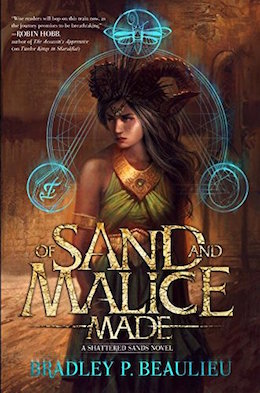

Çeda, the heroine of the novel Twelve Kings in Sharakhai, is the youngest pit fighter in the history of the great desert city of Sharakhai. In Of Sand and Malice Made—Bradley Beaulieu‘s prequel novella, available September 6th from DAW—she has already made her name in the arena as the fearsome, undefeated White Wolf; none but her closest friends and allies know her true identity.

But this all changes when she crosses the path of Rümayesh, an ehrekh, a sadistic creature forged long ago by the god of chaos. The ehrekh are usually desert dwellers, but this one lurks in the dark corners of Sharakhai, toying with and preying on humans. As Rümayesh works to unmask the White Wolf and claim Çeda for her own, Çeda’s struggle becomes a battle for her very soul.

Preview Of Sand and Malice Made below, and be sure to also check out this excerpt from Twelve Kinds in Sharakai, book one in the Song of Shattered Sands series!

Born of a Trickster God

Late that evening as the sun was setting, Emre led Çeda to Sharakhai’s sandy western harbor. Walking along the misshapen arc of the quay, they eventually came to a tumbledown pier, where an old sloop was moored.

“This is where we’re to meet him,” Emre said.

Çeda pointed at the ship. “Here? It looks like the Silver Spears beat it and left it for dead.”

“It’s just for appearances,” Emre replied, though his voice was far from confident. “He doesn’t want to attract undue attention. You of all people should understand that.”

“Well, it seems to attract termites well enough,” she said under her breath. “Will it even sail?”

“Let’s hope so,” he said, and proceeded down the pier, stopping just short of stepping across the narrow gap between ship and pier and onto the deck of the sandship. Çeda followed, watching as a towering Kundhunese deckhand moved about the ship with a lantern, golden light reflecting eerily off his black skin. Three other crewmen climbed along the rigging, preparing the sails and tidying a ship that looked as patchwork as patchwork could be.

“We’re here for Adzin,” Emre said.

The hulking Kundhuni lifted his lantern and shone it, first on Emre, then Çeda. He seemed ill-pleased, but in the end he grunted, swung the lantern toward the open hatch near the gangway, and walked away. As the lantern cast ghostly patterns against the masts and rigging, Emre motioned for Çeda to go ahead of him. After stepping onto the ship and crossing the deck, she took an angled ladder down to a passageway that made her shiver just to look at it.

Its walls and ceiling were lined with hooks, and from these, strings were looped like the weave of some madman. Tied to the strings were an assortment of ornaments and oddments that were dark-stained, feculent, misused, as though each had been plucked from the grip of a freshly dead hand: a bent awl, its aged wooden handle cracked; a misshapen pair of wrought iron scissors; a tarnished silver ring with a setting filled with what appeared to be children’s teeth; a string of—dear gods, were those fingernails?—hung loosely around the neck of a wooden doll with the face of a little boy painted on it. Çeda hadn’t slept since her talk with Emre. She’d practically staggered onto the docks and along the pier, but now her blood was flowing, returning to her some small amount of steadiness as she did her best to touch not one bloody thing on this strange ship.

“Adzin?” Emre called from behind her.

“Come, come,” an effeminate voice answered from beyond the open doorway at the end of the hall.

They reached the doorway and found a room blessedly free of mad adornments. Within it stood a mouse of a man. He wore a black kaftan a bit too large for his frame. He had a pinched expression on his face, and his hands were clasped before him. Oddly, though, his left hand was massaging the meat of the opposite thumb, as if it had cramped. He regarded Emre with a flat expression. “You’re Osman’s man?”

Emre nodded, and Adzin turned to Çeda. “Which would make you the one.”

Çeda hadn’t been nervous about carrying so much money with her through the streets—she’d been too exhausted to worry over it—but she was nervous now. Adzin seemed the sort of man that would hardly think twice about driving the tip of a bent, broken awl into someone’s kidney for a purse the size of the one she and Emre had brought for payment.

“I’m the one,” she replied carefully.

“You have my coins?”

“We’ve come to find a man,” Emre said.

Adzin moved behind a low table, where he reached up and pulled the string of a brass bell hanging from the thick wooden beam above him. The bell rang, the sound shrill in the cramped space of the cabin. Soon after, Çeda heard men dropping to the sand, felt the gentle tilt of the ship as it was towed away from the pier toward the harbor’s center.

“I know very well what you’ve come to find, but I’ll not discuss your quarry or anything else until the agreed-upon fee has been paid.”

Emre swallowed hard. “I want a guarantee that the money’s going to do her some good.”

Adzin’s eyes narrowed as he craned his neck forward. “How old are you?”

“Sixteen, my lord.”

He looked Emre up and down. “Then perhaps you can be forgiven the insult. As Osman no doubt told you, I’m not in the business of finding anything until I know what you’re about, and the one you wish to find besides. My time is valuable. Now set the coins on the table or jump this ship, because either way I’m headed for the desert.”

Emre glanced sidelong at Çeda. After an unspoken agreement between the two of them, he took out two cloth purses from the larger leather one at his belt—months of meticulous savings from both Emre and Çeda—and dropped them onto a table that looked as if it had once served as a butcher’s chopping block.

Adzin picked up the smaller one first, the one filled with golden rahl. Apparently satisfied, he made it vanish into the folds of his kaftan. He then picked up the second, filled with lesser sylval, untying the drawstring with an intensity in his eyes that had been absent moments ago.

“All silver,” Emre said, “as instructed.”

As the ship turned, putting her on a heading that would take them toward the harbor’s entrance, Adzin motioned to the dusty, threadbare pillows on the opposite side of the table. Emre and Çeda sat while Adzin lowered himself onto a large, overstuffed pillow with an Adzin-shaped indentation at its center. Then, with a deftness that made it clear he’d done this many times before, he upended the contents of the second purse and laid out the coins on the table one by one, making sure the faces of the various Kings of Sharakhai were exposed. After stuffing the empty purse into the sleeve of his kaftan, he turned each of the King’s faces just so, though whether it was to do with the individual King or with the coin’s position on the table, Çeda had no idea.

“Now”—he ran a pasty hand through his lank hair and regarded Çeda with a look he might use on a head of garlic he hadn’t yet decided to buy—“this man you wish to find, tell me his name.”

“Kadir,” Çeda replied.

“His full name.”

“I don’t have it.”

Adzin’s beady eyes considered her, then he sniffed. “A proper name makes things easier but isn’t necessary.” He lifted his head to peer at her along his nose. “Why do you wish to find him, then, this Kadir?”

“The why of it isn’t your concern,” Emre replied. “I was told you could find those who needed finding. Now can you do it or can’t you?”

“Well, I do need something,” he said, as if the statement were self-evident. “Either give me his name, dear children, or tell me who he is.”

Emre and Çeda exchanged a look. They’d come this far. What was a few more steps down this dark, winding path?

“He was the manservant of Rümayesh,” Çeda said.

Adzin’s dark expression clouded further. “Rümayesh.”

Çeda nodded.

“She’s—” Adzin visibly collected himself. “She’s real, then?”

Çeda nodded again.

He licked his lips. “I was told nothing of this.”

Emre looked ready to cut in with a sharp rebuke over Adzin’s hesitance, so Çeda spoke quickly. “She will not be threatened in this. In fact, if all goes well, she may owe me, and those who helped, a great deal.”

Adzin considered, then gave a short nod. “You said he was her manservant. What did you mean?”

“Rümayesh has gone missing,” Çeda replied, “and Kadir went into hiding shortly after.”

“And how would you weigh this man?”

“Weigh him?”

Adzin sniffed again, peering at her in that strange way of his. “Tell me the sort of man he was.”

“Calm. Serious. Loyal.”

“What were the qualities of his eyes?”

Çeda had to picture it in her mind, how he’d stood in that opulent meeting room where they’d first met. “Dark brown. Deep. He had a way of assessing you quickly.”

“And the timbre of his voice?”

“Is this necessary?” Emre asked.

Çeda knew he was only trying to protect her, but she also knew how strange the ways of magic could be, so before Adzin could respond, she put her arm on Emre’s and said, “His voice was rich. Powerful. The voice of a man accustomed to having his orders followed.”

“And was it always so?”

Here, Çeda paused. What a strange question. How could she possibly know that? But when she thought about it, she wondered what sort of man he was before he’d met Rümayesh. He gave much to her, but had it always been so?

“I don’t think so.”

“Why?”

“I had the impression that Rümayesh chose him and brought him up, perhaps from the streets. There was a quality about him, as if he hadn’t been born to the luxury of the estate where we spoke and was wondering even then when it all might vanish.”

Adzin nodded. “Good,” he said. “Good.”

They continued for a time like this, the ship creaking as it heeled over the sand dunes, Adzin occasionally moving the sylval back into place when they slipped. Where they were headed Çeda had no idea. She only knew that Adzin was a man who, for an admittedly steep price, and for only the most carefully chosen clientele, would find things. She didn’t even know how he did so, only that Emre had found him, Osman had vouched for him, and she’d become desperate enough to try anything at this point.

She might have tried looking for Kadir herself, but she was so exhausted she’d started seeing things from the corners of her eyes, hearing snippets of conversations when no one was in the room. She’d never find a man like Kadir in her current state. No, as much as Adzin made her skin crawl, and as dearly as this voyage was costing her, it was the only course of action that might net her quarry before Rümayesh’s nightmares drove her mad.

Adzin’s questions ranged from general to obscure. At times he would pepper Çeda with them, and at others he would remain silent for minutes on end, staring at the coins arrayed before him. Through the small porthole to Çeda’s left she could see night falling over the desert. An hour into their voyage, without warning, Adzin flipped each of the sylval over to show the sigil of the King whose face appeared on the opposite side, then continued his questioning as if nothing had happened. After several hours, the ship finally began to slow. Then it coasted to a stop. Soon after there came a rattle of chain and a thump as the ship’s anchor stone dropped to the sand.

“Come,” Adzin said.

With deft motions he swept up the coins and slipped them back into the same purse Emre had given him, then he stood and slipped past them, leading them out from the cabin, along the passageway that even in the darkness made Çeda’s skin crawl, and up to the deck. The hulking deckhand dropped a rope ladder down to the sand, at which point Adzin, Çeda, and Emre climbed down and began walking toward a cluster of standing stones.

The sandy ground soon gave way to unforgiving rock. The evening wind was cool, but there was a strange scent upon it, like burnt wood and sulfur. As Adzin walked, he spoke. “There are still many of his creatures in the desert left behind from Goezhen’s more active days crafting life of his own. They are much fewer after the great cleansing before the elder gods left for the farther fields, but they can be found if one knows where to look.”

The twin moons were up, casting light bright enough to see two things: first, that there were giant stones set in a circle, and second, that within that circle lay a massive, gaping hole. Adzin led them past the stones, which were tall as trees, to the very edge of the hole. It dropped straight down, as if the elder gods had thrown a spear from the heavens to pierce the earth. The sulfurous smell became so unbearable Çeda was forced to cover her nose and mouth with her sleeve. Emre did the same. But Adzin merely kneeled at the edge of the hole and peered downward. What he might be looking for Çeda had no idea; it was so dark she couldn’t see a thing.

Adzin was holding something now—their coin purse, the one filled with sylval—and he was whispering words to it.

Çeda tried to speak, but the smell made her choke.

“Be quiet,” Adzin said, and continued to whisper. He dumped the coins carefully into his waiting palm. And then flung them with one swift motion, into the hole in the earth.

Emre gasped. Çeda’s eyes widened and she ran to the edge of the hole despite the caustic smell. By the light of the moons she could see the coins spinning down, each glinting like the surface of a tiny moonlit pond. Away they fell, further and further, until finally they were lost from view.

Emre bristled. “By the gods, why would you—”

“Silence now!” Adzin barked.

He peered downward, leaning so far out over the edge Çeda thought he might tip over and spin, end over end like one of those coins, and be lost to the world forever more. He remained like this for a long while, long enough for Çeda to give up on seeing anything of note from where she stood, and she backed away, if only to grab a few breaths of comparatively pure air. Emre did the same. The two of them stared at one another, silently questioning what it was Adzin might be doing, and further, what they’d gotten themselves into.

That was when Çeda heard it. The flapping sound.

It was soft but soon grew until it sounded like the washer women in Sharakhai as they snapped their clothes before laying them to dry on sunbaked rocks. Something large flew up from the dark abyss. The creature’s silhouette was difficult to discern against the gauze of stars, but it looked as though it had two sets of wings. Adzin raised one forearm like the falconer Çeda had once seen practicing for a show in the southern harbor. Moments later the creature flapped down and alighted on Adzin’s outstretched arm, and he walked to where Çeda stood, whispering to the creature as he came. When he stood before her, he motioned for her to raise her arm. She did, while some unspeakable worry ate at her insides over this strange, foul-smelling creature.

“They’re called ifin,” Adzin said, pushing his arm against Çeda’s until the ifin moved with ungainly steps onto Çeda’s arm. “This one knows you now. More importantly, it knows this Kadir of yours. It knows his scent from the clues you’ve given me.”

Çeda stared at the creature, her upper lip raising of its own accord. She felt like a wolf, hackles rising at something she couldn’t understand. The ifin had a sinuous neck and a sleek, eyeless head, like a lamprey she’d seen once in the bazaar. Where its eyes should have been were strange patches of mosslike skin. The ifin’s mouth looked like a funnel of bone-white teeth. Its four wings were like a bat’s, leathery with grasping claws at the end of each. “What by the gods do I do with it?”

Adzin laughed. “Why, you bring it to Sharakhai. The ifin will do the rest.”

Excerpted from Of Sand and Malice Made © Bradley Beaulieu, 2016