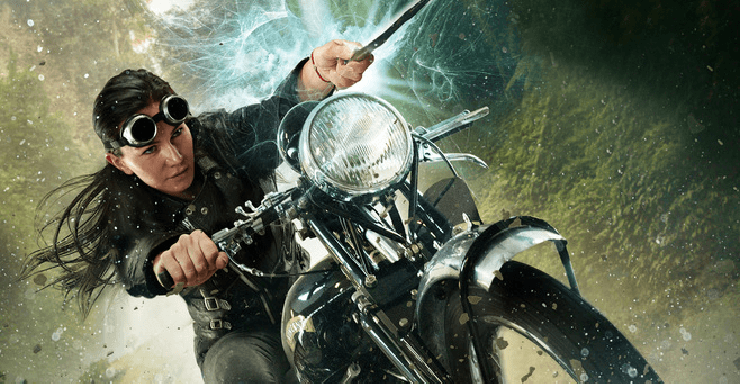

David Mack’s Dark Arts series continues as the wizards of World War II become the sorcerers of the Cold War in the globe-spanning spy-thriller The Iron Codex—available January 15th from Tor Books.

To tide you over until the book arrives, we’re thrilled to present “Hell Rode With Her,” which takes place between books one and two of the series. David Mack explains:

This novelette is a story arc that was excised from the first Dark Arts novel, The Midnight Front. It details events that befall Russian-born sorceress (aka “karcist”) Anja Kernova after she deserts from the Red Army in late 1943. This was in fact the first part of the Dark Arts series that I wrote, and Anja’s confrontation with her countrymen during the Great Patriotic War sets the stage for the series’ second book, The Iron Codex, in which Anja is the chief target of an international magickal arms race in 1954.

“Hell Rode With Her”

A Dark Arts story

February 1944

There was no hero’s welcome for Anja Kernova.

One heavy step after another, she defied the Russian winter. Half-healed wounds plagued her as she trudged through knee-deep snow that numbed her feet. After weeks of icy weather and empty roads, she had returned for the first time in over a decade to the place of her birth: the isolated village of Toporok.

Tucked against the south bank of the River Msta, the village had never been much to see. More than five hundred kilometers inland from the eastern front, Toporok was a lumber town that tolerated just enough farming to feed its handful of permanent residents.

Anja glimpsed its ramshackle houses and its patches of clear-cut woods, and she felt comforted to see little had changed in the decade she had been away. The sharp tang of smoke from dozens of chimneys perfumed the wintry twilight.

Ghosts born of her memories hid in the lengthening shadows of dusk. She had been thirteen years old the last time she had seen this place.

Will anyone recognize me now?

Many times in recent years she had felt confounded by her own reflection. The rigors of learning the Art had taken their toll on her youth, and whatever shreds of her innocence magick hadn’t stolen had now been ripped away by the Great Patriotic War.

Unfamiliar faces squinted at her through grimy windows. Her former neighbors looked at her as if she were a stranger.

I’ve been away so long. Maybe I am.

She adjusted her ruck and tugged the strap of her tool roll, which bit into her shoulder. After she had passed a dozen houses, she noticed that nearly every face she saw was female. She had spied only two exceptions: one a young boy, no more than three or four years of age; the other an old man, his hair white, his face a deep-creased map of life’s heartbreaks.

In all of the spots that Anja expected to see boys committing a day’s final mischief before dinner, her searching gaze found only empty spaces. Toporok, as small as it was, had given the Red Army its every man and boy who could hold a rifle or die to stop a German bullet.

Mournful winds whipped up snow devils between dilapidated houses. Anja pushed herself toward a destination that filled her with hope and fear.

She stopped a few paces shy of the closed door. The house looked as she had remembered it. The faded paint still the blue-gray of a late-winter sky. Behind its shuttered windows, a glow of firelight. But where once the house had been alive with music, tunes plucked by young fingers from her family’s old balalaika, now there was only the cry of the wind.

Buy the Book

The Iron Codex

Intimidated by the house’s silence, Anja stood frozen in front of its door. Once she would have pushed it open and charged inside without a thought. Now, dancing shadows hinted at a blaze inside the hearth where long ago she had soothed her cold hands, but her guilty conscience warned her she would find no comfort within these walls.

But I don’t know where else to go.

Dread paralyzed her. If she left without knocking, no one would ever know she had been here. She would be free to vanish into obscurity and anonymity. There would be no questions to answer, no lies to tell. All she had to do was turn away and keep walking. The night would swallow her as it always had. As it always would.

An insatiable emptiness inside her made her step forward, lift her hand, and rap her knuckles against the weathered wood and blistered paint. Then she waited.

From the other side came the slow, muffled scrape of a body in motion. Tired steps on a wooden floor. The knob creaked as it turned, and the hinges shrilled in protest as the door was cracked open. Anxious eyes peered out at Anja. Impatience added an edge to her mother’s rasp.

“What do you want?”

“Mama? It’s me.… Anja.”

Galina Kernova opened the door wide enough for Anja to see her face. It felt to Anja as if she were peering at a mirror from the future. She and her mother shared the same pale cast, raven hair, gray eyes, and elegantly arched eyebrows. They might have been twins but for their difference in age and the irregular, Y-shaped scar that dominated the left side of Anja’s face.

Her mother scowled. “What do you want?”

“Can I come in?”

“No.” She started to shut the door.

Anja struggled to keep it open. “Please.”

“You let Piotr die.” Galina pushed her away and spat at her. “You’re dead to me.”

She slammed the door. Heavy clacks of turning locks resounded through the thick wood. In all the years since her mother had cast her out to fend for herself, Anja had never felt so alone.

There was little point in seeking shelter from anyone else in the village. No doubt her mother’s bile had long since poisoned them all against her. Why did I come here? Why did I think she would forgive me? That any of them would?

Mired in loneliness, she could think of only one place to go, and of only one soul in Toporok who would receive her without judgment.

Bereft of hope or purpose, Anja left home for the second and last time.

* * *

Piotr’s headstone stood entombed in ice. Anja kneeled in the snow and chipped with the pommel of her knife at the marker’s frozen shell until her younger brother’s name was visible. She sheathed the blade and pulled off one of her gloves. Her fingers traced the rough-hewn letters of his name. You didn’t deserve this, little brother.

She couldn’t silence her memory’s litany of regrets.

If only we hadn’t blundered into the middle of a wizards’ duel.

If only Adair, dying at Kein’s hand, hadn’t pleaded with his eyes.

If only you hadn’t tried to interfere.

She remembered watching Kein’s magick cut Piotr in half—just as she recalled taking up the rifle her brother dropped, and putting three rounds through Kein’s back. It should have been enough to kill the bastard, but thanks to magick he’d escaped with his life.

Thus it had fallen to Anja, with Adair’s somber aid, to take home the two halves of her brother’s corpse. It was a failure for which her mother had never forgiven her, and never would.

She felt ashamed, not for the unwitting role she had played in Piotr’s death, but for indulging in the sentimental folly of thinking he could hear her lament. He is dead and gone. It is too late to ask his forgiveness. All the regret in the world cannot change that.

Her memory of that night remained vivid and terrible. It hadn’t mattered to Galina that Anja hadn’t done the deed, or that Adair had vouched for the truth of her account, or that she herself had been wounded. All that Anja’s mother had cared about, then or now, was that her only son was dead, and Anja was the one she had chosen to blame.

Anja rested her head against the stone and let the night settle over her. After all she had done and suffered, she had hoped for a warmer homecoming than this. She had nearly died of her wounds in Kharkov. As soon as she had been strong enough to walk again, some inchoate need inside her had turned her path homeward.

Where else can I go?

The war had engulfed the globe, leaving few civilized places untouched. In the neutral countries, a Russian woman alone would attract suspicion as a possible spy; she’d find no peace there. She could only hope the Red Army considered her missing in action rather than AWOL. And even if she knew where to find Adair, she couldn’t go back to him now, not after the cruel way she had abandoned him and Cade.

A man’s voice interrupted her brooding: “You should not have come here.”

She lifted her head from Piotr’s gravestone and looked over her shoulder. A young man towered above her. He had hard eyes, a shark’s smile, and the hunger-chiseled features that had become endemic to the Russian people since the start of the war. His Soviet military overcoat bore a major’s rank insignia. A trio of Red Army lieutenants stood a few yards behind him.

A hundred meters behind the lieutenants, a company of Red Army soldiers with horses and a pair of large artillery pieces were bivouacked in a clearing just outside the village.

The four officers’ uniforms were immaculate and sported straight, razor-sharp creases. Their boots were so well polished that they reflected the light of the crescent moon. It was obvious to Anja that they weren’t combat commanders—these men were Soviet political officers, the ideological enforcers of Premier Stalin.

Anja stood slowly and faced them. “This is my home.”

“Not anymore. There’s nothing left for you here.” The major pulled off one fur-lined glove and offered his hand to Anja. “Major Dmitri Tarpov.”

She ignored his outstretched palm. “What do you want, Comrade Major?”

“I just want to speak with you.”

Suspicion and fear sped her pulse. “You don’t even know me.”

“Quite the contrary. I know you better than your mother does.” He tilted his head toward the village. “Come in from the cold, Comrade Kernova. We have much to talk about.”

* * *

Tarpov and his men escorted Anja inside a small house on the edge of the village. She looked around the bare kitchen. “I thought this house belonged to the widow Galiyeva.”

“Don’t be absurd. The house belongs to the state.”

He closed the door behind Anja. She fixed him with the same glare she would use to cow a demon. “But you do know Karolina Galiyeva lives here.”

“Not at the moment. As loyal citizens, she and others in the village are letting us borrow their homes.” Tarpov shrugged off his overcoat and folded its shoulders together. She noticed an odd insignia stitched on his shirt’s left shoulder: an Enochian warding glyph, one that shielded its wearer from angels and demons. He draped his topcoat over the back of a chair. “Have a seat.”

Despite the light from the kerosene lamp on the table, Anja saw no warmth in Tarpov’s features. Even bathed in the flame’s amber glow, his sky-blue eyes and pale cast made him look like a man of ice and steel.

She unfastened the buttons of her down-filled field jacket, slipped it off, and dressed the back of her chair with it. Tarpov sat down, so she did the same.

He beckoned one of his lieutenants, then directed him with a lift of his square chin toward a nearby hutch. “Bring us those glasses and that bottle.” Tarpov set his elbows on the table and looked over his steepled fingers at Anja. The silence between them was filled by the snaps and cracklings of the fire inside the wood-burning stove, and by the low clinks of the shot glasses against the vodka bottle as they were carried to the table.

Anja stole a sly look at the lieutenant’s shoulder as he set down the bottle and glasses. His uniform bore the same warding glyph she had spied on Tarpov’s shoulder.

Tarpov picked up the bottle, twisted off the cap, and poured two shots. He pushed one across the table to Anja. She picked it up, and he lifted his. “To the glory of Mother Russia.”

She acknowledged the toast with a nod and downed the sharply medicinal, homemade vodka in one gulp. She slammed down the shot glass. “What do you want, Comrade Major?”

“As I said, to talk.” He placed his empty glass on the table. “I’ve been looking for you for quite some time.”

“You find female companionship that hard to come by?”

He refilled both glasses and used his to nudge Anja’s back toward her. “It takes time for news from the front to reach the Kremlin. It wasn’t until October of forty-three that I first heard the rumors of the ‘angel’ who’d ‘worked miracles’ during the Battle of Stalingrad.”

She feigned amusement. “Miracles?”

“A female soldier who could heal the wounded. Command the city’s legions of vermin to attack the Nazis. Turn herself into a bird and go places no one else dared, to gather vital intelligence on the enemy’s movements. What would you call these feats, if not miracles?”

“Fairy tales.”

Tarpov sipped his vodka, nursing it this time. “I know better.” He set the glass on the table and traced its rim with the tip of his forefinger. “I have access to classified files, comrade. I know you were part of a top-secret Allied group known as The Midnight Front.” He looked into her eyes and took her measure. “You’re a black magician—a trained sorceress.”

“We prefer to be called karcists.”

“I don’t care what you call yourselves. One can’t argue with results, and your old friends have crushed the Thule Society in Europe.”

Anja fought to keep her face a cipher even as she exulted at Tarpov’s news. She had feared her desertion of Adair and Cade might have jeopardized their chances of bringing down the Nazis’ army of amateur magicians. It was a relief to know they had prevailed against the dabblers despite having been outnumbered more than a hundredfold.

She downed her second shot of vodka and met Tarpov’s gaze as she put down the empty glass. “So you know who I am. What do you want, Comrade Major?”

A smug, lop-sided smile failed to soften his sinister aspect. “A demonstration.”

“Excuse me?” Anger warmed her face and narrowed her eyes.

Her protest seemed to amuse him. “Show me some magick.”

“I don’t do parlor tricks, Comrade Major. And I don’t take requests.”

He cocked an eyebrow in mockery. “Lost your feel for it?”

“What would you know of the Art?” A disparaging nod at his uniform. “Aside from how to copy warding glyphs out of a book.”

“You like them? Every man in my unit wears one. Can’t be too careful, after all.” He steered back toward the topic. “Just show me how to do something simple. Something easy.”

“There’s no such thing as ‘easy’ in real magick. Every act of true magick, from the smallest to the grandest, relies on the summoning and control of demons.”

“I’m aware of that.”

“Then you should know that tasking a demon requires rigorous instructions, to make sure it doesn’t pervert your intentions through willful misinterpretation. As for the kind of magick you want to see, that would entail a ritual known as yoking. I would have to bind a spirit to myself and compel it to let me wield its powers as if they were my own.”

Tarpov waved at the empty air. “So? Call up a devil and yoke it. I’ll wait.”

His ignorance was vexing. “A proper conjuring takes hours of preparation. Even one mistake would be fatal. And yoking demons to your soul is a miserable experience. The more spirits you yoke, and the longer you hold them, the more painful it gets.”

“No doubt.”

“You speak as if from experience, but you have no idea. When you’re tied to a demon, you want to scratch your own skin off. Yoke too many and you’ll have nosebleeds and a headache that never ends.” She traced the rim of her empty glass with her finger. “I’ve spent too long dragging demons in my shadow, Comrade Major. To be frank, I’m exhausted.”

“I’m sure you are. How many kilometers have you walked since you deserted? Eight hundred? Nine? All in winter.” He finished his vodka. “We’re a long way from the war.”

“Where I plan to stay.”

He tsked and shook his head. “No. The Party has big plans for you.” Condescension crept into his tone. “Assuming, of course, you’re still loyal to Mother Russia.”

The question filled her with resentment. “Why wouldn’t I be?”

“You mean aside from deserting in time of war? The Party officially endorses atheism, while you practice an Art that trucks in dealings with Infernal spirits. I’m sure you can see the conundrum that presents for the Central Committee—to say nothing of Premier Stalin.”

“I don’t make the rules of magick. I just follow them.”

“No one’s asking you to do otherwise. But the Party would feel more… let’s say comfortable… availing itself of your talents if you were willing to reaffirm your loyalty.”

Her mood shifted from resentful to enraged. “You’re demanding an oath from me?” She sprang to her feet and knocked her chair backward onto the floor with a bang. Tarpov’s lieutenants charged into the room but halted as he raised his hand. Anja lifted her sweater and her shirt to exhibit the ragged scars that crisscrossed her torso. She pointed them out, one by one. “Stalingrad. Kharkov. Kursk. These are the oaths I’ve sworn to Mother Russia, each one signed in blood.” She dropped her shirt, leaned over the table, and gave her contempt free rein. “I won’t have my loyalty questioned by the likes of you, Comrade Major.”

He sighed. “You disappoint me, Comrade Kernova. Look beyond the next battle and try to see the shape of the future.”

She crossed her arms. “If your vision is so clear, why don’t you describe it to me?”

“The tide of the war is turning. By summer the Americans will lead the Allies back into western Europe. The Nazis’ days are numbered. But after Berlin falls, the next great struggle will be for the future of Europe, and then for the rest of the world. America’s capitalist barons are just fascists by another name. Unless we stop them, they will oppress and exploit the workers of the world. If we are to rebuild the earth as a workers’ paradise, Russia must assert its dominance on the global stage, wherever and whenever possible.”

Confusion creased Anja’s brow. “How does that concern me?”

Tarpov refilled their glasses. “Despite the Party’s misgivings about the very existence of the Art, Premier Stalin sees it as a useful weapon in the battle for global domination—one over which he would prefer Russia held a monopoly.” He picked up his glass and slid the other across the table to Anja. “He wants you to kill your former master, Adair, and his last remaining apprentice, the American, Cade Martin.”

A chill of dread filled Anja’s soul. Standing mute in front of Tarpov’s searching stare, she let go of the lies she had told herself about why she had abandoned her friends. She hadn’t done it to serve Russia or to restore her family’s honor. She had run away because she had felt betrayed by Adair’s demand that she sacrifice the life of someone she had cared about to save the life of Cade, who had taken her place as Adair’s favorite pupil. In spite of her lingering resentment toward them, however, she still considered them her friends. Now, Premier Stalin wanted her to betray and murder the only two people in the world who still mattered to her.

She flung her vodka into Tarpov’s face.

He winced. “Arrest her!”

Two of the lieutenants seized her arms and legs. A third drew his sidearm and jammed it into the small of her back. “What should we do with her, Comrade Major?”

“Lock her in that empty shed out back.” When the officer with the drawn pistol reached down to retrieve Anja’s coat, Tarpov added, “Leave it. I want her to feel the cold.”

The junior officers dragged Anja toward the house’s back door. She looked back in silent horror and saw Tarpov confiscate her leather tool roll and her rucksack, in which she kept her grimoire of demonic contracts—both of which she needed in order to arm herself with magick. Deprived of them, she would be at his mercy.

Tarpov shot her a mirthless smile as she was taken out the door into the potentially lethal cold. “I’ll give you some time to contemplate the error of your decision, Comrade Kernova. Perhaps when we speak again, you’ll be more willing to see things my way.”

Hate filled her heart, and she seared the image of his smirk into her memory.

Don’t count on it, Comrade Major.

* * *

Fitful slumber fled like crows from a gunshot. The Cossack yanked away Anja’s moth-eaten blanket and doused her with half a bucket of ice-cold water. She gasped and cried out, then hugged her rope-bound wrists against her torso to subdue her violent shivering.

It was night again. Anja had lost track of time since being confined to the shed. All she had known for certain had been daylight or darkness. Winter wind and pale sunlight spilled through the same gaps in the walls’ weather-beaten planks.

Her gut told her it had been days since she’d eaten; it had been just as long since she’d slept more than a few minutes in a row. The dilapidated shed had no stove, no hearth, nothing to fend off the brutal cold except her threadbare brown blanket, which the Cossack had delighted in taking from her at seemingly random intervals, in between doling out brief but savage beatings.

Dim light silhouetted the Cossack and grew slowly brighter as he lit a kerosene lamp. Its glow spilled over Anja as her captor turned and hung the lamp from a hook in the middle of the shed’s low ceiling. Then he pulled back the hood of his gray fur coat, revealing his unkempt mane of ash-and-charcoal hair and his wild black bramble of a beard.

The door opened, admitting a howl of wind and Major Tarpov. He closed the door and looked at Anja. His breath wreathed him in pale vapor as he spoke. “You’re awake. Good.” He gestured toward the Cossack. “You haven’t been properly introduced to my interrogator.”

She dipped her chin like a charging bull. “Don’t you mean torturer?”

Tarpov ignored her accusation. “Comrade Kernova, this is Ivan Dershanko.”

“We’ve met.”

Tarpov’s steps scraped on the frozen dirt floor as he moved closer. He squatted in front of Anja and caressed her bruised face with his gloved hand. “That was merely prelude, comrade.”

“Prelude? To what?”

“I suggest you cooperate and obviate the need to find out.”

“I’d spit in your face but my mouth is too dry.”

That earned a low chortle from the major. “I respect your spirit. But why prolong the inevitable? All I ask is that you obey a lawful order.”

“I’d sooner cut my own throat.”

Dershanko drew his knife. Tarpov grabbed the Cossack’s wrist and shook his head. The bearded man sheathed his blade as the major asked Anja, “May I suggest an alternative?”

“You want me to cut your throat? Gladly.”

Tarpov stood tall in front of Anja—and kicked her, hard. His perfectly polished boot slammed into her gut and her chest, over and over again. She kept her hands up to defend her head and her face. As she fell in a fetal curl to the dirt floor, he landed more crushing blows to her ribs. By the time he stopped, she couldn’t breathe, and she couldn’t form a cogent thought through the pulsing agony that filled her body.

After several seconds, the pain became merely awful. She blinked away the spots in her vision and watched Tarpov wipe her blood from his boots with a soft cloth. He smiled at her. “Attention to detail is so important, wouldn’t you agree?” He finished and tucked the cloth into a front pocket of his overcoat. “I have a confession: I haven’t been entirely honest with you.”

She replied through clenched teeth. “Imagine my surprise.”

“Asking you to kill your old master was merely a pretext, an excuse to observe magick in practice. My interest in the Goetic Art extends beyond curiosity, but the Party’s overzealous purging of the libraries has left a dearth of primary sources on the subject.”

“A shame.”

“Quite. I’ve tracked down stray pages of the Grimorium Verum, and the first part of Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonium, but the Clavicula Salomonis has proved elusive.”

Anja drew a slow breath through gritted teeth. “It usually does.”

“But if an experienced witch—begging your pardon, karcist—were to instruct me on the particulars of conjuration and control—”

“No.”

“Don’t be so rash, comrade. Teach us to summon and yoke spirits, and you can go free.”

“Us?”

“Me and my lieutenants.”

Suspicion darkened Anja’s thoughts. She recalled what Tarpov had said about every man in his unit wearing a warding glyph on his uniform, and she realized she had seen the practice before. “You’re forming your own Thule Society.”

“Yes, the Red Star. It’s a brotherhood at the moment, but we’d welcome a sister with your talents.” Excitement lifted his voice. “Join us, and you and I can lead it together.”

It was so absurd, she had to laugh through her pain. “Are you insane?” Her humor turned bitter. “You really think Premier Stalin would let amateurs like you wield power like this?”

“I don’t plan to give him a say in the matter.”

She pushed herself to a sitting position against the wall. “You’re talking about a coup.”

“More of a regime change. Magick will be my route to power”—he seized her chin in his gloved hand—“and you are going to show me the map.”

Anja recoiled from his grasp. “And if I don’t?”

“I’ll kill your mother.”

She sneered at his threat. “The woman who disowned me when I was thirteen? Who just slammed a door in my face? Why should I care what happens to her?”

A knowing gleam lurked in Tarpov’s stare. “True, your mother despises you. Anyone can see that.” He loomed over her, his countenance turning to one of pure menace. “But if she meant nothing to you, you would not have come back to Toporok.”

Anja seethed. Tarpov was right, and it was obvious he knew it.

He’s smarter than I expected.

She drew a deep breath and focused her thoughts. Her captors held every advantage over her except one: They had no conception of the rigorous mental discipline Anja had mastered in order to become a karcist. Tarpov’s and Dershanko’s preferred weapons for psychological warfare were cold, hunger, sleep deprivation, and sadistic violence. Anja’s weapon of first and last resort was her own mind.

She purged herself of emotion and aimed her fierce stare at Tarpov.

“I will watch you die, Comrade Major.”

His derisive snort made it clear he considered her threat an empty one. “Not tonight, you won’t.” He picked up her blanket and threw it at her. “Spend another day in here. I’ll come back when you’re ready to be reasonable.” Dershanko lifted the kerosene lamp from the ceiling hook and followed Tarpov out of the shed. From the other side of the door came the heavy thud of an oaken crossbar being lowered into place, locking Anja inside.

She tucked her legs against her chest and huddled under her tattered square meter of woolen cloth. Staring into the darkness, she set her mind to a singular purpose:

Escape.

* * *

The wind rose and fell with banshee howls that shook the shed’s rickety walls and wormed into Anja’s nightmares like the groans of Baba Yaga, the child-devouring hag whose legend taught every Russian child to fear the dark. Anja hid beneath her too-thin shroud, but the cold’s subtle fingers always found a way inside.

Footfalls crunched in the snow outside the shed. Pushing herself to overcome her fatigue and focus her senses, Anja distinguished two cadences in the pattern of steps. Even before the door opened, she knew who to expect. She heard its crossbar being lifted and removed. Her empty stomach growled as she took a breath to steel herself for the confrontation to come.

The door opened with a gritty creak of rusted hinges. A mighty gust of midnight cold pushed in ahead of Tarpov and Dershanko and blew Anja’s blanket to the shed’s far corner. She clutched her knees and tried in vain to halt her chattering teeth as her captors entered.

Dershanko looked like a wild man in his patchwork rawhide pants and hooded fur coat. The shaggy, thick-bearded Cossack hung a lit kerosene lamp from the hook on the low ceiling.

Tarpov’s uniform was immaculate, and his face showed no hint of stubble. He toted Anja’s leather tool roll over his left shoulder. In his right hand he carried her ruck.

He set down the tool roll and leaned it against the wall next to the door. Then he opened the ruck and pulled out her grimoire, a thick tome of virgin parchment pages bound inside pale calf-skin covers emblazoned with a demonic sigil and tied shut with a black silken cord.

“Let’s try this again, Comrade.” He clutched the weighty book in one hand by its bound edge and admired it. “Teach me how to use your book of spells, and I’ll let you leave here alive and unharmed.”

She tried not to cackle with derision but couldn’t help herself. Tarpov’s mood soured while he waited for her to regain her composure. After several seconds, her cynical amusement abated. “A grimoire is not a book of spells, Comrade Major. It’s a book of contracts—agreements I’ve made with spirits subordinate to my Infernal patron.”

He furrowed his brow at the codex. “Then where are your spells?”

“The only spell that matters is the one for conjuring. Anyone with a modicum of intelligence can do that. But to wield true magick? That requires forging pacts with the powers of Hell. And while many dream of striking deals with the Devil, few have the nerve to pledge their eternal souls in a compact signed with their own blood.”

Her warning didn’t faze Tarpov. “I could make such a bargain with ease.”

“Could you?”

He shrugged at the grimoire. “I’m an atheist. I don’t believe in souls. I’d be happy to give up something I consider imaginary in exchange for nearly limitless power.”

She harbored a grudging respect for his certainty. “All right. If you want to possess the secrets of creation, take them. Everything you need to know about conjuring is in that book.”

Tarpov’s suspicion was evident in his stare. He kept his eyes fixed upon Anja while his fingers tugged and pulled at the knot of the silken cord. The harder he pulled, the tighter the cord hugged the magickal tome. He switched the book to his other hand and tried again. To his frustration, the knot refused to be undone. He glared at Anja. “How do I open it?”

A cruel smirk. “Really, Comrade Major? You think yourself wise enough to command the greatest powers in creation—but you can’t undo a simple knot?”

His face flushed with anger until he calmed himself. He extended his hand to Dershanko. “Your knife.” The Cossack handed his blade to the major, who slipped the weapon’s edge between the book’s cover and the silken thread. “If it was good enough for Alexander—”

With a quick, upward pull he severed the black cord.

The sigil on the cover erupted in a jet of living smoke that enveloped Tarpov—and then the licks of black vapor became a violent rush of scorpions and spiders.

Tarpov screamed, dropped the knife, and stumbled sideways. He swatted madly at the hundreds of attacking arthropods as they skittered up his limbs and across his face, stinging and biting as they went—and then he tripped over his own feet and fell against the wall.

Dershanko stood dumbfounded by the grisly spectacle for half a second before he turned his back on Anja to try to help Tarpov.

She sprang to her feet. Though her wrists were bound, her hands were free enough to seize the base of the kerosene lamp and lift it off its ceiling hook. She shattered the lamp’s glass chimney against the Cossack’s forehead. Spilled fuel coated his face, and the burning wick ignited his bramble-beard and tousled mane into a bonfire. His horrified screams drowned out Tarpov’s, and the shed filled with greasy black smoke from Dershanko’s incineration.

Anja dived to the dirt floor and grabbed the dropped knife. She plunged its blade halfway into the rock-solid ground, then set her wrists’ bindings against its cutting edge. Within seconds she sawed through the rope and freed her hands.

The major writhed on the floor in the corner, fighting to save himself from the stinging curse he’d unleashed by cutting the grimoire’s cord. Anja stuffed the book back into her ruck and slung the bundle over her right shoulder. She plucked the Cossack’s knife from the floor with her right hand and grabbed her tool roll in her left, on her way out the door into a night whose bitter wind cut like a razor.

She had barely dashed three steps toward freedom when she saw an infantryman charge toward her, no doubt drawn by Tarpov and Dershanko’s panicked cries. The soldier stumbled to a halt and fumbled for a fraction of second as he tried to chamber a round into his rifle.

Anja threw the knife. It sank into the sentry’s throat and knocked him onto his back.

He gagged on his own blood as Anja set upon him. She handled him without ceremony, rolling him onto his belly so she could remove his coat. The horror of impending death dimmed his eyes as she took his scarf, gloves, and rifle. By the time she had donned the stolen overcoat and shouldered the rifle, the young man lay dead at her feet.

Anja had no time for mercy or regret. She plucked her knife from his throat.

And she ran.

* * *

Tarpov howled in pain as he slapped away the spiders swarming his head. The prickling of hairy legs on his throat and neck was punctuated by red-hot bursts of pain as one bite and sting after another assailed his bare skin. Their attack felt incessant—then it ended as he flung the last of the crawling horrors from his head and crushed it with his gloved fist.

He grabbed his hat and scrambled to his feet. The shed was filled with horrid black smoke and the reek of scorched meat, spent kerosene, and half-boiled blood—all of it emanating from the charred corpse of Dershanko, which lay smoldering in the back corner.

As Tarpov lifted his hat to put it back on, a scorpion tumbled out of it and landed at his feet. He stomped on it and relished its wet crunch beneath his boot.

All at once he was struck by the sum of his pain. His face, neck, and throat felt as if they had been lit on fire, and his balance deserted him. Excruciating pressure filled his skull and pressed against the backs of his eyeballs. His mouth went dry, and his tongue started to swell.

…have to get outside—need to get help…

He staggered toward the door and all but fell through it, quitting the smoke-filled shed. Nausea overcame him, and he vomited as he pitched face-first into the snow. He landed beside the bloody remains of a young soldier who had been standing sentry nearby.

Tarpov rolled onto his back and drew his TT-33 semiautomatic from its holster. Fighting the pain that was spreading through his body, he raised the weapon and fired three shots into the air. Then his strength failed, and the pistol’s weight pulled his hand back down into the snow.

Minutes that felt like forever dragged past. At last, he heard the commotion of people running toward him, and he forced his swollen eyes to crack open.

Two of his lieutenants, Kokarev and Ledovskoy, stood at his feet. The senior lieutenant, Nikulin, kneeled beside him and asked, “Comrade Major? Are you hurt?”

“Are you blind? Get a doctor!”

Nikulin was perplexed. “For what, sir? Have you been hit?”

The burning sensation on Tarpov’s face and neck became unbearable. “Look at my face, Yuri!”

The senior lieutenant looked at his peers, who shrugged. With obvious reluctance, Nikulin looked back at Tarpov. “I see nothing wrong, Comrade Major.”

“What are you—?” Before he finished the question, Nikulin fished a small steel hand mirror from his overcoat and turned it toward Tarpov.

The major’s reflection confirmed the lieutenant’s report. There were no wounds or marks on Tarpov’s face. No bites or stings, not even a scratch. Confronted by visible proof, his pain vanished—but his newfound fury left him quaking.

The witch tricked me! Made me think I was dying—made a fool of me!

“Help me up,” Tarpov snapped. His lieutenants took hold of his forearms and hoisted him to his feet. He brushed the snow and dirt from his trousers and overcoat. “The prisoner has escaped.” He turned to face his men as he continued. “Send out search parties to—”

In the distance, limned by pale moonlight, he spied a lone figure running through the village’s cemetery, toward a thick stand of tall trees on the far side. “There she is! In the graveyard!” He pointed his pistol to fire at her, then lowered it when he realized she was out of range. “Kokarev! Send everyone you can after the girl! Now!” Kokarev sprinted back to the camp to rouse the men. Tarpov pointed at Ledovskoy. “You! Wake the gunners! Tell them to load the A-19s and target that forest.” Ledovskoy raced back to camp behind Kokarev.

Nikulin sidled up to Tarpov. “Artillery, Comrade Major? For one girl?”

Tarpov’s eyes tracked the retreating Anja Kernova through the distant graveyard. “She had her chance to stand with us. Now let her see what it means to be against us.”

* * *

Every breath Anja drew felt like fire. Running through shin-deep snow left her muscles cramped and trembling. She weaved between headstones and fought to stay upright as dizziness struck her in waves. Her only hope of escape was to reach the dark stand of trees on the far side of the cemetery. It was so close, she could smell the pine… .

Rifle shots echoed in the night. Bright ricochets bit chunks of rough stone from the grave markers on either side of her. Machine gun fire churned the snow to her right. She ducked by reflex and plunged to the ground. More bullets tore across the gravestones closest to her.

Can’t stay here. Have to keep moving. Got to keep my head down.

There was no time to worry about pain; her whole body hurt, but at least she was alive. She slogged forward in a deep crouch. The cracks of rifles and the chatter of machine guns filled the night—but behind the clamor, Anja heard the faint, distant cry of a train’s whistle.

A shot caromed off a headstone and stung her face with rocky shrapnel. She dodged behind the rough-hewn marker and pulled her stolen rifle off her shoulder to shoot back at her pursuers. As soon as she felt the resistance in the rifle’s bolt lever, she knew its previous owner hadn’t been taught to cut his gun oil with gasoline to keep it from freezing shut. Until it was warmed and cleaned, the rifle would be all but useless. She cast it aside and resumed her run toward the woods. It was just as well, she decided; she was faster without it.

She passed the last row of headstones and sprinted as hard as she could despite the snow resisting her strides. Nearly a dozen meters of open ground lay between her and the shelter of the trees. Speed and shadow were her only chances now. The bridge over the frozen River Msta was half a kilometer to the north. To get out of Toporok with her life, Anja had to reach the other side of the river alive—and ahead of her pursuers.

Gunfire kicked up snow and dirt all around her. She zigzagged and hunched forward to protect her head. A close shot screamed past her ear. The fearsome buzzing of machine-gun fire resumed, and chunks of wood and bark were torn from the trees beside Anja as she hurtled to cover inside the dense, dark woods.

* * *

Tarpov’s patience dwindled with each passing moment. “Where is she now?”

He and Nikulin stood between the A-19s as enlisted men in noise-blocking earmuffs loaded the 122mm cannons, which had been hastily pivoted by the horses to target the woods. The lieutenant lowered his binoculars and frowned. “I’ve lost her in the trees.”

“Let me see.” Tarpov took the binoculars from Nikulin and peered into the night. A hundred meters away, a platoon of his riflemen and machine gunners charged into the woods. A second platoon was flanking east to circumnavigate the trees at a double-quick march over open ground. Tarpov lowered the field glasses and turned to the artillery team’s sergeant. “Fire.”

The sergeant and his men looked baffled by the order. “Comrade Major?”

He repeated his command, his tenor grave. “Target the woods and fire at will.”

“Comrade Major, our own men are in there!”

The girl was escaping, and Tarpov had little reason to think his riflemen would catch the fleeing witch unless something impeded her retreat. He drew his TT-33 and pressed its icy muzzle to the sergeant’s temple. “Comrade Yakunin! I gave you an order! Open fire, and keep firing, until that witch is dead or that forest is gone!”

Yakunin swallowed hard and answered in a small voice. “Yes, Comrade Major.” He turned and barked at the enlisted gunners, “Fire!”

Tarpov and Nikulin pressed their gloved hands over their ears. Then the night sky turned to flame, and the guns shook the earth as if with God’s own thunder.

* * *

Anja ran through the woods, her memory of its paths guiding her steps even in near-perfect darkness. Wild shots zinged past her and bit into old trees, but she kept moving and never slowed down, no matter how close the ricochets came.

Twin booms of artillery brought her to a halt. She had spent over a year on the front line; she knew what was coming. She dived face-down in the snow and covered her head.

Deafening explosions blasted through the treetops. Heavy limbs and shattered trunks rained down, all of them burning. Smoke laced with gunpowder filled the woods.

Fifteen seconds, Anja told herself. A competent A-19 crew could fire three to four rounds per minute. Tarpov’s gunnery teams had made the mistake of firing in tandem instead of staggering their shots. That left her fifteen seconds to run before the next salvo dropped.

She sprang to her feet and ran through the maze of swift-spreading flames.

More rifle shots cracked behind her—until the brutal clattering of machine guns drowned them out. Behind the gunfire rose the hue of angry male voices.

Another double boom heralded the next fusillade. Anja hit the deck.

The next two shells detonated in the trees a few dozen meters to either side of her. Huge craters erupted into being. The blasts hurled uprooted trees like burning javelins that spread fire as they fell. Once these woods had been Anja’s redoubt and refuge. It was the only part of Toporok that still felt like home to her. Now it was going up in flames.

She got up and ran with all the strength she could summon. Again came the din of shouted commands at her back, followed by the sharp reports of Mosin-Nagant rifles.

Two strokes of thunder were followed by the fearsome whine of falling ordnance. The edge of the woods was in sight, and Anja took her chances on the move.

Half a dozen soldiers charged after her, their rifles raised and ready to fire—until a tempest of fire hurled them like leaves on a gale. Severed heads and limbs flew in all directions. The shock wave launched Anja backward against a tree trunk. She fell to the ground, her senses dazed, her limbs rubbery. Flames sped toward her. She let herself fall and buried her face in the snow as the fire cloud rolled above her.

Cold and wet, the snow beneath Anja’s face shocked her back into action. She lifted her head. The woods had been transformed into a hellscape. There was no sign of the troops who had chased her inside. She turned her head and spied a hint of clouds glowing blue-gray with reflected moonlight. The edge of the woods was near.

Two more thumps of incoming fire boomed in the distance.

Anja used a tree trunk to pull herself upright. Explosions deep inside the forest sent tremors through the cold, hard ground as she lurched down the icy slope of the river’s south bank. Encouraged by the rising cry of an approaching locomotive’s whistle, she staggered across the next obstacle on her journey to escape—the Msta.

The river was narrow and its surface was frozen solid, as it often was in deep winter. From her first step on the ice, Anja was sure it was thick enough to support her weight—but it also was blanketed in a fresh layer of snow, which would make for treacherous footing during her rushed crossing. Recalling a trick from her youth, she kept her feet as flat as possible to reduce slippage. It slowed her pace but kept her steady as she forded the frozen river in the shadow of the double-arched railroad bridge, which towered above her.

She was halfway to the north bank when gunshots peppered the ice. She took cover on the west side of the bridge’s center pylon, whose patchwork of multicolored stone barked with ricochets. Anja peeked around the pylon’s edge. She glimpsed the shadowy forms of soldiers who had gone around the woods in an attempt to cut her off. The squad was more than a hundred and fifty meters away, by her reckoning. Between them and the bridge, her beloved woods burned, belching out black smoke and blistering heat.

If I had a working rifle, I could pick them off before they—

Screams of incoming artillery rounds cut her wishing short. Both shells hit the frozen river and churned huge swaths of ice into foam. Great plumes of water roared into the air. Fractures in the ice radiated up and down the river from both impact points, filling the night with low cracks that sounded to Anja like the breaking of a giant’s bones.

Fissures split the ice at her feet. Anja feared the Msta was about to swallow her whole. Then the wind shifted—and drew a curtain of smoke from the burning woods across the river.

She abandoned caution and ran. The ice crunched and sagged beneath her with every step. Gunshots cut divots in the snow around her, but she knew the soldiers were shooting blind.

Above and behind her, a train crossed the stone-and-steel bridge with a clattering rumble that drowned out the gunfire. Anja had the river’s north bank in sight as her foot plunged through a splintered patch of ice. Icy water stung her calf like a hundred needles.

She freed her foot after less than a second, but each running step she took up the riverbank sent jolts up her leg and stabbing pains through her bruised ribs. Bullets ripped into the snow and chased her to the top of the slope, to the tracks at the north end of the bridge.

Anja looked south into the headlight of the oncoming train. For safety’s sake it had slowed to cross the narrow bridge, but now its engine was all but on top of her. Her muscles felt stiff and spent, but she needed a few more seconds of cover—the kind of protection only the train could provide. She dived over the tracks and felt the locomotive’s harbinger of displaced air push her the last few centimeters to safety on the far side.

Rifle shots pinged off the train’s boxcars as Anja rolled into a low crouch, her ribs aching. She needed to act quickly, before the train’s last car left the bridge, clearing the way for it to accelerate back to full speed on its northward journey. She unslung her ruck and tool roll and jogged alongside the train. Pacing a boxcar with an open door, she hurled her gear inside. Then she forced herself to sprint and dive up and inside the boxcar. Her chest slammed against its floor’s edge, and she clawed with gloved fingers at its planks for a handhold.

Whatever you do, don’t let go, she commanded herself. Climb. Climb!

Her back and shoulders ached, and her biceps and triceps burned with the effort of pulling herself over the edge. For several seconds she dangled half in and half out as track ties blurred past below her. Then she found a grip and pulled herself the rest of the way in.

Toporok and the Msta were a kilometer behind Anja by the time she huddled into a forward corner of the empty boxcar, which rocked like a cradle on the uneven tracks. She made a tent of her stolen overcoat to block out the cold, and let the ceaseless roaring of the wind and the rhythmic clacking of the train’s wheels lull her into a deep and much-needed sleep.

* * *

Tarpov watched Nikulin unfold a map of the area and point at the north end of the railroad bridge that crossed the Msta. “They lost her here,” the young lieutenant said. He traced the path of the tracks with his forefinger. “If she’s on the train, she’s a dozen kilometers away by now.” He tapped the name of the small village on the other side of the river. “But if she continued on foot, she’s probably hiding somewhere in Malinovets.”

Tarpov looked up at the tower of white smoke rising from the ravaged woods. “We could search every house in Malinovets in under an hour, and she knows it.” The sting of failure worsened his sour mood. “No. She’s on the train.”

Nikulin unfolded more of the map to follow the tracks northward. “The horses are rested. We can send six men across the river here, where the ice is solid, and have them follow the loggers’ trail out to where it meets the main road, a few kilometers southeast of Eligovo.”

The major shook his head. “It’s too far. They’ll never catch the train. Not that it matters. We have no way of knowing where the girl might hop off.” He gathered up the map and folded it. “Tell the men to break camp and get ready to move out.”

“Sir?”

“We’re heading back to Moscow.”

“What about our dead?”

Tarpov handed the folded map to Nikulin. “Leave them for the wolves.” He walked back toward the house he had commandeered as his temporary quarters.

The lieutenant followed him. “What about the girl, Comrade Major?”

“Let her run. The Kremlin awaits us, Yuri. And it will be ours, with or without her help.”

* * *

The train shuddered to a halt with a harsh metallic shriek and a loud hydraulic gasp. Groggy and cold, Anja pulled down the top of her frost-covered coat and squinted into the predawn light. Snow-mantled trees slid past the boxcar’s open doors, and a rural village encircled by tents and flimsy buildings drifted into view.

Wherever this is, it’ll do. She put the overcoat back on and buttoned it up to the scarf around her neck. Then she gathered her ruck and tool roll and hopped off the train as it slowed to a stop with a long, dwindling whine.

The woods between the tracks and the village were shrouded in fog. Guided by the hazy glow of sunrise, she trudged through the snow until she found herself in the middle of a jerry-built collection of tents and scrap-wood huts. Bedraggled masses of gaunt women, emaciated children, and withered old men stood in an uneven queue, which led inside a tent from whose stove pipe issued a steady stream of gray smoke.

Anja fell in behind the last person in line, an old woman whose nearly translucent skin was pulled taut over her skull. She nudged the woman’s elbow. “Excuse me, is this—?”

“The chow line? What else. New here, girl?”

“I just arrived, yes.”

The old woman’s demeanor turned suspicious. “Got a bowl?”

“Yes.”

“Best have it ready. Chow dogs won’t spare any.” She produced a small wooden bowl from under her filthy double layer of wet shawls. “Have to bring our own.”

No one talked, or joked, or so much as smiled in the line. After a few minutes, another dozen people had gathered behind Anja, who had moved several meters closer to the tent. She cast a wary look at the sallow, sunken-eyed old man standing behind her. “Can you tell me where we are? What this town is, I mean.”

“Budogoshch,” he muttered through crooked, yellow teeth. He regarded the camp with a weary, cynical frown. “Or Kirishi-in-exile. Whichever you prefer.”

She nodded and faced front. The German Army had occupied Kirishi for close to two years. The previous October, the Red Army had finally ousted the Nazis from the city—but had leveled it in the process.

These must be the city’s survivors. That realization gave Anja hope. If this refugee camp was like those she had seen during her time with the Red Army, it would be a confused mess at best. More likely, it would be a pit of utter chaos, especially in deep winter. She could not have asked for a better place to hide while preparing to make her next move.

Her turn at the chow table came. She left with half a bowl of lukewarm root-vegetable soup, two pieces of hard bread, and a small hunk of sharp cheese. She put the bread and the cheese in the soup as she walked away in search of a place to eat. Recalling her time in Stalingrad, she knew the cheese would improve the soup’s flavor, and that both it and the bread would be easier to chew once soaked through with starchy broth.

She followed some refugees inside a broken-down old stable. Its stalls had been turned into shelters. Each housed nearly a dozen people, who huddled in jealous knots around small, religiously maintained fires. Most of the stalls were full, but she found one with an unoccupied corner and shoehorned herself into it. Her new neighbors ignored her, which suited her.

Breakfast was bland but it quelled the angry croaks from Anja’s stomach. She sat back and collected her breath and her thoughts. For the moment she was alive and hidden. She unfurled her leather tool roll and inspected her implements of the Art. To her relief, none of them had been damaged by Tarpov’s careless handling or the rough circumstances of her escape. Had it been necessary, she could have repaired or replaced them, but that would have taken a great deal of time and effort, and it would have risked exposing her whereabouts to her enemies.

She bundled the tool roll and tied it shut. Her brazier, incense, grimoire, and candles all were safe in her ruck. There were a few more items she would need to procure for that evening’s labors, but she knew from experience where to find them and how to steal them.

The rest of the day would be her time to rest. She had a long night ahead of her.

I’ll rise when the mess hall rings the dinner bell. After that… my work begins.

* * *

The room was prepared, and Anja with it.

It was a vast open space of scorched concrete, the ground floor of what once had been the town’s fire station. The Nazis had occupied the enormous structure a few years earlier during their first invasion of the Motherland. Upon being forced into retreat by the Red Army, the Germans had gutted the station and its twenty-meter-tall watchtower—ironically, by arson.

Now it was a morgue, its walls lined with corpses stacked like cord wood. Because the ground in Budogoshch was frozen solid and wasn’t expected to thaw until late April at the earliest, the torched building’s blackened interior had been converted into a charnel house. Its reek of burnt wood, scorched metal, and rendered human fat was so potent that Anja found it hard to detect the sickly sweet incense she had lit to fumigate the space for that night’s work.

The upper floors were gone, as were the stairs to the tower, creating a cathedral-like space. The building’s windows all were boarded up, plunging its interior into pitch darkness and affording Anja some much-needed privacy for her labors. Even superstition had proved to be her ally: the refugees and locals all avoided this building for fear that it was haunted by evil spirits.

Tonight, it would be.

She checked her vestments and tools. Satisfied they were in order, she proceeded into the square, faced northwest, rested her sword flat across the tops of her shoes, lit the crucible, and set it down in front of her. Timid blue flames poked up from inside it as it touched the floor.

She drew her wand and freed it from its shroud of red silk. She draped the long crimson band around her neck and let it hang down the front of her vestments. From a pocket on the front of her alb she took a pinch of incense and cast it into the crucible. The small licks of blue light danced as the fire brightened. She coarsened her voice and said:

“Havoc. Havoc. Havoc.”

The tiny brazier spat azure sparks toward the distant ceiling. Anja thrust her wand into the sapphire blaze. Baleful, monstrous cries filled the emptiness of the station.

Over the macabre din, she shouted: “I invoke thee, great Astaroth, paladin of the Emperor Lucifer, by the power of the pact I have with thee, and by the names Adonai, El, Elohim, Zabaoth, Elion, Erethaol, Tetragrammaton, Ramael, Shaddai, and by the name Alpha and Omega, by which Daniel destroyed Bel and slew the Dragon; and by the whole hierarchy of superior intelligences, who shall constrain thee against thy will—venité, venité, submiritillor, Astaroth!”

Crimson mist that stank of sulfur, burnt hair, and rotting flesh spewed from the crucible and swirled above the circle of protection, but no answer came. My patron tests my resolve. Anja fixed her countenance in its cruelest shape and bellowed above the continuing tumult:

“I adjure thee, Astaroth, by the pact and the names, appear!” She plunged her wand into the brazier’s twisting flames. The clamor of unholy howls grew louder. Her patron had grown defiant in the many months since she had last called it forth. Luckily, the Art provided remedies for such intransigence, and Anja had no qualms about their use.

“Now I adjure thee, Put Satanachia, whom I command, send me thy messenger Astaroth, forcing thee to forsake thy hiding place, wheresoever it may be, and warning thee that if thou dost not manifest this moment, I will straightaway smite thee and all thy kind!”

She stabbed her wand once more into the flames.

A terrible stroke of thunder roared from the ceiling and rained dust upon Anja’s head and shoulders. An ominous temblor shivered the ground beneath her feet.

An answer came from the darkness, a rasp of shadow and cinders.

Stay thy rod; I am here. Disturb not my father. What dost thou demand of me?

“Hadst thou come when first I invoked thee, I should not have had cause to rouse thy father. Defy my request and I pledge my rod will return to the fire, and thou shalt feel my wrath.”

An unearthly sea-green mist snaked upward from inside the pentacle to the northeast, and a soul-chilling wind of putrid vapors swept over Anja. She tried not to breathe it in, but she couldn’t help herself. It took all her strength not to double over and retch.

As the fumes dissipated, Astaroth’s avatar coalesced. To Anja’s surprise, the demon eschewed its usual parade of false forms and manifested in its true shape. Outside the circle appeared a nude, handsome angel with flowing golden hair. Its feathered wings were tarnished with blood and ash. In its right hand it held a writhing viper. A ten-pointed crown glittered with painful brightness upon its brow. It sat astride a beast that sported a hyena’s head, a lion’s paws, a feathered torso, leathery wings, and a serpent’s tail. The monster’s every exhalation cloaked it and the demon in violet flames, and poisoned the room with a sulfurous miasma.

Astaroth stroked its huge, tumescent, coal-black penis and flashed a leering grin. Its voice was deep and full of innuendo. Nice to see you again, my dear.

“Stand by the seal.” She gestured with her wand toward the triangle. “Stand and cease your foolishness before I plunge you back into the fires whence you came. I command thee!”

The demon growled in exasperation; its erection flagged. It and its bestial steed vanished in a noxious puff and reappeared a moment later, above the restrictive bounds of the triangle. A scent of musk suffused the air, displacing the foul odors that had accompanied its arrival. Its affected geniality deteriorated into naked hostility, and its voice shrank to a human dimension. “Why hast thou summoned me? Now is neither my prescribed day nor my appointed hour.”

“I have brought thee forth because I have need of thee—the stars be damned.”

“Then speak so that I may know thy mind.”

“I need to call up and yoke all those spirits with whom I hold pacts.”

Her admission stoked his curiosity. “All of them? To what end?”

“I must smite many enemies ere the sun rises. But to do so, I require the service of all your minions who have sworn by blood and oath to obey me.”

The demon’s callous laughter filled the room. Anja jabbed her wand into the crucible, which spat gouts of blue fire as the demon roared in pain. When she pulled back the wand, the beast glowered at her. “Foolish Eve-spawn! Never hast thou yoked so many spirits at once. Thou hast harnessed at most a dozen of my kind at a time. More than that would be a burden beyond your ken. It would be as the weight of the world upon your soul.”

“I require their powers—and your aid—only for this one night. Come dawn, my work will be done, and all shall be released, discharged in peace by the terms of the Covenant.”

Astaroth was dubious. “Greater karcists have died attempting lesser feats.”

“Hence, I need your strength, great one. With thy aid, I shall have victory.”

“A single spirit would be more than equal to your foes. Haborym could—”

“The patients are warded. They can’t be sent for. I must face them directly.”

The demon struck a thoughtful pose. “How great are their numbers?”

“Nearly a hundred, all protected by the seal of Vassago.”

The spirit turned suspicious. “The service you demand is no trivial matter. To break Vassago’s seal, I risk angering my father. What wilt thou promise me in return?”

“For thee, I have in mind a special prize.” She dipped her chin and fixed the demon with her knowing stare. “One that shall give thee no end of delight.”

* * *

Winter’s keen edge slashed at Tarpov as he emerged from his tent into that desolate silence peculiar to three o’clock in the morning. Unable to sleep, he had laid awake feigning dreams, rather than demoralize his troops by pacing among them. But the confines of his tent had grown too close. He needed to be on the move, even at this godforsaken hour.

He strolled past rows of flimsy tents, inside which his men huddled for warmth. He and what remained of his company were camped on the hilly, winding country road between Okulovka and Kresttsy, a kilometer past Lake Peretna. On his orders, they had left the A-19s behind in Toporok. Freed of the burden of the artillery pieces and their cumbersome ammunition, the company had traveled forty-eight kilometers at a quick march in one day.

Something cold and wet kissed his nose. He looked up to see falling snow. Just what we didn’t need. He had hoped to make a swift return to Moscow; now he faced the grim prospect of finding himself and his men snowbound in the wilderness. We can probably make Kresttsy by midday tomorrow, he reassured himself. We’ll have to bivouac there until—

A low, steady rumbling snared his attention.

Thunder? In the middle of winter? The snow fell faster as he turned in one direction and then another, struggling to discern the sound’s origin.

A sentry’s whistle shrilled from the formation’s vanguard. Tarpov hurried forward, weaving between bleary-eyed men stirred from their tents by the alarm. He sidled up to the young sentry. “What is it, Polnikov?”

The enlisted man pointed into the distance. “A light on the road.”

“What kind of light?”

The sentry trembled. “Like fire, but it… it was… green.” His eyes widened and he pointed again. “There!”

Tarpov’s weary eyes strained to pierce the night’s snowy veil—and then he saw it, a gray mirage in the distance. Licks of emerald flame along the ground cast a spectral glow upon the galloping form of a majestic warhorse and its cloaked rider as they charged over a crest in the uneven road. Tremors shook the macadam under Tarpov’s boots, and he realized the frightful steed racing toward him was the source of the thunder.

He knew then who the rider must be, and what had to be done.

“Get up! All of you! Skirmish line! Now! Move, damn you!”

Men scrambled out of tents and bedrolls, grabbed their rifles, and mustered with shivering limbs and chattering teeth into a double-rank battle formation behind him. It took them less than a minute to assemble for combat—but by then the lone rider had arrived.

The steed was larger than any Tarpov had ever seen. Its hide was as pale as corpse flesh and taut over rippling coils of sinew. Green flames gusted from its flaring nostrils and blazed beneath its great black hooves. It champed its bridle in a fiendish grin of bloodstained teeth.

Seated on its back was the witch, a runesword in her right hand and a gnarled wand in her left. Her vengeful stare fixed upon Tarpov. “Did you really think I’d let you stage a coup with your band of dabblers? I’m many things, comrade, but above all, I’m a patriot.” She aimed her wand at him and raised her voice. “Comrades! Your major has brought this upon you. If any of you want to see the new dawn, rip the seal of Vassago from your uniform and walk away. I give you my word I will grant safe passage to every one of you who renounces the Red Star.”

Nervous murmurings and anxious glances moved among the men. Tarpov shouted over his shoulder, “Stand fast! Take aim!” His order was answered by the clattering of rifles being brought to bear and well-oiled bolts chambering 7.62mm rounds.

Anja regarded Tarpov with cold contempt. “You have to die, Comrade Major. Your men do not. Tell them to forsake their treasonous oath and let them leave here with their lives.”

Tarpov drew his TT-33, aimed at Anja, and bellowed, “Fire!”

An explosion of rifle shots split the night as all his men unloaded in unison on the witch.

The night swallowed the cannonade. A ragged, drifting cloud of gunsmoke dissipated to reveal Anja, sitting tall upon her Nightmare. It snorted green fire, which illuminated her face as she cracked a diabolical smirk. “So mote it be.”

She spurred the demonic beast and charged—and the hosts of Hell rode with her.

* * *

Cries of struggle and flight surrounded Anja as the Nightmare trampled Tarpov’s men. A lucky few who were fleet enough to escape the steed’s burning hooves met the edge of her sword; those less fortunate discovered what it meant to die by magick.

Each flourish of her wand dealt death. With an invisible fist, she broke ten men like tinder. A snap of her wrist cracked a demonic whip and unleashed hellfire. She hurled hundreds of Leraikha’s arrows into a dozen men who fell dead, skewered by the ghostly shafts.

The battle whipped past, a blur of blood and fire. Anja lurched from one kill to the next, intoxicated by the pandemonium even as the burden on her soul made her weep in grief. To bind so many fallen spirits to herself had been excruciating. In the conjuring circle, it had seemed a small price to pay for justice. Only now, awash in the bloodlust of ancient powers whose hatred had been born with the shattering of the cosmic egg, did she understand how far out of her depth she really was. Sweat drenched her hair, even in the bitter cold. Fiery pain churned in her gut. Her heart raced with the fuel of panic. Demonic voices filled her mind with fear and confusion.

On her right, two men wielding bayonets raced toward her, unaware she had been made insubstantial to the touch of metal by the favor of Eligos, whose spectral scepter she swung with a wave of her wand, scattering her attackers into the forest like petty vermin.

Another trio of infantry rushed Anja from her left. One thought summoned the aid of Marax, a demon who manifested as a bull with prodigious, upward-curving horns. It impaled the three soldiers and cast them to the road’s shoulder with a jerk of its head.

Chaos and despair drove Tarpov’s men into retreat. The handful who shed Vassago’s seal and fled, Anja let go. She saved her wrath for those who, whether out of folly or a misplaced sense of loyalty, chose to make their stand beside their doomed major.

She tugged the Nightmare’s reins and turned it back the way she had come. The last men at Tarpov’s side were his three lieutenants. Had she been in a sporting mood, she might have dismounted and challenged them to pit their sidearms against her blade. Instead, she commanded Furcifer to harry them with terrifying forks of red lightning, and she used her wand to land its cruel bolts on the three adjutants’ chests.

Their scorched remains collapsed at Tarpov’s feet.

The major stood as if paralyzed, though Anja had placed no curse upon him. She slowed her steed to an easy trot and halted it a few meters shy of the terror-struck political officer. “What’s wrong, Comrade Major? At a loss for brave words?”

He reached inside his overcoat and pulled out a small, tarnished silver crucifix. He thrust it toward Anja and the demon-steed at arm’s length, his eyes wide and his hand shaking.

Anja laughed. “Hypocrite. You say you’re an atheist, that you worship the state, but when you think the trappings of faith can save you, you cling to them like a sailor grasping at flotsam.”

Tarpov scowled. “You’re right. I have no more faith in it now than I did before.” He cast the crucifix into the bloodied snow. “But I still believe in the Soviet cause. And I sent a rider ahead to the Kremlin, to tell them what you’ve done. You’ll pay for your betrayal.”

She almost pitied him. “I command kings and princes of Hell. I’ve even looked upon the ineffable darkness of God itself. But you think I’m afraid of the Communist Party?”

He shut his eyes, fell to his knees, and bowed his head. “Kill me and be done with it.”

“Sorry, Comrade Major.” She sheathed her sword in her tool roll and tucked her wand under her belt. “I’m not going to kill you.” She dismounted, slung her tool roll across her back, and hefted her ruck over one shoulder. She stood before her confused, vanquished foe. “I have something far worse in mind.” She gestured at the snorting demon-steed behind her. “Comrade Major, meet my patron, Astaroth. He’ll be your god now.”

In a swirl of violet smoke the Nightmare transformed into the proper form of the great prince of Hell. The foul angel astride its chimeric horror smiled down at Tarpov.

Anja shed her burden of yoked spirits as she walked away into the enveloping night and falling snow. Behind her, Tarpov’s screams echoed in the arboreal wilderness. His funereal shrieks grew increasingly pathetic and faint until, at last, only the cries of the wind remained.

No one would ever know the part that Anja had played in sparing the world the horrors of the Red Star. She would get no commendations, no medals, no applause. Worse, she had no idea where to go, or what to do next. Everything that had ever given her hope felt lost to her now: the Soviet cause; her mother’s forgiveness; the soundness of her own judgment.

She wanted to believe she could make things right with Adair, but her heart was too raw to face him. How can I atone for leaving him when he needed me most? She decided the notion of redemption was folly. Is there anything left in the world worth fighting for?

Anja had seen too much, suffered too much, to believe in illusions like love and hope—yet she couldn’t bring herself to exorcise their fading light from her soul.

The road ahead was long and dark. Anja set her eyes on the future and kept walking.

The night received her with open arms, as it always had.

As it always would.

“Hell Rode With Her” copyright © 2018 by David Mack