What makes a work of art “Shakespearean”?

It’s a stranger question than we might think, mostly because no one agrees or realizes that they don’t agree. It’s a term that we apply across the artistic gamut, from plays to films to novels, for every age group and every genre. It seems a clever shorthand because practically everyone in the modern world knows who William Shakespeare is, and has at least read a play or seen one up close at some point in their life.

But that doesn’t actually clue us into what Shakespearean means.

It does seem a term that falls into two categories: (a) a term used to denote high quality, or (b) a term used to denote a certain type of story. Sometimes it is used to indicate both of these things at the same time. But we see it everywhere, and often reapplied past the point of meaning. When Marvel Studios released the first Thor film in 2011, it was heralded as Shakespearean. When Black Panther was released earlier this year, it was labeled the same. Why? In Thor, the characters are mythological figures who speak in slightly anachronistic dialects, and family drama is the three-dollar phrase of the hour. Black Panther also contains some elements of family drama, but it is primarily a story about royalty and history and heritage.

So what about any of this is Shakespearean?

Fair to say the term is overused. Claiming that something is Shakespearean because people talk formally is just plain silly. And Shakespeare didn’t have a claim on family drama or epic, kingdom-altering stakes when he was writing his plays, nor was he the first one to employ those devices—writing the lives of gods and kings is one of the most common storytelling choices of all. You might as well say that that every tale working with those themes is “Beowulfian” or “Ganeshian” or “Anansian”.

To suggest that the term is indicative of automatic and unassailable quality is equally misguided. No matter how incredible Henry V or Much Ado About Nothing or Sonnet 116 may be, not everything that Shakespeare wrote was all that and a pile of gold. He misstepped on occasion. Sometimes he overwrote. And what he wrote wasn’t intended to be purely highbrow; he wrote for common people, the masses, even while he wrote for royalty and nobility. He was the king of dirty jokes. Some of his most infamous zings are deliciously petty. It’s strange to watch people constantly use Shakespeare as a stamp of automatic quality when taking the term to mean “pedestrian and fun” is equally applicable.

The same goes for plots that even slightly mimic anything that Shakespeare ever wrote. The writers of The Lion King admitted to recognizing certain similarities between their tale and Hamlet, once they decided that Scar would be Mufasa’s brother. They even leaned on that similarity for a time while scripting before dispensing with it. But people still call out The Lion King for being an animated version of Hamlet, and argue the point constantly. Why? Because an uncle kills his brother for the throne and is eventually unseated by his nephew? It’s a pretty basic comparison. Plenty of stories do this kind of thing. Unless Simba actually struggles with madness, I’m not seeing much of a parallel.

The truth is, when most people say “Shakespearean” they might as well say “wow, this story is very human.” Which is great… but not particularly specific to Shakespeare or the stories he personally chose to tell.

So what about the stories that do spring directly from Shakespeare’s works?

There are many tellings and retellings and continuations and sideways looks at the works of William Shakespeare. Some of them are entirely direct in their commentaries on the Bard. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is an oft-tagged favorite. So is I Hate Hamlet. Some of these explorations delve even deeper, and then you get works like Goodnight Desdemona, Good Morning Juliet. (I highly recommend that one, if you’ve never read/seen it.) Getting a chance to see modern plays inspired by Shakespeare’s is a delightfully meta experience in and of itself, and they are often sharp in their analysis, if that’s your beat.

Science fiction and fantasy genres give us the ability to examine Shakespeare’s work through a new lens, made even easier by how often his works included magic, myth, and mystery. If you’re a fan of the classics (in film, that is), you may have noticed some similarities between Forbidden Planet and The Tempest, and you wouldn’t be wrong. Aldous Huxley famously quoted the same play for the title of Brave New World. Dan Simmons’s work frequently borrows from Shakespeare, and Harry Harrison’s “A Fragment of Manuscript” reimagines the origins of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. One of the best volumes of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman involves putting on a production of Midsummer for a faerie audience; the reality and the dream colliding to create a brand new performance.

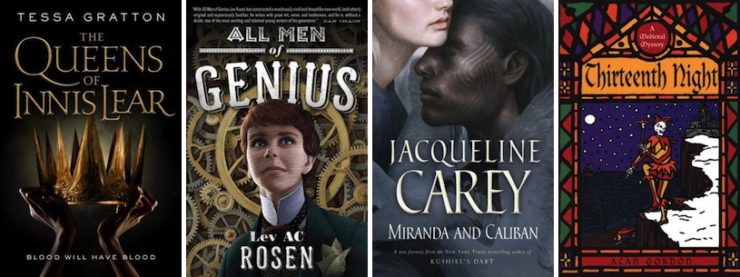

These genre-fied versions can also put a spin on the stories that didn’t grab you the first time. Tessa Graton’s The Queens of Innis Lear is a brand new look at one of my least favorite Shakespeare works, King Lear. By examining characters who may have deserved more attention in the play—namely Lear’s daughters—the book reframes the power dynamics of the original in truly fascinating ways. In another work that casts familiar characters in a new light, Lev AC Rosen adapted Twelfth Night into his steampunk Victoriana novel All Men of Genius. Jaqueline Carey’s Miranda and Caliban and Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed tell their own versions of The Tempest. Stories like these can help renew material that feels stale, or elevate parts of Shakespeare’s work that we already adore.

And what about the Bard’s stories that you didn’t want to leave? Plenty of plays and books continue to explore and expand in the space after Shakespeare’s curtain falls. Alan Gordon’s Thirteenth Night comes several years after Twelfth Night, and accompanies Feste the Fool for a brand new adventure. The upcoming Miranda in Milan by Katharine Duckett follows Prospero’s daughter in her days after their exile is ended, as she tries to navigate a new life in her father’s castle. If you find yourself reading and rereading your Complete Works of Shakespeare cover to cover, there are other avenues to pursue to find more story, more adventures with characters that you love.

However it is that you enjoy Shakespeare—through grand, vaguely inspired drama, or the more specific tales that engage with the worlds he created—there is plenty to immerse yourself in. Maybe don’t let people get away with calling every movie containing a royal family squabble “Shakespearean”, though. That’s a bit much.

Emmet Asher-Perrin is so excited to get her hands on Miranda in Milan, ya’ll. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

I’ve often wondered why the works of Shakespeare are often held as the highest form of entertainment, when much of his writing was created for enjoyment of the masses. That doesn’t take away from the power of the story, though; it heightens it by knowing what was then considered low-brow is now seen as something to aspire. Does that show an lesser sophistication among today’s audiences; or an greater appreciation of strong character and story that was overshadowed in the past by the spectacle?

Also, are expansions and derivatives of Shakespeare fan faction?

it heightens it by knowing what was then considered low-brow is now seen as something to aspire.

I’m not entirely sure that Shakespeare was ever considered low-brow. His plays were performed at Court, after all. The only low-brow thing about them, by the standards of the day, was that they were in English, and the language of the educated man was Latin. But Shakespeare wrote about classical subjects, even if he did so in English. They were widely popular, sure, but that’s not the same thing as being undemanding.

Dividing culture and entertainment into highbrow/lowbrow is more a modern thing than one of Shakespere’s era. It’s related to the mass-production of entertainment, costs, and class – it is highbrow to go to an orchestra concert, (lots of performers, live, so expensive to produce and consume) lowbrow to listen to a recording of a popular singer (one performer, with accompaniment, recorded and played back, so the cost to enjoy is quite low.)

For Shakespeare’s audience, the difference would likely be between a private performance, versus a public one. Also the size of the cast, the luxury of the costumes, etc. All performance was live, and ephemeral. The queen could command a large cast to put on the whole play, or many people could buy tickets to see a public performance of the whole play. Alternately, people better off than the general audience but not the queen might hire a smaller group of performers, to put on a reduced or modified version of the play, privately. Or a smaller public venue (e.g., a pub) might have a small cast put on a reduced performance, as a way to draw customers. The same for music – the queen could command an orchestra, while others could toss pennies to street performers, etc.

I tend to think of something as “Shakespearean” that has that universal appeal/adaptability. You can do a popular version of a Shakespeare play, modified for television, with updated language, or you can have a huge cast on stage for a live performance, and it still works either way.

THOR harkens back to KING LEAR and the “who does Daddy love best?” theme. Plus, it was directed by Sir Kenneth Branagh so Shakespearen.

@1. It wasn’t until the mid-Twentieth Century that the intelligencia considered popularity and accessibilty to a work to be a bad thing, and that’s really a stupid idea to most of us.

Shakespeare wrote to put butts in seats, and some of those people enjoyed dirty jokes, word plays, and violence. Others enjoyed other elements. He did both very well, and his ideas and words have resonated through the centuries so he’s considered the greatest writer of the English language.

And, no, using elements of Shakespeare or call-backs to the plays is not fan fiction in most cases because fan fiction tends to take the original elements but not really build on it or become something other than the original.

Calling something Shakespearean is often an effective riposte against “literary” snobs, who teach that real literature is about people sitting around a kitchen table, talking.

Shakespeare’s plays are full of Kings, Dukes, supernatural beings, magic spells, often set in exotic locations. Shakespeare also constantly violated the classical doctrine of unity of affect; that is, his tragedies have lots of jokes in them, and his comedies stop just short of leaving the stage strewn with dead bodies.

@4/MByerly: The idea of high and low literature is actually older than the 20th century. I recall the 19th century librarian who refused to have “that Dickens trash“ in his library. In Shakespeare’s time, his University-trained rivals larded their work with classical allusions; while his work was full of references to plants and animals, as statistical studies have shown. (And dirty jokes, which he could get away with, because the monarchs were fans.) Thus, John Milton refers to Shakespeare’s “native woodnotes wild”.

@5 Sure, there’s always been snobs. There’s also a constant wash and repeat as each new literary movement feels it must vilify and denigrate the literary movement it is replacing. But the institutionalized determination of what is and isn’t “literary,” and therefore worthy of being read is much newer. It originated when most publishers were owned by Ivy League old money, and literature professors started justifying their existence by insisting only books and theater that had to be explained by them for others to understand it was worthy.

@1–I’m not sure I follow your first question, but I’ll take a stab at it: “Does that show an lesser sophistication among today’s audiences?” In short, no. A major reason that Shakespeare’s works are not considered entertainment for the masses today is that they’re written in a 400-year-old dialect, making references the 1600s equivalent of pop culture. Things that everyone in London knew in 1600 are now things you need to take a college course to understand. (I’m sad I’ll never get to see the 2400s college classes on memes of the early 2000s…)

As for fanfiction, it depends on how you define fanfiction! By one count, Shakespeare himself was writing fanfiction–many of his plays were retellings of old stories. By that same count, Shakespeare retellings are fanfics of fanfics. By another definition, though, no. Fanfiction today has its own sets of tropes and genre conventions that don’t generally show up in traditionally published work. (I would argue that fanfiction today IS often building on its source material or becoming something other than the original, like Shakespeare himself.)

Well, this was a comment… essay maybe, and then suddenly wasn’t… not sure whether that was my computer or a glitch in the website, but… not rewriting it.

I was among those who referred to Thor as “Shakespearean” when it appeared, and I did so because it seemed to me that Kenneth Branagh had deliberately staged elements of the film to resemble a Shakespeare drama, and several of the performances appeared calculated to resemble an acting style that recalls classical Shakespearean theater (of which I’ve seen a lot). I did not and would not use the term to describe Black Panther; Shakespeare may have been an influence, but that film’s style is distinctively its own. [OTOH, there’s a bit of arguably Shakespearean riffing in Thor: Ragnarok, when we see Loki as Odin watching the play he’s commissioned featuring his own ‘heroics’.]

When I was actively reviewing, I also used “Shakespearean” from time to time, usually in one of two contexts: either to indicate that a work had borrowed some particular element from Shakespeare’s body of work (for example, Linda Haldeman’s The Lastborn of Elvinwood incorporates characters and ideas from Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream), or that it took place in a setting in which one might reasonably find Shakespeare as a character or influence on the characters (Armor of Light by Scott & Barnett, Ruled Britannia by Turtledove). I also recall one other case in which I invoked Shakespeare, wherein the author of a particular fantasy novel had written most of his dialogue in iambic pentameter, much of it capable of being read as blank verse (though not formatted as such).

Also, as regards Shakespearean fanfiction: I want to see this staged.

Part of the enduring appeal of Shakespeare is the simple fact that his works have endured, which some seem to misinterpret as having occurred due to inherently superior writing. In that sense, many attempts to label something ‘Shakespearean’ fall somewhere between wishful thinking and outright pretentiousness; without a genuine time machine (or at least a vehicle capable of traveling at relativistic speeds) we can never know which works will truly hold up for future audiences.

Perhaps the term should be reserved for those works which seem to capture a key element of why Shakespeare’s best plays are still relevant: being derived from and informed by particular moments, places, and cultures without being strictly tied to them. You can transport the Montegues and Capulets from Verona to Verona Beach, and maybe even ship Elsinore off to Arrakis, and those plays can still work without requiring too many other significant changes; the new settings, costumes, and props simply allow different aspects to be explored. Memorable personalities and momentous events certainly help, as do some inherent anachronisms and idiosyncratic speech patterns to provide a bit of distance from the (original) audience, but perhaps the ability for the story to survive shifts in time, space, and visual aesthetic may be more crucial to qualify as ‘Shakespearean’.

Hey, how about Poul Anderson’s A Midsummer Tempest? It’s so Shakespearean, it’s written in iambic pentameter.

Perhaps the term should be reserved for those works which seem to capture a key element of why Shakespeare’s best plays are still relevant: being derived from and informed by particular moments, places, and cultures without being strictly tied to them.

And this seems to be an attribute that Shakespeare has and others don’t have – like, for example, Dickens. Whether you love or hate Dickens, and personally I can’t stand him, his stories are all very rooted in place and time; you could update Romeo and Juliet to any number of settings, but I can’t imagine a modern-day Pickwick Papers or Bleak House working at all. Sure, you could rewrite heavily and end up with something vaguely similar in terms of plot, but it wouldn’t still be Dickens, in the way that Romeo + Juliet is still Shakespeare.

I may be letting my emotional attachment to King Lear, Richard II, and Lady MacBeth get in the way, but I think to call Shakespeare pedestrian is quite a stretch. Shakespeare did things with language and storytelling that no one did before, and many have failed to do since. Harold Bloom goes so far as to say that Shakespeare created modern consciousness in English. Shakespeare’s contemporaries, with maybe the exception of Christopher Marlowe, were pretty sad playwrights who could only write cliche and PEDESTRIAN characters, whereas Shakespeare’s characters speak and act like real people with real questions, undergoing real troubles.

To the question posed in the title, I would call something Shakespearean when it displays the same level of fearless storytelling that even Shakespeare’s worst plays, like Titus Andronicus and Henry VI 1,2,3, display throughout. Yeah, those plays are his worst and they are far from terrible, in fact they are better-told stories than most of English literature since then. People may not agree with the content of Shakespeare’s plays or with what the characters say, but isn’t that true of real people, too? There may be examples, but none of them can impeach the entire body of his work: Shakespeare’s plays simply tell stories in a way nobody else does. Whatever that Shakespearean quality is, it’s hard to verbalize, but it’s easy to see when it’s there.

ajay@13

On Dickens, I will note that there have been a LOT of variations of “A Christmas Carol”.

Ian@11: “Part of the enduring appeal of Shakespeare is the simple fact that his works have endured, which some seem to misinterpret as having occurred due to inherently superior writing.”

Sure, it’s partly because they endured. But they endured because not only are they great – but they speak to everyone.

To add my two cents, as a Frenchman and French literature major : “Shakespearian” has yet another meaning here on the continent. See, in the 17th Century, classical theater in France was extremely codified, with what writers called “three unities” (one place, one time, one plot). They also added rules about a “unity of tone” (either “all tragic” or “all comic”, but no mix between the two) ; moreover, the protagonists had to be noblemen and women, and all had to speak in specific, “noble” meter ; and the action had to be “noble and lofty” all the time. While these rules allowed them to produce fantastic tragedies in their time, they also hindered creation, because they were so restrictive. Classical writers loathed Shakespeare ; “British theater” was considered messy, unruly, full of “lowly characters” who spoke in a “lowly manner”, and – blasphemy ! – constantly mixed comedy with tragedy. Also, 17th Century France basically invented this divide between “popular fun”, made for the masses, and “royal entertainment”, which was of course the only “real” literature. England never had that problem, and that’s what made Shakespeare such a genius. It was not until the Romantics that the rest of Europe rejected classical tragedy and started having a boner for Shakespeare. Victor Hugo, for instance, was the first to start mixing commoners and noblemen, verse and prose, comedy and tragedy (and literary criticism almost burnt him at the stake for it at first).

Interestingly enough, I noticed that this trend is so deeply ingrained that it is still visible in today’s fantasy. Something I really, really admire in UK/USA fantasy, is its ability to weave a complex tapestry of high and low characters, mixing lofty and popular speech, comic and tragic tone, etc. That’s what is really “Shakespearian” about it, too. There’s a lot of fantasy still being written in France, but it still shows traces of the old mould – always serious, always grave, unable to mix the Jest with the Lofty. While a saga like Erikson’s Malazan world is in my opinion fully shakespearian, with its constant coexistence of dark, tragic figures who are thousands of years old, and whose story bring tears to me, with common soldiers and their realistic, no-nonsense, cynical jokes.

“Unless Simba actually struggles with madness, I’m not seeing much of a parallel.”

The Lion King becomes much more Hamlet-like if you have a couple of drinks before watching it and assume that Timon and Pumba aren’t actually real, but are voices in Simba’s head that drive him to a “hakuna matata” state of inaction for his entire adolescence.

This is not the fan fiction you’re looking for. This is the fan fiction you’re looking for: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Shakespeare's_Star_Wars:_Verily,_a_New_Hope

The love of and constantly inventive use of language should be the key to “Shakespearian” whether displayed in crude puns muttered at the lap of Ophelia or in discounting the stars to Horatio in the most sublime metaphorical description of the heavens. If it ain’t got poetry, it ain’t Shakespearian.

Do you know Dogg’s Hamlet, Cahoot’s Macbeth? The opening is built around a performance by students to whom 20th-century English is more alien than 16th-century English is to us; the affectless, babbling line-readings are priceless or painful, depending on how you remember people in your foreign-language classes trying to read out loud material they clearly didn’t understand.

@21–I do not! But I’ll have to check that out–it sounds amazing.

Is there anything any style or author that might be a popular or quotable in 400 years time as Shakespear is today? Or does ST-TNG have it right with Picard quoting the Bard well into the 24th century?

#23: That’s a two-part question, really. One issue is the survivability of any given individual work, with so very much new work now being created — what’s going to be remembered all save for the most widely popular material? Alternately, though, it’s what epigrams and snippets may survive outside the context of the works in which they appear, by virtue of being sufficiently memorable or timeless.

To the extent that there’s any overlap in the answers, I think fantasy/SF has some advantage in that it often works in prose styles that attempt a degree of timelessness. Bits of Tolkien, certainly, may endure, very possibly certain elements of the Madeleine L’Engle canon, and — if I had any say in the matter — the Oath from Diane Duane’s “Young Wizards” series.

According to Tony Stark ‘Shakespearean’ means characters wear capes.