Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

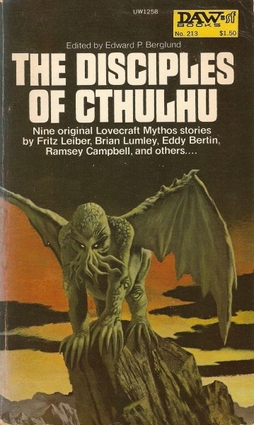

Today we’re looking at Fritz Leiber’s “The Terror From the Depths,” first published in Edward P. Berglund’s Disciples of Cthulhu anthology in 1976. Written 1937-1975 according to some sources, and entirely in 1975 according to others—can anyone solve the mystery? Spoilers ahead.

“The sea fog still wraps the sprawling suburbs below, its last vestiges are sliding out of high, dry Laurel Canyon, but far off to the south I can begin to discern the black congeries of scaffold oil wells near Culver City, like stiff-legged robots massing for the attack.”

Summary

Unnamed frame narrator introduces the following manuscript, found in a copper and silver casket of modern origin and curious workmanship along with two slim books of poetry: Azathoth and Other Horrors by Edward Pickman Derby and The Tunneler Below by Georg Reuter Fischer. Police retrieved the box from the earthquake (?) wreckage of Fischer’s Hollywood Hills home. Georg himself they discovered dead and strangely mutilated.

Georg Fischer’s narrative: He writes this before taking a drastic and “initially destructive” step. Albert Wilmarth has fled Fischer’s Hollywood Hills house following shocking discoveries with a magneto-optical scanner developed at Miskatonic University. The “hideously luring voices” of “infernal bees and glorious wasps… impinge upon an inner ear which [he] now can never and would never close.” He will resist them and write on though most future readers will deem him mad or a charlatan. A true scientific effort would reveal the truth about the forces that will soon claim Fischer, and maybe welcome him.

Fischer’s Swiss-born father Anton was a mason and stonecutter of natural artistry. He also had an uncanny ability to detect water, oil and minerals by dowsing. From Kentucky, Anton was drawn to the “outwardly wholesome and bright, inwardly sinister and eaten-away landscape” of Southern California, where he built the Hollywood Hills house. The natural stone floor of the basement he carved into a fantastic seascape dominated by giant squid eyes peering from a coral-encrusted castle, all labeled “The Gate of Dreams.”

Though born with a twisted foot, Georg roamed the snake-infested hills by day and sleepwalked by night. He slept twelve hours a day but remembered only a few dreams. In them he floated through tunnels seeming gnawed from solid rock, which he sensed were not only far underground but far under the nearby Pacific Ocean. Strange purplish-green and orange-blue light illuminated the tunnels and revealed carvings like “mathematical diagrams of…whole universes of alien life.” He also saw living creatures: man-length worms with translucent wings as numerous as a centipede’s legs and eyeless heads with shark-toothed mouths. Georg eventually realized that in dream HE himself inhabited a worm-body.

The dreams ended after he saw worms attacking a boy he recognized as himself. Or did they end? Georg had the impression his “unconscious night-wandering” continued, only stealthily, noticed not even by his conscious mind.

In 1925, on a ramble with Georg, Anton fell down a suddenly yawning hole in the path and died wedged beyond recovery. Would-be rescuers filled in the pitfall, which became Anton’s grave. Georg and his mother remained in the Hollywood Hills house. Though seemingly incapable of sustained attention and effort, Georg made a creditable showing in school and, as Anton had hoped, was accepted into Miskatonic University. He stayed only one term due to nervousness and homesickness; like Anton, he was drawn back to the brittle California hills. A stint at UCLA earned him a BA in English literature, but he pursued no steady work. Instead, perhaps inspired by Derby’s Azathoth, he self-published The Tunneler Below. Another inspiration was doubtless his renewed exploration of childhood paths, under which he was convinced there wound tunnels like those of his dreams.

Georg’s mother dies of a rattlesnake bite inflicted while she pursues her son with a letter—Georg’s sent the Miskatonic library copies of Tunneler, and folklore expert Albert Wilmarth is writing to praise it. Wilmarth also notes the odd similarity of Georg’s “Cutlu” with “Cthulhu,” “Rulay” with “R’lyeh,” “Nath” with “Pnath,” all references MU was investigating in a multidisciplinary study of “the vocabulary of the collective unconscious,” of strange links between dreams and folklore and poetry.

Wilmarth and Georg begin corresponding. Wilmarth mentions Lovecraft’s work, often based on Miskatonic’s eldritch discoveries, though, of course, highly spiced with Howard’s imaginative additions. Georg seeks out Lovecraft’s stories and is struck by echoes of his own dreams and experiences and thoughts. Could there be more reality in the fantasy than Wilmarth will acknowledge?

At last Wilmarth visits California, magnetic-electric “geoscanner” in tow. He’s been using it to map underground systems all over the country and is eager to try it on Georg’s hills. First, though, he checks out the “Gate of Dreams” floor. The scanner registers “ghost vacuities”—it must be acting up. It works better out on the trails the next day, showing that they’re indeed undermined by tunnels. Wilmarth theorizes that if Cthulhu and other extraterrestrials exist, they could go anywhere, perhaps seeping through the ground or under the sea in a dreaming half-state of being. Or maybe it’s their dreams that gnaw the tunnels…

Homeward bound, Georg and Wilmarth see what looks at first like a big rattler. It is, instead, one of Georg’s dream-worms! It runs for cover, they for the house. Later, Georg receives in the mail a copper-silver box containing a message from his father. Anton claims he had a special ability to “swim” under the earth in some extracorporeal form, hence his dowsing skill. Georg, too, is special and will be able to become “Nature’s acolyte,” as soon as he “bursts the gate of dreams.”

Meanwhile Wilmarth’s tried the geoscanner in the basement again. Something’s tunneled up from below, to within five centimeters of the stone! They must flee, but word of Lovecraft’s death convinces them to first take a daring risk: an experimental drug that should produce striking dreams in this haunted place. It does, at least for Wilmarth, who wakes in terror and rushes off in his car.

Georg remains to write his missive and put it in the copper-silver box for posterity. He’s determined to obey his father by sledgehammering the basement floor, the Gate of Dreams.

Perhaps he does. What we know is that an earth-shock strikes the hill-crest neighborhood, leaving the Fischer house a collapsed wreck. Searchers find Georg’s body at the edge of the rubble, along with his missive-containing box. His twisted foot is what identifies the corpse, for something has eaten away his face and forebrain.

What’s Cyclopean: The language jumps around a little as Leiber code-switches between his own style and Lovecraftian adjectival mania. That second style gives us: “hideously luring voices,” “crepuscular forces” (best writer’s block excuse ever), “decadent cosmic order,” and “horrendous revelations of the mind-shattering, planet-wide researches… in witch-haunted, shadow-beset Arkham.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Oswald Spengler, the narrator, and Cthulhu’s worm things believe that civilization rises and falls in cycles and that the Western world will become engulfed by barbarism.

Mythos Making: The hideous voices mutter of proto-shoggoths, the legend of Yig, Canis Tindalos, essential salts—a full catalogue of Mythosian references and stories.

Libronomicon: Edward Pickman Derby’s Azathoth and Other Horrors is notable for leading to at least two deaths: it attracts Waite’s attention to the author himself, leading to his deadly marriage, and inspires the poems that bring Georg the equally deadly attention of Miskatonic’s interdisciplinary folklore researchers.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Georg assumes readers will diagnose psychosis from his final manuscript.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

“Terror from the Depths” is a strange story: Leiber felt hypocritical critiquing others’ pastiche without having tried his own hand at it. As pastiche, it’s absurdly over-the-top. It invokes every one of Lovecraft’s late Mythos stories, several earlier ones of varying obscurity, and includes the existence of Lovecraft himself in the same world as Miskatonic and Cthulhu. (How the heck can you pronounce ‘Cthulhu’ monosyllabically?) To judge from other online discussions, it wins some sort of award for impossibility of synopsis; we’ll see if we can do better.

Catching all the Mythos references makes for amusing sport but lackluster art. However, “Terror” manages to avoid complete dependence on shoggoth rants, and Leiber’s original contributions to the mélange earn a legitimate shiver or three. The winged, eyeless worms, all mouth—that may simply be the dreams of a dark god given form and teeth—are pretty darn creepy.

Even more creepy, though, are the things he manages to keep under the surface. So to speak. Georg never does find out what work satisfies him so thoroughly during his half-day sleep. We never do learn whether his energies and motivation are drained by that work directly, or by some greater power that makes use of them, battery-like. But the idea that one’s potential might be sapped so permanently, for unknown purpose, without even knowing what you served or whether you did so willingly, is more terrifying than any number of worm-chewed faces.

In the end, Georg seems to serve willingly—or at least fatalistically. He expects new life as a winged worm. Both he and Wilmarth hint at comparisons to Innsmouthian apotheosis, the glories of Y’ha-nthlei. Endless tunneling as a Cthulhu dream-worm sounds a lot duller to me than immortality under the ocean, but what do I know? Maybe the worms have a rich life of the mind.

But there is a similarity to “Shadow Over Innsmouth” in that Georg’s ultimate and ultimately strange fate is an inheritance. His father learned, or had the innate ability triggered, to travel (Mentally? Physically?) beneath the earth, translating the beauty and awe found there into surface art. His carvings are reminiscent of the bas reliefs permeating Lovecraft’s ancient cities and documenting their histories. Like elder things and crocodile people, the winged worms also produce such carvings. Theirs, though, are abstractions: “mathematical diagrams of oceans and their denizens and of whole universes of alien life.” That I want to see!

The inclusion of Lovecraft himself, on top of the Lovecraftian references, seems at first one weight too much on a story already bent under a chorus of “It’s a Small Mythos After All.” However, setting the story at the time of Lovecraft’s death redeems this aspect. Something—a particular sort of knowledge, a way of shaping the fear it invokes—is passing away. It makes the story, like the strange white stone above Fischer Senior’s resting place, a memorial both unorthodox and worthy.

Anne’s Commentary

If I had to nominate one piece as the most exhaustive compilation of Lovecraftiana in the Mythos, it might be “Terror from the Depths.” Leiber began the story in 1937, a year after beginning a short-lived but intense correspondence with Lovecraft. He didn’t finish it, however, until 1975, shortly before its appearance in the anthology Disciples of Cthulhu. Interesting, since “Terror” marks Leiber, methinks, as a true Disciple of Howard.

You’d certainly end up with alcohol poisoning if you used “Terror” as a drinking game: Knock back a shot every time one of Lovecraft’s creations is mentioned. It would be easier to list the canon characters. locations, and stage properties Leiber doesn’t mention, but what the hell, here are some of the names he drops: Albert Wilmarth, Edward Derby, Atwood and Pabodie, Miskatonic University, Arkham, the Necronomicon, Henry Armitage and colleagues Rice and Morgan, Professor George Gammell Angell, Professor Wingate Peaslee, Henry Akeley, the MU Antarctic expedition, Robert Blake, Danforth, Nathaniel Peaslee of Yith brain-transfer fame, Harley Warren, Randolph Carter, Innsmouth, Y’ha-nthlei, the Shining Trapezohedron, Walter Gilman, Wilbur Whateley, Yuggothians, Nahum Gardner and his visitor the Color, Cthulhu, the underworlds of K’n-yan and Yoth and N’kai, Tsathoggua, Johansen the Cthulhu-Burster, whippoorwills as psychopomps, shoggoths, doomed Lake and Gedney, and Asenath (as liquescent corpse).

And that’s not even to mention the references dropped by the alluring insectile voices that continually harass Georg’s inner ear. So let’s mention just a few: protoshoggoths, Yig, violet wisps, Canis Tindalos, Doels, essential salts, Dagon, gray brittle monstrosities, flute-tormented pandemonium, Nyarlathotep, Lomar, Crom Ya, the Yellow Sign, Azathoth, wrong geometries. [RE: you can sing these sections to the tune of “We Didn’t Start the Fire,” if you try hard enough and are generous with the scansion.]

I’m out of breath.

Some definitions of pastiche differentiate it from parody thus: parody pokes fun, good-natured or the opposite, whereas pastiche expresses appreciation, is a homage. “Terror” is homage, all right. No coincidence, I think, that Leiber started the year of Lovecraft’s death. I don’t know why he didn’t finish it until decades later. A grief too new? At any rate, Lovecraft appears here twice.

He is first the actual writer, founder of a subgenre and frequent contributor to Weird Tales. I smiled to see that Leiber imagines Howard here as I do in my Redemption’s Heir series, as one of the Miskatonic-centered sages-in-the-know – in the know about the reality of the Mythos, that is. Also as in my treatment, the Miskatonic crowd lets hyperimaginative Howard publish his little pulp stories, because after all, who would believe them? And at best (or worst), they might prepare the general public for THE TRUTH, just in case they ever need to know. Like, say, if Cthulhu starts ravening in the squishy flesh. Wilmarth’s fond of Howard, a good fellow for all his literary excesses. He’s upset that, when he arrives at Georg’s, Lovecraft’s in hospital. Then the telegram comes from Arkham. Bad news, Lovecraft’s dead. Good news, the psychopomp whippoorwills didn’t get his soul, for their expectant cries trailed off into disappointed silence.

That puts Lovecraft on the same wizardly level as Old Man Whateley, which is quite the tribute. It strikes me, after finishing the story, that the epigraph from Hamlet must refer to the recently deceased Lovecraft, too: “Remember thee! Ay, thou poor ghost, while memory holds a seat in this distracted globe.”

Leiber also seems to conflate Lovecraft with his version of Albert Wilmarth. The two are pointedly similar in appearance, tall and thin, pale and long-jawed, with shoulders at once broad and frail-looking and eyes dark-circled and haunted. Both this Wilmarth and the real Lovecraft are prone to nervousness and ill-health, sensitive to cold, amateur astronomers and inveterate writers of letters. They both love cats and have one with an unfortunate name – Wilmarth’s is “Blackfellow.” Oh yes, and they both have brief but intense correspondence-bromances with a younger man, Lovecraft with Leiber and Wilmarth with Georg. Georg himself, under the influence of the dream-inducing drug, sleepily notes that Wilmarth and Lovecraft strike him as the same person.

Or he almost notes it, because Wilmarth (Lovecraft?) cuts him short in alarm. Passing strange little conceit here!

Georg himself is an intriguing character. Though he’s always spent half his time in sleep, he supposes he doesn’t dream. Unless he does, but he (or something else) hides it from his conscious mind. His situation resembles Peaslee’s – he may be largely amnesic to his persona-transfer to an alien body, here nightly repeated through his entire life rather than during one five-year “sabbatical.” In the end, Georg hopes to earn a welcome from the tunneling worm things, say, a permanent body-transfer. Huh. Could be Leiber conflates the Yith with the Yuggothians, since Georg undergoes a radical front-brainectomy, maybe with the transfer of his cerebral matter to the devouring worms rather than to a storage canister.

One last observation: Leiber succeeds at elevating the arid, spongy landscape around Los Angeles to a Lovecraft’s New England pitch of inextricably intertwined beauty and menace. It’s true, I guess, that Cthulhu and Company can seep their way across the continent, no problem!

Next week, Antarctic adventure and ancient aliens in Holly Phillips’ “Cold Water Survival,” which you can find in Paula Guran’s New Cthulhu anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

As a native Angeleno, I must say that Leiber does a tremendous job evoking the city. It may help that the places he goes into the most detail describing are those that hadn’t changed much in the nearly four decades between the setting and the (final) writing. But then, Leiber is usually pretty good at evoking place, from Lankhmar to San Francisco.

Based on very little, I tend to connect the worms here with Lumley’s Cthonians (and also with graboids, of course). That may be the influence of Chaosium and Sandy Petersen, who I think did draw an explicit connection.

I also think there’s a strong Yuggothian connection, probably due to the confluence of Wilmarth and the strong insectile imagery used for the voices Georg hears. Leiber seems to have been fascinated by the Mi-Go. Consider also “To Arkham and the Stars”, which also features both Lovecraft and Albert Wilmarth.

And Ruthanna’s aside to Anne’s listing of Lovecraftiana has earwormed me big time. I think there are some definite filk possibilities there.

Hmm. I thought Georg and his fate made for an interesting if disorganized story. Was he devoured? Or downloaded? Or perhaps something exited his skull from the inside?

But I feel a bit concerned when remembering the existence of The Burrowers Beneath. Would be embarrassing if the actual backstory for Terror turned out to be “Leiber often fantasized that some Mythos monstrosity would come along and eat Brian Lumley’s brain…”

I’d sure like to see what you do with “Our Lady of Darkness”. Also, “A bit of the Dark World”.

Leiber’s correspondence about this story was collected in an essay by Berglund, “The Shadows Over Fritz Leiber”.

It was originally an attempt to write the story “The Burrower Beneath” mentioned in “The Haunter in the Dark”. Leiber wrote about 4-5 thousand words in March 1937. Leiber had mentioned his attempt at a Lovecraftian story in several reminiscences of Lovecraft, so when Berglund was compiling “Disciples” he contacted Leiber about it. Leiber only meant to add a couple of thousand words to complete it but instead extended it by at least 10,000 words. He viewed it as a collaboration between the Leiber of 1937 and 1975. By 1975 Brian Lumley had taken that title for one of his stories, so Leiber retitled the piece “Terror from the Depths”.

I’ve assumed the lead character Georg Reuter Fischer is named after two of Leiber’s closest friends from the 30s Georg Mann and Harry Fischer (co-creator of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser), and Reuter was leiber’s middle name. Almost every place across America mentioned in the story was visited by Leiber. The architect father is a distortion of Leiber’s actor father building his own homes. I’m sure there are many more autobiography allusions tucked away in the story

Not directly related to this post, but I recently read Robert W. Chamber’s <i>In Search of the Unknown</i> (published in 1904, later than <i>The King in Yellow</i>). I don’t know if anyone has raised this before, but the first section of the book, about the harbormaster, would fit very well into this series. The rest of the book was mostly pretty dreadful and perhaps best ignored.

I also came across a webpage (http://www.kpfahistory.info/black_mass_home.html) with free links to a series of short radio plays produced in the early 1960s of various wierd stories by authors such as Lovecraft, Dunsany and Poe. Might be of interest to some readers.

I want to see “The Gate of Dreams.” And a picture of those worms.

(How the heck can you pronounce ‘Cthulhu’ monosyllabically?)

It involves a LOT of phlegm!

Consider also “To Arkham and the Stars”, which also features both Lovecraft and Albert Wilmarth.

That was a very sweet tribute to HPL, and a great subversion of the typical ‘Mythos’ tropes. Maybe those tentacled horrors aren’t so bad.

I also was struck by the beautiful evocation of geography that Leiber evoked here and in ‘Our Lady of Darkness’. Leiber’s description of the rotted-out hills of Hollywood remind me of CAS’s evocation of the beautiful desolation of Crater Ridge in ‘City of the Singing Flame’. I also like Leiber’s mention of Simon Rodia and his Watts Towers. It’s these little insertions of real detail that lend these wild tales some versimilitude.

Ordinarily, the whole ‘Lovecraft as a character’ trope drives me nuts (I’m looking at YOU, Derleth, flogging your edition of The Outsider and Other Tales), but I didn’t mind it here, nor the weird conflation of Wilmarth and Lovecraft. I guess I have such a love of Leiber’s fiction that I’m willing to cut him some slack- when Leiber has fun, we all have fun.

“The Terror from the Depths”, while not Leiber’s best foray into this subgenre as a horror store, remains entertaining and is a fine way to celebrate the work of a mentor and a friend.

@2: devoured and downloaded? I am reminded the way flatworms are supposed to learn from other flatworms by devouring their bodies. I rather fancy the notion of some essence of Cthulhu/whatever seeping through the body of the American continent through innumerable tunnels, like the fine threads of a fungus spreading through a loaf of bread.

@6: Well, here’s Deviantart’s effort: http://www.deviantart.com/art/Brain-Worm-188374582

That’s pretty good.

Matthew,

Where can I find the essay by Berglund?

Berglund’s article was originally published as “The Burrowers Beneath” in “Crypt of Cthulhu #66”, 1989 and then reprinted as “The Shadows Over Fritz Leiber” in “Fantasy Commentator” Summer 2004

I remember being impressed by Leiber’s reference to the “narrow dark roads of West Virginia”. If you get off the Interstate here in the Mountain State, you quickly realize that Leiber must have been here, because he’s absolutely nailed it.

I also like the fact that the name Cthulhu is monosyllabic. So for Leiber, it was an alien noise with NO connexion to any earthly language. The winged worms, which are Cthulhu’s dreams made manifest (shades of the old film FIEND WITHOUT A FACE!) are a clever invention, and one that shows there’s plenty of weird in the Mythos well yet.

Right, so I happened to be looking at some old posts just a couple days ago and saw Ruthanna suggesting that Anne’s list of Outer God names matches up pretty well with “We Didn’t Start the Fire”. Turns out that HPL/Billy Joel mash-ups are a thing. Not for the above-named song, but it seems that the early HPL poem “Nemesis” scans perfectly with “Piano Man”. Also in the comments at that link, there’s a video of someone who turned the Plain White T’s “Hey There Delilah” into “Hey There Cthulhu”.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 16: So I heard! And now I can’t un-hear…

Police retrieved the box from the earthquake (?) wreckage of Fischer’s Hollywood Hills home.

I’m now conflating this with Heinlein’s And He Built a Crooked House. SF is just terrible for Hollywood housing values.