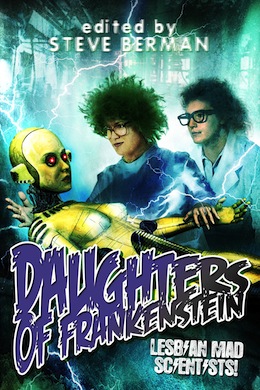

With the subheading “Lesbian Mad Scientists!” and a delightful cover that hearkens back to the pulp tradition—two women with frizzy hair bringing an android to life with lightning arcing all over the place—Daughters of Frankenstein is aiming for a very specific tone: fun. Lethe Press, under editor Steve Berman, regularly produces queer sf anthologies that I’ve appreciated, and this one in particular seemed likely to offer an entertaining late-summer read.

(I did, in fact, read it on the porch in the sun. Highly recommended activity.)

There are familiar names here, from Gemma Files and Claire Humphrey to Melissa Scott, as well as several that I haven’t seen before. Jess Nevins opens the collection with a scholarly overview of real and fictional women scientists, “From Alexander Pope to Splice: a Short History of the Female Mad Scientist,” originally published on io9 in 2011. From there, we have eighteen short stories, only two of which (Files and Stott) are reprints.

Overall, this is as entertaining a book as I’d hoped it would be—and in the exact vein the ethos of the cover art implies. While some stories have a touch of tragedy or horror, the majority are playing on the oddball intensity of the “mad scientist” to weave diverting, pleasant excursions into women getting weird with biology, history, chemistry, and technology. (Plus each other.) Nevins’ opening essay sets the tone well, too, drawing attention to the iconoclastic tendencies of the female mad scientist from the New Woman onward: someone who flaunts convention and forges individual paths, outside the acceptable frames of patriarchal social expectations.

There are a few stand-out stories here, but most are just nice, reasonably entertaining, and decent enough to read. Daughters of Frankenstein, then, is exactly what it wants to be: pulpy and playful light reading. If that’s something you’re looking for—Lesbian Mad Scientists!—you’ll like this and be satisfied with the offerings it contains. Some of the stories are a bit uneven in execution, and some run long or seem disorganized; the usual issues with up-and-coming newer voices, exploring their styles and the mechanics of telling a good tale. However, the general experience is good-weird.

As for some stories of note: Tracy Canfield’s Scooby Doo riff “Meddling Kids” is silly and popcorn-light, adding a tongue-in-cheek queer undertone to the mystery-solving high schoolers. The mad scientist and her assistant are ridiculous, as is the “reveal” at the end about the drive-in manager being the one behind the threats to himself. It isn’t credible in the real world and isn’t intended to be; it’s brief, amusing, and plays with tropes in a way that made me smile.

Another brief one is Claire Humphrey’s “Eldritch Brown Houses,” where two young women end up finding a bit of magic together—or, potentially, not. This story blends a sort of amateur scientific process (developing a camera procedure that can capture magic on film) with the supernatural, recalling the Salem witch trials and Lovecraft in the nrarative to bolster that connection between scientific approaches to nonscientific phenomena. But mostly, it’s just a gentle sweet piece, the story of a spark between two people starting up.

“The Eggshell Curtain” by Romie Stott, one of the only reprints, takes place during the Bolshevik revolution. The protagonist herself isn’t a mad scientist, interestingly enough. She’s more the victim of mad science: her father imprisons her in a Faberge egg, having miniaturized her and frozen her in time. She doesn’t age, so she eventually becomes the voice of historical continuity for the future. It’s a bit of a meandering piece, but Stott’s representation of her protagonist’s simple but concrete worldview is engaging. The romance with Nyusha feels adolescent and appropriately underdeveloped, as well, though her father’s reaction to it also seems a bit extreme.

Traci Castleberry’s “Poor Girl” mixes up several tropes—a person assigned female at birth living as a man, including being a pirate and learning Chinese traditional magic (our protagonist is half-Chinese herself), who is at first a cold unfeeling scientist but then falls in love after being punished for hubris and cruelty by that very magic. It’s competently written, though, and does the “pseudo-Victorian mad science story” thing well enough to be engaging.

One of my favorites was Melissa Scott’s story, though, which came next: “Bank Job Blues,” about some heist-running lesbians, set when it was easier to say Sapphists. I liked the action of the piece, the atmospheric tension between the bank job crew, and the sense of impossibility in living in the strictures set out by the culture on women who love women. I also liked how they get away with it, so far as we know, and decide to keep on trying together. It’s very Bonnie-and-Clyde, but with a gang of butch dykes and femmes. Good stuff.

Gemma Files’s reprint, “Imaginary Beauties: A Lurid Melodrama,” is also a solid story, though much darker and more—well, lurid—than the rest. A much more accurately contemporary feel, too: damaged weird girls making bad drugs, going out together in a blaze of (stupid) not-glory. The exploration of social versus technical genius between the two women here is also interesting, particularly because of what a genuinely bad person Rice—our protagonist—is.

Then there’s Amy Griswold’s “Hypatia and Her Sisters,” which is a bit of Victorian mad-science with a down-on-her-luck governess and a genius inventor who have a plot to get rich, subvert traditional girls’ education in the patriarchal moral system, and run away together. I kind of loved this one, for its straightforward sensibilities and how entertaining it was to read. It’s the sort of thing I’d hoped for from this book, and was glad to find within it. The last story, though, is a tragic one that provides an interesting closing note: Megan Arkenberg’s “Love in the Time of Markov Processes”—infinite universes, but none in which the protagonist’s beloved loves her back. I did appreciate it, and the thoughtful tone it gives the book’s close.

All together, a pleasant summer read delivering exactly what it says on the tin. If this is up your alley, you’ll probably quite like it: weird, fun, playful, and full of lesbians doing mad science and breaking out of social conventions. Berman has done a good job at collecting stories that fit well together, and even the ones I didn’t care for or found a bit tedious weren’t terrible; it’s your usual romp of an anthology, with a subject that devotes itself to high-energy entertainment more often than not. Worth picking up.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.