, author of Horrorstör, and Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction are digging deep inside the Jack o’Lantern of Literature to discover the best (and worst) horror paperbacks. Are you strong enough to read THE BLOODY BOOKS OF HALLOWEEN???

Isn’t autumn the most nostalgic, the most contemplative of seasons? Something about the cooling weather and changing leaves, as well as the nearing of year’s end, causes one’s mind to look back. When I lived in the South I was often disappointed by the brief fall season, and found myself aching to recapture the excitement of awaiting Halloween.

To what could I turn to give myself a feeling of autumn? What could provide the scent of burning leaves, apple cider, pumpkin spice, the early darks and the bone-white moons, the chilled air that nuzzles your neck, the growing thrill of the arrival of All Hallow’s Eve and the macabre treats upon which to feast…? You guessed it: Ray Bradury’s collection of poisoned confections entitled The October Country.

There are few other people who can write with authority about this season and Halloween and their hold on our imaginations than the iconic and legendary Bradbury. Long a chronicler of the childhood sense of wonder and fear, myth and mystery, Bradbury’s boundless delight in all things fantastical, innocent, macabre, magical, and ancient is virtually unmatched in American literature. His books Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962) and The Halloween Tree (1972) are also timeless testaments to this wondrous time of year.

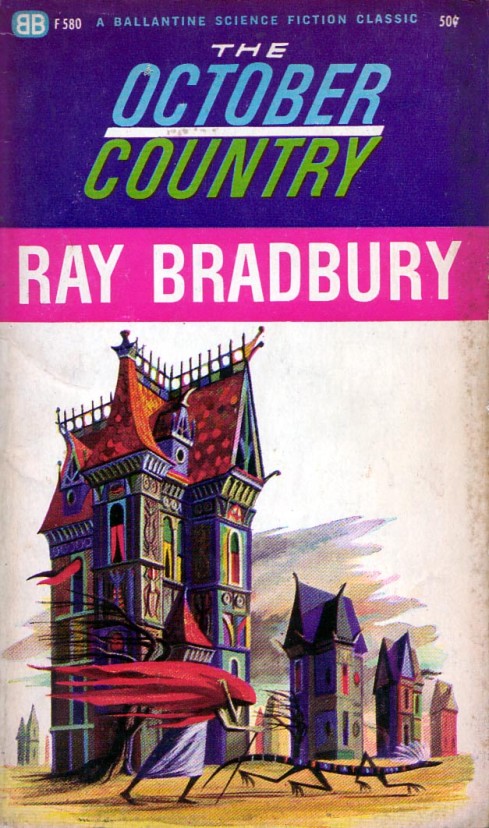

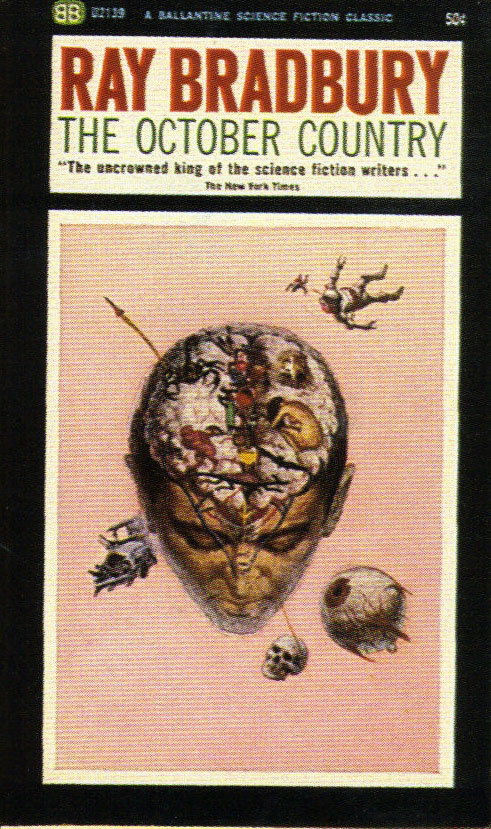

A quick history of October Country: in 1947, the esteemed Arkham House published Dark Carnival, Bradbury’s debut book, consisting mainly of his stories written for the classic pulp magazine Weird Tales. In 1955 Ballantine Books reprinted the collection, subtracting some of the stories and adding a few others, under the title The October Country. What we have here are 19 of Ray Bradbury’s earliest works. Does that mean that they’re unformed, not quite ready for consumption, perhaps timid things unsure of their footing before Bradbury gained confidence and experience as a writer? Oh, not at all! These stories are, in a word, amazing. Classic. Essential. Eternal.

One of my very favorites is “The Next in Line,” the longest story included. In it are the seeds of Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, Stephen King, Ramsey Campbell, Dennis Etchison, and others who would come along in the future to join Bradbury in delighting readers with dread. A young couple vacationing in Mexico visit the mummies in the catacombs and learn how the poor bury their dead. Marie, the wife, is struck dumb and cold by the dried-husk bodies:

One of my very favorites is “The Next in Line,” the longest story included. In it are the seeds of Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, Stephen King, Ramsey Campbell, Dennis Etchison, and others who would come along in the future to join Bradbury in delighting readers with dread. A young couple vacationing in Mexico visit the mummies in the catacombs and learn how the poor bury their dead. Marie, the wife, is struck dumb and cold by the dried-husk bodies:

“Jaws down, tongues out like jeering children, eyes pale brown-irised in upclenched sockets. Hairs, waxed and prickled by sunlight, each sharps as quills embedded on the lips, the cheeks, the eyelids, the brows. Little beards on chins and bosoms and loins. Flesh like drumheads and manuscripts and crisp bread dough. The women, huge ill-shaped tallow things, death-melted. The insane hair of them, like nests made and remade…”

You can see how Bradbury’s unmistakable style was set from the beginning. Many of you have probably come across “The Small Assassin” somewhere or other; it’s been anthologized countless times. Its ingeniousness wins out over its central implausibility because it sounds true: What is there in the world more selfish than a baby? I love the first line: “Just when the idea occurred to her that she was being murdered she could not tell.” Bold, mysterious, immediately gripping, just the kind of thing a Weird Tales reader would want.

That marvelous Bradbury prose is appropriate for younger readers while offering us adults plenty to appreciate and exclaim over; poetic and playful, with rich veins of darkness powering through, as in “Touched with Fire”:

“Some people are not only accident-prones, which means they want to punish themselves physically… but their subconscious puts them in dangerous situations… They’re potential victims. It is marked on their faces, hidden like—like tattoos… these people, these death-prones, touch all the wrong nerves in passing strangers; they brush the murder in all our breasts.”

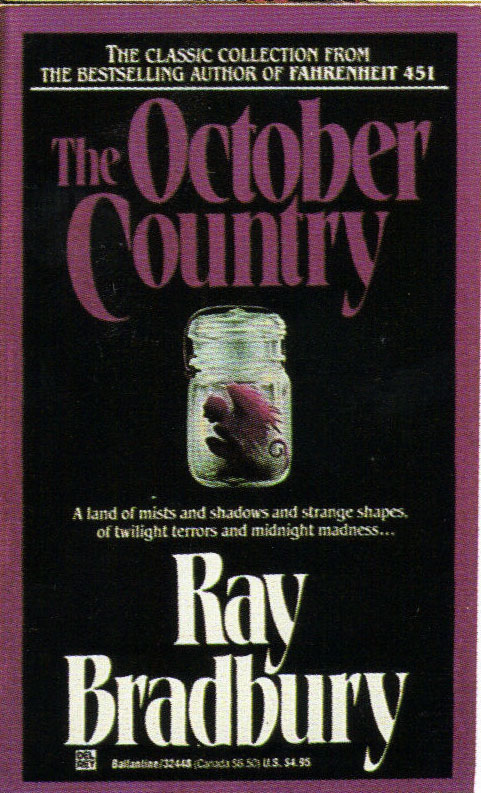

Some stories have such plain titles the words themselves take on a simple malevolence: “The Jar” (obviously the basis for the cover art at the top). “The Lake.” “The Emissary.” “Skeleton.” “The Crowd.” “The Wind.” As someone who finds blowing winds anxiety-inducing, I could really relate to that last one. There’s a vaguely Lovecraftian or Algernon Blackwood feel to it:

“That’s what the wind is. It’s a lot of people dead. The wind killed them, took their minds to give itself intelligence. It took all their voices and made them into one voice…”

Death appears—and well he should; is this not his country too?—in myriad forms: on an endless field of wheat, at 92 degrees Fahrenheit on the thermometer, in the very bones in our bodies, down in the earth itself. “The Emissary” starts off innocently autumnal with a sick boy in bed who lives vicariously through his roaming pet dog; it finishes not so innocently at all: “A rain of strange night earth fell seething on the bed.” Poetry!

Death appears—and well he should; is this not his country too?—in myriad forms: on an endless field of wheat, at 92 degrees Fahrenheit on the thermometer, in the very bones in our bodies, down in the earth itself. “The Emissary” starts off innocently autumnal with a sick boy in bed who lives vicariously through his roaming pet dog; it finishes not so innocently at all: “A rain of strange night earth fell seething on the bed.” Poetry!

Bradbury perennials like sideshows and carnivals feature in “The Dwarf” and “The Jar,” and his sense of boundless, mischievous joy buoys “The Watchful Poker Chip of H. Matisse” and “The Wonderful Death of Dudley Stone.” There is sadness too: Timothy, the young boy in “Homecoming,” yearns and yearns for a monstrous familial identity that will never be his, while “Uncle Einar” wishes he could be a normal father for his brood.

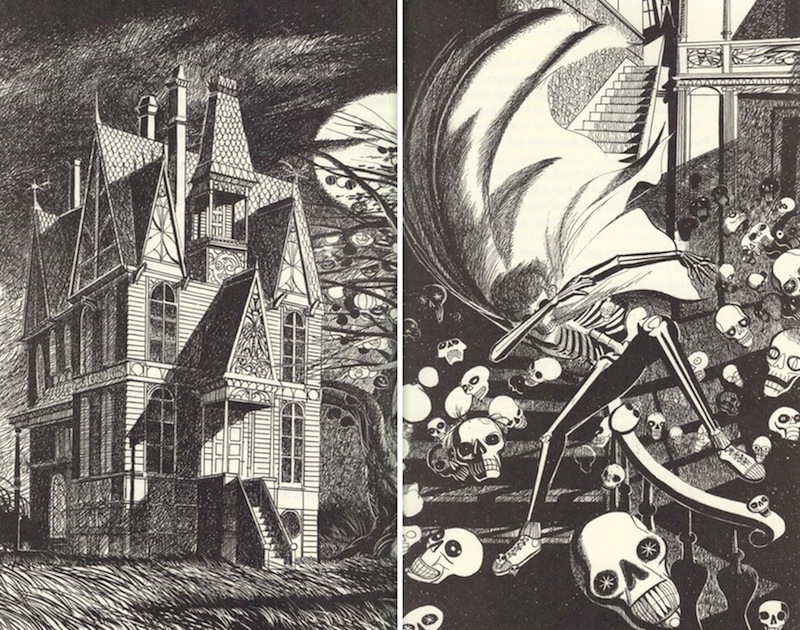

And I would be remiss if I did not note the stark and striking black-and-white artwork of Joseph Mugnaini that accompanies many of the stories, even in the many paperback editions published over the years.

It’s no surprise to state, finally, this collection is a horror classic for all ages for all the ages. Poised between the sweet and the scary, I see The October Country as a beginner’s book of horror; something to be given out like candy to eager children, to satisfy a sweet tooth, to prime burgeoning taste buds for a lifetime of fearsome entertainments. It is a must-read, a must-have, preferably in one of these musty old paperback editions, creased and worn from years of seasonal readings, of annual visits again and again to a “country where noons go quickly, dusks and twilights linger, and midnights stay. That country whose people are autumn people, thinking only autumn thoughts…”

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.

Love Bradbury. Please tell me October Game is in the book. That’s one of my favorites and right on point with the book theme.

@1: Alas, I feel that you must look elsewhere. “The October Game” may be found in Long After Midnight.

October is always my Bradbury re-reading season. (Except for Dandelion Wine, which tends to be re-read in June.)

Poetry of a very … umm, earthy variety, since “night earth” (aka “night soil”) is what is found in chamberpots and other receptacles for nocturnal bowel movements. But then, roses root better in fertilizer than they do in Parian marble.

I read my brother’s copy on a beach in spain when I was 9, so it is always means summer for me…

Great post!

This happens to be one of my all time favorites! I believe I enjoy The Emissary the most, followed by the story you mentioned first which I believe is actually titled The Next in Line, not The Last in Line.

As a young man, totally enthralled with Ray’s work, I purchased a copy of The October Country. It’s the Del Rey Edition featured in the image at the very top of the blog with the purple border and purple typeface for the title The October Country. Anyway, I delved into the book and found that my brand new copy was missing pages 119-150. A manufacturer’s error.

Although I was highly disappointed, especially because it interrupted my favorite story, The Emissary, it also made me salivate for more Bradbury.

I still own that “defective” copy of the book.

I love it.

As I left work near midnight last week, the gibbous moon hung in the sky, crisp leaves skittered along the pavement near my car, a scent of frost touched the night wind that pushed the leaves about. It all kept whispering “Miss you, Ray. Miss you, Ray”. Yes, Mr. Bradbury, we do.

@2 – I figured it must be missing. If any have not read October Game, do so. Subtle and chilling tale of a husband and wife who hate each other planning a Halloween party featuring their only child, a daughter.

Sounds like I need to track down this “October Game”!