There are many ways to structure a magic system in a fantasy story, and even though expressing magic through language is one of the most obvious methods for a story to utilize (“abracadabra!” and all that), it is also somewhat rare. Language is precise, complex, and in a constant state of change, making it daunting for an author to create, and even more daunting for a reader to memorize.

There are some interesting shortcuts that fantasy stories have utilized over the years, however, some of which are utterly fearless in tackling the challenge inherent in crafting a complex magical language.

For Beginners

Just use Latin: Supernatural, Buffy, et al.

The Roman Catholic Church pronounced Latin as the official language of the church back in 313 C.E. and still utilizes it for sermons and rituals. In the first millennium, the Church used Latin to “dispel” demons from this Earthly plane during exorcisms, the thinking being that God’s word and sentiment was most clearly and directly expressed in Latin, and what demon could withstand such a direct proclamation?

As such, Latin has become identified as containing a mystical, ancient, and otherworldly quality. TV shows and movies with an urban fantasy bent to them, like Supernatural or Buffy the Vampire Slayer, tend to fall back on this shorthand in order to avoid having to create and explain an entire mystical language to their viewers. Latin has become the go-to, off-the-shelf basic package for magical language in a fantasy story.

Memorize these terms: Harry Potter by J.K. Rowling

Most spells in the Harry Potter series require a vaguely Latin-esque verbal incantation, although author J.K. Rowling adds a bit of complexity in that these verbalizations need to be demonstrably precise and usually must be accompanied by a specific wand movement. The language magic in the Harry Potter series is one of the few areas of Rowling’s world that remains simplistic: being essentially a dictionary of terms and phonetics to memorize, which is in marked contrast to other worldbuilding aspects to the Harry Potter world. (The Black family tree has more complexity than the world’s entire magic system does.) This makes the language magic easy for young readers to internalize, turning the magic into a series of slogans (“Accio [peanut butter sandwich]!” “Expecto Patronum!” “Expelliarmus!”) instead of a list of terms.

There is an aspect to Rowling’s language magic that interesting and that we may see explored further in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: non-verbal magic used by adults. There are many instances in the book series where older characters are able to create complex, and massively powerful, spells without needing to verbalize them. Does this suggest that language magic in the Harry Potter universe is simply a bridge, a tool of learning, to more complex, non-verbal magic? Or does language magic simply become a reflex over time?

For Intermediates

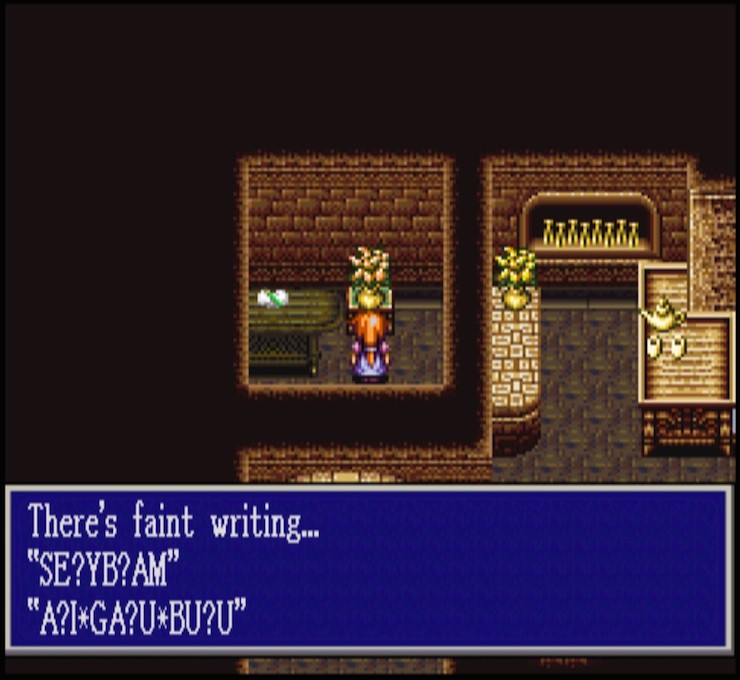

Mix and match until something works: Treasure of the Rudras

Treasure of the Rudras is a 16-bit RPG game that harkens back to the wistful days of Final Fantasy, Chrono Trigger, and Breath of Fire. Although where the aforementioned games would give you predetermined spells to select and use, Rudras differed by creating a basic system that allowed the player to construct their own spells by grouping specific syllables of a language. Crafting a basic element name would summon the weakest version of that spells, but experimenting with adding specific suffixes and prefixes would enhance the strength of those spells, and unlock other added effects. This system was beautifully simply in execution, allowing the developers to skip creating an entire magical language while still giving players the impression that they were active participants in learning and using a magical language. Fittingly, beating the game requires the player to use what they’ve learned of this syllabic magic language system to create a functional and unique spell.

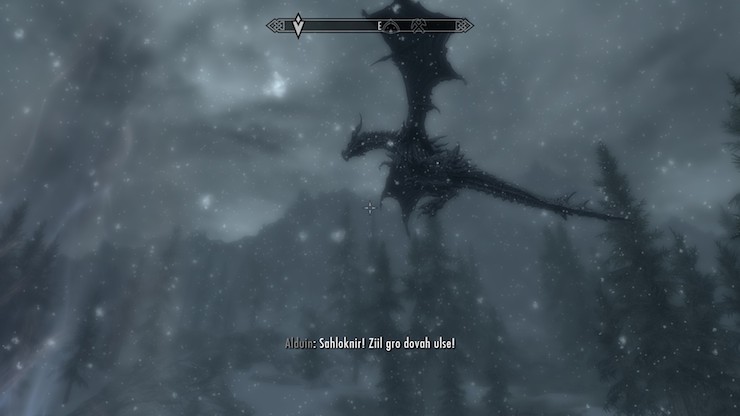

Let’s have a chat: The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim

With the introduction of dragons into the Elder Scrolls franchise came the introduction of the dragon’s language. Functionally, this is the same syllabic system as seen in The Treasure of Rudras, although without the interactivity. Your character is able the use the dragon’s language as form of intensely powerful magic (known as a Thu’um, or Shout), and you do learn specific words and calligraphic symbols for this language, but this only allows the player to translate some of the game’s narration as opposed to crafting new spells.

Still, Skyrim does have one unique use of magical language: The realization that a dragon roasting you with its fire breath is probably just it asking if you’d like a cup of tea.

Negotiation: The Inheritance Cycle by Christopher Paolini

What makes the Ancient Language (also the language of the elves) in the Inheritance Cycle unique is that it is a language that affects the universe, but does not allow the universe to read the intent of the caster. So if a character wants to heal a broken shoulder, they can’t simply incant “Heal!” in the Ancient Language. Rather, the caster must be very specific in what it wants the universe to do–move this muscle back into place first, then fuse these two bones, then move that fused bone, etc.–in order to use magic in any useful sense. Where simpler language magics are about finding the correct key for an existing lock, language magics of intermediate complexity add interaction and negotiation with a third party into the mix. In essence, it’s not enough to know the language and its terms, you have to be able to converse in that language, as well.

For Advanced Users

Fluidity and interpretation: The Spellwright Trilogy by Blake Charlton

Magic in Blake Charlton’s Spellwright trilogy, which concludes with Spellbreaker on August 23rd, is a complete character-based magical language consisting of runes that can be formed into paragraphs and larger narratives by the reader and the characters within the fantasy world. Where the Spellwright trilogy focuses its story is in the interpretation and fluidity of that language, asking how a magical language would progress if interpreted and expressed by an individual who would be considered dyslexic in that world. Every Author (as the wizards in this series are called) must be a sufficiently advanced linguist capable of duplicating the runes perfectly in order to use the magic. However, language, while precise in use, is not static over time. Terms change rapidly (ask someone living in the 1980s to “google” something for you, for example) and pronunciations change over regions. (NYC residents can tell you’re from out of town by the way you pronounce “Houston St.”, for example.) The Spellwright series explores the rigidity of language and the necessity of fluidity and error with incredible detail.

The world emerges from the language: The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

The universe in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings was “sung” into existence, and one of the reasons Tolkien is such an undisputed master of the fantasy genre is that he did the work of creating the language that created his universe! Not only that, Tolkien saw how a singular language would be affected by region, nationality, and time, and derived the languages of Middle-earth as branches from that ur-language. Magic that we see used in The Lord of the Rings is entirely-based on that ur-language, and the characters that use it most effectively–Sauron, Saruman, Gandalf, the elves–are the ones with the most direct connection to that originating language.

It is a testament to the power of the magical languages in The Lord of the Rings that they can reach beyond their fictional basis to affect the real world. Conversations can be conducted in Elvish, a child’s name can be (and has been) constructed from Tolkien’s language (“Gorngraw” = impetuous bear!), and the weight of its utility in turn makes the fictional Middle-earth feel incredibly real.