A man who can’t feel pain has been bioengineered to be a killing machine, but he refuses to give in to his fate.

Mars stands in the middle of the highway, knees locked, head tipped back. The sky overhead is choked with harmattan dust. There is so much dust he can stare directly at the rising sun, a lemon-yellow smear in the dull gray. There is so much dust it looks like everything—the scraggly trees, the sandy fields, the road itself—is disappearing, as he often wishes to disappear.

He used a pirate signal to monitor the progress of the autotrucks coming from the refinery in Zinder, loaded with petroleum. He watched them snake along the digital map. Now he can feel them coming: Their thunder vibrates the blacktop under his feet. They move fast and their avoidance AI is shoddy. In the low light, they will not see him until it is too late.

Mars takes a breath of cold, dry air. He bows his head, shuts his eyes. He can hear the first autotruck now: roaring, squeaking, clatter-clanking. He imagines it as a maelstrom of metal hurtling toward him. His heart thrums fast in his chest.

When the truck flies around the curve, Mars realizes he still wants to live. He tries to dive aside. The impact splits his world in half.

Dusk falls and Mars is still waiting beneath a twisted baobab for Tsayaba, the old woman who claims she can find anybody in this city, anybody at all. So far only a stray dog he met early this morning has shown up. It sits in front of him, panting expectantly, tail thumping the sand.

“You again.”

Buy the Book

Painless

The animal is gaunt, with fat black ticks studding its neck and shoulders, burrowing deep into matted fur. It has cuts on its backside from wriggling under some jagged fence. But it is luckier than some of the other strays here. Mars saw a man with an infected eye implant roving the streets with three skeletal dogs chained to his waist, intending to sell them down in Nigeria to a tribe that still eats dog meat.

Mars takes out his nanoknife, the last piece of military equipment he carries. The stray recognizes it and starts to salivate.

“I spoil you, dog.”

Mars dices up his thumb and then his index, flicking the bloody chunks to the ground. The stray pounces on each one and whines when Mars stops at the gray-white knucklebone of his middle finger.

“I give you any more, you’ll throw it all up.”

The dog whines a little longer, blood-specked black lips peeled back off its teeth, then finally trots away. Mars is alone again. He inspects his stumps, which are already clotting shut. He inspects the darkening street, mudbrick walls topped with broken glass or razor wire.

A slick-skinned maciyin roba wanders past on its little cilia feet, hunting for the flimsy black shopping bags half-buried in the sand. The plastivores were designed in some Kenyan genelab—for this, Mars feels a certain kinship with them—and were later set loose across the continent. They do their job well and reproduce on their own, but plastic trash has accumulated in the West African dust for nearly a century and it will take a very long time to recycle it all.

The evening prayer call is starting, a distant mumble-hum projected from the mosques. Mars is not Muslim or anything else, but he likes the sound, the ebb and flow of distorted voices. He listens to it with his eyes shut and is nearly lulled to sleep before Tsayaba finally arrives.

“Sannu.”

Mars opens his eyes. Tsayaba is old, with a deep-lined face and many missing teeth, but she stands very straight and carries herself how Mars imagines a chief would, with slow, smooth motions, with high gravity. She wears a bright yellow–patterned zani and a puffy winter jacket.

“Sannu,” Mars says. “Ina yini? How was the day?”

“Komi lafiya,” Tsayaba says. “All is well. Ina sanyi?”

“Sanyi, akwai shi,” Mars says, even though he does not feel the cold. “Ina gida?” He wants to know what Tsayaba has found, but he makes himself focus on the greeting. Things are done slowly here.

“Gida lafiya lau. Well, very well.” Tsayaba frowns, clicks her tongue. “Ina jiki?” she asks. “The body?”

Mars doesn’t understand for a moment, then realizes Tsayaba is looking at his hand. The fingers have grown back—the keratin of his nails is still spongy—but he forgot to wash away the blood.

“Da sauki,” Mars says. “Better.”

Tsayaba gives a grunt of acknowledgment, then lowers herself to a squat. “I have found who you are searching for,” she says. “I am almost certain. Early this morning, six men came with a truck. They paid the gendarmes. Now they are staying in the old hospital. But it is bad.”

“What is bad?”

“These men are killers. They have otobindigogi.” She makes her finger chatter, mimicking an autogun. “And they are here waiting for worse. They are waiting for a criminal called Musa, who will buy what they have. Musa, he was Boko Haram before the Pacification.”

“When will he come?”

“They are not sure. They are anxious. He was meant to come today.” Tsayaba shakes her head side to side, side to side. “Wahala,” she says. “Wahala, wahala. If your friend was taken by these men, I think he is not a captive. I think he is dead.”

Mars does not think so. If what he suspects is true, then Musa is not coming for autoguns. He is coming for something much more valuable.

“Na gode,” Mars says. “Na gode sosai.”

Tsayaba accepts the thanks with a brief nod of the head. She pulls a sleek black blockphone from the pocket of her coat and looks politely off into the distance. Mars takes out his own phone and taps it against hers, sending a small cascade of code equivalent to five hundred francs.

“Yi hankali,” Tsayaba says.

Mars cannot promise to be careful, but he nods and clasps the old woman’s hand once more—with his right hand, his clean hand—before he leaves.

He has a busy night ahead of him.

The kasuwa is busy despite the fierce midday sun that bakes the color out of the sky. Traders lounge under their tarp-roofed stalls, barking prices, rearranging their wares. Heaps of dried beans and grasshoppers, papayas and tomatoes and purple onions, cheap rubber shoes, 3D-printed toys beside wood carvings, bootleg phones and even a few secondhand implants bearing telltale stains. Camels slouch their way through the crowd draped with rugs and solarskin, only their bony knees visible.

“Miracle! Abin al’ajabi! Come see the miracle Allah has done!”

Miracle workers are not uncommon at the market, proselytizing through jury-rigged speakers and selling elixirs from the backs of their trucks in old plastic bottles, but this time there is a new trick that draws eyes. A boy, eleven or twelve with a sleepy smile, is standing on a woven plastic mat. Cables trail from his outstretched arms and hook into a car battery beside him. The electricity hisses and snaps, and the boy twitches but does not cry out. He only stands and smiles.

It is not a trick. Passersby come and touch the boy, certain the battery is dead, and even the slightest brush sends them reeling away in pain. His whole body is crackling with charge, but he feels nothing at all. The man who says he is his father circles through the crowd collecting coins.

“Abin al’ajabi!” he calls. “Thing of wonder!”

A hubbub builds from the other end of the kasuwa. An armored jeep, jacked up high off the ground, is bullying its way through the market, maneuvering past donkey carts loaded with metal drums of well-water. It rolls to a stop and two men in sweat-wicking suits climb out. One of them is foreign, too tall and too light-skinned to be Hausa, with a babelpod covering one ear like a spiny white conch. Both of them stare at the boy.

“Turn off the battery,” the Hausa man says, in the voice of a man whose orders are done even when given to nobody in particular.

The boy’s supposed father scurries back to the battery and switches it off. “It does not harm him,” he mutters. “You saw. You saw it does not harm him.”

“Who is his family?” the Hausa man demands. “His blood family?”

A shrug. “Ban sani ba. Ban sani ba. He said he had a brother. Dead. But not him. He is a miracle child.”

“Il est une aberration génétique,” the foreign man says, and his babelpod turns it into clumsy Hausa. He walks up to the boy and removes the cables. “You feel nothing?”

The boy nods, then shakes his head, uncertain.

The foreign man takes both of his hands and turns them over, inspecting the skin. “And you are not leprous,” he says. “You are lucky to have lived this long with no severe burns. No lost limbs. It is difficult to navigate this world without pain. Your name?”

The boy shrugs. “Yaro,” he says—child.

“You are not just a child,” the foreign man says. “I think you are a Marsili. A Mars, for short. Your body does not process pain. That makes you very special. It makes you a candidate.”

The boy tries to understand the electronic speech coming from the babelpod, but he has never heard these words. He seizes on one he recognizes and makes a spaceship with his hand.

“Mars,” he says.

The foreign man laughs. “Yes. Yes. But Mars was something else, too. Mars was a god of war.”

Before he goes to the old hospital, Mars finds a neon-lit restaurant and orders so much food the two Lebanese women who own the place send their son on his moped to beg the butcher to reopen his meat locker. Mars washes his hands in the cracked bathroom sink; then, while the family cooks furiously, he sits down outside with a bottle of Youki. He watches the lime-green holo of the restaurant sign jitter and swirl through the dark, watches moths flock to it in spirals.

The beef kebabs arrive first, steaming on their skewers. Mars slides them onto the plate and wolfs them down, barely chewing; he cannot feel them burning his fingertips or mouth. Pork works better for his purposes, but it is difficult to find here. And there is another meat that works even better than pork, but he did that only once, in the field, and he has nightmares about it still.

Lamb arrives next, only half-cooked—as he ordered it. Time is of the essence. He would eat it raw if he could stand it. Mars falls on the meat, picking the rack apart with his greasy fingers. A few young men rove past, blasting music from an ancient speaker rig, laughing amphetamine-loud. They stare at the mountain of food, but when they see Mars’s solemn eyes and the carbon-black nanoknife laid on the metal tabletop beside his tray, they give him a wide berth.

Mars remembers that meat used to make him feel queasy when he was much younger, before the procedures. Now he is a carnivore the way the maciyin roba is a plastivore. He eats until his stomach drags heavy, then eats more. The Lebanese women shift from amusement to disgust to grim professionalism as they feed him, as they watch him crack through the bones and choke down the gristle.

“Shukran,” he says, when he is finally ready for them to take the plates away.

“Afwan,” they say in faint unison.

Mars’s stomach churns when he stands up, but he has trained it to not revolt.

Three years later, the boy still has no name. He is called by a number: thirteen. He is lying facedown on a geltable, because today is his Birthday, the day all the treatments and drug courses culminate in a final procedure. Other children in the facility have had their Birthdays; he has not seen them since. He supposes they were moved elsewhere, or they died.

The boy knows the procedure is dangerous. He knows even the treatments were too much for trained soldiers to bear—the pain drove them mad. But he finds it hard to feel worried. His stomach is full of shinkafa da wake and oily onions, and there is a screen set up beneath the geltable playing procedurally generated cartoons. Not so different from another life, a vague memory in which he is wedged into the same chair as his older brother in front of a flickering screen.

Above him, hanging from the ceiling like an enormous metal spider, is the surgical unit. It tracks laserlight over his bare back and marks injection points with neat red circles. Pipettes and tubes slither into the boy’s body, puncturing his skin with a dozen small flesh sounds. He feels only a dim, worming pressure.

There is a glass tank attached to the surgical unit, and inside it is the organism. The boy has been shown it before, the mass of raw pink putty that writhes and undulates. They told him it is a sort of cancer, reprogrammed by a sort of virus, and that in a way it is human. To him, it looks nothing like a human.

An electronic signal is given and the organism is fed into the boy’s body, coursing through the clear tubes into his interstitial spaces, into the artificial pockets prepared by earlier surgeries. The boy does not scream into the geltable. He does not bite through his tongue. He feels no pain, only the strange and unpleasant sensation of a hand entering his body and wriggling its fingers.

Hours later, when he is drowsy and his eyes are bleary from focusing on the cartoons, the gel sluices away and the tubes retract. He hears footsteps.

“Be patient,” a woman’s voice begs—English. The boy has learned some English in these past three years. “Be patient, be patient. It looks like a successful bond. But we have to wait.”

“I have waited for decades,” says another voice, and the boy recognizes it. The foreign man who took him away from kasuwar Galmi so long ago. “I have to know.”

Suddenly the boy is face-to-face with him. The foreign man has slid underneath the table. His hair is grayer than the boy remembers it and his eyes are more hollow. He has a cigar cutter in his hand.

“Miracle child,” he says. “It’s very good to see you again. Please stick out your thumb for me.”

Mars can see why they chose the old hospital compound. It has high mudbrick walls on three sides and barbed wire on the fourth, which backs onto an ancient landing strip. The gate is rusty metal crenellated with spikes. The painted letters have long since flaked away. Tsayaba told him that the hospital has been abandoned for years, ever since the surgical wing caught fire and took the rest of the building with it.

Mars feels bloated and heavy as he scales the front wall, but he knows he will be glad for his full stomach later. He pauses at the top to catch his breath and looks back at the old town: a maze of mudbrick, warped by the rainy season, lit by swatches of grainy orange biolamp. It feels almost organic, like it sprang up from the ground. New buildings on the periphery are more geometric, rebar skeletons in concrete sheaths. Mosques tower over everything else, their painted white crescents pushed up into the sky like waning moons.

Most important, the highway is clear. Mars faces forward and peers down into the dark compound. The hospital is a ruin, ash and rubble. But beyond it there are housing units for the doctors and staff that were untouched by the fire. He can see light in one of the windows. That is where they will be keeping their captive.

Almost directly below him, the night guard is boiling tea on a brazier. His face is scarfed against the cold, gaps only for his eyes and a pair of trailing earbud wires. His gun is resting on a woven plastic chair across from him. His blockphone is balanced on top of it, playing yesterday’s Ghana-Côte d’Ivoire football match.

Mars drops down off the wall, raising a small puff of dust where he lands. The guard leaps to his feet and right into the nanoknife.

Mars smothers the man’s cry with the crook of his arm, yanks the blade free, then spins him around to drive it into the base of his skull. It slides through the bone and gray matter as if they were cow butter. The guard spasms and goes limp. Mars plucks the blockphone off the chair and shoves the man’s face up against the screen to unlock it before rigor mortis makes him unrecognizable.

Apart from one blinking number at the top of his screen, the man’s contacts are local. He is an extra hire, not one of the six Tsayaba mentioned. Mars feels a twist of guilt when he sees a home screen clip of the man, face uncovered and still young enough to have pockmarks, tossing a little girl into the air and catching her. He lays the body down gently. Blood trickles out from underneath, stretching red fingers through the sand.

Mars silences the phone and pockets it. The husk of the hospital looms before him: a few jagged walls, half of a twisted metal staircase. For an instant Mars thinks he can smell the burning, but it is only wood fires being carried from town on the wind. There is movement in the rubble, first the slow careful motions of more maciyin roba and then a stiff-legged loping.

Hyenas is Mars’s first thought—they say the hyenas are coming back now—but it is only a pair of stray dogs. Mars peers at them for a moment, trying to tell if one is his visitor from earlier that day. Then he heads for the housing units. Tonight, the dogs will have plenty to eat.

Three years later, the boy is a soldier and nearly a man. His identification tag says Marsili 13. He wears it on a band around his arm, because when they tried to do the subcutaneous kind his body spat it back up and pinched the hole shut in seconds. The rest of his unit calls him Mars—some of them joke that he came from there in a tiny spaceship.

There is good reason for that. From the very start of his accelerated training, Mars can do things no human can do. He can sprint for minutes at a time while the organism laps away his lactic acid and replenishes his cells. His scrawny frame can carry double its weight when the organism weaves itself into his skeletal muscle.

At first the others are scared of him. Then they hate him, for making things seem so easy. They give him cuffs on the back of his head when they pass. They drop a bucket of pinching water scorpions into his shower stall. He does not care. At night he climbs into his cot with a full belly and watches cartoons on the screen of his standard issue phone, a dull black slab that only functions during certain hours.

When they go through anti-interrogation, the water filling his lungs is only a tickling ghost. They pull him out of the tank before he drowns, but he is not sure if he can drown anymore. The other members of his unit, sopping wet, breathing ragged, look at him as if he is a god. Then they look at each other.

That night they invite him to drink. He guzzles the ogogoro until he can fool himself into thinking he feels the same crazy happy way they feel. He shows them his own version of their knife game: Instead of stabbing the spaces between his fingers, he drives the point of the blade into each knuckle in turn, moving like a blur, and by the time one circuit is complete he has already healed.

They howl. The ones who still believe in witch stuff say, Witch stuff.

“Who cares,” says one of the Yoruba men. “He is ours. You are ours, yes, Mars?” And because he knows Mars speaks Hausa: “Dan’uwanmu ne? You are our brother?”

Mars thought he did not care, but now the word makes him into a child again. He starts to weep. The others shift and fidget, uneasy.

In the morning, Mars is transferred.

They are in the last house of the row, a Western-style construction no doubt built for some European surgeon decades ago. The orchard around it is dead and withered. But there is light in the window, faint music that sounds like kuduro, and a truck and two motorcycles are parked outside. Mars even sees some clothes hanging from a wire laundry line, flapping wings in the night wind.

He circles the house like a shade. From up close, the thumping music is loud enough to send ripples through the screen porch. The bass raises the hairs on his arms. He peers through a window and sees four men sitting around a kitchen table. Playing cards slip and slide over the dusty wood. A heavy black vape sits in the center, belching smoke through the affixed tubes.

Mars guesses that the last two men are with the prisoner. He takes the stolen blockphone from his pocket and thumbs the blinking number, thinking that whoever answers it will be the leader, and the leader he will keep alive to answer questions. None of the men at the table reach for their pockets. Instead, Mars hears a whistling ringtone from behind him and realizes he has guessed wrong just before an autogun tears into him.

The flurry of bullets takes him off his feet; he slams into the side of the house and crumples. Through the keening in his ears Mars realizes the music has cut out. He hears shouts from inside. A clattering door. Voices somewhere above him.

“Kai! Who the fuck is that? Who did you shoot?”

“He was looking through the window, he—”

“Is he one of Musa’s?”

“Then Musa’s trying to rip us off. The man we had out front, he killed him.”

Mars lies very still. He can feel the organism at work, knitting his flesh back together, squeezing the metal out. He reaches for his nanoknife. The autogun sees the movement and gives a bleat of alarm, but there are friendly bodies in the way so it cannot fire, and its owner takes a moment too long to realize his target is somehow alive. In that moment Mars cleaves him open from his hip bone to his sternum.

He whirls on the others, slips under a punch and pulls the man close, making him a shield as another gun goes off. Small caliber this time—a bullet clips his shoulder and he barely notices it. Three quick stabs as he pushes forward; he drops his dying shield and drives the nanoknife into the arm of the shooter. The gun fires one last time and he takes the bullet right in the chest. For a split second his whole body shudders. Sways.

Then he’s moving again, and in less than a minute he is surrounded only by corpses. Their blood pools and wriggles through the sand like anemones. Mars can feel the organism working hard, converting his evening meal into new flesh, fresh skin. The last bullet spirals back out from his heart and drops soundlessly to the ground.

Six years later, Mars is a bogeyman. He finishes his training half in virtual and half in the field, sometimes with a handler, most often alone. He is given no rank, because he does not exist as anything but a rumor. He is given jobs instead. Most often, targets. The first time he kills, the man sputters and curses and begs and shits himself. Mars had seen people die before, but causing it is different. He does not sleep for a week.

He is told, over and over again, that he is creating stability. That he murders one malefactor to save a thousand innocents. That nobody else can do what he does—the procedure has never been successful since, not once—so he must do it. But he does not feel any higher purpose. He does what he is told because it is his habit. It grinds away at him in places that do not seem to grow back.

On one assignment he triggers an alarm and has to flee on foot. A pursuer’s bullet punches a hole through his back; he survives but a week later he learns that the bullet continued through a tin wall into the skull of a woman leaning down just so, just at the perfect height, to sweep her floor.

One assignment an explosion tears his leg off. He sees his target escaping. He needs both legs to follow. So he eats the corpse beside him, eyes watering, stomach heaving.

One assignment he plants a smartbomb tailored to a general’s DNA, but the general’s son runs into the room instead and the scanner makes a mistake Mars is not quick enough to override. He watches the boy’s body blow apart.

The other operatives, the ones who are not gods, have ways to forget. But Mars’s body flushes the drugs and alcohol from his system faster than he can consume them, and sex is of no interest to him. He knows the procedure left him sterile, but he had no desire before it either, maybe for the same reason he cannot have friendships: Other people are too fragile. When he is around them all he can see are the many ways they might die.

On some of the nights Mars cannot sleep, he stands in front of a mirror and flays himself, as if he can shed the memories with the skin. He decides there are two sorts of pain: the sharp red kind that twists a person’s face and makes them scream, and a slick black kind that coats a person’s insides like tar. He realizes that he has been feeling the second kind for most of his life.

Mars knows there is a way to escape all pain. He has delivered it many times. Long ago, his brother escaped and left him alone. So when his handler sends him north, across the border, he discards his tracker and his identification tag and almost all of his equipment. In the early morning, he goes to the highway.

Mars opens the screen door, shaking insects off the wire mesh. He steps into the house. The concrete floor is rippled with red sand. He can hear the hum of a generator. The fluorescent tubes in the ceiling are long burnt out; the lighting is sticky yellow biolamp, smeared in the corners of the ceiling and activated by a particular radio frequency.

Now that he is so close to his goal, he feels a mixture of excitement and dread. For the past three weeks, ever since he crawled away from the highway trailing shredded flesh behind him, he has been in hiding. It took him days to grow his legs back, for the new nerve endings to find their way to his spine.

After that he went out into the daji, into the bush. He wandered for a week, staying in villages or moving with the herders who needed strong and tireless backs. Some of the time he was thinking of a hundred surer methods than an autotruck, but some of the time he was just existing, and it was not so bad. Then he heard the rumor.

Mars walks past the kitchen down a dark hallway, following the sound of the generator. He is still not sure he believes. But the possibility has been growing and swelling and pushing out his other thoughts ever since he heard the story, the story of the strange creature some farmers had found on the highway.

The hum is coming from the bathroom. Mars pushes the door open. In the faint glow of the biolamp, he sees a small hooded figure slumped inside the ceramic bathtub. The generator beside the tub is hooked to an industrial drill that is churning on its slowest setting into the prisoner’s stomach. Mars switches it off. He seizes the drill with both hands and drags it backward; the bit comes free with a sucking sound.

The hooded head twitches the exact way Mars’s head twitches. He pulls the black fabric gently up and away. Shock freezes him in place. He thought he was prepared for this, but he is not. The face looking back at him is a child’s, but it is also his.

“Sannu,” he says, because he can think of nothing else to say.

“Yauwa,” the boy in the bathtub says, in a reedy voice hoarse from disuse. “Sannu.”

When Mars crawled away from the highway, he gave no thought to his other half, to the splinter of spinal column and dead legs left in the ditch. He never considered how badly the organism wanted to be whole. It must have fed on carrion, or pulled some unlucky buzzard down into itself, and slowly, slowly, shaped him anew.

But it is not him. Not quite—there was not enough flesh. Instead it is a boy he only ever saw briefly in cracked screens or windows, a boy who once stood on a mat in the marketplace with wires trailing off his skinny arms.

Mars leans forward and unties the boy’s hands. His fingers are trembling slightly. The procedure only worked once, but now he knows there is another way. If they knew, they would make a hundred more soldiers like him. A hundred more gods of war.

“Ina jin yunwa,” his other self says. “Sosai.”

Mars nods, looking at the boy’s stomach where purple scar tissue is sealing shut—he is right to be hungry. The drill must have been at work for days, and they must not have fed him. He is gaunt.

“I saw kilishi in the other room. Come. Eat.”

Mars helps the boy out of the bathtub. They go to the kitchen, and on the table a blockphone is buzzing. Mars picks it up.

“Is he ready to be moved?” the foreign man’s voice asks. “We are two minutes away.”

Mars hears the sound of a rotor in the background. They are coming by air. He looks at the boy, whose new muscle is packing itself onto his bones as he devours the dried meat.

“He is ready,” he says, and ends the call. He turns to his other self. “Some more bad men are coming. They are bringing us a transport. Well. We will steal it from them. And then we can go far away, to be safe from them.”

The boy nods solemnly. “Who are you?” he asks through a full mouth.

“Do you remember the autotruck?” Mars asks back.

The boy shakes his head. “My head is bad. I remember strange things. I think I know you. Who are you?”

For a long moment Mars does not answer. They look at each other, and Mars does not see the expressions he has grown accustomed to: There is no fear or awe on the boy’s face. Only some sadness, some shyness, some hope. It reminds him not of himself, but of someone he had nearly forgotten, someone he remembers more as a smell and a skinny arm slung around his shoulders than as a face.

He realizes he has finally has found someone who will not look at him like he is a god or a devil. Someone who is like him. But Mars can make sure the boy’s life is nothing like his life.

“My name is Mars,” he says. “Like the planet.” He makes a spaceship with his hand and launches it through the air.

The boy’s mouth twitches. Nearly smiles. He raises his smaller hand and does the same, making the noise in his cheeks. “You are so familiar,” he says. “Why?”

Mars feels a third sort of pain, one he does not know, an ache that he doesn’t want to end. “Mu ’yan’uwa ne,” he says.

The boy nods, as if it all makes sense now. “We are brothers.”

“Painless” copyright © 2019 by Rich Larson.

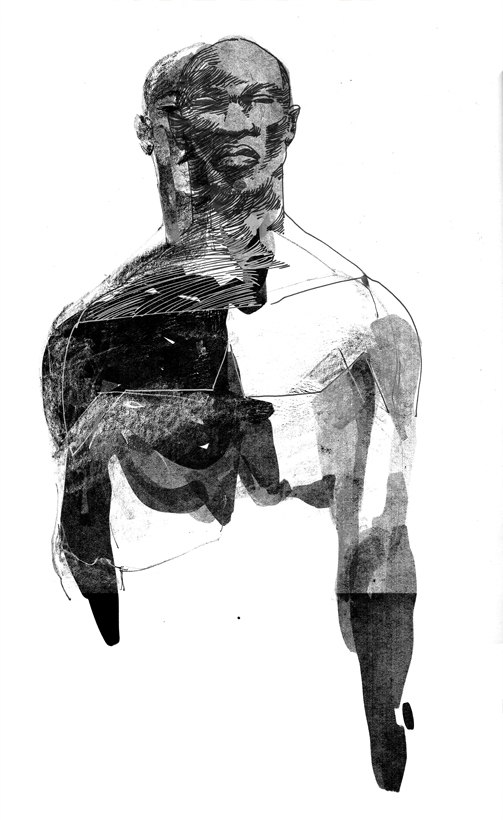

Art copyright © 2019 by Eli Minaya.

Buy the Book

Painless