I don’t want to inflict vertigo on you, but in this installment of a deeper dive into my Crash Course in the History of Black Science Fiction we fly from the far past of 1887 and “The Goophered Grapevine,” to a novel of the nearly now.

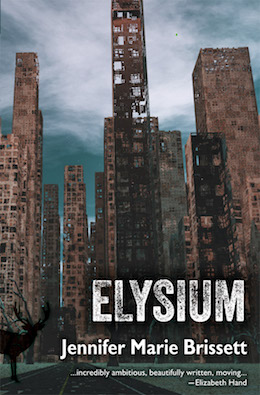

Elysium by Jennifer Marie Brissett could be categorized as the hardest of hardcore science fiction: aliens, spaceships, supercomputers–it has them all. Yet the lasting impression left by this brief but monumental 2014 novel is one of ethereality. Empires fall, towers melt into the air, and in the end only the most beautiful of ephemera abide: love and stories.

WHAT GOES ON

In a series of vignettes separated by ones and zeros and DOS-looking command strings, a protagonist named variously Adrian and Adrianne, of shifting gender and age, loses and finds and loses again the person they love. This loved one, whose name and gender and age also change, is sometimes Adrianne’s brother or father, sometimes Adrian’s pregnant wife or AIDS-stricken husband. And sometimes they’re someone else: Adrian/Adrianne loves Antoinette/Antoine through a multitude of scenarios. These vignettes’ action and dialogue overlap and in part repeat themselves, advancing gradually into grimmer and grimmer territory. Beginning with an accidental injury to Adrianne’s head that seems to occur beneath one of New York City’s ubiquitous scaffoldings, Brissett transports readers from that recuperating woman’s sad apartment, site of her lover’s inexplicable disenchantment with their relationship, to a vast underground city, to the post-apocalyptic ruins of a museum, to other even stranger locales.

Over and over again, owls and elks appear in mysterious and completely inappropriate circumstances. A green dot glows constantly in the sky. Along with continuity glitches such as autumn’s advent in the middle of high summer and the return to life of those indisputably dead, these recurrences delicately undermine each episode’s narrative reliability. Each until the last.

WHAT’S SO BLACK ABOUT IT

Touchstones with the black experience abound in Elysium. At the most superficial level many of the characters’ physical traits–skin color, hair texture, facial features–are described in ways that tell readers they are black. And there are textual references, too, as when Adrianne follows the green dot through spectral city streets “like the slaves of old the northern star.” Digging slightly deeper you’ll find one version of Adrian musing about the protection from an alien-induced plague his high melanin count gives him. In this instance blackness is not only present, it’s a plot point.

Earthlings’ interactions with different passages’ differently rendered alien invaders also model facets of the black experience. Elysium’s depiction of the alien colonizers’ implacable elimination of anyone in their way will be familiar to all people of color. Denying others’ humanity is yet another imperialist tactic used around the globe, echoed here by the pest-control-like tactics apparently employed against all humans. However, their wider resonance doesn’t make these elements of the book any less relevant to blacks: the particular source of them in Brissett’s black heritage lets its outpourings become universal but stays anchored in the hurt and defiance of the ever-present African-descended ancestors many of us share.

Finally, there’s Elysium’s connection, deliberate or not, with the concept of survivance. As noted in the linked article, survivance is a deliberately ambiguous term first used by Native American critical theorist Gerald Vizenor. A step beyond mere survival, survivance entails adaptation. It implies growth and change, not just preservation, and renounces the subject-weakening acceptance of a history of victimization.

Invisibly coded into Earth’s atmosphere, the fictional computer whose machine-language interruptions punctuate Brissett’s story contains a record of our whole world’s culture. History, art, science–everything is archived here. But the archive isn’t meant, as Adrianne rebukes an alien eager to explore it, “for the likes of you.” It’s meant for other humans, as a tool with which to build and rebuild the essence of our evolving lives.

WHAT’S TO LOVE

“Ambitious” is the word most frequently used to describe Elysium. In form and topic, that description is apt. Intimately detailed scenes portray a galactic epic superbly. Sublimely.

This book has a poem’s grace. That is to say, though made of words, it dances. Spare yet gorgeous, Elysium’s turns of phrase require no decorative enameling, no armature or exoskeleton to hold them up or flatteringly frame their substance. Rhythm and repetition strengthen Brissett’s message about love’s enduring power. Rhythm and repetition help; ultimately, though, the words she uses are exactly perfect, and being perfect, they’re all that’s needed.

WHY IT’S SO IMPORTANT

When asked to list African-descended science fiction, fantasy, and horror authors, readers will often come up with a very small number of names. Usually Samuel R. Delany gets mentioned, and usually Octavia E. Butler. Resourceful people are able to cite a few others without resorting to internet search engines. But there are many more, as my original Crash Course post made clear.

Jennifer Marie Brissett is one of them. Elysium is her debut novel; she has also written several short stories. As one of an emerging crew of African Americans working in the imaginative genres, she’s in the vanguard of a literary movement, a gloriously gifted voice raised in the newly swelling choir of speculative griots. As a living author currently working in the imaginative genres, she thrives on audience support. So let’s give it to her.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

I ADORE this book. It blew me away when I first read it and I’ve bought several extra copies to give to friends. It is so beautifully written and so haunting. I’d love for it to receive more attention – great to see it discussed here.