“Science fiction is great,” the French artist Jean Giraud—better known as Moebius—wrote in a reflection on The Airtight Garage, the comic from the late 1970s often considered his masterwork, “because it literally opens the doors of time and space.” He might as well have been talking about the revelatory feeling of viewing his art. It certainly sums up my feelings upon first reading his masterpiece, Edena.

In a 1996 lecture to Mexican art students, Moebius drew connections between illustration and all the other arts. “There must be a visual rhythm created by the placement of your text,” Moebius informed the students. “The rhythm of your plot should be reflected in your visual cadence and the way you compress or expand time. Like a filmmaker, you must be very careful in how you cast your characters and in how you direct them.” He then compared drawing to composing music. Finally, towards the end, he provided a simple but profound insight into reading not only his own work, but that of comics and visual mediums as a whole: “Colour,” he said, “is a language.”

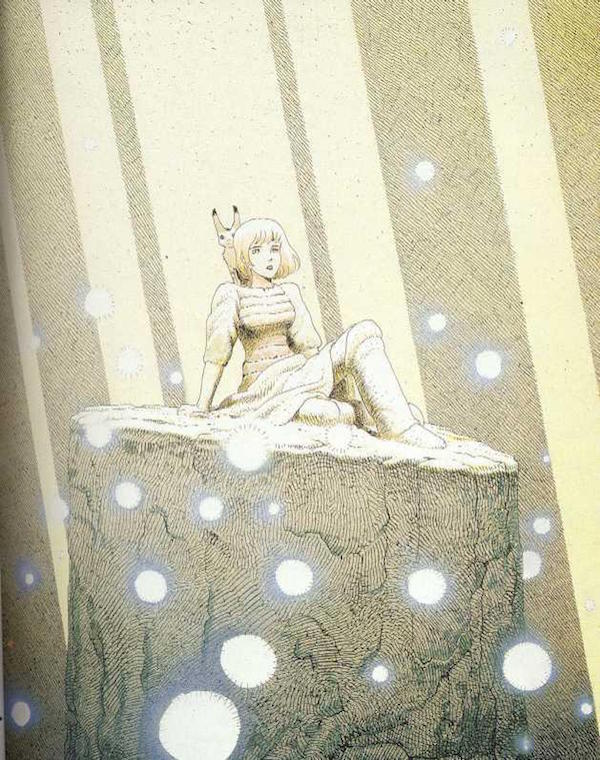

It was a language Moebius would become fluent in. He was born in May, 1938—a month before the first issue of Superman—and, within a few decades, he became one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. He first began calling himself Moebius in the 1960s while drawing strips influenced by Mad Magazine; the pseudonym, a riff on the mathematical concept of the Möbius strip, stuck a decade later, becoming better-known than his birth name. Moebius’ work is so rich because of how much it draws from the other arts: his compositions read like music, his colours like lyrical language. His art was at once alien and human, echoing everything from the Art Nouveau of Mucha to the wordless novels of Lynd Ward to the sci-fi of his contemporaries, yet seemed a revelation, a revolution. In 1977, he created Arzach, a wordless comic featuring the adventures of a warrior on a white winged creature; later, he compared the enigmatic quality of the piece to the inscrutable monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Arzach’s silhouette on his white pterosaur resembles that of Nausicaä—the protagonist of Hayao Miyazaki’s 1984 film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind—on her signature glider. This was no coincidence; Miyazaki himself revealed in an interview that he “directed Nausicaä under Moebius’ influence,” and, in 2004, both artists drew artwork honouring the other: Miyazaki a soft image of Arzach, Moebius a haunting fey illustration of the Valley of the Wind’s princess.

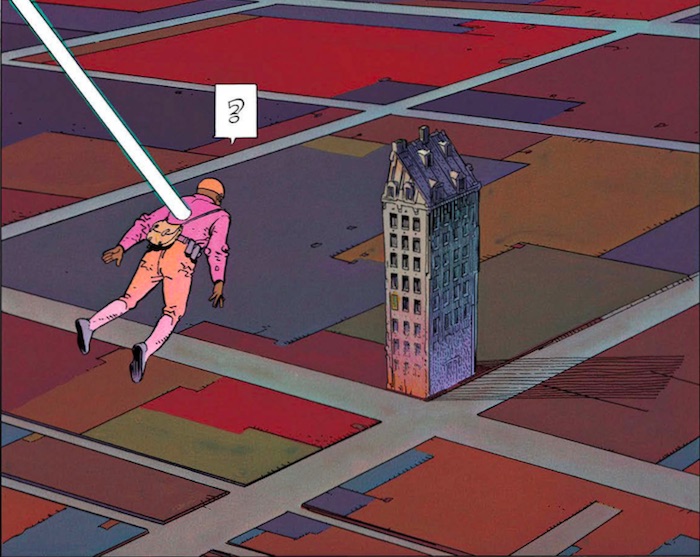

Moebius went so far as to name his daughter Nausicaä, a tribute to their friendship and mutual influence. With Alejandro Jodorowsky as writer and Moebius as artist, he created in The Incal a vast, circular narrative that seemed groundbreaking for its time. What made Moebius’ work grand was the same thing that animates great fantasy and sci-fi: that the beauty and terror of a world that does not as yet exist, or may never, can make the real world more beautiful and terrible, that the rich eldritch colours and contours of a far-flung fantastic realm make our own reality’s colours richer. A mirror from the future, or a shimmering glass from Faerie, sometimes shows the real present just as well, or, ironically, better than the ones we may look into now.

Despite his fame in France and with renowned directors like Miyazaki, however, Moebius still, arguably, remains too-little-known in America. “You see it everywhere,” Ridley Scott said in 2010 of the French artist’s influence, adding that “it runs through so much you can’t get away from it,” but this is precisely where Moebius unfortunately lies for all too many people: beneath the surface. This is partly cultural; in France and Belgium, comics, or bandes dessinées (literally, drawn strips), tend to be held to a much higher esteem, even being classified as “the ninth art” alongside cinema, photography, and many others, and the Western stigma that labels cartoons as a form for children holds less true in Japan. Moebius’ relative obscurity in America is partly because comics, themselves, have only recently begun to attract the wider critical attention they deserve. And this is truer, still, of one of his most underrated, yet most ambitious, solo works: the lush, extraordinary cycle of stories, The Gardens of Edena, which freely blends fantasy and sci-fi, and which was released as a whole in a gorgeous new edition last December. Reading the stories for me was a revelation: here was a luxuriant grand narrative that, like an operatic Midsummer Night’s Dream on the starry deck of a spaceship, asked where the nebulous road of dreams ends and the road of non-dreams begins, all while telling a byzantine tale of love, politics, the body, and evil. To me, Moebius’ Edena cycle may well be his masterpiece—and one I find even more interesting due to its intriguing explorations of gender.

Moebius began the series as, of all things, a car advertisement. Citroën, a French car manufacturer, had asked him to draw a comic advertising their vehicles in 1983. Initially, he wanted to decline, then rethought it. “Citroën,” he wrote in story notes for the comic that would begin Edena, “was not like other car makers. They are a little like the poets of popular automobiles.” He decided to create a “mythical car” to reflect the manufacturer, and, as he sat down to draw, the story suddenly flooded into him. In half an hour, he drew forty pages of layouts, “almost in a creative trance.” Such fluid inspiration was rare for him; Edena, from the very start, was something special.

Moebius named the story “Upon a Star,” and it introduced the saga’s protagonists, two interplanetary mechanics named Stel and Atan. He forced himself, in his own words, “to draw ‘Upon a Star’ in a style as pure and simple as possible”; the panels used the ligne claire style famously championed by the Belgian artist Hergé in his Tintin series, which involves straight, strong lining with no hatching, and which often features cartoonish figures set against realistic, highly rendered backgrounds. (This, along with Moebius’ soft but salient application of shadows, gives many of his images, in Edena and elsewhere, a solarised, flat-yet-full feel.) Citroën so loved the comic that they released it as a limited-edition book—now a rare collectors’ item—and Moebius began work on the full story, guided by the lantern of that vision he had had when he first began to outline the cycle, yet very uncertain, as he later wrote, of how the story would evolve.

In this vision of the future, humans use “molecular synthesizers” to digitally create food. They routinely have organ transplants to extend their lifespan and take “hormonode,” a drug that prevents the creation of any sexual features, including body hair; the very idea that someone could be distinctly male or female in any sense is considered “primitive” or even “blasphemy.” Humans are, as Atan says, “ageless, sexless, shapeless.” In the first few chapters, Stel and Atan have a loving, if sexless—literally, in two senses—relationship, a kind of sweet platonic partnership. From the earliest panels, Atan’s features are slightly more feminine than Stel’s, but both, like all humans seem to, go by “he” and “sir” as (ironically patriarchal) gender-neutral pronouns. However, when the two crash-land on Edena—a lush landscape echoing the similarly named biblical garden—they are forced to begin eating food from nature and stop taking hormonode, which they no longer have a supply of. If the universe outside of Edena that Stel and Atan come from represents science, the fey landscape of Edena is closer to fantasy; it is populated by fairies and other mythic beings, all brimming with a quiet magic, a world more akin to what J. R. R. Tolkien simply called “Faerie” in his landmark 1947 essay on the fairy-story as a form.

After a while, it becomes clear that Stel and Atan’s features are changing: Stel becomes distinctly masculine, while Atan—soon to be renamed Atana—has grown prominent breasts and an hourglass curve. They have become gender archetypes, the Adam and Eve of a new world—and when Stel, suddenly filled with a lust he has never before felt, tries to make a move on Atana, she hits him and flees. (As with the religious version, knowledge of their newfound bodies leads to a kind of metaphorical expulsion and pain—and, fittingly, this all starts by Stel and Atan eating apples.) The story then transforms into a dreamlike quest paralleling their stories, as they slowly come to understand their identities, and realise that they love each other—but their changed bodies, Atana’s in particular, cause them to be treated as dangerous abominations to the other humans they soon come across in Edena, and, in particular, a threat to a strange malevolent being that begins to invade their dreams, who becomes the cycle’s primary antagonist. This prominence of the body was intentional. Moebius wrote that he wanted to show what happens when one switches from “artificial to natural food,” which partly reflects his influence by Guy-Claude Burger, whose “instincto therapy” diet of instinct-based raw food—primarily fruits, like in Edena—Moebius was experimenting with. But it goes beyond this. In Edena, sex and gender become anarchic, powerful, dangerous—a combination that resonated with me as a trans reader.

Stel and Atana learn that their identities have layers. Atan was always Atana, her true self suppressed by the homogenising drug hormonode, and the same is true of Stel. (The order of events is ironic; hormone therapy, which already sounds a little like “hormonode,” often helps bring out the features of our gender.) To be sure, the characters are not technically trans, as their newfound bodies correspond to their gender identities; ironically, it’s as if they transition into being cisgender. Yet their confused memories of their previous gender-neutrality and greater sense of joy in their new bodies adds a subtle queer context I loved. I hadn’t expected these explorations of gender by Moebius, and when I realised what was happening, I smiled.

I suddenly couldn’t stop reading. I forgot I was on my bed, a book sprawled open before me; I was in Edena’s dreamscape. When I looked at my phone again, hours had disappeared and midnight had arrived, soft as shinigami footsteps, and for a moment I felt disoriented, like a scuba diver returning from the drone of their breaths to the chaotic noise of the surface. While Atana was not trans in the sense I was, her story had captured me, all the same: the power and perils she had gained as a result of her gender, the delightful subversiveness of being gender-non-conforming in a world where everyone was expected to be the opposite. It was a queer tale—but stealthily. It seemed so familiar, on some level, this way that your true identity is always there, but hidden away in the night of the self, buried under the yellowing grass, the ornate mausoleums, of a life lived for so long in denial. Once we stop holding back who we are, we can begin to bloom. I wanted to finish the book instead of teaching the next day. But I also didn’t want to get to the end, in the strange way we sometimes love a book so much that we feel slightly afraid to finish it.

Edena has its uneven moments. Stel and Atana often seem to embody gender stereotypes, for instance. However, this may be intentional. Their gendered behavior is extreme when they first realise that their bodies have changed; when you first begin to transition, you may likewise go wild, presenting more femme or masculine than you might later decide to, simply because it all feels so wonderful and new to finally be able to walk through the world like that. And it’s difficult to feel that Stel and Atana are solely stereotypes the longer we venture through Edena with them, as the world around them is so lush and diverse that they begin to seem distinctive just by proxy. At parts of the narrative, Atana indeed becomes a prototypical damsel in distress, captured by a villain and pursued by the heroic Stel, yet Atana is also frequently depicted as a tough, fearsome woman in her own right. Moebius invests these archetypal figures with something unique, with a psychology at once real and fantastical. Unlike Moebius’ episodic, postmodern The Airtight Garage or his more frenetic collaborations with Jodorowsky—The Incal and Madwoman of the Sacred Heart—Edena generally moves at a gentle pace, allowing his enchanting, and, at times unnerving, world to unfold.

Edena is an overshadowed masterpiece, a surreal, timeless tale. If colour is indeed a language, this is one of its lovely, too-long-forgotten poems.

Gabrielle Bellot is a staff writer for Literary Hub. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New York Times, Tin House, Guernica, Slate, New York Magazine’s The Cut, Electric Literature, HuffPost, and elsewhere. Find her at gabriellebellot.com.