In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Science fiction is a broad category of literature: you can have stories set in the far future, the present day, or the distant past (and even mix these together in a time travel tale). You can set your story right here on Earth, on a distant planet, or some more exotic place. Or you can create a world to your own specifications. Your protagonists can be human, alien, animal, vegetable, mineral, or some combination thereof. But there is one thing that binds all these stories together, and it is printed right up front, “on the tin,” so to speak. That is science. And in writing stories about the hard sciences, no one did it better than Hal Clement.

Hal Clement shook the SF community with the publication of his very first story in Astounding Science Fiction, “Proof,” which featured aliens who lived inside a star. Editor John Campbell loved stories where science was at the center, and Clement delivered precisely that kind of adventure: rooted in sound science, but stretching the bounds of imagination. During his career, he had a profound impact, not only on the readers of his work, but on his fellow writers of science fiction.

About the Author

Harry Clement Stubbs (1922-2003), better known by his pen name of Hal Clement, was one of the great writers of the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Four of his stories appeared in 1942, when he was a twenty-year-old astronomy student at Harvard. After graduation, he served as a pilot in the Army Air Corps, Eighth Air Force during World War II, flying 35 missions out of England in a B-24. He remained in the reserves after the war, retiring as a Colonel. His postgraduate education included master’s degrees in education and chemistry. He was a native and longtime resident of Massachusetts, and for most of his career was a science teacher at Milton Academy, an elite preparatory school.

Harry Clement Stubbs (1922-2003), better known by his pen name of Hal Clement, was one of the great writers of the Golden Age of Science Fiction. Four of his stories appeared in 1942, when he was a twenty-year-old astronomy student at Harvard. After graduation, he served as a pilot in the Army Air Corps, Eighth Air Force during World War II, flying 35 missions out of England in a B-24. He remained in the reserves after the war, retiring as a Colonel. His postgraduate education included master’s degrees in education and chemistry. He was a native and longtime resident of Massachusetts, and for most of his career was a science teacher at Milton Academy, an elite preparatory school.

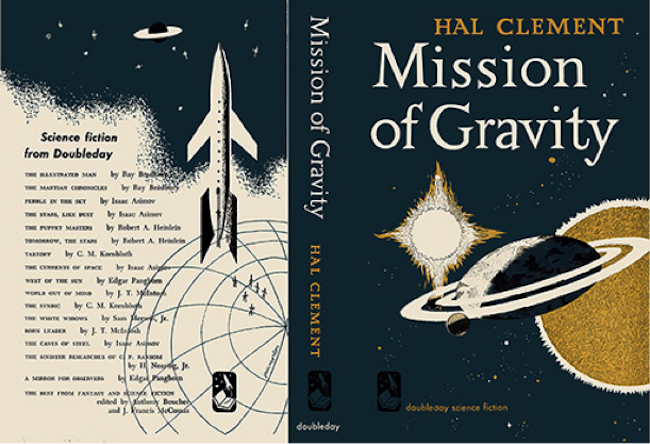

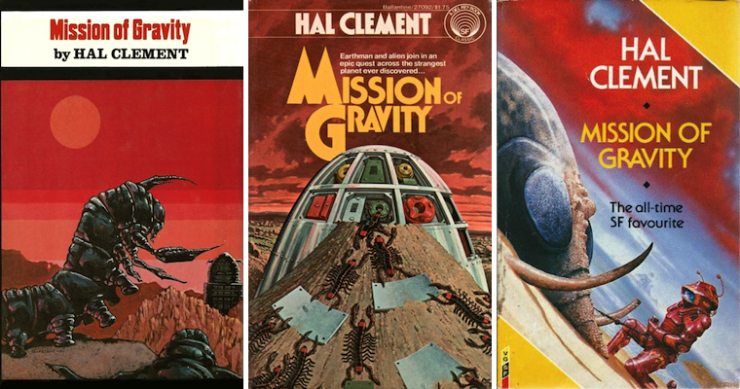

Clement’s first novel was my own introduction to his work, the juvenile novel Needle. It follows the adventures of a young boy who becomes host to a symbiotic alien being; a law enforcement official who is pursuing a fugitive. His most widely-known novel was Mission of Gravity, where he created the improbable high-gravity world of Mesklin. He also returned to that world for the novels Close to Critical and Star Light. Clement’s work was noted for being scientifically accurate, while at the same time playfully imagining what was possible at the boundaries of science. Science was definitely the center of the tales, with personal issues on the sidelines, and his characters are generally thoughtful and dispassionate (some might even say colorless).

Clement was not a prolific writer—his teaching career, service as a reserve officer, and volunteer work as a Scoutmaster was enough to keep anyone busy. The best of his work was collected by NESFA Press in a three-volume set entitled The Essential Hal Clement. He enjoyed taking part in SF conventions, especially those on the East Coast that he could attend without too much travel.

Clement’s recognition from the science fiction community was largely in the form of lifetime awards, not awards for individual stories. He was selected to join the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame in 1998, and he was named as a Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America Grand Master in 1999. He was known within the SF community as a generous person, free with scientific advice to those who asked for it.

The Joy of Science Fiction Conventions

Especially in the early days of SF fandom, back before the Internet, the life of a science fiction fan could be a lonely one. In a typical high school class, there might be a few dozen of your classmates who read comic books, and perhaps a handful who read science fiction. It is no wonder that fans began to gather together with like-minded friends, traveling further and further to attend SF conventions, or ‘cons’ as they came to be called. These gatherings soon developed their own language; those who did not attend were called ‘mundanes’ and SF-related singing became known as ‘filking.’ There were ‘huckster rooms’ where you could buy your favorite books, and autograph sessions where you could get a chance to exchange a few words with your favorite authors. And a major backbone of these gatherings was the panel discussion, where one or several authors or artists would gather before an audience and discuss a topic, which might center on a particular book, a scientific principle, ideas for cover paintings, or the business of publishing.

It was my father who introduced me to the world of cons, and it was at one of the first I attended that he said to me, “Harry is holding one of his world-building panels soon. You can’t miss that.” I didn’t know who Harry was, but followed my father to a function room, where he introduced me to his friend Harry Stubbs. It was easy to see why he and Harry got along: both were soft-spoken and bespectacled, both were WWII vets and reservists, and both were Scout leaders. It was only when the formal introductions were made that I realized that Harry was author Hal Clement. And then the panel began as people started throwing out world-building ideas. Would the planet be bigger than Earth or smaller? What would be its density, and composition? What would the surface temperatures be? Would water, or some other material, be the most common liquid on its surface? What kind of metabolism or forms of life would that support? And at the end, a new and unique setting for science fiction stories had been created.

I sat quietly, enthralled by the process, and amazed by the enormous difference all these changing parameters could make when it came to the ultimate form a planet (and the story set there) could take. And through it all, Harry would interject quietly. If you picked this average temperature, this would happen. If you had this length of year, and this axial tilt, here would be the results, and the variation in seasons. If you had a surface gravity of x, the atmospheric density would be such and such. There was some discussion, but when Harry spoke, and especially when he explained his reasoning and the facts he was working from, the issues were soon settled. And he had a marvelous talent for explaining things in such a way that people with a wide range of backgrounds could understand.

I had the pleasure to attend several world-building panels with Harry over the years, and they were always the highlight of the convention for me. I have attended many since then, as well, but they are not quite the same. I haven’t found anyone who thinks on their feet quite as well and as quickly as Harry, who has the same authority when they speak, and who can explain things as clearly as he could. Because of that, and because of the many authors he interacted with and advised over the years, he had a huge impact on the science fiction field, an impact far larger than his bibliography might imply.

The World of Mesklin

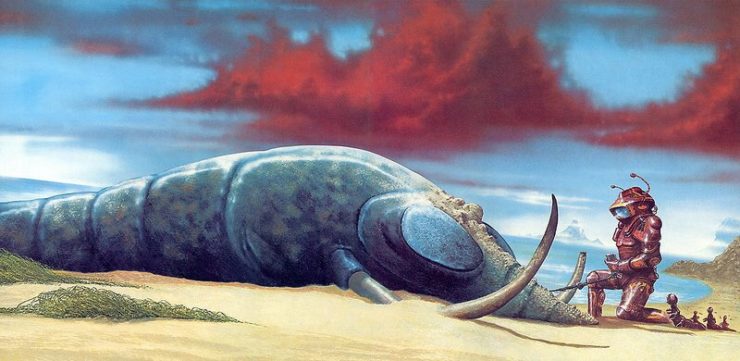

Clement’s first tale of the planet Mesklin appeared in Astounding in 1953. The possible presence of a super-Jovian world had been deduced from a wobbling of images of the star 61 Cygni, a wobbling later found to be an error. The mythical planet was assigned a mass equivalent to 16 Jupiters. Clement gave the planet a super-fast rotation, with days of only 17.75 minutes. All planets are wider at the equator than the poles because of the centrifugal force of their rotation, but Mesklin is compressed almost into a disc. This causes the surface gravity to vary widely, with 3G being experienced at the equator and a staggering 655G experienced at poles. The planet is a good deal colder than Earth, with methane seas and an atmosphere made up largely of hydrogen. Its intelligent life forms live mainly in the intense gravity of the polar regions, and resemble larger versions of the centipedes of Earth. Because of the gravity, they do not build high structures, and because of the atmosphere, they do not have fires. Despite these limitations, they have become adept at navigation, and have explored quite a bit of the planet by sea. Because of the composition of the atmosphere, Mesklinites look at their world as a giant bowl, since from their viewpoint, they can see the horizon curving upwards, rather than down (an effect that is sometimes seen at sea here on Earth). The specific characteristics of the Mesklinites go largely unexplored—Clement is silent on their exact biology, their social structures, and reproduction.

Mission of Gravity

The book opens with the Mesklinite trader, Barlennan, master of the ship Bree, which is more a collection of rafts than a single vessel like you would find on Earth. He has traveled to the far lands of the equator in search of rare goods and fortune, and instead has discovered mysterious visitor Charles Lackland. While the Mesklinites are experiencing a remarkable lightness, Charles is suffering under more weight than his kind were intended to endure. The Mesklinites call Charles and his kind “Flyers,” because they have descended from the sky. As the story begins, Barlennan and others have already learned the human’s language, their own speech spanning frequencies that the human ear cannot capture. That effort could have made for an interesting tale, but it is not the story Clement wants to tell.

Clement may have journeyed to the furthest reaches of his imagination to create the Mesklinites, but he didn’t have to travel very far to find a template for the personalities of Barlennan and his shipmates. They reminded me strongly of the old Yankee traders and sailors whose memories are kept in places like Mystic Seaport, crafty and clever, and it’s not a stretch to imagine Clement, as a Massachusetts native, casting in that direction for inspiration. They are also, like the human explorers in the story, exclusively male. But they also demonstrate more personality than the human visitors, who are a bland bunch, brave and determined, but almost interchangeable.

Lackland has convinced Barlennan to travel to the pole, where a human probe has landed, but because of the gravity is unable to lift off again. The humans are desperate to collect the information from that probe, but need native help to do it. Barlennan sees this journey as an opportunity not only to travel to unknown lands where exotic trade goods can be gathered, but also a chance to gain valuable knowledge from the humans.

Clement cleverly pushes not just Lackland, but also Barlennan, into unfamiliar territory. It’s not only the humans that are learning about this new world—the crew of the Bree are learning, as well. This allows information on Mesklin to flow naturally into the narrative, instead of being delivered in one expository lump. The story is rich in detail and information, but it never feels like the information is forced upon us.

We follow the protagonists as the humans give the Mesklinites radios and TV cameras that will be used to communicate throughout the journey, and record data when they reach the probe. Lackland uses a tank-like crawler to get around, and Barlennan rides on top of it, learning the advantage of height of eye. But when Lackland leaves the crawler, he finds that mixing Earth and Mesklinite atmospheres can have disastrous consequences, and only the creativity and determination of the natives can save him.

They map out the best path to the polar region where the human probe landed, and decide that an overland trip is required. Lackland agrees to use the crawler to tow the Bree over land, and they encounter a strange city built by cousins to Barlennan’s people. They lower the raft segments of the Bree down a cliff to an estuary, and the vessel sails on to uncharted waters. They find huge beasts that could never survive in the higher latitudes, and even Mesklinites who have learned to fly using gliders. Guided by the humans, Barlennan and his crew trade and battle their way across the world, slowly making their way toward the polar regions. By the journey’s end, they have learned things they never could have imagined, and done things they would have thought impossible when they started out. And the humans also learn a valuable lesson in dealing with the Mesklinites—greater knowledge does not mean greater intelligence or greater cleverness. In the end, it is a full partnership between the two groups that achieves their goals.

Final Thoughts

Hal Clement was an influential writer, bringing bold scientific extrapolation to the field to a degree that it had never been done before. He raised the bar for all writers who followed him, but also devoted himself to helping others vault that bar by sharing his knowledge. And he was a gentleman, generous with his time, and an example to others in his leadership. Mission of Gravity was a game changer, and at the same time, an engaging and clever tale.

And now it’s your turn. Have you read Mission of Gravity, or any of Clement’s other works, and if so, what did you think? Did you ever have the opportunity to see him at a convention or at one of his world-building panels? And where do you see his influence in the works of other authors?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.