We’re told to never judge a book by its cover, but we often do anyhow. Cherie Priest’s Boneshaker was a book I judged by the cover: it had one of the first self-consciously steampunk covers, depicting the heroine wearing brass goggles, their lenses reflecting airships in flight. It veritably screamed steampunk. Scott Westerfeld’s cover blurb said the book was “made of irresistible,” while Mike Mignola quipped it was a mash-up of Jules Verne and George Romero. There was no steampunk book released with more hype in 2009 than Boneshaker, and steampunk enthusiasts, myself among them, placed it at the top of their “to be read” pile. Perhaps I was the victim of ridiculously high expectations resulting from the gorgeous cover and the pre-release hype, as I was ultimately underwhelmed. I wondered if I’d missed something. After all, many readers loved it. It was nominated for several prestigious SF awards. It won a Locus for best SF novel. At that point, I was convinced I’d missed something, and vowed to let Wil Wheaton and Kate Reading read it to me on audiobook at my earliest convenience. I needed another experience of it, since I’d speculated in my review of Boneshaker that since, “Priest still has the hands-down best short description of steampunk in existence, I’m hopeful she may yet write the hands-down best-steampunk-with-intention novel.”

My “earliest convenience” to revisit Boneshaker is yet to arrive, but I’m not sure it matters anymore: Cherie Priest’s Dreadnought just tied Scott Westerfeld’s Leviathan for my “best-self-conscious-work-of-steampunk.” Dreadnought is everything I loved about the first third of Boneshaker, without any of the slower-pacing that plagued the remaining pages. At points, Dreadnought seemed written in response to the critique I’d voiced for Boneshaker. In Boneshaker, I found Briar’s voice stronger than Zeke’s; in Dreadnought, Priest focuses on one point-of-view, Mercy Lynch, who fits the bill of “strong female lead” in numerous ways (I often compared her with Renée Zellweger in Cold Mountain). Boneshaker’s plague-carrying revenants (zombies for shorthand) were too benign, lacking the sort of threat post-Resident Evil undead must possess to invoke a sense of fear in today’s zombie-jaded reader; Dreadnought’s zombies crawl onto the page in stages, but once they’ve arrived, they’re scary as hell: faster, meaner, and hungrier than their Seattle-based counterparts. And finally, the slow-paced meanderings in the Seattle underground have been replaced with a steampunk Trains, Planes and Automobiles as Mercy rushes to the West Coast via river, rail, and of course, airship.

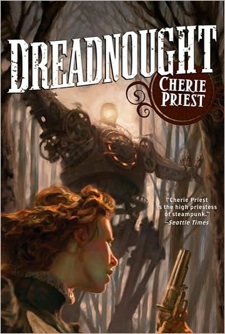

This is as much as I can say without leaking spoilers. While some books give the game away with their cover, Dreadnought does a fine job of keeping its secrets, so long as you don’t bother reading the synopsis on the back cover. I was so immersed by Priest’s prose in the opening chapter that I never bothered to read the synopsis, and was blissfully unaware of what the Dreadnought was. (I must digress to highlight the opening scene in a Civil War hospital, which is gorgeous writing. When you get to the line “She carried it with her, always,” you’ll know what I mean.) Based on the cover, you’d think it was a steampunked version of the Iron Giant. Even after I knew what the Dreadnought was, my ignorance of the synopsis kept me in suspense as to how Mercy’s journey would bring her face-to-face with the Dreadnought. The result was glorious fun, and by the end, I wondered if Cherie Priest plays Dungeons and Dragons, and how much she’d charge to be my DM.

Readers familiar with my blog will find my enthusiasm uncharacteristic. I usually engage in a close-reading of a text, relating it to my definition of steampunk as an aesthetic that employs three elements: technofantasy, neo-Victorianism, and retrofuturism. Tor editor Liz Gorinsky calls the Clockwork Century books “Steampunk 102,” implying Priest is doing the next thing in steampunk. I wasn’t convinced of this in reading Boneshaker, but after reading Dreadnought, I’m more than inclined to agree with her. Priest is messing up my dissertation. This isn’t technofantasy, at least not in the way the Darwinist fabricated “beasties” of Westerfeld’s Leviathan and Behemoth are—Priest doesn’t resort to fictional fuels such as aether, phlogiston, or cavorite. Instead, her anachronisms are powered by coal, diesel, and possibly electricity. This might not seem a big deal for the cursory reader of steampunk, but to someone who’s read over forty steampunk novels for research, it’s a revelation. Contrary to popular conceptions, there really isn’t a lot of steam-tech in steampunk writing. For reasons either literary or lazy, many steampunk writers would rather invent a fuel than research it. Priest’s done her research, and it shows in more than just the presence of fossil fuels.

As a Canadian, I lack even a rudimentary understanding of the American Civil War. While history buffs might fault Priest for her “real” history, this steampunk scholar applauds her alternate history. Again, this differs from a lot of steampunk in two ways, both related to the second aesthetic element of neo-Victorianism. I chose that term over many others to convey the idea of how steampunk evokes the nineteenth century, though may not necessarily take place in that period. There’s a lot of steampunk that just looks or feels like the nineteenth century, but takes place in alternate worlds like Stephen Hunt’s Court of the Air, or future times, as in Theodore Judson’s Fitzpatrick’s War. When steampunk is actually set in the nineteenth century, it usually takes place in Britain or Europe. On the page, steampunk in America is rare. Rarer still is genuine alternate history, where enough research has been done to create the level of verisimilitude of Gibson and Sterling’s Difference Engine which lead some critics to conclude it was hard SF, not steampunk. Dreadnought is set in an alternate nineteenth century America that could have been, at least between the covers. Compare that with the Victorian Ragnarok of S.M. Peters’ Whitechapel Gods, or the clockwork planet of Jay Lake’s Mainspring, and you’ll find a railway less traveled. Priest is engaged in a world-building exercise, but unlike many steampunk writers, she’s not cutting corners laying the tracks for this alternate history: while Mercy Lynch is a strong female, she doesn’t live in a world of egalitarian emancipation. Two pages after we learn of abolition in the Clockwork Century, Mercy faces the stigma of being a “woman traveling alone” (pg. 114). While Priest is clearly neither sexist nor racist, many of her characters are. Priest hasn’t just researched the events of nineteenth-century America, she understands how people thought at the time. Her characters live and breathe in the complex web of post-abolition laws and pre-abolition ideologies.

When I turn to retrofuturism in steampunk, I’m usually talking about how the past imagined the future insofar as technology. In talking about retrofuturism in Dreadnought, we see the past imagining a social, not necessarily technological future. To be certain, Dreadnought has its share of steampunk tech: but Mercy Lynch is only interested in that technology for how it will get her to her destination. There are few discussions about how steampunk technology will make life better. Instead, Priest’s retrofuturism is tied to that complex web of race and gender in the nineteenth century. Her trump card in both books is strong female characters transcending nineteenth century gender stereotypes and limitations, without oversimplification. Her setting of America permits her to posit spaces where equality of gender and race isn’t sidetracked until the Suffragette or African American civil rights movement, but finds purchase on the frontier of a nation still in process of becoming. I’ve been waiting for steampunk set in America to run with these ideas, and it’s a fine thing to finally see it being realized.

Yet for all my high-falutin’ talk about the steampunk aesthetic and complex issues, I hope my readers haven’t forgot that I was initially gushing about enjoying a page-turner. With Dreadnought, Priest has succeeded in writing a thoroughly engaging piece of adventure fiction, the kind Michael Chabon championed in “Trickster in a Suit of Lights,” which serves to entertain as well as stir things up. Two months ago, I was the guy saying Cherie Priest is overrated. I’ll be eating crow over the next few months, but I’ll be eating it with a smile on my face, hidden behind the cover of Dreadnought.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.