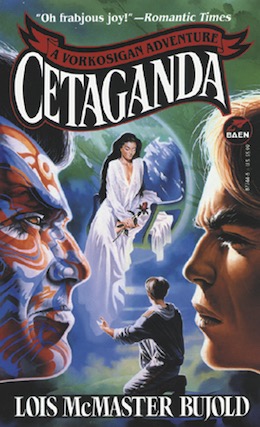

Chapters 2 and 3 of Cetaganda posed a reading dilemma—are they best read as intergalactic space opera mystery adventure, or is it fair to scrutinize them as though they were the reading material for an advanced seminar in intergalactic race, class, and gender issues? I don’t think these readings are mutually exclusive, but on this occasion, they didn’t fit into a single blog post either. So here we are at Cetaganda, chapters 2-3, the encore presentation!

Later in his life, Miles Vorkosigan will periodically point out that fish don’t notice the water. His comments on this aquatic situation are usually intended to point out something about heightened levels of security and/or political power, but they are equally true of race, class, and gender issues, which are often invisible to those whose position in these hierarchies is relatively privileged. Miles, for example, is a Vor male. While his fragile bones deprive him of some of the status associated with his class and gender, Miles is unquestionably a member of the Barrayaran elite, and consequently has access to economic resources, medical care, political advocacy, and opportunities for meaningful work that are not widely available to most of the Barrayaran population.

Miles’s trip to Cetaganda, which he makes as a representative of his government, is both an example of his accrual of privilege and an opportunity for a demonstration of how a variety of intergalactic cultures create and interact with forms of status that confer or deny privilege. From Miles’s own perspective, the privileges that are most significant are the ones he lacks—during the reception at the Marilacan embassy, Miles is preoccupied with the privileges that intergalactic society confers upon his cousin Ivan as a result of Ivan’s relative health and good looks. Miles is actually slightly closer to the locus of formal Barrayaran political power (the Prime Minister of the Council of Counts, the Imperial Campstool) than Ivan, but does not notice because these advantages are undesired, and are not useful in Miles’s efforts at romantic conquest.

Although he is primarily invested in his own selfish ends, Miles also uses casual party conversation to propose greater access to career opportunities for Barrayaran women. The Vervani attache, Mia Maz, points out that understanding women’s etiquette is vital to understanding Cetagandan society and politics. The Barrayaran embassy has no one to take on the challenge of Cetagandan women’s issues because these are not discussed with men, and Barrayar does not have any women in its diplomatic corps who have sufficient experience to take on this work. This situation is crippling to both the careers of Barrayaran women and to Barrayar’s efforts to advance its interests in intergalactic diplomacy. In pointing out that experience has to be gained, and Barrayar will have to create experienced female personnel from the ground up, Miles is carrying out a form of advocacy that I presume he learned at his mother’s knee. Although his proposed solution may appear obvious to readers, it is surprising and new to Ambassador Vorob’yev. This demonstrates the ways in which Barrayaran assumptions about gender limit Barrayaran women’s access to training that is generally available to Barrayaran men.

Miles’s abortive efforts to flirt will bring him into contact with the Cetaganda Ghem, a military class that ranks below the Haut. At this point, Miles’s knowledge of the Ghem and the Haut is insufficient for him to do more than note that some Ghem women are strikingly beautiful. Lord Yenaro demonstrates the problems facing male Ghem who elect not to enter military service. Yenaro struggles to find patrons for his artistic endeavors. He is unable to support himself through these endeavors, but his rank prevents him from seeking less exalted forms of paid employment. His efforts to remedy his financial difficulties through respectable means make him vulnerable to the schemes of the higher-ranking Ghem.

Yenaro’s conversation will remind readers of the importance of dress in Cetagandan culture. Ambassador Vorob’yev has already noted that it is nearly impossible for Barrayaran visitors to discern what is appropriate attire for the wide variety of events in Cetagandan society, and that wearing uniforms helps deter criticism about being inappropriately dressed. Lord Yenaro provides a sample of this criticism in his conversation with Lady Gelle, who he criticizes for wearing a perfume that clashes with her gown. I know why the Haut ladies wear force bubbles, ya’ll. Being completely shielded from the eyes of impecunious-yet-snarky Ghem-lords, and thus spared their snide commentary, is a compelling reason to ride around in a float chair with a force screen that also makes it difficult for witnesses to identify you in a court of law.

We will later discover that the force bubbles can sometimes be set to become COMPLETELY INVISIBLE and that, in the hands of a skillful operator, they can also coast through the air like those sky-diving suits that make people look like flying squirrels. The Haut ladies we will encounter in Cetaganda seem to take their hair and clothing (and probably perfume, though Miles tends not to notice) very seriously. Deep in my heart, though, I do believe that sometimes they wear bunny slippers. Miles will later wonder if the bubbles can be used to cover up criminal activity, and while I think this is indicative of a tendency towards a culturally insensitive level of suspicion about practices that are deeply meaningful to other cultures, we will discover that they can. If you can smuggle a corpse in those things, I imagine they are also convenient for attending to the needs of a breastfeeding infant while attending social gatherings.

At no point in the course of sixteen Vorkosigan books and assorted other material have we ever seen a Cetagandan woman of any social class tend to an infant, or discuss the needs and strategies associated with attending to small children. And that’s odd, for a series that deals so extensively with human reproduction. The haut women are intensely engaged with reproduction on a population-wide scale, with the needs and well-being of the population as a whole being far more important than individuals or bonded pairs of parents. Uterine replicators feature heavily. I don’t know when Cetaganda was settled, and if that occurred late enough for the first colonists to pack uterine replicators along in their baggage. Did they adopt their centrally-managed approach to reproduction before or after this technology was introduced? How did that go?

However it may have gone then, how it goes now involves the Ba. I am deeply concerned about the Ba. I’m not a fan of societies that breed asexual, non-reproducing slaves (or any kind of slaves) as genetic experiments. I’d like to see what the Quaddies think about that.

Aged 22 and educated by Barrayar’s Imperial Military Academy, neither Ivan nor Miles is in any way prepared for the advanced seminar in intergalactic race, class, and gender issues. Next week, we’re going to get back into the intense Cetagandan social whirl that they have been thrown into. Despite the significant role that Cordelia and Alys have played in their lives, the boys are basically staggering around in the dark. They are, at best, occasionally reminded of the existence of flashlights.

Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer teaches history and reads a lot.