The season of ghouls and goblins upon us, and the monsters that show up often reflect our fear of the unknown. Across the street, my neighbors drape orange lights around tattered black clothes that stream from ghoulish skeletal masks. Pumpkins appear carved to reflect a kind of hunger that speaks to nature: We will all be devoured by the plants. The monsters in our culture that are most common, I think, involve ideas like “undeath” (which sounds like it isn’t such a bad deal if you can stomach a little murder) and afterlife entities like ghosts. Frankenstein’s monster and his bride are reconstituted dead bodies. Many of our modern monsters and monstrous frights involve the unknown, and for us, that means death.

But in other eras and other times, the unknown meant something more than just death. The unknown began a few miles from home, at the edge of the villages where the forests became dark, or the sea might drop off into an abyss at the edge of the world. On the maps of the world, scholars and learned men drew pictures of sea dragons and wrote Here there be Monsters. Stories and myths and legends filled the night with tales of the distant journeys and the bones of dinosaurs emerged occasionally to warn of dragons. The horrors of the world were close, and the unknown surrounded everything beyond them. There are monsters that used to be as common as vampires and mummies, but they have faded as maps have gotten smaller and the idea of the unknown has shifted out of the physical world, into a metaphysical one.

Skiapodes

Described by Pliny the Elder as having only one leg and spending much of their life lying on their backs in the sun, these monstrous men used their giant, singular foot to grant them shade. They have been called Monopods, and despite their singular appendage, they are described as speedy. They appear throughout medieval marginalia and art as a monstrous creature, a race of human so alien that when they appeared in C.S. Lewis’ Voyage of the Dawn Treader as “Dufflepuds” they were described not as men, but as dwarves. Perhaps the greatest appearance of a monopod in modern literature, though, is in Catherynne Valente’s seminal duology The Orphan’s Tales, where a monopod makes a memorable appearance In the Cities of Coin and Spice among numerous other monstrous and fabulous creatures ripped from medieval bestiaries.

Giants

Tales of giants abound in medieval literature. One foundational text of Arthuriana describes King Arthur’s adventure defeating the Giant of St Michel’s Mount who threatened to split the Duchess of Brittany in twain via his monstrous ardor. Giants are littered across England. Sometimes, their face is on their chest, and they are called “Blemmyes” and were rumored to live in the far corners of the (flat, obviously, ergo capable of having “corners”) world. Medieval scholars often relied on the tales of the Nephilim in the Bible to explain the presence of giants, and their wickedness. Yet, stories of giants precede Christianity, and we simply do not know how long the forest primeval was haunted by the nightmare of giants devouring children, raping women, and towering over trees. When A Song of Ice and Fire’s Wunwun falls in battle, he fights for the king of the north, but the origin of his genre trope is one of terror and death at the hand of kings.

Bisclavret

A specific man in a specific story—but a story and author I, personally, adore—creates one of the earliest known references to werewolves in literature. Marie de France, a 12th century Anglo-Norman noblewoman, wrote short stories as allegorically-veiled gossip, pulling on Ovid, Arthuriana, folklore, and the like, to describe circumstances both fabulous and frightening. In one of these tales, Bisclavret, a nobleman goes to the forest, hides his clothes, and becomes a wolf. Most interesting, to me, is how society treats him. Naked, he is a dog and no one even recognizes him. Clothed, he is a man of power and authority, and no one questions him or attempts to cure or stop the wolf inside the man. It is, at once, a fascinating portrayal of nobility and power in 12th century Normandy, and a way of thinking about the monstrous nature of those in power. The complexity inside the simplicity of this little lais haunts my thoughts about justice and power. The monstrous element, the unknown inside the man that ruled there, was a force of nature that all accepted, in the same way they accepted him as ruler in full once he was wearing clothes again. (And, don’t get me started on the biting off of noses!) I was thinking much on the manner of transformation of Bisclavret when I wrote my own form of werewolf, in the Dogsland trilogy, though it does not seem adequate to explain the calories required to transform the body. Modern creators embrace a monstrous, high-calorie transformation, and unwittingly explain the devil’s appetite through this painful, physical growth. The gruesome transformations of physical form presented in what is probably the classic modern werewolf archetype, in An American Werewolf in London, seem to have shifted the monstrous myths and added elements of biological reality that can explain the rapacious feeding quality: after burning so many calories to transform, the body must be famished and burning itself alive to keep the transformations moving.

Bestiary Beasts

Real creatures that exist in the world have been painted and portrayed in such odd fashions, described as such monsters. Dolphins were no stranger to sailors of Europe, but their appearance in marginalia and the stone carvings of Rome often portrayed them with a fabulousness that is reminiscent of dragons, not biologies. Across the margins of texts, men and birds and beasts tumble inscrutably like fever dreams, perhaps explicating complicated theological virtues, perhaps not. But, again, like the dolphins that were carved in stone in ancient Rome and did not change their form in art for centuries, real beasts were mere myths a few miles away from sea, while the old art passed around from community to community as property changed hands. Artists modeled their art upon the art that they saw. Like a game of monstrous telephone, a hideous caricature of a dolphin moved from one artist to another who had never seen the original creature. Crocodiles, hippopotamuses, and all sorts of birds and cultures received the same treatment transforming the world that existed into a dream of nightmares and gruesome, demonic fears.

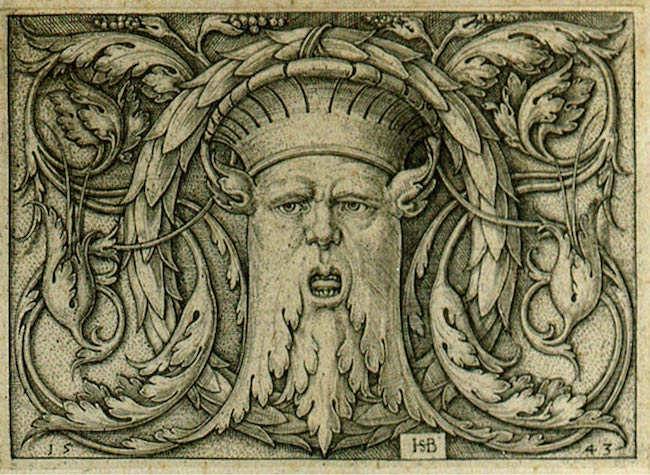

The Green Man

In the classic French courtly romance, Silence, a cross-dressing woman becomes a powerful knight, defeats a dragon, and more. But, beyond this exciting tale of a woman knight, there is a late appearance as a sort of deus ex machina, of a madman in the woods who is dangerous and wild and must be tamed. Of course, he is Merlin, the magician. But, he is playing a part that ties into an old myth of an old monstrous creature of the unknown. The Green Man, or The Wild Man, or whatever you want to call him, is a mythical and mystical creature that may be seen as a venerated forest god. His appearance as the last of a magical race in the character Someshta and death in Robert Jordan’s “Wheel of Time” is a harbinger of doom and darkness as the forests will suffer Blight in the times to come. But, his origin is likely one of death and destruction and terror. The Wild Man, the uncivilized man, the Green Man of the Woods, was a force of nature, like death itself, where bodies merged with the wilderness. It is a liminal man, then, and death-like in its portents: Where men live wild, they are dangerous and a threat to all that is civilized. When bodies fell, the green spread over their cheeks, and the roots of trees merged and devoured down to the bones. Merlin is brought back from this wild state with the trappings and temptations of civilization. He is given a fine meal, wine to drink, and clothes. Like Bisclavret, he is almost immediately returned from a state of madness to a state of authority and importance.

As the unknown dissipated to the adventures of scientists and soldiers, the maps shifted away from monstrous imaginings to depictions of wonders natural and named. Where once there were monsters, a dot marks a kingdom of men with a word and a name. Where once the forest edges loomed dark and fearsome and the unknown was ever close, communities grew up, filled in, and found ways to build roads, build connections, and march soldiers town to town. The monstrous unknown that remains to us is all around us: nightmares of metaphysical monsters, an eternity of deathless stasis, alien races, death, the refashioning of flesh in horrifying ways, and superheroes appearing at my doorstep. Superheroes are monstrous, if anything is. They are separated from the society they presumably protect, and exist in that liminal, unknown space where knights and monsters used to fight and spin around such that sometimes monsters were knights and knights were monsters. We hand candy to the unknown until the twilight falls into darkness and the moon rises. We teach our children where the edges can be trespassed and dreams can root, and like our fathers and mothers before us, encourage them to step out bravely with us into this twilight.

Joe M. McDermott is best known for the novels Last Dragon, Never Knew Another, and Maze. His work has appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His latest novel, The Fortress at the End of Time, is available from Tor.com Publishing. He holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Program. He lives in Texas.

Joe M. McDermott is best known for the novels Last Dragon, Never Knew Another, and Maze. His work has appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His latest novel, The Fortress at the End of Time, is available from Tor.com Publishing. He holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Program. He lives in Texas.