There are a wealth of books on writing out in the world, from the good to the bad to the absolute nonsense—and a lot of them are by writers of speculative fiction. “Writers on Writing” is a short series of posts devoted to reviewing and discussing books on the craft that were written by science fiction/fantasy (and horror) authors, from Stephen King to Nancy Kress. Whether you’re a beginning writer, a seasoned pro or a fan, these nonfiction outings can be good reads.

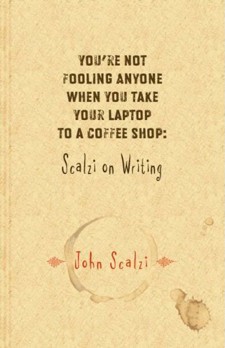

The book with the longest title in my whole pile, John Scalzi’s You’re Not Fooling Anyone When You Take Your Laptop to a Coffee Shop: Scalzi on Writing was released in 2007 by Subterranean Press. It’s a collection of columns from his blog Whatever over the course of five years that deal with writing, the writer’s life, business and pleasure. This format will be familiar to anyone who bought and enjoyed the other collection from Whatever, Your Hate Mail Will be Graded.

The immediate, obvious value of this book is that Scalzi is in no way shy about telling it like it is. The reader won’t find any flowery, romantic notions about starving artistry in this book. Instead, there are honest discussions of what working in publishing is really like, how to make money as a writer (hint: it isn’t easy and you will have to do work that doesn’t tickle your creative fancy), and how to behave, based on how Scalzi himself made it down the road to be the success he is today

And it’s pretty funny, too.

There are four sections in the book and it seems most productive to review them one at a time, as they’re rather specifically focused. The first section, “Writing Advice, or Avoiding Real Work the John Scalzi Way” is composed primarily of lists. These lists deal with what one would consider the most obvious parts of a writer’s beginning career—things like the realities of fairness: there will be worse writers than you making more money than you, and as a corollary, there will be writers much more talented than you languishing without a sale.

The best thing about this introductory section isn’t the simple “duh” things like “learn how to spell” (which does still need to be said, unfortunately) but the fact that Scalzi is a writer of many things, not just fiction, and he applies that knowledge to give advice. In fact, much of the advice in this first section is about selling articles and nonfiction to build your name and portfolio. If you want to be a professional writer, not everything you write is going to be rainbows and the Muses. Some of it is going to be serious work. That was some of the most honest and useful advice I had ever heard at the time this book was released. He also follows that up with an admonishment to never take so much on your plate that you don’t love that you run out of time for the things you do. (I will admit on a personal level that I have a problem with this. Learning to turn down paying work is a hard skill.) The section on rejection is especially compassionate and easy to understand, and will perhaps make many young writers feel better about that damned letter on their desk.

Immediately following is the second chapter, “Yo Ho, Yo Ho, A Writer’s Life for Me” which is by and large about money and being a professional writer instead of how to be a professional writer. It’s mostly anecdotal and personal. The book-deals section is far and above the handiest thing in this section, as the rest of it is made up of interesting biographical anecdotes that are amusing and fun but not hugely useful. (It is cool to know Scalzi’s relationship to books and wanting to become a writer, don’t get me wrong, but it’s like the biographical sections in Stephen King’s On Writing, which we will get to: cool stories, not advice.) It provides a nice slap of realism when it comes to how much most people are paid for their deals that is sobering for a new writer or a fan who was previously unaware how little their favorite authors really make. (Then the next post, which is a hilarious argument with Jeremy Lassen of Nightshade about the previous one on deals, shows the publisher’s half of the issue.) It’s especially interesting to note that Scalzi’s nice cozy income did not come from fiction, at least at the time of this book, but from nonfiction and corporate work.

The third section, which Scalzi calls “the catty chapter,” is a sort of “don’t do this” section that uses real writers’ terrible, usually publically embarrassing screw-ups to teach you what not to do. In principle, this is a good idea. In practice, I found myself feeling a little guilty as I laughed the schadenfreude laugh. Scalzi is certainly hilarious, and many of the subjects did deserve this sort of calling-out, and you will learn things from it—but still. Wouldn’t want it to be me in that section, you know? (In which case it has done its work, so maybe it is a great thing to include?)

The last section is specifically on science fiction, but it has applications throughout genre, as most of the articles are about things like PublishAmerica’s vanity press nastiness. The rest are about marketability of SF and why it’s not a dying genre, comparing Old Man’s War to Stross’s Accelerando and commenting on the differences. One might note that the exact same arguments about science fiction as a genre, niche versus mainstream, etc. etc. are still going on in exactly the same way five years later. That’s a little disheartening as it proves we as a fandom seem to chase our tails endlessly in a panic about what’s happening to our genre, but it’s still intriguing to read about and consider.

It’s a fun book that provides a candid perspective on making a living at writing. Not everyone will find the advice to their tastes: certainly, if you can’t stand nonfiction and would rather commit suicide than write ad copy, this is not the book for you. On the other hand, there are hundreds of books about the art and romanticism of the life of a fiction writer, darling of all imagination, but there aren’t very many that deal with the practical realities of having food to eat without a dayjob if you’re a writer.

Scalzi’s tone is generally sarcastic and treads occasionally on smarmy, but I can forgive him that, because he makes me laugh. The other note is that all of the content of this book is on Whatever, still, and you could be reading it there. There’s not much alteration between the site and the book. So, it’s a collection of posts from a blog. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, since it’s frequently helpful, but readers who are picky about that sort of thing may not be enthused.

The book is slightly outdated on things like eReaders and the digital marketplace, but some of the posts are nearly ten years old, and the landscape has changed quite a bit in the interim. It’s still worth reading but you might get a giggle over speculations about when the “literary iPod” will come about. Because it already has. As a whole, though, I would recommend perusing a copy of You’re Not Fooling Anyone […] because it provides a unique look at the writing life from the point of view of someone who is both successful and a realist.

Next: On Writing by Stephen King.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.

I do believe I need to obtain this.

Cool. I love Scalzi, I could take his advice. :) This looks like one of very few actually helpful books on writing.

Note: It seems this is a very difficult to find book. Hrm. B&N, Amazon, Borders, Ebay, none carry it so far. Will keep looking.

For those with a “literary iPod” it’s available from Webscription.net

http://www.webscription.net/p-958-youre-not-fooling-anyone-when-you-take-your-laptop-to-a-coffee-shop.aspx

@ITregillis

It’s awesome. *g*

@dianadomino

There’s a link for the ebook, thanks to O.G.N.

@O.G.N.

I sent off an email to have the link changed from the SubPress page to the ebook–thanks!

I do have to get to reading this sometime. Scalzi is crazy. The argument with Jeremy Lassen sounds great, too. When I started seeing publishers and editors talk openly about their side of the biz, it absolutely boggled my mind. It still does.

It might be worth noting that this book is hard to acquire. A quick look at the Subterranean site tells me that they are sold out. Though, I could buy a used copy on Amazon for just over $60.

If anyone has any suggestions of where to buy, let me know.

@joshkidd

The link now goes to the $6 eBook, which is considerably cheaper.

I really enjoyed both of the Whatever collections and I’m a reader only.

Will you be reviewing Judith Tarr’s new book on how to write horses as well? Considering she owns 8 Lipizzans I would say she was one of the most qualified writers to write this particular book. Writing Horses – It also started as blog posts, but on the BVC blog. And it’s only available as ebook so far.

And the BVC collective also released an ebook with general advice on writing: Brewing Fine Fiction – if you buy at the BVC site there’s even a free pdf of “Ways to trash your writing career” thrown in ^^.

@Estara: Yay, another BVC reader! :)

While I actually have gotten some very quality writing and editing work done at coffee houses and at my local library (getting out of the house really does help some folks get work done!), it sounds like I’ll get a lot out of Scalzi despite the title. One of his Whatever posts about how to make money in writing is a bookmarked entry that I refer other freelancing friends to when they’re starting out. So I’ve no doubt the collection is brimming with good advice!

@alanajoli: BVC readers, unite!

The book is definitely entertaining and thought provoking, I can say that much ^^.

Thanks for your very nicely-done review.

I’ve had this on the to-read list forever. Will have to spring for the ebook, I guess…

Cheers — Pete Tillman

—

TODAY’S BUSINESS WRITING TIP: In writing proposals to prospective clients, be sure to clearly state the benefits they will receive.

WRONG: “I sincerely believe that it is to your advantage to accept this proposal.”

RIGHT: “I have photographs of you naked with a squirrel.”

— Dave Barry (who else?)

A series of reviews on writing books on Tor? Count me in!

I see that Scazi will be one of instructors at Clarion 2011. If I don’t make it there, I’ll get the book as the next best thing.

It looks like even the e-book is no longer available on the WebScription Ebooks site. Oh well. Too bad.