“We may brave human laws, but we cannot resist natural ones.” –Captain Nemo in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Science and science fiction are indelibly intertwined, each inspiring the other since their modern birth in the Victorian Era. Both employ similar feats of the imagination—to hold an idea of a world in your mind, and test the boundaries of that world through experimentation. In the case of science, you formulate a theory and conduct a series of tests against that theory to see if it can be disproved by the results. In the case of science fiction, you formulate a reality, and conduct characters through the logical implications of that reality. Good science fiction, like a sound scientific theory, involves thorough worldbuilding, avoids logical inconsistencies, and progressively deeper interrogations reveal further harmonies. This series will explore the connection between the evolution of biology and science fiction into the modern era.

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea starts with a mystery. Reports mount of an unknown monster attacking ships the Atlantic and Pacific—a monster hundreds of feet long, with lights along its spine, a horn that can pierce the steel belly of a ship with ease, and the ability to travel from sea to sea at a remarkable rate. A naturalist and expert on sea life is recruited to aid in the hunting of this monster, only to discover that it’s not a monster at all, but an extraordinarily posh submarine. Adventures ensue until the protagonist and his companions finally escape Nemo’s gentlemanly tyranny. It is a story packed with interesting scientific infodumps and adventures to impossible places. It is a story that took Victorian dreams about the future of technology and used rigor and research to show what that reality could be.

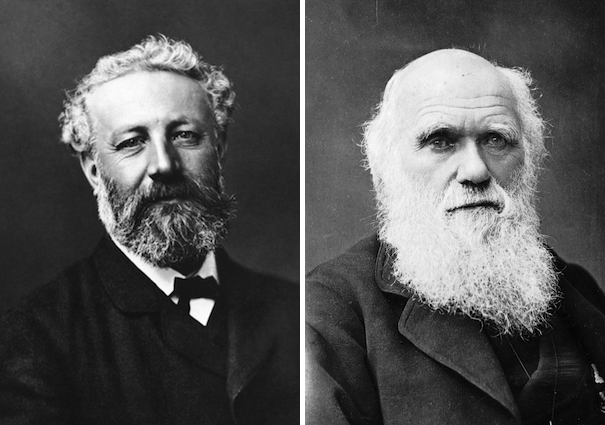

The Victorian era was a time of great change and discovery. For centuries, science had been slowly shaking off the fetters of the Enlightenment-era Catholic Church, which dictated that scientists were allowed to describe the world, but not to go deeper or risk excommunication or death. As a result, deeply controversial (at the time) works of scientific research into the natural world were starting to be published, such as Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, which provided evidence in the geological record that the world was vastly older than six thousand years, challenging a fundamental Catholic view on the nature of time and the universe. Additionally, the advances of the Second Industrial Revolution (steam power, the telegraph) fostered unprecedented speed and ease of communication and collaboration between scientists around the world. For the upper class, to which many of these naturalists and scientists belonged, it was a time of relative peace, optimism, prosperity, and discovery. The stage was thus set for the brilliant and curious minds of Jules Verne and Charles Darwin to change the future of science fiction and biology, respectively.

Verne was born to wealthy, upper-class parents. As a young man, he had an interest in geography and the sea, and emulated Victor Hugo, Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens, and James Fenimore Cooper in his early writing. He moved to Paris and began to work as a science and fiction writer, as well as a playwright. His exposure to science through his scientific writing inspired a lifetime of scientific interest, and during this time he envisioned a new kind of novel—a “novel of science.”

Darwin was also born to wealthy, upper-class parents, and as a young man, loved to collect beetles and go shooting. After a false start in medicine, he followed his father’s encouragement and went to school to become a parson. During his studies, Darwin read two highly influential works: Introduction to the Study of Natural Philosophy by Herschel, a scientific polymath, which argued that science reduces the complexity of the natural world into simple causes and effects based on universal rules; and Personal Narrative, a wildly popular work by Humboldt, a scientist and explorer, about his exploration of South America that combined precise scientific field work and observation. Darwin said of these books in his autobiography, “[They] stirred up in me a burning zeal to add even the most humble contribution to the noble structure of Natural Science.”

When Verne released Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea: A Tour of the Underwater World in 1863, he tapped into the same market as Humboldt’s aforementioned book and Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle. It was a way for Victorians to explore the world without ever leaving their sitting rooms and to understand the diversity within it, fueled by the naturalist desire to collect and categorize everything on the planet. The age of pure exploration was over, and Verne banked on his audience’s continued, unfulfilled thirst for discovery and novelty. Twenty Thousand Leagues took his readers to alien and unknowable places, with a naturalist as their guide, aboard a meticulously researched and detailed technological marvel. In fact, this was a common trope for Verne—to whisk his upper-class readers away from the societal upheaval and cultural change going on in the world around them, and back to a time of adventures in a mysterious locale, from which they would be safely returned to the shores of an unchanged reality at the story’s close. His were truly works that explored the “What” of future technologies, observation, and exploration—what wonders lay ahead, what might we find and create, using the latest scientific methods and discoveries?

Where Verne wrote in the tradition of description and observation characteristic of naturalist writing, Charles Darwin, following his own five-year cataloging and observation adventure aboard the HMS Beagle, began to see a bigger picture. While naturalists had primarily concerned themselves with taxonomy and determining the various varieties of different species, on his trip, he read two hugely impactful works: Lyell’s aforementioned Principles of Geology and Malthus’ An Essay on the Principle of Population, which observes that when a population grows exponentially, food sources only go geometrically, and argues that soon a population must outstrip its resources, leading to the necessary suffering of the poorest members due to the resulting competition. Everywhere Darwin looked, he saw the ghosts and echoes of these works in the ways in which world had morphed and changed—in the cliff faces, in the fossils he stumbled over of giant extinct relatives of the smaller South American species he could see all around him, and in the changing beak characteristics of the finches of the Galapagos. He noticed how species seemed to be specialized to certain areas, and how their distributions were affected by geological features, and also how these distributions had been interrupted by the introduction of “Old World” species to the American continents. He carried all these observations back to England, where he spent the rest of his life reading and speaking to everyone he could find about their own related observations. Over the next thirty years, he began to meticulously lay out an argument, one which he knew had deep-reaching implications, one that sought to provide an answer his own field’s central “What”—a question which had been stymied by the Church for so many centuries: what causes the variation seen in species?

The explanation Darwin came up with was the theory of natural selection, which argues the individuals of a species that adapt best to the environmental pressures they experience are more likely to reproduce and leave behind offspring that may eventually displace other, less successfully adapted members of the species. What is remarkable about his theory is that his observations include a number of genetic phenomena that Darwin had no mechanism to explain. He takes observations by geologists, paleontologists, other naturalists, breeders of all varieties, animal behaviorists and taxonomists, and manages to describe mutation, genetic linkage, sex-linked traits, ecological niches, epigenetics, and convergent and divergent evolution, all because he took in as many observations as he could and came up with a theory that fit best. Furthermore, because he had read Lyell’s work, he could see how these forces of selection could act over long periods to produce the diversity seen in every corner of the world. And from Malthus, he could see that competition within ecological niches, pressures from the environment and sexual competition seemed to be the forces shaping the adaptations seen in different species in different regions. Furthermore, Darwin achieved this, like Verne, by synthesizing his great passions, reading widely, and formulating an explanation that fit all of the facts available.

Darwin admitted to being a man who abhorred controversy. As such, he became a bit of a perfectionist. He was spurred to finally publish On the Origin of Species only after another naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, had excitedly sent him a draft of his own paper outlining a very similar mechanism to Darwin’s after his own travels all over the globe. Darwin and Wallace presented their findings jointly at the Linnean Society in July of 1858, and when On the Origins of Species came out the following year, all 1,250 printed copies sold out on the first day.

The book garnered international attention, and while not hugely controversial at the time, his careful avoidance of any discussions of human evolution, coupled with how his theory, lacking a mechanism of action beyond “environmental pressures,” became easily twisted in a society that took so much stock in Malthus’ argument about life being inevitably and necessarily brutal to the lower classes—so much so that it became a kind of warped moral duty to ensure the lives of the poor were as horrible as possible to prevent them from reproducing too much. It is out of this environment the concepts of social Darwinism and eugenics were born. Lacking a scientific explanation for the “How” of natural selection, a scientific theory was twisted into a sociological one that has had, and continues to have, far-reaching and disturbing implications.

Darwin is regarded as the father of evolutionary biology, and his legacy within the history of biology cannot be overstated. His body of work inspired scientists of his era to delve deeper into the mystery of hereditary, to figure out and investigate the mechanism of evolution, and to pursue the burning question of how so much diversity in the world had arisen in the first place. These questions encompass not only some wide-ranging sub-fields of biology, such as behavior and ecology, but as we shall see, directly led to the birth of the field of genetics.

Like Darwin, Verne’s legacy on the history of science fiction also cannot be overstated. His scientific romances and extraordinary voyages left an indelible stamp on the field, particularly upon Hugo Gernsback who, in his issues of pioneering science fiction magazine Amazing Stories in the early 20th century, ran reprints of Verne’s work in order to expose more people to the author’s unprecedented works of “scientification.” Verne anticipated the invention of submarines, deep-sea exploration, and flight both on earth and in space. While Poe and Shelley had both published fiction prior to Verne that included the trappings of contemporary science, no one before Verne had paid such profound and meticulous attention to the scientific detail. He truly was the first purveyor of what has since evolved into hard science fiction.

However, Darwin and Verne only provide part of the picture, in terms of what their fields would become—they both answered the essential question of the “What.” Darwin was still missing the key to his question of how hereditary works, however, and science fiction was destined to become far more than just a cataloging of potential technological innovations over an adventure story backdrop. In our next installment, we will be looking at two individuals who provide us with solutions to the “How”: H.G. Wells and Gregor Mendel.

Kelly Lagor is a scientist by day and a science fiction writer by night. Her work has appeared at Tor.com and other places, and you can find her tweeting about all kinds of nonsense @klagor