Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

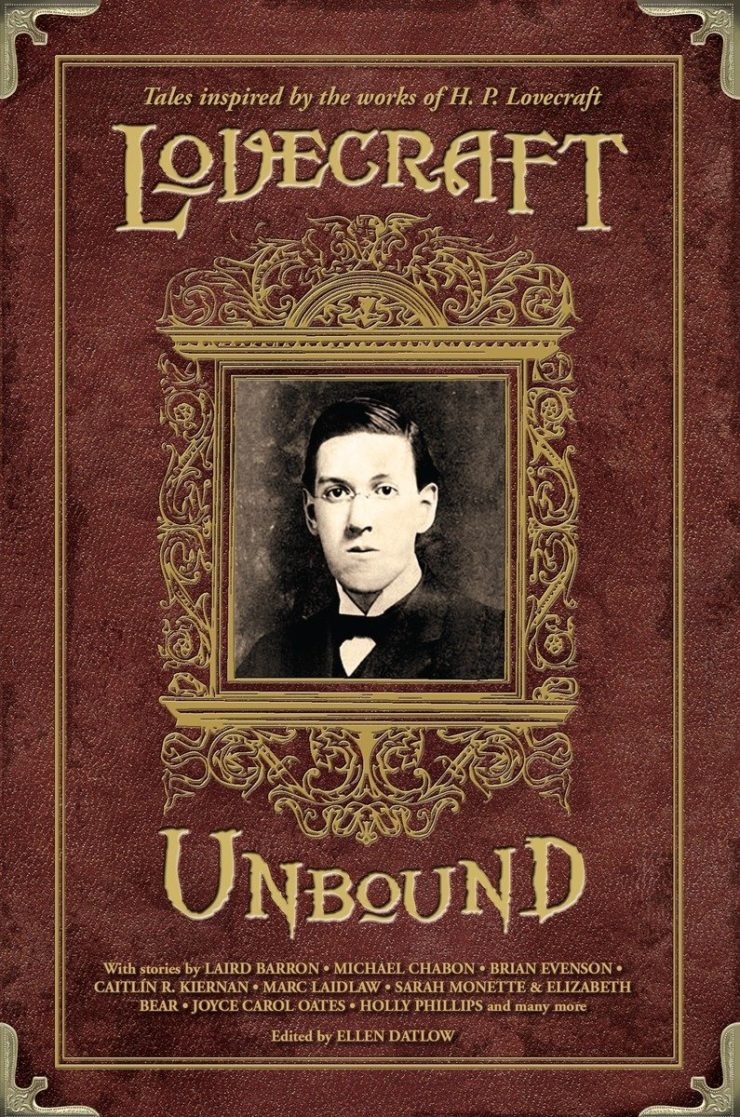

This week, we’re reading Nick Mamatas’s “That of Which We Speak When We Speak of the Unspeakable,” first published in 2009 in Ellen Datlow’s Lovecraft Unbound anthology. Spoilers ahead. Trigger warning for mentions of sexual assault.

“It’s the end of the universe and it’s a whistling squid. Greeeeat.”

Summary

Jase, Melissa and Stephan are orphans of the apocalypse, sheltering in the mouth of a cave, drinking what may be the last bottle of whisky in the world. Jase and Melissa have been traveling together for a couple months; Stephan just joined them the night before. In the flickering light of their kerosene lamp, Jase (a self-proclaimed prophet) talks about how lucky they are “to be here for the end. To see the sky when the stars blink out, to watch the seas boil and the Elder Gods crush us all.”

Jase, Melissa remarks, “is all about the tentacles and the worship. He likes the drama.”

The “drama king” continues. Another great thing about the end, there’ll be no more love, that supposed “all-powerful, all-encompassing force.” The force that leads lost dogs home to their masters, that makes cancer all better, that brings meaning to life, that makes people love you back, even if you are a fat drunk. His parents seemed to love him, and he was “trained… with food and physical contact to love them back.” Then they got in a car wreck and died after months of suffering, and after a while he didn’t love them anymore. “Love fades,” he says, “like a rash.” What’s more, that kind of love is boring. Everything’s boring.

Melissa tells a story about a boyfriend who went to prison. He said everyone there looked forward to their hour of exercise, even if it meant getting shivved or raped. Otherwise prison was just boring. Maybe she loved that boyfriend, but more so when he wasn’t around.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Jase is having one of his prophetic spells, trembling with arms spread wide and doing “tongue tricks.” Does Melissa believe all his “yoobalalala stuff” is real, Stephan asks. Melissa says she doesn’t know if Jase is real, but it’s sure real. No denying that now, after New York. Melissa started following Jase after the Mississippi horror, when the water began to swim with “carpets of tadpoles with the faces of men.”

It annoys Stephan that people always forget about China. How the Chinese nuked the thing that had appeared “all hungry eyes and inside-out angles.” How the thing rematerialized the next day, good as new and radioactive.

“Can’t you see ‘em in the sky,” Jace asks, “when you look up and squint and concentrate on the ajna chakra? The dark tentacles in a sky just as dark—”

The end of the universe, and it’s a whistling squid, Melissa says. More quietly she adds, “Ah, here they come.”

She points to dark woods below the cave. Stephan makes out shoggoths oozing into the clearing “like an oil slick.” Slowly they slide uphill, while Melissa confides that she got into “this sort of thing” years ago, as a kid. “It just felt good, that there was something bigger than yourself out there. To think you knew something that other people didn’t know. Well, everybody knows now.”

Stephan agrees. Most people didn’t go insane, though. They kind of got used to it. Except maybe for Jase. Is Melissa in love with him?

Maybe. “He’s like looking in the mirror” and thinking that might have happened to her if she had never gotten okay with “doing the dishes even if they’d just get dirty again—”

Jase stops thrashing and babbling, too late. A shoggoth crashes down on him like a wave, crunch. Shoggoths drag and slide closer on their pseudopods. Melissa sucks the last of the whisky into her mouth and turns the kerosene lamp down. In the darkness Stephan hears his and Melissa’s hearts beating. The shoggoths block the cave mouth. Melissa spits whisky across the lamp’s still-burning wick and forces the lead shoggoth to retreat, shriveling.

But then a few more come.

What’s Cyclopean: At the end of the world, anything can sound profound. Jase, in the midst of his ostensible prophecy, “gibbers” about “crazy backwards ninth-dimensional geometry.”

The Degenerate Dutch: At the end of the world, a lot of people randomly bring up sexual assault in conversation.

Mythos Making: At the end of the world, the elder gods rise, shoggothim are on the hunt, and the Mississippi swims with carpets of human-faced tadpoles.

Libronomicon: There may well be books at the end of the world, but Jase’s crew has left them behind in favor of more beer.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The rise of the elder gods doesn’t make people go insane or anything. They get used to it. You can get used to anything, even the end of the world.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Of what do we blog, when we blog about stories of the unspeakable? I’m tempted to give up entirely and post random insightful-sounding discussion of unrelated topics. It would be in keeping with the choices made by Mamatas’s characters, at least, and possibly a better commentary than I can actually manage by commenting directly.

At the end of the world, there will be self-referential tongue-twisters.

At the end of the world, “Unspeakable” suggests, people will continue to be as insipid as they’ve ever been. Faced with the evidence that human concerns are meaningless in the face of an uncaring universe… they will demonstrate, as they always have, that it doesn’t take cosmic vistas to render some human concerns obviously meaningless. You don’t have to be a shoggoth to be bored by drunk frat boys.

Jase is the sort of decadent hedonist who is totally willing to give up pleasures (at least briefly and hypothetically) in favor of more decadent ennui, and once-in-a-very-short-lifetime observational opportunities. I suspect he’d get along with the bored protagonists of “The Hound,” or the bored grave robber in “The Loved Dead,” except that he lacks their dramatically misguided passions. He doesn’t believe in love at all since his parents died, which is the sort of thing that does tend to break people’s faith. Becoming a prophet is a less typical response to trauma, but could easily become more common after the elder gods rise and start destroying cities.

Melissa is slightly more interesting. She’s the hipster of cultists—she liked knowing something that other people didn’t know, only now everyone knows about the elder gods, so worshipping them is no longer cool. And she does make a last-ditch effort to shrivel a shoggoth before the next one gets her. But the next one does get her, just like she knew it would. Getting eaten by a shoggoth is the next big thing, you know?

So this is a very clever story, making clever points about the meaninglessness of existence and of human interaction. It gives the reader—at least, this reader—a sort of Cthulhoid perspective on the protagonists. “Are they worth watching for a few more minutes? Would my existence be made marginally more pleasant if someone ate them five minutes sooner? Should I go back to sleep now?” Alas that I’m not the sort of decadent hedonist who revels in ennui, no matter how cleverly self-referential it is. [ETA: And I’ve never read the Carver story so missed half the references, which helped no things.] I was pretty good with them getting eaten, and would’ve been perfectly happy if it had happened five minutes sooner.

Anne’s Commentary

What if during his drinking days (or worse maybe, after them) Raymond Carver had experienced the Cthulhu Apocalypse? Would he have quickly succumbed to the minions of the Elder Gods, or would he have had time to retreat to a cave with a convenient coffee-table boulder, there to continue writing stories like “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” except with an eldritch twist? Since he was brought up hunting and fishing, Carver could have survived by bagging the odd Byakhee bird and netting human-faced tadpoles. And because of that cataclysm that took out New York, he likely would have been free of Gordon Lish, his infamously heavy-handed editor. When the Cthulhu Spawn squelched into Manhattan, I’m sure they went for the editors first, brandishing manuscripts in every tentacle.

But that’s just one line of speculation concerning the end of the world. It’s not Carver but Mamatas who gets to speculate in “That of Which We Speak When We Speak of the Unspeakable,” a top contender for Title the Most Fun to Say in a Oxford-Don-ish Accent. What Mamatas envisions is the triumphant return of the Elder Gods to their former dominion, our Earth, as seen through the whisky-bleared eyes of three ordinary people, the sort of characters Carver specialized in: unexceptional (for all Jase’s prophetic pretensions), on the sad-sack side, volubly teetering after their truths before the dark comes.

In Carver’s story, two couples sit around a kitchen table, swigging gin and tonics and chewing over the vagaries of love. Mel does most of the talking, or pontificating depending on the listeners, which apparently include Mel’s second wife Terri. She needles Mel with jabs that more closely target his tender spots the more gin the party imbibes. The other couple, Nick and Laura, say little. They haven’t been married long, so are still in love. Just wait until they’ve been together longer, Terri jibes. Oh, but she’s only joking, of course she loves Mel and he her. And slowly the tension rises. Finally, instead of going out to eat as planned, they sit silently around the table, and narrator Nick thinks: “I could hear my heart beating. I could hear everyone’s heart. I could hear the human noise we sat there making, not one of us moving, not even when the room went dark.”

“That of Which We Speak” gives Jase the “Mel” part; as Mel has a right to dominate the conversation because he’s a cardiologist, Jase naturally dominates because he’s a prophet, maybe. Like Mel, Jase is down on love. It doesn’t make sense. It’s a simple matter of proximity. It doesn’t last. Good riddance to it in the age of Elder Gods. Melissa seems as jaded as Terri, but she’s loved before, a troubled boyfriend who ends up in prison, an echo of Terri’s abusive ex, Ed. She “kinda” loves Jase, as the mirror image of herself if she’d gone mad in the face of the Coming. Stephan, like Nick and Laura, is largely an auditor. Observing, rather than doing, has always been his role—he wonders if he could get himself sent to prison like Melissa’s boyfriend, where he could enjoy the suspense of whether someone might stab or rape him, something. In the end, he continues to observe, not act, but like Nick he owns the most poignant lines, Mamatas’s echo of Carver: “Stephan could hear his heart beating. He could hear Melissa’s heart beating too, he thought, even over the wet-shoe squelching noises of the shoggoths. He could hear the human noises he sat there making, not moving at all, as the cave went dark.”

Human noises! Beat of the heart, sigh of the breath, chafe of skin on skin, maybe a groan or sob? Not words, though. Just the honest inarticulate, what humanity is reduced to when the light fades, whether from a kitchen or a cave, whether the danger is baring too much or the slow but inexorable approach of shoggoths.

Shoggoths must be among those things which are unspeakable. None of Mamatas’ characters speak of the protoplasmic horrors, though Melissa at least appears to have been waiting for them. In fact they don’t speak much of any of the horrors of the apocalypse. We get only tantalizing hints: the Mississippi tadpoles, China’s desperate nuking of what may be Cthulhu Itself. As for New York, something really horrible must have happened there, but we don’t hear what. People supposedly always bring up New York, but not these three. New York is the unspeakable unspeakable, or else it’s the unspeakable that’s been spoken so often it’s become an old story, commonplace. Boring.

Could that be Mamatas’ point, that Lovecraft might have underestimated humanity’s capacity to normalize the abnormal, however “unspeakable,” “unnameable,” “unimaginable”? Melissa confesses that she got a thrill out of the Cthulhu Mythos before the Mythos came true. Before the apocalypse, she could feel special in her esoteric knowledge. She could enjoy the thought of “Elder Gods,” beings bigger than mere men. Now she’s not special. Everyone knows about the Great Whistling Squid. Now Cthulhu’s become as real as—washing dishes. Another aspect of grown-up life to be accepted and endured.

Stephan agrees. People have gotten used to the “unspeakable,” and they haven’t gone any crazier than if it were a war or epidemic. Except maybe for Jase. Jase, unable to face the horrifyingly banal truth, retreats into delusion. He’s a prophet—according to Melissa, even a worshipper of the Elder Gods. His ajna chakra or Third Eye has opened, and he can see the dark tentacles in the dark sky! He looks forward to watching the stars blink out and the seas boil and the Elder Gods crushing humanity! Give him high romantic drama or give him—

Yeah, death, as Melissa might drawl. At least Jase goes out with irony—in the middle of a prophetic fit, his delusion breaks, and he tries to flee the minions of his gods. Melissa the practical blows a defiant fireball. It works, shriveling a shoggoth. Too bad she’s now out of flammables, but the apocalypse isn’t out of shoggoths. Stephan, most ordinary of the ordinary, just freezes, making human noises.

So how do the makers of human noise go out? To paraphrase T. S. Eliot, this is the way the world ends, this is the way the world ends, this is the way the world ends, not with a bang but a crunch.

Crunch of bones under shoggoth bulk, that is.

Ew.

Next week, we return to The Weird for Tanith Lee’s “Yellow and Red.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

It’s a bleak, bleak story. There are ways in which it meshes very well with Lovecraft’s view of the mythos in an uncaring universe and ways it stands counter to those views. HPL wouldn’t understand the apparent indifference and acceptance of the end that we see here, but it may be just as valid the crushing madness he envisioned. Indeed, today it may be the common response we would see, people struggling to cling to a sort of normality even as reality turns inside out.

I know nothing of Raymond Carver or the story Mamatas is riffing on. I do have to ask how well he captured the voice of the original. His novel Move Under Ground really feels like it could have been written by Jack Kerouac in response to the rising of R’lyeh. I think the only deliberate mirroring of a famous author’s voice that I’ve seen that comes close (not counting things like Lovecraft’s imitation of Dunsany) is Harry Turtledove’s Hemingway pastiches here at Tor.com. For all that it’s a short novel, Move is probably too big to cover here, but is well worth devoting some of your copious free time to, especially if you have any interest in the Beats. (It features not only Kerouac, but Cassady, Ginsberg and Burroughs as well.)

I was unfamiliar with this story, but the concept seems interesting enough. Funny enough, many years ago I played a game of the Call of Cthulhu tabletop pen & paper RPG and in it someone had the big idea of nuking Cthulhu, who simply re-materialized again, but now he was also radioactive! Turns out it was an idea out of an article in an issue of Dragon Magazine, which suggested how to deal with players who weren’t afraid enough of Cthulhu and wanted to solve everything with increasingly bigger guns in a universe where the protagonists are not heroes or superheroes, but merely investigators.

the story illustrates an interesting fact about lovecraft: the horror of a shoggoth derives from the way in which its existence challenges his cherished beliefs about the place of (white) men in the universe, not just the fact that it is big and squishy. these characters believe in nothing at all, and thus the apocalypse barely horrifies them. cf. nietzsche’s madman, ranting about the terrifying death of god — to a bunch of confused atheists, who are too foolish to understand why that’s a problem (the gay science section 125 is halfway to cosmic horror, frankly).

I still haven’t read this one, but I second the recommendation of Move Under Ground, which could’ve easily been just a gimmicky pastiche but made a really strong impression on me. Similar themes to this story from the sound of it, but with a broader scope and not quite as bleak.

Eep, no thanks. I’m often fine with creepy, but not with apocalyptic.

One of my English teachers named his dog Carver, after Raymond. I have no idea why.

*gigglesnort* I would read a story about that.

@1 Move Under Ground is terrific. I kept thinking of it reading the review. I strongly recommend anyone read it.

Here’s an off topic question for Anne and Ruthanna: do you only want story suggestions to read that involve fiction published in (print or online) magazines or books? Can one suggest stories posted on a blog, for free? Assuming the author gave you his/her permission, of course?

(Jihadi Colin is the nom de plume of Biswapriya Purkayastha)

@AeronaGreenjoy

I just wrote one.

@AeronaGreenjoy: One of Carver’s better-known poems is “Your Dog Dies.”

Poets will be poets. And English teachers will have their fun.

you wonder how long this can go on.

As for people getting used to the unspeakable, I was reminded of the immensely popular– at least, they used to be popular– “Left Behind” series. In which Yahweh might as well be one of the Elder Gods, destroying one-third of humanity in his initial manifestation, including all the children. And no one seems to notice!

What if getting eaten by a shoggoth does become the next big thing, but then shoggoths stop eating people because it makes them deeply uncomfortable? See, the mindset that would perceive being crushed and absorbed by a shoggoth is in some way Not Okay–depressed or suffering something incurable and progressive, most likely–and shoggoths absorb the memories of their prey as well as their bodies. And they would like to go back to eating penguins, because penguins don’t ruminate upon the joylessness of their existence or remember when the drugs stopped working. So the best way to make a shoggoth go away is to spread your arms wide and run joyfully toward it, or lie down in its path. To keep shoggoths out of your house, build a wheelchair ramp or put a No Open Flames–Oxygenator in Use sign on the door.

@7 – Here are some free online sites for Lovecraftian fiction.

https://lovecraftzine.com/magazine/ – Just go to the website editions.

I was going to link to Innsmouth Free Press but they have taken down their free fiction, alas. This magazine was pretty good in its day.

http://www.infinityplus.co.uk/stories/colderwar.htm – Here is A Colder War by Charlie Stross.

It is a bit of a pain in the backside, but if you search around the Tor website, they have published quite a few Lovecraftian freebies.

It also depends whether you want to read online webcomics.

On YouTube there are free readings of HPL’s stories and some other Lovecraftian fiction to be had if you prowl around. I’ll give 2 examples.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i454o7ijabI – Here is a reading of ‘N,’ a graphic novel by Stephen King. This is simply wonderful.

Neil Gaiman’s Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar is read in 3 parts by the author. It is magnificent.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rN1HElM_ECA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oBR1HzWccqA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yNhtuHf0vnk

I never realized this one was riffing on a piece of “serious” fiction! Explains a lot…

Do human-faced tadpoles grow up to be frog-men, or is this just an exceptionally large-scale case of Signs and Portents (three-headed calves and such)?

There’s no indication anyone is shouting and killing and revelling with joy, which makes this a bit of a downer compared to the Lovecraftian version, in which at least the poor and dark and downtrodden of the Earth would be getting some fun out of the experience. It also makes it possibly a bit less horrible to certain types of white people.

@Amaryllis: the author of that series clearly finds people who aren’t fundamentalist Christians about as comprehensible as the Great Old Ones, and is therefore quite unable to realistically model their behavior in his head.

Get eaten by a Shoggoth so wimpy that it can be driven away by anyone with a campfire and a mouthful of hard liquor? I’d be humiliated.

Jihadicolin @@@@@ 7: We take suggestions from anywhere, with the caveat that our TBR pile has all the usual characteristics of TBR piles. Lovecraftian fiction blurs the line between fanfic and traditional publishing even more than most subgenres.

Right, Ruthanna, here are two by me you may or may not want:

The Abode Of Shaytan:

http://bill-purkayastha.blogspot.com/2017/11/the-abode-of-shaytan.html?m=1

and

The Girl And The Shoggoth:

http://bill-purkayastha.blogspot.com/2019/03/the-girl-and-shoggoth_22.html?m=1

I don’t mind at all being taken apart in your reviews. In fact I’m looking forward to it!

Added to the list!