Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

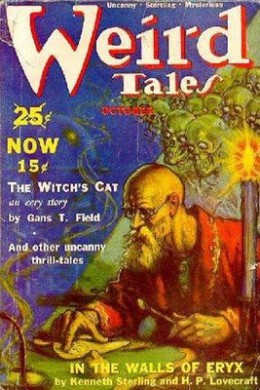

Today we’re looking at “In the Walls of Eryx,” a collaboration between Lovecraft and Kenneth J. Sterling written in January 1936, and first published (posthumously for Lovecraft) in the October 1939 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead!

“Staring back at these grotesque and unexpected intruders, and wondering uneasily why they did not attack me at once, I lost for the time being the will power and nervous energy to continue my search for a way out. Instead I leaned limply against the invisible wall of the passage where I stood, letting my wonder merge gradually into a chain of the wildest speculations. An hundred mysteries which had previously baffled me seemed all at once to take on a new and sinister significance, and I trembled with an acute fear unlike anything I had experienced before.”

Summary: Prospector Kenton Stanfield has arrived on Venus to search for “crystals.” These are super-valuable, given one egg-sized crystal can power a city for a year. Too bad the native “man-lizards” guard the main deposits, leaving humans to scrounge for scattered specimens in jungle riverbeds. The man-lizards worship the crystals, but Stanfield’s not convinced they’re sapient, despite their cities and weapons and seeming use of chest tentacles to communicate with each other. He’s confident that one good Earth army could wipe the “beggars” out, and good riddance.

Armed with crystal detector, food tablets, respirator mask and flame pistol, Stanfield sets off through the thick Venusian jungle. He encounters dart-shooting man-lizards (the flame pistol makes short work of them), hallucination-producing plants, and various pesky wrigglers. His quest leads him to the plateau called Eryx, at the muddy center of which he detects a big crystal. It’s raised above the omnipresent slime by a mound that turns out to be the corpse of another prospector. Stanfield can’t immediately reach either crystal or corpse, for he runs head-on into an invisible barrier.

After picking himself out of the mud, he confidently investigates, learning that the barrier is the curving wall of a vast enclosure, nonreflective and nonrefractive, glassy smooth, about twenty feet high. He edges along it toward the corpse and finds an opening. The dead man is Dwight, a veteran prospector. Stanfield relieves him of a crystal bigger than any he’s ever seen and proceeds to explore the enclosure, which turns out to be divided into many halls and rooms. Confident that he’ll be able to find his way back out, he spirals inward to the center of the place: a circular chamber ten feet wide, floored with mud. What forgotten race of highly evolved beings made the structure? Surely not the man-lizards. Perhaps it’s a relic of ancient aliens who preceded them. But what can be its purpose?

He gropes his way confidently back toward Dwight, whom Venusian scavengers have begun to swarm. He ends up in a parallel hall, unable to reach the door through which he entered the enclosure. He must have taken a wrong turn on his return. He will soon make many wrong turns, as he flounders through the invisible but impenetrable maze.

Days pass. He tries cutting the walls, but his knife leaves no mark, nor does his flame pistol melt them. He tries digging under; the walls extend through the mud to rock-hard clay. His food and water and respirator recharging tablets are running out. Then the man-lizards arrive, a throng of them that crowd up to the enclosure to watch his struggles, their chest tentacles waggling mockingly. They cluster thickest near Dwight, now a picked skeleton—if Stanfield ever reaches the exit, he’ll have to shoot his way out.

Stanfield keeps trying to escape, recording his efforts on a rot-proof scroll and wondering if the man-lizards aren’t pretty damn sapient after all, smart enough to have devised the enclosure as a human trap. They don’t advance toward him—too bad, as that would have given him a clue to the route out. Instead they watch and imitate his raging gestures.

Food and air running out, water gone, he grows too weak to rage. As he lies waiting for rescue or death, his mind wanders to a more conciliatory place. Humans should leave the crystals to Venus, for they may have violated some obscure cosmic law in trying to seize them. And after all, who knows which species stands higher in the scale of entity, human or man-lizard? Who knows which comes closer to a space-wide organic norm?

Just before Stanfield dies, he records seeing a light in the sky. It’s a rescue party from Terra Nova. Their plane strikes the invisible structure and is downed. They drive off the man-lizards, find the two bodies and the big crystal, call in a repair plane. After discovering and reading Stanfield’s scroll, they come to a different conclusion about the man-lizards. They mean to adopt his earlier, saner proposal about bringing in a human army to annihilate them. They will also dynamite the invisible labyrinth, since it poses a menace to human travel.

Oh, and know what the ironic thing is? Like Dwight before him, Stanfield gave up trying to escape from the maze when he was actually only a few steps from the exit.

What’s Cyclopean: N-force. Flame pistols. Long, ropy pectoral tentacles. All in a day’s pulp.

The Degenerate Dutch: The restless natives must be either stupid, or evil. And if evil, they must be in league with terrible forces beyond our ken…

Mythos Making: De nada, unless the restless natives really are in league with terrible forces beyond our ken, with names that begin with C.

Libronomicon: Observe, if you will, the tough, thin metal of this revolving decay-proof record scroll.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Surely those restless natives are merely stupid. Any other suggestion must indicate mental decay on the part of the narrator.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

There are Lovecraft stories that carry an instant dark power—that for all their flaws, are clearly classics that have survived three quarters of a century with good reason. While his solo work is better known, many of his collaborations still have that power, with fearful imagery that can lurk in a reader’s head for years.

Then there’s “In the Walls of Eryx.”

I don’t want to diss too much on this story, because in high school I wrote some of the pulpiest pulp that ever pulped. (It was cyberpunk pulp, with tropes only marginally less hoary than Venusian lizard men.) And it’s kind of sweet that Lovecraft took Kenneth Sterling’s high school pulp and filled it in with tentacles and existential horror. Boy, am I glad no potentially-famous-in-the-22nd-century author did me that kind of favor 25 years ago.

And yet, in spite of the fact that in a year I’m likely to remember little beyond “invisible maze on Venus,” this story is doing something kind of cool. It starts out as a pure and perfect sci-fi pulp: the narrator full of macho confidence in his place at the top of the food chain, the macguffin crystals, the hostile atmosphere that demands only a breath mask and leather skivvies for survival. Flame pistols, food pills, and lizard men on Old Venus. The narrator is too stupid to live, but he surely will—provided he’s in the story this starts out looking like.

And then, just when all seems lost… it turns out that he’s in a Lovecraft story and everything is much, much worse than it appears. The “lizard-men” have frog-slick skin and tentacles, and suction cup feet adapted to Venus’s muddy landscape. Oh, and they’re just a front for “dark, potent, and widespread forces,” “the prelude of greater horrors to come.”

Lovecraft knows, as we’ve seen, that proud anglo men aren’t kept atop the food chain by divine right. (He disapproves of this.) Sooner or later they and their civilized notions will fall to the inevitable destruction that awaits any civilization, doomed by the “arcana of the cosmos.” Here, he even implies how it happens: a little too much hubris, and the attempt to bring terrible destructive forces to bear against something that has quiet access to forces yet more terrible, yet more destructive.

And near the end of the story, Stanfield feels some sympathetic kinship with the lizard men. “In the scale of cosmic entity who can say which species stands higher, or more nearly approaches a space-wide organic norm—theirs or mine?” It’s a good question—and one wonders how much the asking of it was meant to be horror. Kinship with the alien plays a role in most of Lovecraft’s later stories. Even if “Eryx” stands out in no other way, it deserves mention as a marker of progress in that dance of revulsion and attraction.

Anne’s Commentary

Kenneth J. Sterling was a Providence high school student who befriended Lovecraft in 1934. The next year he sent Lovecraft the draft of a story about an invisible maze, which Lovecraft appears to have revised heavily, roughly doubling the word count. Certainly his mark is all over the fairly straightforward science fiction of near-Earth exploration, and exploitation. In its pragmatic tone and tech/pseudotech descriptions, it resembles the first part of At the Mountains of Madness. In its attitude toward the Venusians, or “man-lizards,” it displays the extremes of Lovecraft’s intellectual evolution. Though “Kenton J. Stanfield” appears to play on the co-author’s name, Stanfield might be more of a stand-in for Lovecraft than for his young friend.

Stanfield starts out a xenophobe among xenophobes. The Venusians are “damnable,” “scaly beggars,” “skulking,” “detestable,” “repulsive,” “sly,” mistakable for “men” only because of their upright posture. The fact that the Venusians build elaborate cities and towers doesn’t sway him—those things are analogous with anthills and beaver dams. Their weapons are primitive, swords and darts. Other humans may think the complex movements of their pectoral tentacles represent speech, but Stanfield’s not buying it. He does buy that the man-lizards worship the coveted crystals of Venus, but without thinking through what the act of worship implies about their intelligence. Nope. Just a bunch of slimy pests. He’s all for wiping them out so real men can harvest as much crystal as they want from the vast motherlodes.

Prior to Eryx, Stanfield has seen Venusians only in glimpses through the jungle tangles. Observing them and their interactions through the invisible walls of his cage, he begins to doubt his former rejection of the tentacle-language theory. Okay, so they can talk. Okay, so maybe they were the ones who built the invisible labyrinth, not ancient aliens of a brainier ilk. Built it as a human-snare! So they’re smart, but they’re still a bunch of mocking bastards, full of “hideous mirth” over his discomfiture.

It doesn’t occur to him that when the Venusians imitate his fist-shakes, they may be trying to communicate in his own “lingo.” It doesn’t occur to him that they may cluster around the exit to help show where it is. That they don’t enter themselves because they might be afraid of the place and its uncanny capacity to trap intruders.

Those things never do occur to Stanfield, but as he weakens into acceptance of impending death, he does experience an epiphany. His would-be rescuer will record his change of heart as madness. I think it’s breakthrough sanity, a trauma-induced dropping of scales from his eyes. It comes suddenly to be sure, as the length of the story demands, but I think Lovecraft means us to read Stanfield’s more “kindly” apprehension of the Venusians as sincere. What’s more, and more late-Lovecraftian, Stanfield begins at the end to think in cosmic terms. Laws are buried in “the arcana of the cosmos.” “Dark, potent, and widespread forces” may spur on the Venusians in their reverence for the crystals. And there are “scale(s) of cosmic entity,” perhaps “space-wide organic norm(s),” and who knows which is the higher species, Terran or Venusian?

Stanfield comes to the same realization as Dyer did a few years earlier in Mountains of Madness. Whatever else they may have been, the star-headed Elder Things were men. Thinking and feeling, making and destroying, rising and falling, flawed yet worthy, because there, in the scale of intelligent creatures. Men, in our parlance, self-centered but hence accepting, including.

As for the invisible maze, I’m still wondering who made it. The Venusians of the story may be great builders, but the maze comes across as supremely, sleekly high-tech, which doesn’t jibe with the swords and darts thing. I’m inclined to think that Stanfield was right the first time—another race made the maze. Aliens to Venus or earlier indigenous sapients? Maybe a superior man-lizard civilization, the man-lizards now being in decline? That’s a Lovecrafty notion, which we’ve seen him apply to the Elder Things of Antarctica and the inhabitants of subterranean K’nyan.

Or, or, maybe it’s the crystal itself that creates the maze! Maybe the complex and possibly shifting structure is the material expression of its energy and “condensed” out of it. Now that would be coolness.

The (oddly unnamed) crystals fit into the trope of A Thing of Ultimate Civilization-Changing Power. Like Star Trek‘s dilithium crystals, heart of the warp engine. Like Dune‘s spice, necessary to the navigation of space. Like John Galt’s generator, producing endless cheap energy from static electricity. Very like Avatar‘s unobtanium, though the Na’vi are a lot prettier than the man-lizards. That Stanfield can conceive of Earth leaving the crystals to the Venusians proves he’s getting giddy. Humans never leave treasure in the ground, especially when they get together in Companies and Empires and whatnot.

Next week we cover one of Lovecraft’s more obscure pieces: “The Transition of Juan Romero.” After that, the long wait ends as we finally give into pressure and celebrate Halloween “At the Mountains of Madness!”

Ruthanna Emrys’s non-Hugo-nominated neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. The second in the Redemption’s Heir series, Fathomless, will be published on October 27, 2015. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

“In the Walls of Eryx” is minor and rather repetitive but I retain a fondness for this off-beat collaboration.

Weird Tales: October 1939, with Manly Wade Wellman’s “The Witch’s Cat” and a reprint of Robert E. Howard’s “Worms of the Earth”. An excerpt from Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Hashish-Eater” accompanies a Virgil Finlay illustration.

Who Wrote What?: Lovecraft is said to have extended the story extensively: I suspect that the two author’s contributions were on the whole about equal.

Kenneth Sterling: was a friend of Lovecraft’s who wrote this story as a teenager. He had previously sold three other stories (all to Wonder Stories) and later wrote a couple of essays about Lovecraft, both of which may be found in Peter Cannon’s Lovecraft Remembered. He stopped writing fiction after this, apparently due to his decision to train as a doctor.

Lovecraftian Science: proves, as ever, indispensable.

I briefly stifle noises of delight to enquire: how exactly will At the Mountains of Madness be split up? Three parts, as in the original serial?

Our narrator certainly starts off as a right asshole. I really do wonder just how sympathetic we’re meant to be to his initial POV. His utter refusal to see anything intelligent about the Venusians is almost hard to accept. The only thing I can think of that comes close is the bad guys in H. Beam Piper’s Little Fuzzy, who are rather willfully blind to obvious intelligence, but then they’re the bad guys (who reform by the next book). Does Stanfield really reform here or is this more an attitude of “They’ve beaten me and I can’t be beaten by mere primitives, ergo they are much more superior than I thought”?

Sterling was apparently inspired by Edmond Hamilton’s very first published story, “The Monster-God of Mamurth” (Weird Tales, August 1926), which also features an invisible building. The narrator there fares slightly better, since the building has a simpler layout, but he only lives long enough to tell his tale. It’s fairly Lovecraftian, actually.

The names of the various Venusian flora and fauna are apparently digs at a few people in the SF world. Akmans and efjeh-weed seem to be shots at Forrest J. Ackerman, with whom HPL was feuding because Forrie didn’t like some CAS story. Farnoth flies get their name from Farnsworth Wright, who edited Weird Tales and ugrats derive from Hugo the Rat, which is what Lovecraft called Gernsback. I also wonder if the “mud-dwelling sificlighs” are derived from “sci-fi cliques” or something similar.

Stanfield never thinks that the Venusians might be trying to communicate in his lingo, or might be trying to show him the way out of a maze that is scary to them too, because I suspect it never occurred to Sterling or Lovecraft. Just because the aliens are possibly more intelligent and civilized than bigoted white men assume, doesn’t mean they are friendly.

I haven’t read the story–might try to tonight–but I wonder to what extent it is a comment on the real history and/or fictionalized stories of Great White Hunters going to Deepest Africa and assuming they know everything and the natives are mere savages.

@2: “The Monster-God of Mamurth” was, I remember, one of the few Edmond Hamilton stories Lovecraft liked.

The Ackerman thing came about because Forry said that Smith’s “Dweller in Martian Depths” wasn’t sfnal enough for Wonder Stories in the The Fantasy Fan’s “Boiling Point” column: Smith, Lovecraft and R. H. Barlow disagreed. I don’t think Smith had any hard feelings: by the end of his life, Ackerman was working as his agent. Ackerman had another Lovecraftian connection in that, as a schoolboy, he sold Fritz Leiber tearsheets of “The Silver Key” and “The Whisperer in Darkness”.

@2: I had no idea about the sources for the names! As with most things of that sort, I just kind of gleeped right over them.

And this story was always an odd duck for me, mostly by virtue of its explicit SFness and interplanetary setting.

I thought that he could have gotten out if he had dropped the crystal, but at the end the other people seem to be able to take it out of the labyrinth.

Lovecraft doing pulp-era SF: Fantastic Venus! Lizard-men! Alien crystals!And the added pleasure that comes from the genesis of the tale. An adolescent fan’s dream come true, learning that the greatest living American horror writer, the peer of Poe and Bierce, is your neighbor. And, after you work-up the nerve to knock on his door, he invites into his house and engages you in a lengthy chat on the horror field! And then he agrees to co-write a story with you!

Sigh. Why other Lovecraft stories couldn’t be more like this in their outlook? It fits his view of indifferent universe much better than “THEM are everywhere, coming to destroy the precious white civilization” of earlier stories. I don’t mind pulp – it gives the story a cozy “retro” feel and make it seem somewhat refreshing, a break from more traditionally Lovecraftian stuff. It is definitely one of his most unusual stories.

Like birgit, I remember when I read this story that I had the impression that the maze was constructed around the crystal. But then, that theory is blown up by the ending, when the rescue team retrieves the crystal. I suppose it seemed significant that both Kenton and Dwight died just a few feet from the entrance. Mystifying as it is, I do enjoy the pulpy elements of this story, wonderfully overblown as they are.

My assumption was that the maze shifts so that the body of the previous victim is always close to the entrance, tempting the next person to explore.

Cool insight into the names, thank you!

SchuylerH @@@@@ 1: Your suggestion is a tempting one, but Google fails me. I don’t suppose you (or any of our other intrepid commenters) know the precise location of the divisions for the serialization?

@11: I have been unable to track it down exactly: the Astounding serial was cut for length by Tremaine and otherwise altered. It could be done in three parts as chapters 1-4, 5-8 and 9-12 (there’s certainly enough material there). Alternately, Lovecraft suggested to Derleth that a single serial division could be placed in the middle (due to the uneven chapter lengths, this might be nearer to 1-5 and 6-12).

Not read this before but i enjoyed the pulpyness of it, not something i expected of HPL.

At the mountains of madness you say? Ooh boy! I was starting to think you’d forgotten about it. Good excuse to read it again amongst the pile of other stuff i want to get through.

Not explicitly Lovecraftian but still of interest: Adrian Tchaikovsky’s “Children of Dagon”.

With the soggy-jungle Venus of “In the Walls of Eryx,” Lovecraft doesn’t come as close to reality, as we know it today, as he did with Pluto in “The Whisperer in Darkness.” But neither did many others guess it would be an uninhabitable roasting-hot, sulfuric-acid-ridden hellhole beneath its clouds.

Nevertheless, I do see a major technical problem with making the maze truly invisible. The base of the invisible walls should manifest as a complex of apparent vertical-walled trenches in the mud, which ought to be entirely obvious. One can explain this away by speculating that the structure is so technically sophisticated that the appearance of a mud surface is somehow mirrored across the gap between the actual mud surfaces. Still, it would be quite complicated to make this effect so perfect as to efface all visual hints of the true bottom of the walls.

@15: I actually looked it up and the idea of a wet Venus remained scientifically plausible until sometime in the 50s. I’m often surprised by how much knowledge that I take for granted wasn’t really known until not long before I was born or even my early childhood.

Real-life invisibility technology, currently in its infancy, appears to involve light-bending rather than making objects perfectly clear. So not seeing the trenches actually makes more sense from a modern perspective.

On the other hand, yeah, wet Venus where you can see Earth through the atmosphere has not aged well. Not his fault–just a hazard of the profession. It’s a little startling to me sometimes how some of Lovecraft’s SFnal speculation has lasted better than “hard SF” writers who were trying to make plausible extrapolations. “Freak out over the universe’s sheer awesome magnitude and variability” seems to be a good strategy on this count.

Belated fridge logic: would it have been possible to escape using the wall follower method or the pledge algorithm?

Yes–assuming the maze doesn’t cheat, and that the time to follow the walls isn’t longer than the time in which one can die from dehydration.

@18 I had the same thought as I was reading. “Just keep turning left, you’ll get there eventually.”

Although I did wonder once or twice if the maze might be changing behind his back.

I’m coming way late to the party (I found Ruthanna and Anne’s notes while doing my own – still ongoing – reread), but I have an idea no one else has brought up.

Others have noticed that the men-lizards might be gesturing and clustering by the entrance in an effort to communicate with and help Stanfield out. But what if they’re doing even more than that? Visualize it: we have a creature of one type trying to find its way out of maze while scores of creatures of a second type hover around the maze. The watchers “switch off” as if they’re on a clock and occasionally get very excited at Stanfield’s movements. They don’t go into the maze, but they do seem to hope he’ll get out. Why? Well, I think they’re alien scientists and he’s the rat in their maze.They’re testing human intelligence and using the crystals as motivational food pellets.

And here’s another thing. I think they might have been getting ready to rescue him (because they were lighting their torches) before the approach of more humans scared them off. They might have tried to rescue Dwight too, and he could have mistaken their intentions and killed himself before they could (as he thought) kill him.

If I’m right, then they understand the crystals far, far better than humans and probably used crystal power to make the maze – and shift its walls, perhaps. I hope that power will be enough to save them once the humans come back in force and try to wipe them out.

Yet further thread re-animation as I’ve only recently discovered these re-reads: I always thought that whether the crystal was visible/exposed somehow triggered changes to the maze layout – while it was sitting on the previously corpse the maze was open, and when the protagonist packs it away the maze inserts additional invisible barriers.

As the protagonist faces impending doom, they take it out again, unbeknownst to them also reopening the way they are too weak to follow…