I remember excitedly sitting down in the theater to watch The 13th Warrior when it came out in 1999. As a medievalist I get pumped about most big-budget quasi-medieval films (and, yes, a lot of low-budget ones, too!), but this one had me more excited than usual.

First, it was directed by John McTiernan. Despite some occasional career blunders, he’s helmed both Die Hard (1988) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). That’s good for something.

Second, the movie was based on Michael Crichton’s Eaters of the Dead, a novel that was, in turn, based on both the great Old English epic Beowulf and the very real account of Ahmad Ibn Fadlan’s embassy to the Volga Bulgars on behalf of the Caliph of Baghdad in the year 922. As a Muslim outsider, Ibn Fadlan recorded much of what he saw with what was, at times, a kind of horrified fascination. The resulting book (and thus the other source Crichton used) is called the Risala, and it’s most famous for Ibn Fadlan’s eyewitness account of the ship-burial of a king among the Rus—a band of Vikings who plied their trade along the Volga River and (fun fact alert!) ultimately gave their name to Russia.

As a conceit, Crichton’s plot is a fun one. He accurately relates Ibn Fadlan’s real account up to that famous burial, but then he smoothly shifts to fiction: the new leader of the Rus is a man named Buliwyf, and he immediately learns of a dark and ancient threat menacing a tribe to the north. An oracle suggests that thirteen men be sent in response, and that the thirteenth man cannot be a Viking. Ibn Fadlan goes along with the party, and an adventure begins—one that’s a rewriting of the story of the hero Beowulf (Buliwyf, of course). For the record, this conceit is both terrifically clever and utterly impossible. To cite but one reason, our sole surviving copy of Beowulf was written at the end of the tenth century, which totally works for Crichton’s re-imagining—but the story it relates takes place some five centuries earlier, which doesn’t work at all.

Regardless, like I said, I went into the theater pretty excited.

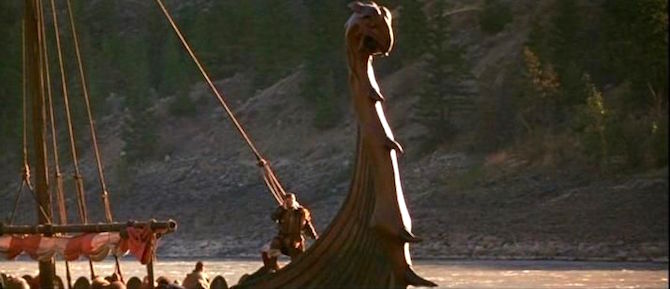

Alas, the opening shot nearly wrecked my excitement. It’s Vikings on a longship in a storm …laughing.

Not chuckling in the sort-of gallows humor way that I could see a real person doing—”Haha, welp, we’re all clearly gonna die now”—but full-on and deep-throated belly laughter in a way that no one but fake Vikings in movies ever do.

On a ship. In a storm.

The only man not engaged in uproarious merriment aboard the vessel is a miserable-looking Antonio (“How do you say? Ah, yes”) Banderas, who sits in the drenching rain, playing the role of a dejected puppy dog an Arab tag-along to this band of merry fellows who have apparently just heard the greatest joke ever told. In voiceover, he introduces himself as Ibn Fadlan and notes that “Things were not always thus.”

And then, remarkably, the movie gets worse. We’re thrust into a confusing flashback sequence relating how Ibn Fadlan was once a court poet in Baghdad who fell in love with another man’s wife—which is a cool story for the few seconds of screen time it requires in order to serve as an overly complex reason for Ibn Fadlan to be sent away to serve as an ambassador to the land of the distant Volga Bulgars.

And here we get a helpful map overlay for the geographically disinclined.

Wait…does that map place the city of Baghdad between the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea, somewhere around modern-day Vladikavkaz in Russia? Sure does! That’s around 700 miles north of its actual location in Iraq.

Turns out it isn’t the audience who needs a damn map.

And then, even before this map of alt-fact Earth is done fading out, Ibn Fadlan’s voiceover informs us that he next met some dangerous Tartars.

Wait…the Tartars were marauders of the 13th century, not the 10th. So, um …

Ignoring my attempts to get this timeline to make sense, the movie presses on, and Ibn Fadlan’s delegation is indeed beset by dangerous Tartars—which is cool for the few seconds of screen time it requires in order to serve as an overly complex reason for Ibn Fadlan to run toward a river where he and his company see a longship.

This leads Ibn Fadlan and his fellows to worry about whether the newly discovered Norsemen will kill them—which is a cool story for the few seconds of screen time it requires in order to have the delegation go just a bit further along the river to where they run into an encampment of the Volga Bulgars…

…which is where the damn movie needed to start, because literally the only thing that we need to know about all of the preceding is that Ibn Fadlan is a Muslim ambassador to these folks.

So, if you want to watch this movie—and you should, because I sorta guiltily love it—you’ve got to skip the first 3 minutes and 45 seconds of it.

Not a mistake there, by the way: they packed all that nonsense into less than four minutes of screen time. I’d say that’s a record for hurting my poor medievalist sensibilities, but I’m still recovering from my ill-fated drinking game with quite possibly the worst Viking movie ever made.

Part of the reason you should nevertheless watch The 13th Warrior, though, is that there are moments like the next sequence, which is one of my favorites in the film because it shows awareness of a very real and important element that most movies ignore: language.

Ibn Fadlan speaks Arabic, you see. The fine Viking fellows he now meets in the main tent of the encampment—a tent filled (sigh) with seemingly constant uproarious laughter and drinking through beards—don’t speak that language at all. (What they are actually speaking, in fact, is Norwegian, which is a descendant of Old Norse tongues and convenient for the filmmakers because it was the native language of many of the actors.)

Luckily for him, Ibn Fadlan has a companion with him named Melchisidek (played by the wonderful Omar Sharif) who begins trying some of the different languages he knows on various bearded fellows in the crowd. One of them hears him speaking Greek and so leads them to a Viking named Herger the Joyous. This character will proceed to totally and utterly steal this and every other scene he is in, and I hereby declare that the actor, Dennis Storhøi, is sadly underused by Hollywood.

Anyway, Melchisidek is trying to find their king so that he can present Ibn Fadlan to him, and their first conversation goes like this:

Ibn Fadlan (in English, here passing for the protagonist’s Arabic): Try Greek.

Melchisidek (in Greek): Hegemona hymeteron? Basilea hymeteron?

Herger the Joyous: ::half-drunk stare::

Melchisidek (in Latin): Uestrum legem?

Herger (in Latin, after a beat): Noster Rex! Tabernaculo.

Melchisidek (in English): He says their king is out there in that tent.

Herger (in Latin): Non loquetur.

Melchisidek (in English): He says the king will not speak with us.

Herger (in Latin): Non loquetur, quia mortuus est!

Melchisidek (in English): Apparently, the king will not speak to us, because he is dead. This is his funeral.

Buliwyf (in Norwegian): Herger, hvem er den fremmede?

Herger (in Norwegian): Det er en Araber fra Baghdad.

No Common Tongue bullpucky here, folks! It’s even got natural errors. Melchisidek’s Greek, “ἡγεμόνα ὑμέτερον, βασιλέα ὑμέτερον,” by which he is apparently trying to say “Your chief? Your king?”, is incorrect grammar (this is not his native tongue, you see). And his Latin “Uestrum legem” doesn’t mean “Your king’ but instead “Your law,” an easy mistake for “Your law-giver.” This is the reason it takes Herger a moment to understand what he’s asking, and the reason he corrects Melchisidek with correct Latin (“Noster Rex”) when he does.

This kind of thing goes on until Ibn Fadlan heads off as the titular thirteenth warrior with Buliwyf and his Viking pals. Oh man. I love it.

But wait! There’s more! Finding himself now without his translator Melchisidek, Ibn Fadlan next spends night after night watching and listening to his companions talking (and, of course, laughing) around the campfire until he learns enough to respond to one of their jokes at his expense.

Study abroad language immersion for the win, kids!

This sequence, too, is marvelous. Through cut scenes we watch as the men around the campfire go from all-Norwegian to mostly-Norwegian-but-a-little-English—McTiernan uses repeat cuts, zooming in on their mouths to show Ibn Fadlan’s focus—to mostly-English to this moment when Ibn Fadlan reveals his new language abilities:

Skeld the Superstitious: Blow-hards the both of you. She probably was some smoke-colored camp-girl. (points at Ibn Fadlan) Looks like that one’s mother!

Ibn Fadlan (speaking slowly in English, now passing for the protagonist’s newfound Norwegian): My mother …

Skeld: ::stares at him in shock::

Ibn Fadlan: … was a pure woman … from a noble family. And I, at least, know who my father is, you pig-eating son of a whore.

Oh maaaaaan. With the pork-prod at the end, too. Boom. Medieval mic drop. (Watch it here.)

I know some reviewers gripe about this sequence, complaining that you can’t learn a language so quickly. To that, I say that no, apparently you can’t. But some folks over the course of a week of immersion really can pick up more than enough to get by. Plus, you know, at least the filmmakers are actually trying here. They’re paying attention to the problem of language. And I love it.

As it happens, McTiernan also paid attention to these details in The Hunt for Red October, too. Get past Sean Connery’s Scottish Russian and you’ll see a great scene in which a KGB officer starts to question Connery’s sub-captain—both of them speaking in Russian with subtitles. At one point the officer picks up a Bible that the captain has been reading, and he starts to read a verse from the Book of Revelation. The camera zooms in on his mouth as he speaks Russian … right up until he hits the word “Armageddon.” Then, without skipping a beat, the officer completes the verse in English as the camera zooms back out. Voilà, our Russians will now speak English (at least until the final scenes where they’re joined by actual English speakers), and we have a movie that’s easier to follow. That the filmmakers flipped it on “Armageddon,” the word common to English and Russian and the threatening theme of the Cold War itself, is just perfection.

But back to the 5th/10th/13th century.

No. Scratch that. It’s also the 16th century since one of the Viking warriors is wearing a Spanish conquistador helmet called a morion and another has a peascod breastplate. Aaaaaand there’s also a Viking in what looks like an 18th-century walking kilt. One of them has a Roman gladiator helm that’s iffy but at least sorta vaguely theoretically possible, and the whole horse-size thing is completely flipped around since the Arabs had the big horses and the Vikings had the wee ones, but, you know, I’ve got to set my historical brain aside at some point and just watch the film.

So, anyway, back to the 5th/10th/13th/16th/18th century.

Looking past all the historical mistakes (and the logistical insanity of that horse herd at the end), The 13th Warrior is actually a fun and well-done film. Even if the amazing language sequences weren’t there, the filmmakers still made a movie with some great visual moments, a good score (two of them, as it turns out), some tight battle sequences, a solid plot, and some truly enjoyable characters. The protagonist in particular undergoes a remarkable journey from a self-important man to one who, the moment before a dire battle, can earnestly make this prayer:

Ibn Fadlan: Merciful Father, I have squandered my days with plans of many things. This was not among them. But at this moment, I beg only to live the next few minutes well. For all we ought to have thought, and have not thought; all we ought to have said, and have not said; all we ought to have done, and have not done; I pray thee, God, for forgiveness.

Matching such moments, I think, is acting that is superb for this kind of film. Storhøi’s Herger, as I said, steals every scene he’s in. And Banderas, leaving aside the fact that his accent is Spanish, makes for a great outsider in Ibn Fadlan. One final sequence is (I think) perfect, as the men join in a traditional Norse prayer—with Ibn Fadlan now perfectly woven in:

Buliwyf: Lo, there do I see my father. Lo, there do I see…

Herger the Joyous: My mother, and my sisters, and my brothers.

Buliwyf: Lo, there do I see…

Herger: The line of my people…

Edgtho the Silent: Back to the beginning.

Weath the Musician: Lo, they do call to me.

Ibn Fadlan: They bid me take my place among them.

Buliwyf: In the halls of Valhalla…

Ibn Fadlan: Where the brave…

Herger: May live…

Ibn Fadlan: …Forever.

That’s good stuff, made even better by the fact that Ibn Fadlan, in the grander meta-fictional conceit of this, will be the man to write Buliwyf’s story and set off the chain of tales that will leave him immortalized in Beowulf.

All in all, The 13th Warrior is definitely one of my go-to “medieval” films despite the many historical issues. Don’t be surprised to see, when I get around to finishing it, that this film ranks very high on my list of the best film adaptations of Beowulf.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Literature at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy series set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven and its sequel The Gates of Hell, is available from Tor Books.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Literature at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy series set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven and its sequel The Gates of Hell, is available from Tor Books.