On International Women’s Day, several of the best writers in SF/F today reveal new stories inspired by the phrase “Nevertheless, she persisted”, raising their voice in response to a phrase originally meant to silence.

The stories publish on Tor.com all throughout the day of March 8th. They are collected here.

Astronaut

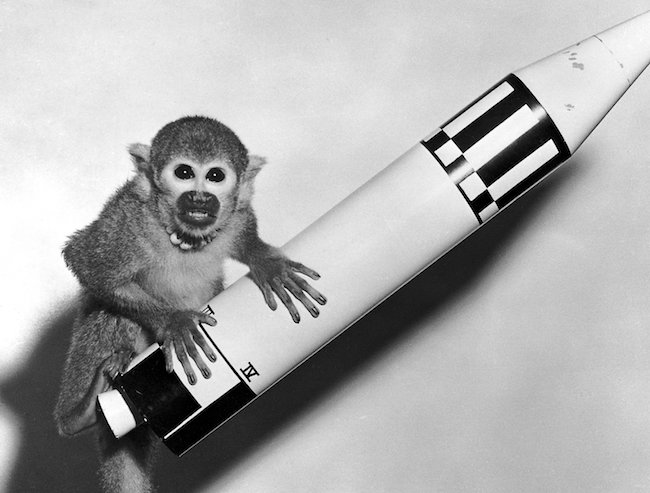

She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted. Miss Baker was on a mission to defy gravity.

It was 1959. The world was pencil skirts and kitten heels, stenographers following scientists in suits, and it was no different in Florida. Miss Baker had thirteen competitors for the single spot on the voyage, and they were all male.

If you keep trying to rise, one of them whispered to Miss Baker during training, no one will ever want to marry you. No one likes a girl who tries to climb over everyone else. To that, she spat in the dust, and went to find herself some lunch, doing stretches all the way. She had no time for their shit.

The Navy thought they’d chosen her randomly, but she’d been planning this since her birth in Peru and childhood in Miami, placing herself in line for a path to the stars, each moment of her existence a careful step toward a shuttle.

By day, the academy was all lustful glances, pinches, and indecent proposals. By night, Miss Baker slept with gritted teeth, curled tightly into her bunk. She was busy, slowing her heart rate, stabilizing her blood pressure, meditating, in preparation for her voyage. The training was necessary. There’d been seven failed astronauts before her, all but one of them named Albert. They’d died of suffocation, parachute failures, and panic. If any of the Alberts had seen the world from above, they hadn’t told anyone about it. The most recent Albert had gone into space with a crew of eleven mice, but died waiting for his capsule to be retrieved. What had he told the mice? No one knew.

But Miss Baker was no Albert. She was herself.

She lowered her heart rate still more, impressively. The others were being eliminated. One by one they went, cursing her and insisting that she’d be alone forever, that she would never find a home or a husband.

You’ll die, they told her. You’ll fall into the ocean and they’ll never find you. Or you’ll fly into the sun. You’ll die alone eaten by fish, or you’ll die alone eaten by birds. You’re not even pretty, they said, as a last resort, but Miss Baker did not care.

She hummed to herself in her isolation capsule as her competition melted down, hearts racing, teeth chattering.

Assssstronaut, hissed her second-to-last competitor, as though her dreams could be used to taunt her. He raised his fist to throw something foul, but she was too quick, up and over his head, doing a backflip on her way into the next room.

Pendejo! she shouted over her shoulder.

He didn’t have her discipline. If he went up, he would die of fright. None of the women of Miss Baker’s family suffered from nerves. They’d climbed together up the highest volcano and looked into the boiling belly of the earth.

She felt a grope on her way to the galley, kickstepped into the groin of the grabber, and hightailed into her own quarters to practice weightlessness.

Astronaut, she whispered in her bunk. Astronauta, she said, in Spanish. Then she said it a third time, in her mother’s tongue.

The next day, her last two competitors were dismissed.

The supervisors commissioned a shearling flight jacket and a flight helmet lined with chamois, a necklace with her name on it, and a national announcement that she’d been chosen to rise.

Miss Baker remembered her first sight of destiny. She’d seen a shuttle go up, from a window facing the Cape. She’d stood at that window, staring, as something small and bright broke the rules of the known world, and from then on she’d been certain.

Astronaut.

Now she was that bright thing.

Into the jacket and helmet she went, into the capsule and shuttle at Canaveral. Her companion from the Army’s parallel program, Miss Able, was tall and dignified, no doubt as hardworking as Miss Baker herself.

She nodded at Miss Able, and at the crew—not mice this time, but provisions. Miss Baker’s crew consisted of vials of blood, samples of E. coli, of corn, of onions and of mustard seeds. Sea urchin eggs and sperm. Mushroom spores of the genus Neurospora, fruit fly pupae, and yeast. Who knew why those items had been chosen? Miss Baker did not, but she treated them respectfully. That was the mission.

She zipped her jacket with her own hands, and was closed into her capsule.

Two thirty in the morning. Cape Canaveral was dark. They jeered, her competitors, as Miss Baker rose, up, up, over the ocean and into the sky, but she didn’t care. They were earthbound, and she was a pioneer. Out the window, she could see fire and hoopla. Miss Baker was alive as she ejected from Earth’s gravity, alive as she returned to the sea. She was a star in a leather jacket, fetched from out of the Atlantic, healthy and grinning.

Flashbulbs and a press conference. What did the astronaut want? What could they bring her?

What is it like in space? they asked.

She asked for a banana.

Later that same day, she smiled for Life magazine, stretching her tail to its full length. Miss Baker posed with her medals and certificates, then went about her business as a private citizen.

She was married twice, first to a monkey named Big George, and then to another called Norman. She didn’t take their names, nor did she become a Mrs. For the second wedding, she wore a white lace train, which she tore off and waved at hundreds of spectators. If she was not wearing her flight uniform, she preferred to be naked.

She celebrated her birthdays with balloons and Jell-O, and she persisted in setting records.

To herself, and to her husbands, and to anyone who came near, she only said one word, in several languages: Astronaut.

It was their own fault if they didn’t understand.

* * *

In 1984, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the day Miss Baker slipped the bonds of gravity, the Navy gave her a rubber duck as a retirement gift.

When the reporters asked for an interview, she made no comment, but she thought about it.

For nine minutes in 1959, Miss Baker had been weightless. She’d pressed her fingers to the glass, and looked out into the glittering dark, a squirrel monkey in a capsule the size of a shoe box, floating in triumph three hundred miles above the world of men.

The Earth from afar was exactly the size of an astronaut’s heart. Miss Baker might eat it, or hold it, fling it into the sun or roll it gently across the dark.

She sat calmly in her flight suit and medals, holding her duck. She smiled for the cameras.

She asked for a banana, and it was delivered to her on a platter, as bright and sweet as victory, as golden as the sun.