Winding Down the House

I want to destroy steampunk.

I want to tear it apart and melt it down and recast it. I want to take your bustles and your fob watches and your monocles and grind them to a fine powder, dust some mahogany furniture with it and ask you, is this steampunk? And if you say yes, I want to burn the furniture.

Understand, I want to do this out of love. I love what I see at steampunk’s core: a desire for the beautiful, for technological wonder, for a wedding of the rational and the marvelous. I see in it a desire for non-specialised science, for the mélange of occultism and scientific rigour, for a time when they were not mutually exclusive categories. But sadly I think we’ve become so saturated with the outward signs of an aesthetic that we’re no longer able to recognise the complex tensions and dynamics that produced it: we’re happy to let the clockwork, the brass, the steam stand in for them synecdochally, but have gotten to a point where we’ve forgotten that they are symbols, not ends in themselves.

Now, I am a huge fan of the long nineteenth century. I am a scholar of the long eighteenth century, which, depending on whom you ask, begins in the seventeenth and overlaps with the nineteenth, because centuries stopped being a hundred years long in the twentieth–which is, of course, still happening, and began in 1914. But the nineteenth century holds a special place in my Lit Major heart. When, about ten years ago, I began to see the locus of the fantasy I read shifting from feudal to Victorian, swapping torches for gas lamps, swords for sword-canes, I was delighted. I was excited. There was squee.

I could write about this, I thought. I could write about how steampunk is our Victorian Medievalism–how our present obsession with bustles and steam engines mirrors Victorian obsessions with Gothic cathedrals and courtly love. I could write about nostalgia, about the aesthetics of historical distance, and geek out!

And I could. I have, to patient friends. But I’m not going to here, because I think we’re past the point of observing what constitutes a steampunk aesthetic, and should be thinking instead of deconstructing its appeal with a view to exploding the subgenre into a million tiny pieces. We should be taking it apart, unwinding it, finding what makes it tick–and not necessarily putting it back together in quite the same way. In fact, maybe we shouldn’t put it back together at all.

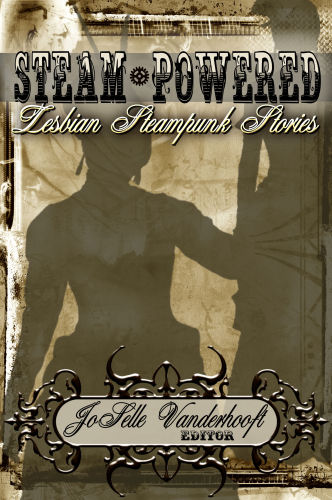

A case in point: I was recently asked to contribute a story to Steam-Powered: Lesbian Steampunk Stories, an anthology that does what it says on the tin. I wrote a story in what, to my mind, would be a steampunky Damascus: a Damascus that was part of a vibrant trading nation in its own right, that would not be colonised by European powers, where women displayed their trades by the patterns of braids and knots in their hair, and where some women were pioneering the art of crafting dream-provoking devices through new gem-cutting techniques.

A case in point: I was recently asked to contribute a story to Steam-Powered: Lesbian Steampunk Stories, an anthology that does what it says on the tin. I wrote a story in what, to my mind, would be a steampunky Damascus: a Damascus that was part of a vibrant trading nation in its own right, that would not be colonised by European powers, where women displayed their trades by the patterns of braids and knots in their hair, and where some women were pioneering the art of crafting dream-provoking devices through new gem-cutting techniques.

Once I’d written it, though, I found myself uncertain whether or not it was steampunk. It didn’t look like anything called steampunk that I’d seen. Sure, there were goggles involved in gem-crafting, and sure, copper was a necessary component of the dream-device—but where was the steam? My editor asked the same question, and suggested my problem could be fixed by a liberal application of steamworks to the setting. Who could naysay me if my story had all the trappings of the subgenre?

Syria, you may be aware, is a fairly arid country. There are better things to do with water than make steam.

So to add that detail would have meant acknowledging that steampunk can only occur in Victorian England—that it is bound to a time and a place, without which it must be something else. It would have meant my Damascus would be London with Arabic names tacked on, and that Syria could not participate in the exciting atmosphere of mystifying science that characterised Britain in the same period without developing precisely the same technology. It would mean that the cadence of my characters’ speech would need to change.

I changed other things. I gave my protagonist an awareness of world politics. I raised the stakes of the technology she was developing. I tried to make my readers see that the steampunk with which they were familiar was happening somewhere within the bounds of this world, but that I would not be showing it to them, because something more interesting was happening here, in Damascus, to a girl who could craft dreams to request but rarely dreamed herself. And my editor liked it, and approved it, and I felt vindicated in answering the question of whether or not it was steampunk with, well, why not?

I submit that the insistence on Victoriana in steampunk is akin to insisting on castles and European dragons in fantasy: limiting, and rather missing the point. It confuses cause and consequence, since it is fantasy that shapes the dragon, not the dragon that shapes the fantasy. I want the cogs and copper to be acknowledged as products, not producers, of steampunk, and to unpack all the possibilities within it.

I want retrofuturism that plays with our assumptions and subverts our expectations, that shows us what was happening in India and Africa while Tesla was coiling wires, and I want it to be called steampunk. I want to see Ibn Battuta offered passage across the Red Sea in a solar-powered flying machine of fourteenth-century invention, and for it to be called steampunk. I want us to think outside the clockwork box, the nineteenth century box, the Victorian box, the Imperial box. I want to read steampunk where the Occident is figured as the mysterious, slightly primitive space of plot-ridden possibility.

I want steampunk divorced from the necessity of steam.

Amal El-Mohtar is a Canadian-born child of the Mediterranean, currently pursuing a PhD in English literature at the Cornwall campus of the University of Exeter. She is the author of The Honey Month, a collection of poetry and prose written to the taste of twenty-eight different honeys, and the winner of the 2009 Rhysling Award for her poem “Song for an Ancient City.” Find her online at Voices on the Midnight Air.

Image of spherical astrolabe from medieval Islamic astronomy courtesy of Wikipedia.

This just so much. I want to see stories that focus more on the alternative history (with politics and such) and not on bustles and goggles. And I really want to check out that short story you mentioned, was it published in the anthology after all?

It’s your world. If it doesn’t “fit” someone else’s idea of what SP is, that’s fine. They can read someone else. Everyone has their favorites.

Lit is like that, esp. genre fiction. When I was in school the SF crowd was divided between the Arthur C. Clakre/Douglas Adams fans. Was SF serious and realistic, or saterical and funny?

Why can’t it be both? No one owns a motif, but you can own your vision of it.

YES! Thank you for articulating this point so well. I’ve felt strongly that the recent surge in Steampunk popularity has been fueled more by an aesthetic appeal for brass and cool gadgets than the many fascinating and diverse ideologies of punk culture. Let’s remember that being punk isn’t just about looking cool, it’s also about individual freedom, anti-establishment views, and a rejection of materialism and social injustice. Otherwise you’re just a poser.

As a historian myself, I have to agree and disagree with you on the length of Centuries. Yep, they have started to bleed quite a bit (I’d say that the 18th Century ended about 1814 or 15 myself) but oddly enough, I’ve always thought that the 19th Century ended and the Twentieth Century began in 1900 with the publication of Die Traumdeutung (The Interpretation of Dreams) by Freud. That was so obviously the end of Victorian thought.

Excellent piece. Your objective is fantastic, in all senses of the word. The idea of deconstructing steampunk not to see how it works, but to understand all of the stories and tropes and wonders that it misses, is a fabulous idea. The question then becomes how to address the tension between retrofuturism and the idea of steampunk itself; how do we re-draw the lines? Or do we just say “póg ma thoin!” to the Victorian trappings and go exploring?

I vote for the latter myself, which is what it seems you did with your story; push the boundries, turn some assumptions back onto themselves, and create a new niche. I’m working on a short story right now that, ideally, will do something similar, if from a different perspective, and that requires me to explore a world and history that I am unfamiliar with (in this case, turn-of-the-20th-century India), to write about the expulsion of the British about 40 years earlier, partly due to an increasing reliance on steampunk tech, and partly due to indigenous resistance creating more leverage to expel them. We’ll see how it turns out.

I’d love to read the story: is that “To Follow the Waves?” I see that the pub date is pushed back to January 2011, but it sounds like a promising anthology, and I hope to get a copy when it does come out.

And I must say, Tor.com is doing a great job of posting provocative, thoughtful essays on Steampunk in the Fortnight. Thanks to all of the writers and to the site for publishing them!

“and I want it to be called steampunk.”

Your retrofuturism sounds fascinating! But insofar as terms like ‘steampunk’ exist to enable communication, which requires that speaker meaning and listener meaning be relatively close to prevent talking past each other, you don’t get to just redefine terms on your own. What you’re doing is retrofuturism, and it sounds great, and there should be more encouragement of the broader genre. But steampunk is just the wrong word for it. Steampunk without steam is just punk.

Well said. Very well said. I saw a crafter, somewhere in the internet aether, refer to steampunk as steampulp and I think it’s a better term. Steampunk is to much about goggles and Victorian England these days. It’s why I moved to the Weird Western. This article has done well in giving me further nudging to finally get my weird west/steampunk/adventure series underway (after nanowrimo though as I have other plans first). In the world I made for that, there isn’t an overabundance of steam-tech or clockwork. It’s there, it has a presence but there’s so much more to that world.

I have a story in the same anthology, and I too wondered if it was really steampunk, given that there was no steam and that the machines in the story were of unknown origin and maybe not built by humans at all. Not to mention the lack of goggles, airships, and corsets!

I came to the conclusion that steampunk is a genre defined more by aesthetic rather than specific elements. You can take away the steam, and you can probably even set it at some time other than the past, and if you have enough of the “I know it when I see it” steampunk aesthetic, it will probably still read as steampunk.

For NormanM, and also to extend the ruminations:

—“Steampunk could be considered a retro-futuristic neo-Victorian sensibility that is being embraced by fiction, music, games, and fashion. It is ornate and vibrant, and intricate. It believes that functional items can and should be beautiful.”

http://theclockworkcentury.com/?p=165

—“Specifically, steampunk involves an era or world where steam power is still widely used—usually the 19th century and often Victorian era Britain—that incorporates prominent elements of either science fiction or fantasy. Works of steampunk often feature anachronistic technology or futuristic innovations as Victorians may have envisioned them; in other words, based on a Victorian perspective on fashion, culture, architectural style, art, etc. This technology may include such fictional machines as those found in the works of H. G. Wells and Jules Verne or real technologies like the computer but developed earlier in an alternate history.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steampunk

—“A subgenre of speculative science fiction set in an anachronistic 19th century society.”

http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/steampunk

—“a genre of science fiction set in Victorian times when steam was the main source of machine power.”

http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/steampunk

Some definitions do include steam explicitly, such as:

—“Steampunk – Victorian Science Fiction that has dark & ominous tones, often where technology is an enslaving force and the main characters are fighting against the oppressive establishment. Cyberpunk with steam technology.”

http://home.dejazzd.com/broadsword/Rivets_N_Steam/RS_Glossary_Page_1.html

But even with this definition, other considerations either supercede or parallel the presence of steam technology.

This sort of broadening is necessary to explore the potential of the subgenre.

This is just such an awesome post.

I think it’s easy to get hung up in labels and definitions, and the impulse to bust up Steampunk and repurpose it and go in different directions is part of what keeps a type of fiction healthy. Yes, it’s true that definitions become more and more difficult at a certain point–but that’s great! A definition doesn’t exist to be static. It exists as a signpost to get you somewhere, not to stand still. I mean, the whole point is cross-pollination and using renovation and smashing things as a way of getting someplace new. I gotta say, a lot of this stuff is what’s energizing me and keeping me young and prolonging my personal transition over to Old Fart (t-minus five years and counting). I think we’re on the cusp of the kind of reinvention and rejuvenation in genre generally that we haven’t seen since the early aughts (and then that was in a somewhat different context).

Cheers,

JeffV

Amal, darling, you must stop writing about your stories in such a way that I feel compelled to purchase the collections they are in, it’s simply unfair!

That being said, I think your point about the genre is entirely correct. I think the “steam” in SP is more a description of a time period and an ethos than about the use or generation of steam. After all, the Damascus you are describing (I assume) is connected to the broader world by neither sailing ships nor diesel powered ships, but rather by steamships (and possibly airships – I don’t know, I haven’t read the story). More generally, the changes which are happening in the world around your Damascus of the mid to late 19th century (long, short, or otherwise – an entirely different topic) are driven by steam powered industry, and the attitudes of the people in and around your story are affected by the reality of steam powered industry – mass production, increased urbanization, and all the myriad other things which typify the mid to late 19th century.

Oh, this is such a big topic, and I look forward to discussing it with you at length at a later date.

*adds anthology to buying list*

Fantastic post! I’ve often considered the possibilities of the Middle East as a setting for steampunk, considering that for much of history they were leagues ahead of Europe in terms of science and math. Your Damascus sounds gorgeous.

@Norman–have to disagree on “Steampunk without steam is just punk.” I’ve read multiple steampunk stories, in SP anthologies and elsewhere, in which the only mention of steam was the teakettle boiling. 75% of the cool gadgets that show up in SP are actually clockwork (I’m afraid I do not make a distinction between steampunk and clockpunk; those hairs don’t need splitting.) and what steam-powered machinery there is tends to be exactly the sorts of things we have today, but with a vague idea of “steam” plastered on. Steampunk is a series of retrofuturistic ideas more than it is a strict adherence to a certain area of technology. I’d classify a show like Firefly as steampunk, even though there’s no steam; the pastiche of technologies and themes of freedom and rebellion say “steampunk” to me far more than a token pair of goggles.

I agree on the wor “ethos” being underused in relation of the question “what is steampunk, what defines it”.

As you allready pointed out, steampunk isn’t about steam, it’s not even about a specific aesthetic… it’s about a spirit, about the question “what would mankind have been if..”.

In the case of steampunk I belive the question is “what would have been of mankind if we would have relied on mechanics and the woldwiew that comes with it, instead of electronics”.

It can sound unimportant, but it isn’t. When you concieve the world (human world, cultural world) from the mechanics, you get a world where speed isn’t everything. You are not obsessed with instant communications, you revalue the notion of the travell, spending time discovering, working on something in order to make it functional… In a world of “mechanics-driven-ethos” there’s no internet, there’s no cellphone, there’s no supersonic jet, but there’s the adventure of moving from one place to another being forced to stop every now and then, you get a world where you cannot know everything and everyplace, so there’s plenty of stuff to discover. You get a place where there’s no “globalization” (as we know it)… simply because you still have the blessing of a relative isolation. your culture HAS to develop it’s own solutions, or at least is forced to adapt foreign stuff to your reallity, because nothing is instantaneous. You will end up with cultures fascinated with “new” technologies and cultures where the clash of tradition and innovation will be evident and even violent.

Oh… it’s a world of so manny unexplred stuff, that reducing steampunk to a bunch of cool gadgets, a certain century or a single restricted aesthetic paradigm (ie: victorian England), is spitting in the face of creativity.

Excelento post. It’s allways nice to see people questioning instead of just following the masses.

I absolutely agree, one-hundred-percent. We don’t need to define everything!

If I try to analyze what makes a story “steampunk” in its most general appliacation, it’s the same as science fiction – the suspension of disbelief. But while modern SF has to suspend the disbelief of a modern reader, steampunk is supposed to suspend the disbelief of a victorian reader. Steam itself is not mandatory; something recognizable as “science” to a 19th century reader is. In other words, Steampunk should read like a scientific romance written in the 19th century. So, would a person from the 19th century believe your jem-cutting-based dream machine is credible in the same way they would buy into the concept of a brass-and-ivory time machine or a moon cannon?

By the way, my favorite non-victorian Steampunk novel is Pasquale’s Angel, which takes place in Rennaisance Itlay, with Leonardo Da Vinci as the usherer of the steam age. Instead of pushing 20th century inventions back into the 19th, it pushes 19th century inventions into the 16th, to great affact. If sterampunk was invented in the 19th century, this is probably what it would have looked like.

Oh wait, make it second favorite. There’s this novel about an electric sub (see? no steam!) captained by this indian guy, who is also anti-imperialist to the bone. And Londeon doesn’t feture in that book at all. Seems like those victorians were more open-minded about stemapunk that us moderns…

A fantastic post, Amal. Thanks.

This also gives us the terms of clockpunk, dieselpunk, stonepunk (Flintstones!), aetherpunk (my personal favorite subsubusubgenre)… Steampunk is already well beyond the steam. I see this not just in what I read, but in the outfits of my fellow costumers, devices we build and the stories we all consume.

I do feel you make a great point about the nigh omnipresent Victorianism – I admit to delighting in my fob watch and homburg. It does get rather ridiculous in the Australian heat. I’ll be looking out for your stories, I do love seeing the genre being pushed in new (to me) areas. I don’t think we need to take the Atomizer 9000 to the genre, though, we build it by being part of it.

I very, very much like the notion of “retrofuturism.” I can see such a subgenre being as explosive and endlessly recreative as “interstitialism.”

The thing about “steampunk,” though, is that the word itself is so evocative. It’s fun to say, fun to write. Is there a more fun way to say “retrofuturism,” I wonder?

Hmm, this article very much brought to mind a short essay by Catherynne Valente about steam punk. I don’t really have an opinion here, but the relevence drove me to post a link.

http://www.catherynnemvalente.com/essays/blowing_off_steam/

What a marvelous and beautiful article!

Of course your solar-powered 19th century Damascus in which water is far too precious a fluid to waste on making steam is Steampunk! May all the Gods protect us from Steampunk fundamentalists — of all things! — insisting on a literal reading of a term that was simply a play on the term “Cyberpunk.”

I wouldn’t say you’re out to destroy steampunk, but fashioning better goggles the more clearly to see.

Yes! Brilliant piece. The more narrowly and strictly people insist on following a particular genre, the more restrictive it is to creativity, intellectual curiosity and exploration, and can eventually be the death of itself. Corsets, while fashionable, were not healthy.

Oh my gosh, your comments are wonderful! Thank you so much for them, everyone — I’m going to have quite the time trying to answer these properly.

wandering-dreamer (and everyone who’s expressed interest in the anthology): yes, the story is appearing in Steam-Powered, which, as it happens, just opened up to pre-orders yesterday! It’ll ship in late January, and pre-ordering by November 3 gets you nifty postcards with teasing story-bits on. You can see more of the rest of the contents in this post of JoSelle Vanderhooft’s; I highly, highly recommend Nora Jemisin’s “The Effluent Engine” for a story you can read straightaway.

Joe in Florida: Wow, I had no idea there was acrimony between the Clarke/Douglas camps! That’s fascinating. The binary that’s characterised my growing into fandom has been a divide between Fantasy and SF, so it’s awesome to learn of other tensions around what SF should or shouldn’t be.

ubxs113: Thank you! I’d say there’s nothing particularly wrong with posing, so long as you’re okay with someone saying “you do realise that the pith helmet you’re wearing sends a message to lots of people that isn’t O HAI I IS COOL XPLORER, right?”

JohnnyEponymous: But is the end of Victorian thought the beginning of the 20th century? And does the end of thought begin with the publication of a book, or a few years later when the book’s effect has rippled outwards? All lines in the sand, re-drawn each time the tide heads out. :)

eruditeogre: Thank you! And I like the idea of the British expulsed from India 40 years earlier — best of luck with that story.

Mine is indeed “To Follow the Waves,” and I hope you enjoy it when it comes out. :) And totally agreed about Tor.com doing a brilliant job of this — I’m honoured to be part of it.

NormanM: I generally prefer that terms err on the side of expansion and inclusiveness rather than otherwise, myself — and as eruditeogre points out, the definitions are varied as it is. I think, too, that “for the purposes of communication” can have a great deal of scope: I might use the term differently if I’m recommending a film to someone than if I’m recommending a book, describing an aesthetic, what have you. The word “steampunk” needn’t exist in a vacuum where only one meaning is possible; it can be changed and inflected depending on context, I think. As JeffV says downthread, “It exists as a signpost to get you somewhere, not to stand still,” and I can’t really put it better than that.

JeffV: Thank you so much! I very much doubt your Old Fartitude is at T-minus 5 years. I hereby proclaim your progress towards Old Fartitude to partake of the Centuries’ progress towards their end, which is to say, apprehendable only in retrospect several years past an arbitrary mark. :) Also,

“I think we’re on the cusp of the kind of reinvention and rejuvenation in genre generally that we haven’t seen since the early aughts” — YES. It’s entirely possible that this was happening earlier and I wasn’t aware of it, being more consumer than producer, but I’m amazed at the the in-depth discussions that take place on panels at cons, and then the way those discussions spill onto the internet, and vice versa. There are so many more vectors of communication to take into account, and it can only enrich things.

MTimonin: *buffs nails, looking decidedly unapologetic*

I’d love to talk about this in person sometime, Historian Friend! I wish you could’ve been at the panel on Politics of Steampunk at Wiscon this year — we covered so much ground.

omega-n: Hooray! I do hope you enjoy it!

kaosnokamisama: I take your point about mechanisation vs. electronics; I think a big part of the aesthetic is being able to see all the moving parts of technology, not being at several removes from it as we now are. The laptop on which I’m typing this may as well be powered by nano-sized gerbils for all the understanding I have of its innards.

Messmer: Thank you!

Michael_GR: Hmm. I look at this:

In other words, Steampunk should read like a scientific romance written in the 19th century.

And wonder, WHERE in the 19th century? Both temporally and geographically, it’s not a monolith, and someone might believe a given thing in Syria but not in India. That said,

So, would a person from the 19th century believe your gem-cutting-based dream machine is credible in the same way they would buy into the concept of a brass-and-ivory time machine or a moon cannon?

If we’re talking about Victorian England, I think so. One of the things I deeply love about that time and place is that so many of the innovations that helped usher in our modernity were invented by self-identified Occultists and Spiritualists; the minds figuring out radio waves were the same minds imagining it used to communicate with the dead.

Terri: Thank you so much!

Professor Von Explaino: Thanks! “Clockpunk” is just so fun to say.

Grey Walker: I like it too, but have no notion of how to make it less of a mouthful!

Alexander K: I adore that post of Cat’s — Liz Gorinsky quoted from it as a jumping-off point for discussion on the Politics of Steampunk panel I was on this past Wiscon. It’s excellent, and I’m honoured to have brought it to mind!

Metallion: Thank you so much for reading!

LynnH: Oh man, that is an EXCELLENT analogy — steampunk as corseted by too-narrow-definitions, which lead to distortion of its ribs, laboured breathing, an inability to move, and a predisposition to fainting and vapors! Certainly very unhealthy.

Almamothar:

Now that you mention the fact that in mechanics you “see” what’s inside, to see how things work, another core point of steampunk world comes to my mind… In a world of mechanization (especially if you are not obsessed with niniaturization) there’s lots of space fot “do it yourself”.

It’s easier to invent, repair and/or customize in a world of mechanics, since the basics of mechanics are closer to everyday human experience, than those of electronics. You don’t have to be a specialist to build a simple machine (our world is full of DIY people who seek simple solution to their everyday problems).

I belive that’s a great point in steampunk. It’s a world where everyone has the chance to make stuff, to create stuff and to come up with clever solutions. Of ourse there are speciallists in steampunk (mechanics and engineers, for example are classics), but that won’t keep other archetypes from inventing, repairing or, at least understanding how stuff works.

Eheh. Hi everybody! I’m the editor in question who just found that this post went up today instead of, well, later. I was going to post a link to where you can get this anthology, but Amal took care of that for me. (Sorry for not being signed in; I can’t at present.)

I wholeheartedly agree with everything Amal has written here, and look forward to reading, and hopefully editing and writing, more steampunk that falls into more of this category.

Win x 10,000.

I’ve long felt that what steampunk needs is an increased recognition that Victorian England, for all its frantic self-obsession and arrogance, was dependent on a web of economic and political ties stretching to every corner of the world: Victorian London couldn’t exist without Hong Kong, Singapore, Calcutta, Bombay and on and on. Including that isn’t diluting the clockwork; it’s enriching it. You don’t need to give up on steampunk to embrace the subaltern: there are plenty there in the source material. There are an undeniable excess of them in the source material.

What a great piece – loved it!

Heresiarch: Your comment x 10,000. Thank you — you put it beautifully.

Katherine: Thank you so much!

This rant reminds me of a similar rant by Charlie Stross.

Robert Trout: His is indeed a mighty rant.

Ack, I missed these!

AsheSaoirse: Your series sounds cool, and I wish you luck with that!

Rachel Manija Brown: I can’t wait to read your story. I think Steampunk is definitely recognisable by a certain aesthetic — one that isn’t bounded by the 19C, as evidenced by the 10C astrolabe seen in this post that I’m sure could make it into many a Steampunky Adventure — but I’d like it to do MORE than that, ultimately. But I don’t disagree that knowing-when-seeing is a big component of SP today.

Whither thou goest, Amal El-Mohtar, so will I follow, bustle erect, goggles agleam, a dream underfoot and one in hand, shaped by knives of your making.

Next stop, Damascus!

I agree in general, although I don’t want it to be called “steampunk” because that’s a rotten term.

Unfortunately, it’s the one people will end up using.

-The Gneech

@amalmohtar

Thankee sai!

Yes! Just adding my voice to those saying how much this is needed. People get sooo hung up on the steam, of which there is plenty! Now the punk I say, we need more of that.

A very provocative interpretation of the steampunk genre. After the your first inflamatory statement I being to see your point and I feel I must agree. Steampunk has to be more than steam apparatus and Victorian England. It is the thoughts, ideas and impulses of mechanical, political and individual change and liberation that the steam age unleashed. The machinery may be the background or setting for a story however, it is still a background. The important factor is how the characters relate to their society and its challenges or changes.

Well done, I will ponder how this concept effects my attempts at a steampunk novel.

Thanks

Claire: lookit you, forcing me to acknowledge the pertness of your bustle!

The Gneech: may I ask why you think it’s a rotten term?

Jake: Thank you so much!

Greg: I’d go so far as to say that the steam age didn’t “unleash” those thoughts, ideas, and impulses; it provoked them, but you don’t need 2 and 2 to make 4, you know? 1 and 3, 1 and 2 and 1, 1 and 1 and 1 and 1… So long as those thoughts, ideas, and impulses are observable, you can locate “steampunk” just about anywhere.

As someone who absolutely adores the idea of western steampunk, and abhors rigity in what can be so much more, I wholeheartedly agree.

At first I thought this was one of the few anti-steam rants I’ve run across, but, I was pleasantly surprised.

Some tried to tell me that when I saw things like Bioshock as steampunk I was wrong because it wasn’t victorian and took place in the 1960s/60s. My notiosn is that like all genres of fantasy, it can be what yo uwish it to be if it fits the general setting.

kurisu7885: Have you by any chance seen this post by Monique Poirier at Beyond Victoriana? I think you may enjoy it too!

honestly, I don’t blame you. the ‘steam’ in ‘steampunk’ has, for me at least, only ever been a reference to the time period that it’s inspired by, rather than a limiting factor. it’s supposed to highlight that steampunk is inspired by a time filled with new ideas and technology, usually powered by steam. other than that, ‘steam’ has little to no influence on me when I do something with steampunk in mind. I more often associate beauty, science, technology, and romanticism with steampunk than I do actuall steam, and if you can get steam-powered this and that and the other thing to fit in, well good for you. but that doesn’t mean steampunk has to be steam and only steam. that’s would be like saying that all German’s are/were supporters of Hitler, or that all Americans drink instant coffee. it’s an uneducated generalization, and most of all, it’s not true.

I spent some time ruminating on this

post,I think some trends that you identified in steampunk mirror

trends in punk as a musical form. with the original bands (The Clash

especially, uniting elements of reggae with rockabilly and pub rock)

there is a creativity, an energy, which is breaking new territories,

experimental descriptive and adventurous. By the time you get further

down the line it becomes prescriptive. (Punk is only mohicans and

bondage trousers.)

Of course any such creation of static

prescriptive symbols causes a kickback, and spin offs as a reaction

against the symbols becoming the status quo (Bondage trousers, and

brass cogs).

I always felt the original

cyberpunk was a movement against the space opera type scifi to look

more at what other groups within society are doing, the more

character focussed, under the radar groups,, and the way that

technology could be subverted (As an archaeologist I loved that Neal

Stephenson gave his hitman character flint weapons to get through

airport metal detectors.)

I think this is what you are doing with

your exploration of the Damascus steampunk, and potentially with the

concept of mythpunk. We all flock towards pigeon holes, like doves

returning, partly to be able to identify markets to sell are work,

but these should be exploratory and experimental rather than

restricting and limiting

Great post – As a fantasy author, I truly applaud the notion that “fantasy shapes the dragon” not the other way round. I just contributed a short story to a forthcoming anthology “Steampunk Shakespeare” – a steampunky rendition of A Midsummer Nights Dream. Like the original, it’s set in Classical Athens – in a world where the Continent of Atlantis has developed steam-powered technology. While the melding of steampunk and Shakespeare seemed an instant and completely logical melding of two literary concepts to me, I’ve been surprised at the number of people who can’t wrap their minds around the notion – so much so that the volume’s editors had to put an article up on the website explaining that A) the Victorians knew and enjoyed Shakespeare and B) that Shakespearian performances in the 19th century were not necessarily set in the 19th century. In any case – thanks for making the case that there’s a whole world … a whole universe of retro-sci-fi, gaslamp, steampunk adventures just waiting to be discovered outside of Victorian London!

In an academic sense, I can appreciate your argument and I genuinely admire that you want to take a genre apart, switch out its pieces, and put it back together inside-out just to see what might happen. The world needs writers who do this because frankly, the day that fiction becomes so formulaic that each reader can write the story by reading the first page is the day that fiction becomes a dreary real world instead of the explosions of color and chaos that constitute a dreamed-of world. I myself have often thought that it’d be fun and interesting to turn established norms on their head and say that the emperor has no clothes on, just to see how the crowd reacts.

All of that said, however, there is a certain dishonesty in grabbing terms and reinventing them out of a desire to personalize them. To use a very extreme example, someone who wanted to write feminist literature without being bothered to even mention gender: the term has been appropriated to include something that is missing the most critical pieces. Thus it is with steampunk: steampunk without the critical characteristics of the genre (the replacement of modern technologies with steam-driven mechanics) is not actually steampunk. It is legitimate and it is indeed a new idea that keeps the wide world of retrofuturism vibrant and exciting but language has no meaning if you can appropriate any term you like to describe anything you want just to give it an appealing shine. It semes better to say “I want the era and look of steampunk without the steam so I dub my idea… gempunk” than to say “It’s just SO unfair that steampunk is confined to technologies that are steam-driven but I like the term so my story without steam is steampunk so there.” You’ve already crossed the boundaries; your ship has sailed off the edge of the world, you’ve stumbled into the undiscovered country, you woke up in fairyland, you’ve made something new and fresh to titilate potential fans. Why not pull up a toadstool and start a lively conversation about sealing wax with Queen Titania over a nice cup of “Drink Me”?