As you’ve probably heard, Amazon has announced that it’s producing a show set in Middle-earth, the world created by J.R.R. Tolkien in his landmark novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. With the new series reportedly headed into production in 2019, I thought it was time to revisit the various TV and big screen takes on Tolkien’s work that have appeared—with varying quality and results—over the last forty years.

First up, Rankin/Bass’s animated version of The Hobbit, first released as a TV movie on NBC in November, 1977.

As I watched The Hobbit, for the first time since elementary school, I tried to imagine what it would have been like to see the film when it first aired on television forty-one years ago. I picture a child sitting on a lime green couch in a wood-paneled basement, wearing a Darth Vader t-shirt she got after she fell in love with Star Wars (aka A New Hope, then still simply known as “Star Wars”) when it was released in theaters a few months earlier.

Our hypothetical child would have no idea that she was glimpsing, like a vision in Galadriel’s mirror, the future of pop culture. Forty years later, now perhaps with children the same age she was when she watched The Hobbit, our heroine would find that Star Wars still reigns at the box office, the most popular show on TV features dragons, and everywhere we look, humble heroes are set against dark lords: Kylo Ren, Thanos, Grindelwald, the Night King, and even The Hobbit’s own Necromancer.

But in 1977, all of that is yet to come. The animated Hobbit is merely the first step out the door. The movie is certainly aware of its larger context. It opens with a skyward-dive toward a map of Middle-earth entire, almost like the opening credits of Game of Thrones, and ends with an ominous shot of the One Ring. But despite the gestures towards The Lord of the Rings, the film largely seems content to be an adaptation of Tolkien’s children’s adventure. It even includes the songs. All of the songs.

The film opens with the sort of “someone reading a storybook” conceit common to many Disney cartoons. We then dive down to Bag-End, which is lovingly animated, but seems to exist by itself—we see nothing of the rest of Hobbiton or the Shire. Bilbo Baggins walks outside to smoke and suddenly, the wandering wizard Gandalf appears literally out of thin air. He accosts poor Bilbo, looming over the little hobbit, more or less shrieking at him, and summoning lightning and thunder. It’s a strange greeting, and a marked departure from the banter the hobbit and wizard exchange in the book.

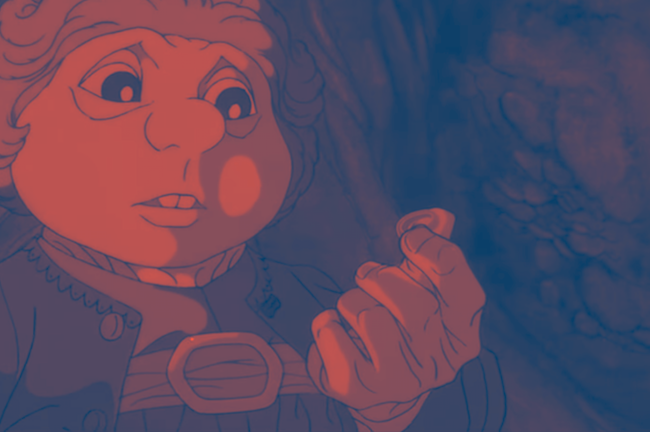

But the overriding concern of the Rankin/Bass film, doubtless due to being a TV movie for children, is to cut to the chase (metaphorically; Peter Jackson’s Hobbit movies cut to the chase literally). Gandalf doesn’t have time to shoot the shit. He needs help, and he needs it NOW. The Dwarves, looking like discarded sketches for Disney’s dwarfs in Snow White, suddenly pop up behind various rocks and trees and Gandalf gives them a quick introduction. We then cut to dinner in Bag-End as the Dwarves sing “That’s What Bilbo Baggins Hates!”, though Bilbo does not seem all that put off by their presence in his house, nor their handling of his fine china. This Bilbo is less frumpy and fusty than either his book counterpart or Martin Freeman’s portrayal in the live-action movies. He seems more naturally curious than anything—less a middle-aged man steeped in comfort but quietly longing for something more, as in the book, and more a child willing to go along with whatever the adults around him are doing.

That night Bilbo dreams of being the King of Erebor (an odd, but nice, touch that again underlines Bilbo’s naivety and curiosity) and awakens to find the Dwarves and Gandalf already saddled up and ready to go. No running to the Green Dragon for this Bilbo: Time is a-wasting! The party needs to cross the Misty Mountains, Mirkwood, and multiple commercial breaks before bedtime.

Buy the Book

The Ruin of Kings

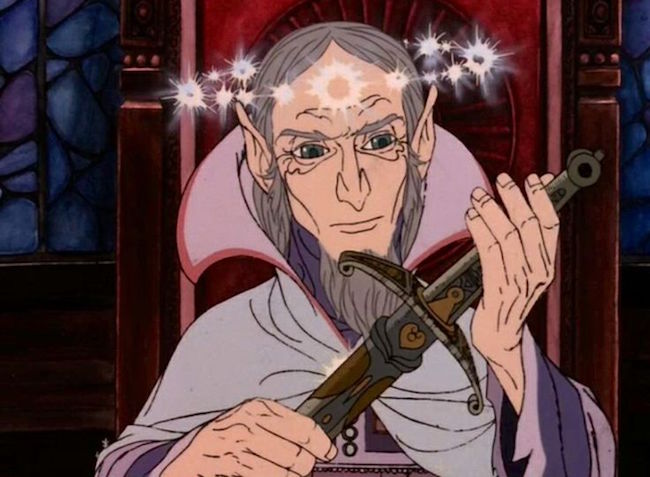

The party is captured by Fraggle Rock-ish trolls, saved by Gandalf, and then stops for dinner in Rivendell. Rankin/Bass’s Elrond sports a halo of floating stars, a high-collared cape, and a gray goatee. He looks vaguely like a vampire in a Looney Toons short who’s just hit his head. But this Elrond is still my favorite of all cinematic depictions of the Half-elven master (despite my inner nerd raging that Círdan the Shipwright is the only bearded elf). Ralph Bakshi’s Elrond looks like a bored gym teacher, and Hugo Weaving’s portrayal in the Jackson movies is too grim and dour. Rankin/Bass’s Elrond properly looks like a timeless elf of great wisdom. The star-halo in particular is beautiful and fitting, given the Elves’ love of the stars (and the fact that Elrond’s name literally means “Star-Dome”). We don’t see any other Elves at Rivendell, so it’s impossible to say if they look like Elrond or share some resemblance to the very, very different Wood-elves we meet later in the film.

Elrond reveals the moon letters on Thorin’s map, and a quick fade to black to sell shag carpeting later, Bilbo and Company are high in the Misty Mountains and seeking shelter from a storm. They rest in a cave, where Bilbo has a quick homesick flashback to the dinner at Bag-End, and then their ponies disappear and the party is captured by goblins.

I imagine our hypothetical 1977 child viewer probably had more than a few nightmares fueled by what follows. Rankin/Bass’s goblins are toad-like creatures, with gaping mouths full of teeth, plus big horns and sharp claws. They’re much more fantastical than the Orcs as Tolkien describes them—and as Jackson portrayed them in his movies—but they fit the storybook tone of the novel and the film, and also helpfully sidestep the racist aspects of the Orcs that are found in The Lord of the Rings. These goblins are pure monster through and through.

But the goblins look like hobbits compared to the slimy, frog-like horror that is the animated Gollum. Rankin/Bass’s Gollum doesn’t look like he could ever have been a hobbit. He truly looks like the ancient subterranean creature Tolkien originally meant him to be when he first wrote The Hobbit. And he’s terrifying: He has sharp claws, a disturbingly hairy back, green skin, and huge, blind-looking eyes. He also looks like he might snap and devour Bilbo at any moment.

(Funnily enough, I jotted down “reminds me of a Ghibli character” in my notes during the Gollum scene. And it turns out I wasn’t far from the truth—the 1977 Hobbit was animated by a Japanese studio called TopCraft, which was transformed into Studio Ghibli a few years later. I like to think a bit of Gollum made it into Spirited Away’s No-Face two decades later).

The Gollum scene is genuinely tense and frightening, though Bilbo again seems to take it in stride, as he also does the discovery of a magic ring that lets him disappear and escape Gollum’s clutches. The ring makes a very ‘70s-TV “vrawp!” sound when Bilbo puts it on and vanishes, and I like to imagine Sauron built that feature in for funsies: Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul, Ash nazg thrakatulûk agh burzum-ishi krimpatul. Vrawp!

Bilbo reunites with Gandalf and the Dwarves, and then the company is rescued from wolf-riding goblins by the Eagles. The only major omission from the novel occurs here, as Beorn is nowhere to be found. Which is a shame, because Beorn is a grumpy literal bear of a man who loves ponies, and he should feature in every Tolkien adaptation. Beorn appears only briefly in The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, and my only specific hope for the Amazon series is that Beorn plays a substantial role, because Beorn is awesome.

But alas, Bilbo and Co. don’t meet a single were-bear, and immediately trek into Mirkwood, sans Gandalf, where they are attacked by giant spiders. The spiders are wonderfully horrible, with mouths of sharp teeth and lips (I can’t stop thinking about spider lips) and big fluffy antenna like moths have. Also, whenever one dies the camera becomes a spinning spider-POV of multiple eyes. It’s odd, but the film goes to great lengths to avoid showing anyone actually being slashed or stabbed with a sword—even spiders.

Bilbo rescues the Dwarves but they’re soon captured by the Wood-elves, and here comes the movie’s greatest departure from the text—not in story, but in design. The Wood-elves look nothing like the elves in every other adaptation of Tolkien. Hell, they don’t even look remotely like Elrond from earlier in the same movie (presumably, Elrond took after his human grandfather). They look like Troll dolls that have been left out in the rain too long, and a little like Yzma fromThe Emperor’s New Groove. They have gray skin, pug faces, and blond hair. It’s frankly bizarre, but it did make me want a version of Jackson’s movies where Orlando Bloom plays Legolas in heavy makeup to look like a live-action version of Rankin/Bass’s Wood-elves.

The Elves may look weird, but the plot is the same. After escaping the Wood-elves’ hall by barrel, Bilbo and the Dwarves arrive at the Mannish settlement of Lake-town. There they meet the warrior Bard, who sports an extremely 1970s mustache and a killer pair of legs. I will refer to him as Bard Reynolds (RIP, Bandit) from now on.

There’s a beautiful shot of the Lonely Mountain looming in the background over Lake-town, a reminder of how close—for good and for ill—it is. In fact, the background paintings throughout the movie are gorgeous and seem to consciously adapt the look of Tolkien’s own drawings and paintings of Middle-earth, underscoring the storybook feel of the movie.

Against the advice of Bard Reynolds, Bilbo and the Dwarves head to the Lonely Mountain, where they open the secret door and Bilbo finally gets around to that burgling he was hired for. Except, of course, there’s one little problem: the dragon.

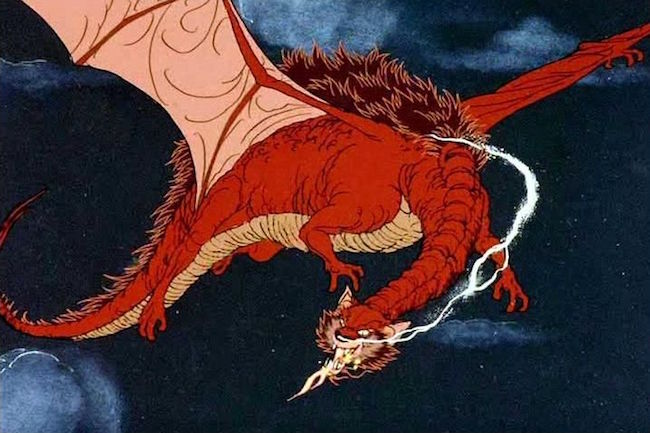

Smaug is probably the most famous, or infamous, instance of character-design in this movie. He has a distinctly feline look, with whiskers, cat-eyes, and a lush mane. He reminded me, again, of Ghibli animation, especially the canine-esque dragon form of Haku in Spirited Away. It’s nothing like our usual idea of what Western dragons look like, but it also works really well. After all, Smaug is an intelligent, deadly, greedy predator who likes laying around all day. He’s a very cat-like dragon, is what I’m saying.

What’s more, Tolkien clearly didn’t care for cats, as they are always associated with evil in his legendarium. There are the spy-cats of the Black Númenorean Queen Berúthiel, and the fact that the earliest incarnation/prototype of Sauron was a giant cat (a depiction that survives in the Eye of Sauron explicitly being described as looking like a cat’s eye). Making Smaug into a cat-dragon is brilliant. Not only does it fit the character’s personality and Tolkien’s world, but it immediately conveys the particular menace of Smaug: Bilbo (who has a slightly hamster-like look himself) is a mouse walking into a tiger’s cave.

Bilbo barely escapes, even with his magic ring, though he’s luckily accompanied by a thrush who spies Smaug’s weakness—a missing belly scale. When Smaug swoops down to burn Lake-town, the thrush informs Bard Reynolds, who sticks in arrow in Smaug’s belly. Smaug dies, but his death throes lay waste to most of Lake-town.

Back at the Lonely Mountain, Thorin has finally come into his kingdom, but like most new governments, he soon finds he has a lot of debt. Bard Reynolds and the men of Lake-town want money to rebuild their town, and they’re backed by the weird gray Elves of Mirkwood. Thorin wants to fight back, and gets mad at Bilbo not for stealing the Arkenstone (which, like Beorn, doesn’t make it into the movie) but because Bilbo doesn’t want to fight.

Thankfully, Gandalf manages to pop up out of thin air again, just in time to point out to this potential Battle of Three Armies that a fourth army is on its way: the goblins are coming. The Dwarves, Elves, and Men join together, though Bilbo takes off his armor and decides to sit this one out. Perhaps he knew that the production didn’t have the budget to animate a big battle and that the whole thing would just look like a bunch of dots bouncing around, anyway.

All is nearly lost until the Eagles show up. The book never quite describes how the Eagles fight—Bilbo gets knocked out right after they arrive—but the animated movie depicts it: the Eagles just pick up goblins and wolves and drop them out of the sky. It’s actually disturbing, as you see dozens of Eagles just casually picking up goblins and wargs and throwing them to their deaths. It reminded me of the helicopter bombardment in Apocalypse Now, and I wonder how much the disillusionment with the Vietnam War (and Tolkien’s own experience in World War I) played a role in how this battle was depicted.

We also get a view of the battlefield in the aftermath, and it’s littered with the dead bodies of men, Elves, Dwarves, goblins, and wolves. There’s no glory here, no proud triumph. It couldn’t be further from the action-spectacular of Peter Jackson’s Battle of the Five Armies, or the climax of Return of the King when Aragorn bids the “Men of the West” to fight against the armies of the East. Here, there’s just relief and grim reckoning for the survivors.

Bilbo is reconciled with a dying Thorin, then heads home with a small portion of his treasure. Given that his Hobbit-hole at Bag-End seems to exist in pure isolation, it’s not surprising that it hasn’t been seized and auctioned off by the Sackville-Bagginses as in the novel.

Instead, we end with Bilbo reading a book—a Red Book—that turns out to be his own book, There and Back Again. The narrator promises that this is just “the beginning” and the camera closes on a shot of the One Ring in a glass case on Bilbo’s mantle.

And indeed, the next year would see the release of an animated The Lord of the Rings, but by Ralph Bakshi, not Rankin/Bass. It wouldn’t be until 1980 that Rankin/Bass would return to TV with a Tolkien cartoon, Return of the King, which is perhaps the oddest duck in the whole Tolkien film catalogue, being a sort-of sequel to both their own The Hobbit and Bakshi’s Rings.

Despite being a TV movie, Rankin/Bass’s The Hobbit has held its own in pop culture. It’s a staple of elementary school Literature Arts movie days, and it’s likely been producing Gollum-themed nightmares in children for four solid decades (and still going strong!). And given the muddle that is the 2012-2014 Hobbit trilogy, Rankin/Bass’s take looks better and better every day. Its idiosyncratic character designs are truly unique, even if the Wood-elves look like Orcs. Also, the songs are pretty catchy…

Oh, tra-la-la-lally

Here down in the valley, ha! ha!

Originally published September 2018. Follow Austin’s tour of other animated Tolkien films here.

Austin Gilkeson formerly served as The Toast‘s Tolkien Correspondent, and his writing has also appeared at Catapult and Cast of Wonders. He lives outside Chicago with his wife and son.

I haven’t seen the Rankin/Bass Hobbit since, at the latest, the last time it aired on NBC the 70s. That would have been in black and white, as my family wouldn’t upgrade to color TV for several years yet. I have far less vivid memoires of the film itself than of the accompanying audio LP/illustrated storybook version, which I received for Christmas and must have listened to, and read along with, scores of times before the vinyl finally wore out. I was also fond of copying its pictures of goblins, trolls and Smaug.

While I suspect the Rankin/Bass version hasn’t dated very well, it’s GOT to be better than Peter Jackson’s abomination.

Unfortunately, the DVD copy–the one I got, anyway–somehow doesn’t have Smaug’s awesome roars, which made the cheap speakers on my old record player shake. (I, too, wore out an LP version.) We watch it pretty regularly at my house anyway. I wish the corporate culture that allowed for expanded editions to be released after the TV/theatrical cut had existed back then, because I would’ve loved to see big, cheerful Beorn and the Beornings, and so forth. It’s really a lovely little movie.

Lack of Beorn notwithstanding, this is, to my mind, the second best Tolkien movie, with only Jackson’s first LOTR movie beating it out.

Thanks for the really good article. As one of those kids that saw this in the ’70s I can say it was amazing and you’re right, I had no idea what was to come. It is certainly the best Tolkien adaptation after PJ’s LOTR.

I had the ’45 record with picture book and listened to it over and over. To this day, when I want to thank a host my instinct is to say, “My dear Elrond, your hospitality is magnificent, the food, the wine, the stories, the music…” I just can’t match John Huston’s voice, though I hear it in my head.

Somehow I’ve ended up with two copies of the DVD, AND I’M GLAD!

Saw this when I was a kid and wore out the record. They actually did do a scene with the Arkenstone (and it’s almost a big as Bilbo), or at least did stills for it, which still can be found. I want to say it might have been in the record – which included a booklet.

I remember seeing this as a young teen when it first aired on television. The Hobbit was a favorite book for me and I was horribly offended at Gandalf the Cliche and the Disnified dwarves peeping shyly from behind the trees and the creepy-looking Elrond… I turned it off halfway through. Vrawp!

Still really interested in that essay on the Rankin/Bass Return of the King promised when this 1st ran this past September.

The first book version of The Hobbit I ever had was the Rankin-Bass illustrated hardcover. Still have it too, and I have to admit it was this version that shaped my views of some of the characters, such as Gandalf. Love the music and the voices. If I think about it, I can hear the Smaug from the Rankin-Bass movie when I read the book, and the song The Greatest Adventure has remained a favorite in my memory for years.

I quit reading at the stupid and false accusation of ‘racist aspects’

the orcs are basically distorted elves manufactured by magic…(my interpretation).

i have read LOTR and the Hobbit many times over the years and never ONCE did I glean real world racism as having any footing, neither in book nor celluloid.

i watched this version of the Hobbit when it came out on television and it was OK to me, though I hated the singing. Gollum was the impressive character voiced by Brother Tim, I believe who showed up on David Letterman a handful of times ten or so years later.

sorry to not complete reading, but I am bored by attempts to read racism into everything just because it is the faddish thing to do

Thanks for this! I too was one of those 70s kids, and I can assure you I loved this special when it first aired. It’s great to see others enjoyed the box LP set, too: I have happy memories of doing homework and making D&D maps while it played in the background. I still have the originals, but nothing to play them on any more, alas.

“Fifteen birds! / In five fir trees!”and the sweet oboe (?) solo just after Thorin lurches damply out of his barrel, are my favorite musical bits.