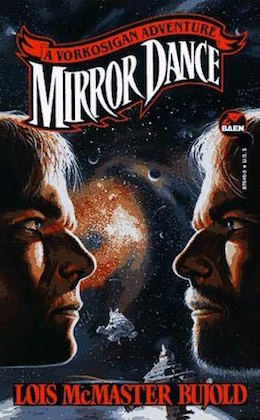

We’re still wading slowly into the shark-infested waters of the Doppelgangening. As of the end of chapter four, no one has been killed. Things are getting darker, though, because chapters three and four explore Mark’s childhood. Miles’s childhood involved a lot of fractures and medical procedures, a school that taught him to recite entire plays, and ponies. Mark’s did not.

This reread has an index, which you can consult if you feel like exploring previous books and chapters. Spoilers are welcome in the comments if they are relevant to the discussion at hand. Comments that question the value and dignity of individuals, or that deny anyone’s right to exist, are emphatically NOT welcome. Please take note.

If you can use a uterine replicator to replace a woman for gestational purposes, it makes sense that you could then have a number of children who are functionally motherless. They can lead lives completely separate from any woman who has a biological connection to them from the earliest stages of fetal development. And in most cases also from any man who has a biological connection to them. (Athos is a major exception here—I’m not allowed to live there, but I like Athosian attitudes towards parenting. Dear Athos, Go You! Please get over your thing about women. Thx, Me.) Like Terrence Cee, children can have so many genetic contributors that it is impossible to identify two biological parents.

This world of amazing potential is great for everyone but kids. In fairness, the story of the kid who might have had a terrible genetic illness but didn’t, because doctors patched up his genome with some spare donor genes around the time he was conceived, is not the stuff that space opera is made of. Nicolai Vorsoisson’s story might come the closest, and that part of it is fairly pedestrian—far less dramatic than his father’s murder and his mother’s role in saving the universe. Uterine replicators offer great options for parents looking to facilitate prenatal medical treatment, or address maternal risks associated with pregnancy, and that is their most common use. They also make it possible to create children who are completely alone in the universe. They are the very most orphaned of orphans. I wrote my thesis on orphans, so I have a lot to say about this.

Now, today, in the world we live in, children who are separated from their families and communities are incredibly vulnerable. They are easy targets for human trafficking—sources of sex and labor that no one cares about. Not only do most of the institutions that care for these children fail to do anything about this, some of them are trafficking children themselves—worldwide, over 80% of children in institutional care have family members who would care for them. But wealthy people feel good about giving large donations to orphanages, and they don’t feel good about giving handouts to needy families. So unscrupulous people build orphanages, and then use money or promises of education and medical care to persuade families to place children in them. Institutions collect money from donors and “voluntourists” and the kids get to be in a lot of selfies with people who think they’re doing some good in the world. Education is limited, supervision is poor, resources are scarce. Eventually, children get too old to be appealing to donors and visitors anymore. Then they get a job, or they leave the orphanage one day and don’t come back. They go further and further away from their families, becoming more vulnerable every step of the way. Separating children from families is dangerous.

When Bujold writes about children, these dangers are clearly on her mind. We saw this with the Quaddies. When someone cared about the Quaddies, being owned by a corporation and only able to live on a corporate-maintained habitat was OK. Mostly. The entertainment options were stultifyingly boring and the psychological manipulation was intense, but most human rights issues were mostly dealt with in accordance with reasonable standards of human decency. When those caring individuals were replaced by others who were more concerned with the corporate bottom line, suddenly the Quaddies were all post-abortion experimental tissue cultures instead of people. The only reason to create children without parents is to make sure that no one stands in the way when you want to exploit them. They have no families and no communities to protect them. Their entire lives can be controlled for other people’s purposes. That’s Mark.

So what’s up with Mark? He was raised until age fourteen in a House Bharaputra facility with clones intended for brain transplants. He was tortured medically so that he would be a physical match for Miles. He excelled at his programmed learning courses. At age fourteen, he was delivered to the Komarran resistance and to Ser Galen’s control. Galen abused him physically, emotionally, and sexually. Mark came to hate Miles, probably because hating Galen wasn’t particularly helpful. He had no experience of making decisions and only illicit opportunities to act independently.

The things that we see orphans as lacking are the things at the core of our beliefs about what families should provide. We want to believe that families make children safe and give them sources of strength. The intelligence gathering that provided the information about Mark’s like with Ser Galen was ordered by Lady Cordelia, who, like Miles, sees Mark as a family member who is worthy of protection. This is why Miles gave Mark the credit chit. Last week, I speculated that he spent it on drugs and ID. This week, we learn he spent a lot of it on the map of House Bharaputra that he’s using to plan Green Squad’s raid. Mark’s plan is incredibly misguided; He has no way of convincing House Bharaputra’s clones to believe him instead of the lies they’ve been told their whole lives. He can get to their dormitories, and he can get in, but he can’t get the clones to board the Ariel. He just wants to, because he’s twenty and he wants to save some lives and take down House Bharaputra. It’s too bad that this plan is doomed, because it’s really touching.

Join me next week, when Mark reaches Jackson’s Whole!

Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer teaches history and reads a lot.