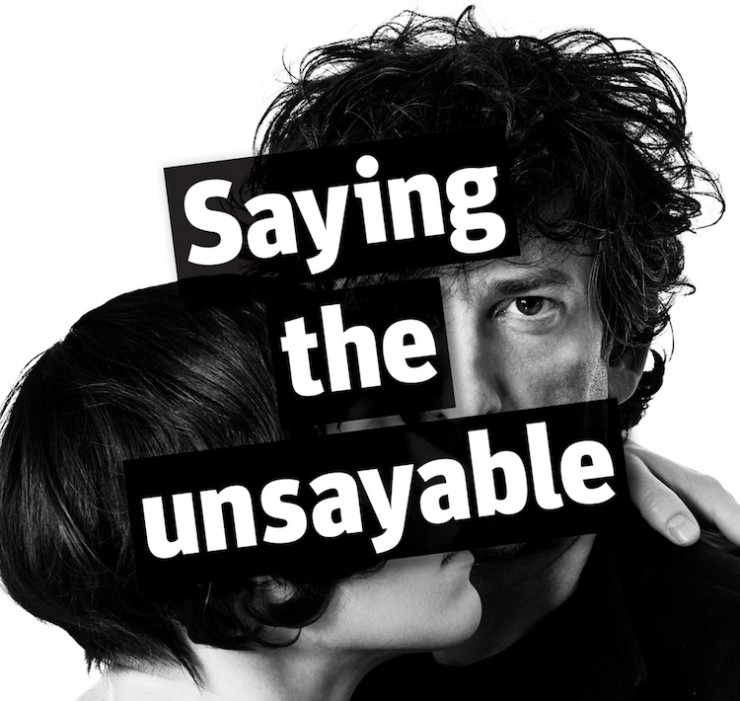

Neil Gaiman and Amanda Palmer recently guest-edited an edition of the New Statesmen. Working with the theme “Saying the Unsayable,” the pair used interviews, essays and comics from contributors including Stephen Fry and Laurie Penny to discuss censorship, internet outrage, and the unkillability of ideas. Part of this issue was dedicated to a long, fascinating conversation between Neil and acclaimed author Kazuo Ishiguro, whose latest novel, The Buried Giant, touched off a controversy when he seemed reluctant to categorize it as a fantasy. Click through for highlights from the interview!

Over the course of the talk, the two authors discuss genre in general, talking about how hardcore porn, musicals, and Westerns all need to conform to basic scripts. Ishiguro relates his initial culture shock when he first watched a long, Western-style swordfight:

When I first came to Britain at the age of five, one of the things that shocked me about western culture was the fight scenes in things like Zorro. I was already steeped in the samurai tradition – where all their skill and experience comes down to a single moment that separates winner from loser, life from death. The whole samurai tradition is about that: from pulp manga to art movies by Kurosawa. That was part of the magic and tension of a swordfight, as far as I was concerned. Then I saw people like Basil Rathbone as the Sheriff of Nottingham versus Errol Flynn as Robin Hood and they’d be having long, extended conversations while clicking their swords, and the hand that didn’t have the sword in it would be doing this kind of floppy thing in the air, and the idea seemed to be to edge your opponent over a precipice while engaging him in some sort of long, expository conversation about the plot.

The two authors compare their early careers, when an editor told Gaiman that Coraline was unpublishable, and Ishiguro’s biggest monster was the butler in The Remains of the Day. After a few decades of authors like David Mitchell, Michael Chabon, and J.K. Rowling, however, genre distinctions are becoming more and more flexible, allowing Ishiguro to explore sci-fi elements in Never Let Me Go, and risk baffling some readers with The Buried Giant. “Now I feel fairly free to use almost anything. People in the sci-fi community were very nice about Never Let Me Go. And by and large I’ve rather enjoyed my inadvertent trespassing into the fantasy genre, too, although I wasn’t even thinking about The Buried Giant as a fantasy – I just wanted to have ogres in there!”

For Gaiman, this genre collapse is obviously a longstanding passion, and he talks at length about his mad theories about the ways genre works, pulling examples from worlds as removed as Greek tragedy and hardcore porn. He also comes down solidly on the side of escapism:

I remember as a boy reading an essay by C.S. Lewis in which he writes about the way that people use the term “escapism” – the way literature is looked down on when it’s being used as escapism – and Lewis says that this is very strange, because actually there’s only one class of people who don’t like escape, and that’s jailers: people who want to keep you where you are. I’ve never had anything against escapist literature, because I figure that escape is a good thing: going to a different place, learning things, and coming back with tools you might not have known.

He goes on to call Shakespeare out on writing fan fiction, and to talk about the growing importance of sci-fi in China, while Ishiguro meditates on how the life of a culture contrasts with the life of an individual (“A society… can turn Nazi for a while… whereas an individual who happens to live through the Nazi era in Germany, that’s his whole life.”) and the two men come back, again and again, to the psychological needs met by storytelling itself. And of course, like all good Englishmen, they keep coming back to the two great pillars of English conversation: the class system and Doctor Who. (Ishiguro loved Gaiman’s first Who episode, and Gaiman wonders if the Doctor has become an immortally popular character like Sherlock Holmes.) It’s really one of the best discussions of art we’ve found in a long time, and we highly recommend reading the whole thing! You can find the interview over on the New Statesmen‘s site, along with some other articles from the special Gaiman ‘n’ Palmer issue.