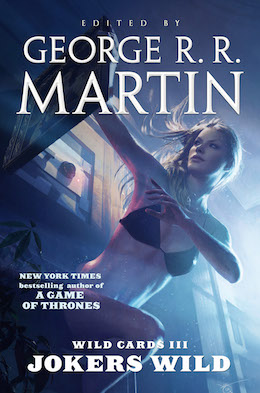

Jokers Wild, the third volume in the Wild Cards series, covers a single day in New York City: September 15, better known as Wild Card Day. Like last month’s Memorial Day holiday in the U.S., Wild Cards Day began as one of remembrance. While Memorial Day initially arose as a patriotic Day of the Dead of sorts, when people decorated the graves of those who had died in the Civil War and later conflicts, on September 15 the Wild Cards world remembers those who gave their lives in an attempt to stop the attack, those who died in the streets, those rewritten by the virus, and those forever changed. As we see in Jokers Wild, however, the holiday is more than that. It is also a celebration of the many subcultures created by Dr. Tod’s attack, and the communities that developed in its wake. Nats might attend the parades, but foremost the day is about jokers, aces, and the victims of the black queen. The parades, parties, and memorials are put on by jokers and aces, with nats left to the sidelines. It is fitting, then, that the same can be said of the artistic representations described in the book.

In Jokers Wild, the authors include something of a meditation on images and artistic portrayals throughout the book. They provide us with a survey of four different sculptural and visual representations which exhibit wild card symbolism and meaning-making.

First, we see illustrations of our beloved friends in the Jokertown parade floats, adding to the revelry and excitement in “deep Jokertown.” Parade floats have a long history in the U.S., appearing in everything from local celebrations, political showcases (first float included in a U.S. inauguration: 1841), and revolutionary demonstrations (suffragette marches). Their modern incarnation can be traced to the urban parades of the late 19th and early 20th century, when workers, merchants, and “display artists” constructed floats tied to industry and business. Still, floats can be distinctly local and intensely personal, allowing small groups and communities to express pride, memorialize the past, tell their stories, and create their identity. We see something similar in the Wild Card Day festivities in Jokertown.

Throughout the book, the main POV characters observe these three-dimensional collages in action, either pulled up in preparation for the big day or clogging the streets during the parade. Demise sees “a crepe float of the Turtle.” Fortunato spots other crafted images: “Des, the elephant-faced joker, done up in chicken wire and flowers. There was Dr. Tod’s blimp and Jetboy’s plane behind it, complete with floral speed lines. A clear plastic balloon of Chrysalis floated overhead.”

The Jokertown floats seem to be do-it-yourself creations. Most represent prominent people who have impacted the lives of nearby residents. They have local significance in Jokertown, with Chrysalis and Des being eminent community leaders. The historical theme so common in holiday pageants today is represented by the embodiments of Dr. Tod and Jetboy, the blimp and plane. As to be expected in such a raucously democratic display, we also find pranks and rebellion, most notably in the irreverent float sporting a gigantic double-headed phallus (eventually demolished by the cops). These floats are images of jokers, by jokers.

Just a few pages later, these homemade, exuberant images are juxtaposed with the ice sculptures by creator Kelvin Frost, the art critics’ favorite who dubs his work “ephemeral art.” Commissioned by Hiram for the aces-only party in the restaurant Aces High, they too serve as portraits of important individuals in the history of the wild card virus. In contrast to the kitschy paper crepe floats, many of Frost’s ice sculptures reference distinguished artworks from the past: “Dr. Tachyon pondered like Rodin’s The Thinker, but instead of a rock, he sat upon an icy globe…There were the Four Aces at some Last Supper, Golden Boy looking much like Judas.” The artist even managed to represent Croyd, “a figure with a hundred blurred faces who seemed to be deep in sleep.” Hiram marvels at the expressiveness embodied in the images and their ability to evoke emotions in viewers: “Jetboy stood there, looking up into the sky, every inch the doomed hero and yet somehow the lost boy, too.”

When Jay Ackroyd remarks that the sculptures will sadly melt, Hiram explains, “the artist doesn’t think so. Frost maintains that all art is ephemeral, that ultimately it will all be gone, Picasso and Rembrandt and Van Gogh, the Sistine Chapel and the Mona Lisa, whatever you care to name, in the end it will be gone to dust. Ice art is therefore more honest, because it celebrates its transitory nature instead of denying it.”

We, of course, can say the exact same thing about the Jokertown floats, assemblages of wire, paper, and plastic, soon to be dismantled from their truck beds. In fact, the ephemeral and transitory quality of the floats becomes explicit at end of the day (and book), when the (real) Turtle carries aloft the float of Jetboy’s plane, its shape disintegrating and trailing crepe flowers through the air behind it. One wonders if Frost would recognize the parallel.

The ice artist, an ace, depicts aces, and obviously considers his fellows to be worthy subjects for the greatest artworks in western history. There are no jokers here, no Des or Chrysalis. At the aces-only party, it seems the subject matter remains aces-only as well. The aversion to joker ugliness felt by Frost’s patron, Hiram, finds itself reflected in the iconography of the sculpture. Despite Frost’s pretensions, we find here a reminder that his artwork is truly shaped by the man who pays the bills.

The commercial aspect of wild card art comes into play again when Wraith finds another series of representations in the Famous Bowery Wild Card Dime Museum, available to the paying public for a $2 admission ticket. Rather than the temporary sculptures of the parade and party, in this case we find a permanent and curated installation, although closed for the holiday and patrolled by a museum guard. Its dioramas show wild card history, both worldwide (Earth vs. the Swarm) and local (the Great Jokertown Riot of 1976). Portraits are located in the Hall of Fame, and it is there that we see the kitschy wax statues of Jetboy, the Four Aces, Tachyon, Peregrine, Cyclone, Hiram, and Chrysalis. The art of the Dime Museum is different than that of the parades and the highbrow creations of Frost. In this case, the images are sensational, melodramatic, and designed to draw in customers.

The Bowery Museum is modelled on historical dime museums, such as the real life American Museum created by P.T. Barnum and destroyed in a fire in 1868. Like its predecessor, the Bowery Museum is a bastion of popular culture, its visual likenesses augmented with real life artifacts donated by various figures (like Tachyon and the Turtle) or collected from historical events. Real life dime museums also included “freak shows” that put disabilities on display. The Bowery version flaunts a sobering reality of post-virus life, embodied in the corpses of 30 twisted babies, embalmed in glass jars. The display, oh-so-sensitively entitled “Monstrous Joker Babies,” turns the bodies of dead children into objets d’art. These are portraits of the silenced, the secret, the taboo…the thing that nobody likes to talk about.

Later in the book, Wraith encounters the fourth major example of wild card imagery, the religious iconography sculpted on the doors of Our Lady of Perpetual Misery, Church of Jesus Christ, Joker. Into a visual program heavy with symbolism, the authors channel the theology of A Canticle for Leibowitz, describing the crucified Jesus thusly:

He had an extra set of shriveled arms sprouting from his rib cage and an extra head on his shoulders. Both heads had aesthetically lean features. One was bearded and masculine, the other was smooth cheeked and feminine…The Christ was not crucified upon a cross, but rather upon a twisting helix, a convoluted ladder, or, Jennifer realized, a representation of DNA.

Rather than the prominence given to suffering in traditional depictions of the crucifixion, this new Catholic devotional art emphasizes holy mutation. DNA becomes fundamental to the sacred cosmos and the godly figures that populate it.

Other people portrayed in the illustrations of wild card theology include a double-faced Tachyon. One side of his face was angelic, while:

the other was the leering face of a demon, bestial and angry, dripping saliva from an open mouth ringed with sharp teeth. The Tachyon figure held an unburning sun in his right hand, the side of the angel face. In the left he held jagged lightening.

Note the iconographic detail, that the right and left (sinister in Latin) hands are the “auspicious” and “inauspicious” sides, a symbolism in Western religious art that pre-dates the Romans. Here Tachyon becomes a god and devil both, responsible for bringing evils into the world, but also (depending on your interpretation) a chance for salvation.

Perhaps my favorite piece in this religious cycle is the fresh take on the “Madonna and Child,” a motif in Catholic art that has artistic origins as far back as Egyptian depictions of Isis with Horus. Here the artist shows us:

…a smiling Madonna with feathered wings nursed one head of a baby Christ figure at each breast, a goat-legged man wearing a white laboratory coat carried what looked a microscope while cavorting in a dance, a man with golden skin and look of perpetual shame and sorrow on his handsome features juggled an arching shower of silver coins.

The two-headed Christ child nurses from an angelic Madonna, but rather than the wings of an angel, I wonder if we instead see a representation of Peregrine, that feathered feminine icon (who in future books will become the mother par excellence of an ace with god-like powers). The man with silver coins is Goldenboy, but I’m not exactly sure about the goat-legged man. I think he could be interpreted as several different characters. Who do you think he represents?

While the creators of the sculptures aren’t always made clear, all the imagery is closely associated with those changed by the Takisian virus. What is significant here is that this art was not created by nats. Real life scholars might dub an analysis of these images a “people’s art history” or “art history from the bottom up.”—in other words, rather than focusing on art from the dominant class (or perhaps the dominant DNA?), these images derive from subcultures, from society’s margins. This art was born within wild card culture, and it expresses the voices of jokers and aces. The artists narrate their own histories and myths, deciding for themselves which individuals are meaningful and worth depicting. Especially interesting is the fact that the images do not portray a unified, cohesive picture of the world, but rather a fractured, disparate worldview representing both joker and ace interpretations. I suspect nat scholars would not call this a “people’s art history,” but rather something like a “social history of wild card art”? Or perhaps an “art history of mutation”? I imagine the nat art historians of the 1950s would casually mark its outsider status by labeling it a “history of non-natural art’” (as with today’s delineation between “Western” and “non-Western” art). Opinions welcome, though—what do you think nat scholars would call it?

Regardless of how we label the study of art in Jokers Wild, the four main examples of visual culture described in the book represent a fascinating variety of materials, styles, functions, and creators. The authors gave us a wonderful look at art that expresses the multiplicity of voices in joker and ace communities, and chronicling these voices for us nat readers becomes especially significant given the book’s single-day timeline, as another means of marking the fortieth anniversary of the wild card and driving home the world-changing impact of that date.

Katie Rask is an assistant professor of archaeology and classics at Duquesne University. She’s excavated in Greece and Italy for over 15 years.