Salutations, Tor.com! Welcome back to the Movie Rewatch of Great Nostalgia!

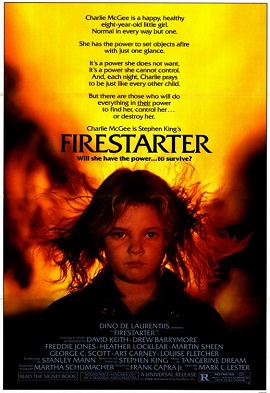

Today’s MRGN will be a little different from our usual fare, O my Peeps! Owing to Easter weekend madness and a truly absurd concatenation of scheduling conflicts, my sisters will not be joining us for this post; your Auntie Leigh will be flying solo on this one. And given that, I decided to do a film appropriate to my solo status: 1984’s Firestarter, adapted from the 1980 Stephen King novel. Yay!

Previous entries can be found here. Please note that as with all films covered on the Nostalgia Rewatch, this post will be rife with spoilers for the film.

And now, the post!

So! Firestarter is the story of young Charlene “Charlie” McGee and her father Andy McGee, who are on the run from what we hope is an entirely fictional secret branch of the U.S. government known as The Shop, who performed illegal experiments on Andy and his to-be wife Vicki, which gave them (faulty) psychic powers, which then got passed on to their daughter in distinctly non-faulty fashion, in a way which meant that the latent pyros on the stunt and special effects teams for this movie probably had the time of their lives.

As I mentioned in my Carrie post, I had really wanted to do Firestarter as the MRGN’s first Stephen King movie, but we switched to Carrie because my sisters had neither seen the Firestarter movie nor read the book it was based on, and were therefore not nostalgically equipped to comment upon it.

This obviously made perfect sense, but I was still a little sad about it. Because as I also mentioned in that post, Firestarter was not only the first Stephen King novel I ever read, but it was very possibly the first novel not aimed at a younger audience I ever read as well. It was certainly a great deal of the source of my childhood fascination with stories about psychic phenomena – a fascination King and I clearly share, given how many of his books center around the idea in one fashion or another. Firestarter, though, was arguably the quintessential Stephen King take on paranormal mental abilities and the probable results of their introduction to the modern world.

Needless to say, I adore the shit out of the novel, and have reread it probably at least a dozen times over the years. By contrast, I’m pretty sure that before this week I had only seen Firestarter the movie once or maybe twice, and that many years ago, but I remembered that I had loved Drew Barrymore in the role of Charlie McGee, and had general warm fuzzy feelings about the movie overall, and so I was moderately excited to see it again and see if it held up.

And, well. It, uh, didn’t.

We’ve all heard or read – or said – some variant on the truism that The Book Is Always Better Than The Movie, but I feel like that takes on an especially pointed truth when applied to movie adaptations of novels about psychic phenomena in general, and adaptations of Stephen King novels about psychic phenomena in particular. That latter may only be because King’s books were the ones that everyone tried the hardest to make into movies (because as I said before, Stephen King in the 80s was money, baby), but it was a distinct and recurring problem that I really should have remembered before getting my hopes up about Firestarter.

And it’s not like I’m not sympathetic to the inherent problem here. Figuring out how to visually depict things that are almost exclusively happening inside characters’ heads is really difficult, you guys. Many a film director has flung him-or-herself against that particularly sharp-edged windmill and come out the worst for it, and perhaps I should therefore cut Firestarter’s director Mark L. Lester a little slack about it.

Maybe I should, but I ain’t gonna, because I spent the whole film irritably making mental notes about the ways in which Charlie’s pyrokinesis and Andy’s “mental dominance” could have been depicted SO much less cheesily. So many directors seem to feel that there has to be some kind of obvious visual or aural component of an otherwise invisible action to make sure the audience knows something is happening, and I personally think this is bullshit. Mostly because it leads to eye-rolling nonsense like mandating that Charlie can’t set things on fire without being in her own personal and inexplicable wind tunnel:

Or that her father can’t mentally “push” people into doing what he wants without clutching his head and popping a forehead vein, which is supposed to convey the strain his gift is putting on him, but mostly just made David Keith look like he was trying (and failing) to take a massive dump.

Sorry, but no. Even Brian De Palma’s “quick zoom and violin screech” method of indicating psychic happenings in Carrie was less annoying than this. I am very much a fan of the “less is more” approach when it comes to conveying this kind of thing from the actors’ end, and just making sure that the results are the spectacular and/or visually communicative aspects of what’s going on. I feel that this is the key method in which to avoid much cheese when it comes to portraying ESP-type things on screen, and I also feel this is an area in which Firestarter very much fell down on.

Ham-handed visual cues were not the only failing of the movie, sadly. King’s novel was really about two things: the wonder and horror of a little girl with such destructive power at her beck and call was the main thing, of course, but it was also just as much about the terribly casual way it’s taken for granted that the U.S. government is doing illegal and awful things to its own citizens, with total impunity and horrific disregard for the principles it and we are supposed to be operating under.

The film adaptation of Firestarter sorrrrt of conveys that, but not with anything like the conviction (or power) of the novel. The best example of this, I think, is the scene with the postman.

In both the novel and the film, Andy McGee attempts to send letters to major newspapers and magazines to expose the fact that the U.S. government is hunting him and his daughter in completely illegal and unsanctioned ways, and in both novel and film, Shop agents intercept those letters before they can be delivered.

The difference is that in the film, the Shop’s resident hitman Rainbird just strangles the postman to death and steals the bag with the letters, whereas in the novel, the mailman lives. More importantly, the scene is from the postman’s POV, as Shop agents pull him over and hold him at gunpoint while they rifle through the mail for the letters, and then leave him behind, crying, because, he pleads, this is the U.S. mail. It’s supposed to be protected, because this is America, and yet, it isn’t.

It’s a scene that struck me vividly, even as a kid, because of how palpable King made the sense of utter betrayal the postman feels. The postman’s ideological anguish at the revelation that America is not the shining bastion of justice and good that we have always been taught it was is a theme that’s endemic to the entire novel, and while the government agents in the movie are obviously just as callous and awful as their novel counterparts, the movie’s failure to make that point as, er, pointedly as the novel did meant it just kind of melted into this nothing of random villainy. I know it’s maybe a bit weird that I’m arguing that it’s worse to make the guy cry than to actually kill him, but I’m talking about thematic and dramatic impact here. This is a story; those things matter.

Speaking of random villainy. There’s no denying that George C. Scott did a good job of portraying the deeply creepy semi-pedophiliac serial killer character of John Rainbird, to the point where I can’t decide whether the blatant whitewashing of what was supposed to be a Native American character might actually have been a good thing, because ain’t nobody going to want that in their ethnic group. And besides, statistically nearly all psychopathic serial killers are white men anyway. (Though of course the actual problem is that the whitewashing erased a chance for a Native American actor to have a significant role in a major Hollywood film, so.)

Also, holy crap is Martin Sheen young in this. Also jarring, because I totally forgot he was in this movie, and by far my most significant association with Sheen is in his decidedly heroic role as President Bartlet on The West Wing. But in fact, his cold and calculating Captain Hollister isn’t even the first “Stephen King evil government figure” Sheen had portrayed at that point, as he also played the apocalypse-bringing potential future President Greg Stillson in the 1983 adaptation of The Dead Zone. Which makes his later West Wing role kind of hilarious by contrast, doesn’t it.

This movie in general had a pretty stellar cast, actually. In particular I have to point out that Drew Barrymore’s performance as Charlie McGee is really way above and beyond what I would expect out of 95% of child actors that age. I know she rather went off the rails once she grew up (though by all accounts she actually pulled herself back on the rails as well), but in my opinion her fame as a child actor was entirely deserved.

Holy crap reaction #2: Hey, that’s Heather Locklear! Not that we got to see her for long, as she played the swiftly fridged wife/mom Vicki, whose character got even shorter shrift in the movie than she did in the book. (This is, probably, my one real beef with the novel.)

So, good cast, but the movie failed to use them very well. There were some good choices made in adapting the exposition from the novel, but the slow pace and weird editing choices killed nearly all the narrative tension that the book sustained so beautifully. The special effects were probably pretty good for the time (and it must have been hell, ha ha, to work with so much fire), but they were not employed to nearly their best effect, in my opinion.

I also have to note that the music for the movie was by Tangerine Dream, whose score for Legend, as you may recall, I considered so iconic and essential to the movie that I threw a temper tantrum at the director’s cut for taking it out. By contrast, well. I would not have stomped a single foot had someone decided to take away Firestarter’s “score”. I use the scare quotes advisedly, as one of the little bits of trivia I found about the film stated that Tangerine Dream never even saw the movie; they just sent a bunch of music to the director and told him to “pick out whatever he wanted”. Let’s just say, you can tell. Ugh.

Basically I would have made many many many different choices in how this movie was made, because as is, it doesn’t remotely do justice to the source material. I’m also pretty sure I would have been bored out of my mind had I watched this movie without knowing the source material.

In fact, I was pretty bored anyway. My sisters should feel pretty good about the bullet they dodged on this one.

So! In conclusion, O My Peeps, if you’re jonesing for some excellent psychic psychodrama avec a healthy side of evil government conspiracy, give the film version of Firestarter a distinct miss, and go read the book instead. You won’t be sorry, I promise.

And at the last, my patent pending Nostalgia Love to Reality Love 1-10 Scale of Awesomeness!

For Firestarter the movie:

Nostalgia: 6-ish

Reality: 3

For Firestarter the book:

Nostalgia: 10

Reality: well, I haven’t reread it all that recently but I’m willing to bet it’s probably at least a 9

And that’s the MRGN for today! Come back and see me reunited with my lovely siblings in two weeks! Later!

A lot of the reason why these 80s King movies were so cheesy is because most of them were filmed out of De Laurentiis’ studio in Wilmington NC, which was very much a B-movie studio. That is Orton Plantation on fire in the picture up there.

Not a lot to add, but I wanted to give my take on how directors can display mental phenomena on screen. Basically, I think The Force Awakens handled it near perfectly in the scene where Kylo interrogates Rey. No flashback-like images, no wavy screen effects – just intense facial acting between the two actors with some sound effects and scoring to represent what was going on.

Hmmm … Don’t think I ever saw the movie; even without personal experience, I knew that Stephen King adaptations had a … less than stellar track record. I remember the book fondly, though — it wasn’t my first King (that’d be The Dead Zone), but it might’ve been the first new King novel to come out after I’d started reading his stuff.

Maybe Charlie was just always carrying around one of those battery-powered personal mister/fans?

Somewhat related, but I’ve always hated how in the X-Men movies they had Professor Xavier put his fingers on the side of his head when he’s using telepathy (McAvoy in particular did this every time).

@@.-@ Surely just the half-squinty look that goes with the fingers to the temple would be indication enough.

@5 – Temple! Man, you don’t know how much it was bugging me to remember the word for that area of the head. I just had a total mind block for some reason. Ahh it feels good for that to be gone lol. Anyways, yes, the half squinty look is more than enough.

I’ve been considering a re-read of this. I re-read The Dead Zone recently and it was a very different experience from the film and my first time through it in my teens. Higher comprehension now I guess …

@6 A mind block, eh? If only there was a professor around who could help with that by tapping the side of his forehead :P

This would actually be a good movie to redo.

“the swiftly fridged wife/mom Vicki … This is, probably, my one real beef with the novel”

I don’t remember how this comes across in the movie (I think I’ve seen the movie twice for some reason, yet nothing from it ever sticks in my memory)… but in the book, although I would’ve liked to know more about Vicky, her death didn’t feel to me like as much of a gratuitous plot device as those things usually do. I think it’s because 1. Andy isn’t an action hero— he doesn’t go on a quest to take down the government for revenge— he’s just terrified and trying to protect his daughter, and he acts in anger maybe once (early on when he tells a Shop agent, “You’re blind”). And 2. the scene where he finds her body is genuinely disturbing in a way that doesn’t just serve to motivate the character. When the hero’s beloved is murdered in a superhero comic, the horror is that it happened to that particular person, but you already knew the supervillains were out there and that’s the kind of thing they might do. Here, it’s more like: if this can happen at all, to anyone, then something’s deeply wrong with the whole country (beyond all the things you already know are wrong).

Rusty @@@@@ 2:

That scene was very well done indeed. I remember being so impressed with how well they handled it. Not a wind tunnel in sight!

Robert @@@@@ 9:

Agreed. You think they’d let me direct it? :)

Eli Bishop @@@@@ 10:

You make a good point, and I had considered the thought that Vicki’s death might not count as fridging because, as you point out, it wasn’t the main motivator for Andy’s actions after – obviously his biggest motivation was to protect his daughter. But I left it in because even so, her character is a cipher whose only role in the story was to be a victim and die horribly, and that’s close enough to fridging for government work, ha ha.

I haven’t seen the movie or read the book, but it occurs to me that the Shop comes off as more powerful if they don’t kill the postman, because that means they don’t need to kill him. They are certain that he’s not going to be able to blow the lid on the conspiracy either.

I wonder what you folks think of Scanners, another movie from the same general time that has psychic powers shown on camera without the benefit of CGI. In my own opinion it is a film with less-skilled actors that stands up much better over time, but I might be biased. I don’t mind Firestarter, and I really appreciate some parts of it, but for me Scanners is the definitive psychic powers film of the 1980s.

I never got the wind tunnel effect either I thought it was lame. All telepaths grab there temples it’s like a rule or something in 90 percent of the movies I’ve seen. I remember Vicki’s death being less fridgy in the book but I read it like two years after I saw the movie so mid 80’s it’s been a long time. George C, Scott was epically creepy in this movie and other than the character’s name he didn’t scream native American to me nor did the books either. George works as nutso bad guy.

@@@@@ 13 Scanners is an interesting take on telepaths. I just remember lots of screaming and many dead Canadians. Did some of there heads explode?

Leigh, I gotta be honest, this movie would not have made my nostalgia list, mostly because I didn’t see it until I was a bit older, and could only appreciate its deficiencies. For me, the Dead Zone was the King novel/movie that had the most impact for me in my formative years (and also dealt with psychic phenomena), and I think that film holds up (slightly) better.

For good music connected with this movie, I strongly recommend “Daddy’s Little Girl” by Campbell award winner Julia Ecklar, from her album “Genesis.” There’s a fan video here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uGNNDFrQ3HI

“And besides, statistically nearly all psychopathic serial killers are white men anyway.”

I’m afraid that that’s something of a media created myth:

“Myth #2: All Serial Killers Are Caucasian.

Reality: Contrary to popular mythology, not all serial killers are white. Serial killers span all racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. The racial diversity of serial killers generally mirrors that of the overall U.S. population. There are well documented cases of African-American, Latino and Asian-American serialkillers. African-Americans comprise the largest racial minority group among serial killers, representing approximately 20 percent of the total. Significantly, however, only white, and normally male, serial killers such as Ted Bundy become popular culture icons.”

“Although they are not household names like their infamous white counterparts, examples of prolific racial minority serial killers are Coral Eugene Watts, a black man from Michigan, known as the “Sunday Morning Slasher,” who murdered at least seventeen women in Michigan and Texas; Anthony Edward Sowell, a black man known as the “Cleveland Strangler” who kidnapped, raped and murdered eleven women in Ohio; and Rafael Resendez-Ramirez, a Mexican national known as the “Railroad Killer,” who killed as many as fifteen men and women in Kentucky, Texas, and Illinois”.

Whoops. Forgot to provide the link:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/5-myths-about-serial-killers-and-why-they-persist-excerpt/

Suggest: John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness

Was gonna mention the serial killer myth, but trajan23 beat me to it. Nice catch.

For some reason, the media only reports on white serial killers.

Brian DePalma did the psychic thing great. Firestarter, less so. I mean, saying less is more is nice and all, but do you want someone just looking with no visual or aural indication of what;s happpening? That’s stupid, and sounds kind of boring.

This review was much better than another I saw today, where the reviewer categorizes Rainbird as a “child molester”, but why even go there? He wanted to look into her eyes as she crossed over into death, so yeah.. he’s a nut, but I wouldn’t say he likes little kids for sexual reasons. I don’t understand that connection. Not in the book or the movie. The character kills indiscriminately (& usually for a paycheck), so I don’t understand. What am I missing?