Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

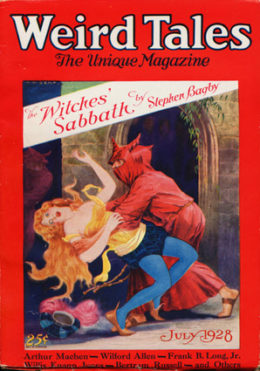

This week, we’re reading Frank Belknap Long’s “The Space-Eaters,” first published in the July 1928 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

“Suppose there were a greater horror?”

Summary

Horror comes to Partridgeville in a blind fog and eddies around the farmhouse where narrator Frank and friend Howard sit. Howard, a tall, protuberant-chinned fellow of a “wildly imaginative nature held in restraint by a skeptical and truly extraordinary intellect,” writes furiously. His weird tales hold considerable evocative power—one purportedly sent a young college student to a madhouse. But tonight Howard’s struggling; though he “intuitively” grasps the monster he’s trying to describe, he can’t find the words to convey “the strange crawling of its fleshless spirit.”

The friends fall into a lively discussion of the aesthetics of horror and the impossibility of expressing a thing “utterly unearthly, that makes itself felt in terms that have no counterparts on Earth.” They’re interrupted by pounding at the door. Frank admits neighbor Henry Wells, who’s met that foggy night with a “funny accident” while driving through Mulligan Wood. Something wet fell on his head; Henry puzzled over what looked like a calf’s brain. He stared up into the canopy, glimpsed something long and white running down a trunk. The thing was thin as wire, but somehow like a huge white hand that walked on its fingers down the road.

Henry whipped up his already bolting horse. They were clear of the wood when Henry’s brain went cold. Agonizingly cold, “roaring with raging cold.” Ten minutes saw the end of the pain, but at home Henry discovered a hole in his temple, like a bloodless bullet wound. He shouldn’t be alive.

Howard shouts that Henry’s told them an absurd lie. He must be drunk, yet he’s managed to describe a horror Howard could not capture! Frank calms him, and Howard examines Henry’s wound. But then Henry shrieks that the terrible cold has returned. He has to get out, for the thing wants room, his head won’t hold it!

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Henry dashes out into the fog. Mad, Howard concludes. Frank’s less sure but agrees to wait until morning to intervene. Then wailing starts, from the direction of Mulligan Wood.

The friends gird themselves to investigate. Through the swirling fog, the trees of Mulligan Wood look like twisted old men, and the heavy air is rent with screams that “they are eating my brain.” They find Henry collapsed but alive. A menacing drone begins—a warning that the things have broken all barriers. Revived enough to run, Henry beats the others back to the farm and, Howard hopes, safety.

But no, because Henry’s degenerated to crawling on all fours. He attacks Howard like a rabid dog before being knocked unconscious. Frank summons a doctor, who says he must perform emergency surgery. With Frank holding a lamp, the doctor exposes the afflicted man’s brain and sees something that makes him close the skull at once. Voice breaking, he tells Frank he saw, “oh, the burning shame of it… evil that is without shape, that is formless… they have laid their mark on him and they will come for him.”

The doctor decamps. Frank and Howard flee the doomed farm in Frank’s launch. The fog begins to lift, and they hope to make it to open sea. Then they look back to see Mulligan Wood’s on fire. Above it towers a “vast formless shape.” If they see it clearly, they’ll be lost!

But Frank remembers the primal symbol older than the world and all religions. He lights some cotton waste and signs a cross in the air. Howard repeats the sign boldly, and the shape loses definition and vanishes.

Back in Brooklyn, Howard tries to write down what happened in Partridgeville. He’ll have no peace until he’s made readers understand the unspeakable thing. He and Frank hash over the horror. Howard concludes the things have gone, defeated by the primal sign, for their influence hasn’t spread.

Then let them forget the incident, Frank urges. Stop trying to write about it. Never, Howard cries. He’s almost captured the terror without form, and when he’s done, he’ll have surpassed Poe and all the masters of eldritch fear!

That way madness lies, insists Frank. Three days later, Howard gives him a manuscript. Frank reads in a “frenzy of loathing,” for Howard’s masterpiece “violates privacies of the mind that should never be laid bare!” Refusing to discuss the abomination, he leaves.

Howard telephones after midnight. They’ve come back, the droning, a dim shape, and though he’s made the sign, they grow stronger!

Frank rushes to his friend’s house, terrified that by writing his story Howard’s become their priest on Earth. He climbs the stairs to the sound of Howard pleading in agony: “Crawling—ugh! Oh, have pity! Cold and clee-ar… God in heaven!”

Frantic, Frank makes the primal sign, doubting its power. He reaches Howard’s door, swings it open, sees Howard on his back, warding off some “vision unspeakable.” Something compels Frank to look up to a darkly shrouded shape that pours blinding shafts of light into Howard’s head, while the pages of his story whirl through the shafts like crazed moths.

Frank screams and covers his eyes. Then the Master of the light screams also, for the sign Frank made below, that “high and terrible mystery,” forms itself in the room and shrivels the Master in white and cleansing flame!

Frank is saved. But his friend is dead.

What’s Cyclopean: Poe is so prosaic with his “liquescent Valdemars.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Lovecraft’s dismissiveness of rural folk is actually a bit toned down here.

Mythos Making: This story is literally about Lovecraft facing down a horror he’s been trying to write about (and then getting taken down by it once he succeeds).

Libronomicon: Dee’s Necronomicon seems awfully Christian.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Howard initially chalks up the neighbor’s alarming story to “a nightmare-fungus conceived by the brain of a lunatic.”

Anne’s Commentary

In an RPG I used to play, a certain person constantly tortured or tried to kill off my characters. I assumed this person didn’t like me, but now I realize that fictive violence was a sign of deep friendship. You know, like Lovecraft’s and Long’s. I can see Lovecraft finishing “Space-Eaters” and chuckling through gratified tears, “Aw, Frank must love me to let formless monsters from alien dimensions suck out my brains!”

That’s bromance, compounded by the praise “Frank” heaps on “Howard,” a “wildly imaginative nature” nicely tempered by a “skeptical and truly extraordinary intellect.” Poe and Hawthorne, Bierce and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam would have delighted in Howard’s tales. He evokes sensations “never seen, heard or smelt on the familiar side of the moon.” He writes with such force as to drive the sensitive mad and spark indignant letters. Plus he’s a theoretician of the weird—the first part of “Space-Eaters” practically summarizes Lovecraft’s monograph Supernatural Horror in Literature, published in 1927, a year before Long’s tale. Compare two passages:

[From Supernatural Horror] “Children will always be afraid of the dark, and men with minds sensitive to hereditary impulse will always tremble at the thought of the hidden and fathomless worlds of strange life which may pulsate in the gulfs beyond the stars, or press hideously upon our own globe in unholy dimensions which only the dead and the moonstruck can glimpse.”

And:

[From “The Space-Eaters”] “ ‘If a man wishes to write and… convey a sensation of horror, he must believe in everything—and anything. By anything I mean the horror that transcends everything… He must believe that there are things from outer space that can reach down and fasten themselves on us with a malevolence that can destroy us utterly…’ ”

“Howard,” though, denigrates the very masters Lovecraft lauds in Supernatural Horror. Really, Radcliffe and Maturin, Poe and Hawthorne, what do they rely on but tired props and hellfires and gore? Stoker relies on conventional vampires and werewolves, Wells on “pseudo-scientific bogies.” Why, even Blackwood—ouija boards and ectoplasm! (“Howard” forgets that Lovecraft excuses Blackwood’s cheap spiritualism since his best works “evoke as does nothing else in literature an awed and convinced sense of the immanence of strange spiritual spheres or entities.”) Alas, we’re all physical beings scared of injury and death. Alas, we’re descended from barbarians whose folklore transmuted mundane predators into legend. Oh, where’s the cosmic horror? To describe the utterly alien, perhaps only a mathematician could succeed!

Or else a mere yokel like Henry Wells. Because “Howard’s” right to rage at the irony of it all. He’s been pontificating for pages about the impossibility of capturing ultimate horror, and in bumbles this rube who manages in colloquial speech to outpunch Howard’s sweat-polished prose! The nerve of the guy to describe a dropped brain so well and make his listeners see how the fog brings into stark relief trees like old men, “tall and crooked and very evil.” Unfair for his simple mind to translate the formless into one of the most chilling images I’ve ever read: a white arm of uncertain diameter, racing down one of those evil trees to send its hand fingertip-walking in the road, a huge hunting spider. Later he ups his own ante by describing the unseen (yet psychically seeable) enemy as something “all legs—all long, crawling legs” that buzzes “like a great big fly.” And when Henry tries to articulate what the invader feels like, he doesn’t belabor figures like the uttermost glaciation of space between leering galaxies. He reaches for the concrete: ice held on the palm until it burns worse than fire, a brain laid on ice for hours, a furnace roaring with raging cold.

I wanted Henry to keep talking—that is, for Long to keep talking through Henry. Interesting to note the real Howard often used an unsophisticated (rather than a professor’s or aesthete’s) voice to put across a jolt of horror. There are the old man’s cannibal maunderings in “The Picture in the House”; the frantic reports of Dunwich residents beset by invisible death; the history of Innsmouth as told by Zadok Allen; and Nahum Gardner’s dying account of the Color in his well.

To close out Derlethian Heresy Month, what better than to feast on an early non-Derlethian version? Long doesn’t bother with the Sign of the Elder Gods as symbol of primal goodness—that’s too hard to draw when you’re in a hurry, especially if you’re “drawing” with burning cotton. No, the sign of the cross will do fine; it works with vampires, and these things are kinda vampires, right? One protective talisman to handle ‘em all. Except for the Hounds of Tindalos, who’d find the right angles of a crucifix perfect ports of entry.

So much for a universal deterrent. The cross has an additional drawback: You have to be pure of heart to wield it. Which must explain why Howard’s crosses fail him in the end. He’s written himself into a High Priest of Interdimensional Evil!

Weird fiction, children. It’s a dangerous thing.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

It’s been a while—over three years—since we’ve read a Frank Belknap Long story. There’s a reason for that, and that reason is mostly my deep disappointment in the Hounds of Tindalos on his page, as compared with the Hounds in my head. (But not literally in my head, a distinction I feel compelled to make this week.) This week’s read doesn’t open with any greater promise—I can hardly think of a worse way to start a cosmic horror story than with an ostensible Necronomicon passage extolling the power of the cross. Prosaic indeed.

But I surprised myself by enjoying the stupid thing. Sure, it reeks of dualism, presaging the Derlethian Heresy by at least a decade. But the eaters are genuinely scary on the page, and Frank and Howard are loads better company than blowhard/infodumper Chalmers in “Hounds.” Howard is clearly written with great affection, but without softening. I absolutely believe that the “your brain is prosaic” bit was taken from life. And the scene where he gets furious at a man who’s just been traumatized by cosmic horror—because he’s just spent a deeply frustrating writing session trying and failing to describe such a horror—is kind of hysterical. I’ve never been that much of a jerk, but possibly only because no one has never raced in while I was blocked to describe exactly the thing I was having trouble depicting. My wife just took one look and said, “Yep. Writers.”

Even if the main characters weren’t in fact Long and Lovecraft, it would be refreshing to read a story with an intense central friendship that wasn’t destructively homoerotic and/or weirdly obsessive on the narrator’s side.

You just know, too, that half of Howard’s motivation in running out to rescue that screamer from the woods is to get closer to his source material.

But then there’s that freaking cross. I don’t care whether you’ve got Dee’s Necronomicon or the original Alhazred, it shouldn’t promise comfort and easy defenses against the uncanny. I don’t like it when it’s the elder sign, and I don’t like it when it’s the sign of the cross. I don’t like it when you can just wave a symbol in Cthulhu’s general direction and get some breathing room, and I don’t like it when you need to call upon True Faith to make it work. Even there, Long almost makes this stupid idea work by having Frank fall into doubt at a key moment. And then… I really don’t like it when Grace comes shining from the heavens to protect someone from extradimensional abominations.

I do like the way Howard’s death is presaged by his earlier speculation about the eater clothing itself in human thought. Of course, describing it in words does just that. The image of the Thing shining above his body, pages of the story swirling through it, is kind of perfect, even in the midst of a scene that is otherwise a complete mess. How many authors could resist writing their perfect story, even knowing the consequences?

When we covered “Hounds,” we quoted descriptions elsewhere claiming it as the first non-Lovecraft Mythos story. But “Space-Eaters” came out a year earlier, and the Eaters certainly fit into a universe of Colors and fungal vampires, not to mention being canonically (if fictionally) a scary thing first imagined by Lovecraft. Joshi apparently gives “Eaters” the tentative place of honor, and I’m inclined to agree.

Finally, speaking of places of honor—I’ve spent a good part of this evening trying to search out questions like “What’s the history of the Derlethian Heresy?” And I keep bumping into Lovecraft Reread links. I mention this because self-referential self-congratulations seem in the spirit of “Space-Eaters,” but also because there are no good articles on that topic online, and I’m hoping someone better steeped in non-fictional Mythosian history will be able to enlighten me in the comments.

Speaking of things that are hard to describe, next week we’ll look at Nick Mamatas’s “That of Which We Speak When We Speak of the Unspeakable.” You can find it in Lovecraft Unbound.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.