I ran my “Young People Read Old SF” review series for about three years. Although it’s currently on hiatus, and while the sample size is of course small, I think it’s large enough that some conclusions can be drawn. The comments sections around the net are similarly a small sample, but again large enough that I can conclude that a lot of you are not going to like what I have to say, which is:

Love your beloved classics now—because even now, few people read them, for the most part, and fewer still love them. In a century, they’ll probably be forgotten by all but a few eccentrics.

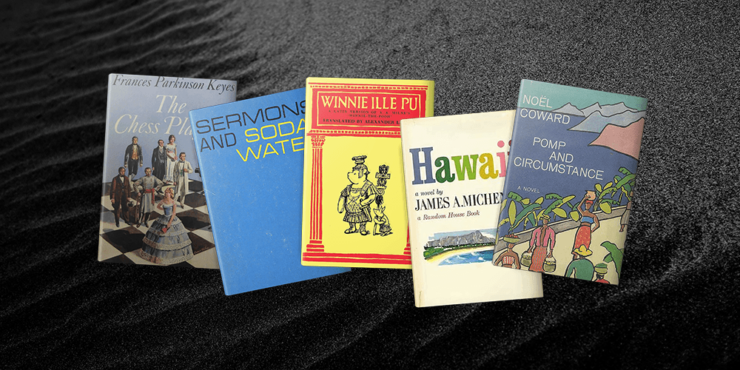

If it makes you feel any better, all fiction, even the books people love and rush to buy in droves, is subject to entropy. Consider, for example, the bestselling fiction novels of the week I was born, which was not so long ago. I’ve bolded the ones my local library currently has in stock.

- Hawaii, by James A. Michener

- The Last of The Just, by Andre Schwarz-Bart

- Advise and Consent, by Allen Drury (available in audio only)

- To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

- A Burnt-Out Case, by Graham Greene

- Sermons and Soda Water, by John O’Hara

- Winnie Ille Pu, by A.A. Milne

- Decision at Delphi, by Helen MacInnes

- Pomp and Circumstance, by Noel Coward

- The Chess Players, by Frances Parkinson Keyes

- The Dean’s Watch, by Elizabeth Goudge

- Midcentury, by John Dos Passos

- The Listener, by Taylor Caldwell

- Through the Fields of Clover, by Peter De Vries

- The Key, by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

- In A Summer Season, by Elizabeth Taylor

I am honestly gobsmacked that Kitchener Public Library has no copy of Hawaii. Michener was always a reliable author to turn to when the novels of James Clavell seemed too brief. Hawaii is interesting if only because it covers millions of years (geology setting the stage for later events). Plus, thrown with sufficient force, even a paperback of Hawaii can fell a grown man. Several grown men, if you get lucky with the ricochets.

But I digress. The point is that all of these were books that were wildly popular in their day, yet a mere twenty or so years later… actually, I’ve just been handed a note that says it is closer to sixty years, which cannot possibly be right… later, these once-popular books didn’t make the cut for my local library. One suspects that humane interrogation of my readers would reveal that for many of them, the majority of these titles ring no bells whatsoever. This is the nature of popular fiction—and of course, science fiction is no exception.

What drives this seemingly inevitable slide into obscurity? Values dissonance, rising expectations, and dumb luck.

Social values ebb and flow over decades, but the values expressed in a book are fixed.1 It may be that science fiction is more affected by values dissonance than other genres by nature of being (often) set in the future. A book written and set in the 1950s might have quaint expectations regarding the proper roles of men and women (not to mention the assumption that those are only two choices), but they would be the quaint expectations of the era in which the book is set. A novel written in the 1950s but set in 2019, one that assumed the social views of the 50s (white supremacy, women denied control of their own bodies, nebulous menaces used to justify outrageous security measures) would surely be off-putting to a modern reader. [Ha ha ha. We wish.]

Moreover, over time the minimum necessary craft needed to prosper in the field has increased. Creaky prose, shambolic plots, and paper-thin worldbuilding might have been enough for the pulps. Aspirations to write something better would be enough to make someone a superstar. Writers learn from each other, however, so some material that sufficed for 1935 seems so unpolished as to be unpublishable now.

There’s also the dumb luck factor (the unkindest cut of all). It would be nice to believe that a great book can survive entirely on its merits… but this is not the case. Even a printed book can be erased from history, thanks to any number of things that are in no way the fault of the author or the book. The author could die without a proper will, leaving their work in the hands of people actively hostile to their career.2 Publisher bankruptcies can lead to rights nightmares. When a series is spread across several publishers, some books might fall out of print. Personal tragedy could distract the author from maintaining their fan-base. Ill-conceived marketing schemes—marketing a Gothic fantasist as a horror writer just as the horror market collapses, again—could convince an entire continent’s worth of publishers that there was no more market for that author. And there are many more ways for things to go wrong.

We might not have a publishing industry at all if humans weren’t terrible at judging comparative risk.

So if you’re talking to young fans and they just don’t love the same books you do, understand that this is a natural process, one that undoubtedly happened to even older classic SF of which you are unaware. To quote the late Tanith Lee:

Sung in shadow, that was show,

Bitter-tasting are you now,

Music of sweet and delight.

We old-timers might take some schadenfreude-ish comfort, at least, from the fact that the kids’ current favorites will be forgotten one day, as well.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.

[1]Except when they are not. See, for example, Nancy Drew, whose books have been rewritten a number of times to make Nancy more acceptable to current social norms. She’s been more modest and demure, less so, as well as less overtly classist and racist, and more noir. The original Depression-era Nancy was not someone to whom you’d want to give an unfiltered interview. Her social views were formed in an era known for race-based hate crimes and worker massacres.

[2]Or the inheritors of the copyrights may be so convinced in the value of the late author’s work that they price it right out of the market.

[undefined]undefined

[undefined]undefined

Isn’t that way of all art, though? Especially pop culture. Just as few of the most popular songs of a given year will continue to be recognized by future generations, even fewer so will popular books.

And, of course, personal favorites fall buy the wayside even faster. I think I saw a hard copy of Hawaii on an acquaintance’s shelf a few years ago. I absolutely love Cloud Atlas, and its film, but I doubt either will be seen as classics. Even books considered classic when I was a child are largely forgotten. Eventually, powerhouses like Harry Potter will be forgotten.

Am I correct in assuming you also checked your local library for an English language version of Winnie the Pooh? That’s the big surprise to me from that list.

When I was in college, back in the 1980s, I would look for non-distracting areas of the library in which to study. Nothing with an interesting view–the main Yale library has internal courtyards–or books that I would be tempted to pick up and read instead of what I was working on.

In the course of that, I found a shelf of 1920s best-sellers, almost none of which I’d heard of. My hunch is that this was mostly because of marketing and changing tastes, the things James describes, plus simple numbers: books are published faster than any one person can read them, and when I’m deciding what to read here and now, I’m likely to think of new books, because of reviews and bookstore displays. And recommendations from friends, but those may skew recent for the same reasons.

(I wound up settling on a study carrel next to shelves full of Scandinavian statistical reports, which combined lack of obvious subject-matter interest with being in languages I don’t know. I have no idea why the library even owned those.)

Oh, sure. Survivorship bias lets us hope that this work or that work will escape oblivion but that’s not the way to bet.

Because I came across him at the end of his popularity, I was a bit surprised at how quickly Thorne Smith fell out of favour. In the 1970s, there were still adaptations being made of his work but a decade later? Nope. I think it was down to the degree to which his humour depended on stumbling drunks.

(That said, Thorne Smith’s Lensman writes itself).

One work that really impressed me with how little long term effect it had on popular culture was Cameron’s Fern Gully IN SPACE film, Avatar. Made crap loads of money, vanished from the public consciousness basically overnight.

Looks like mine were:

1. The Aquitaine Progression, Robert Ludlum

2. The Butter Battle Book, by Dr. Seuss

3. The Haj, by Leon Uris

4. Heretics of Dune, by Frank Herbert

5. The Danger, by Dick Francis (worst name ever!)

6. Lord of the Dance, by Andrew M. Greeley

7. Smart Women, by Judy Blume

8. Pet Sematary, by Stephen King

9. One More Sunday, by John D. MacDonald

10. Who Killed the Robins Family?, created by Bill Adler and written by Thomas Chastain.

11. Almost Paradise, by Susan Isaacs

12. Poland, by James A. Michener

13. Unto this Hour, by Tom Wicker

14. The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco

15. Floodgate, by Alistair MacLean

@@.-@ Except Disney opened an Avatar land a couple years ago and they’ve announced that Avatar and Star Wars films are going to be released every other year. As someone who hated Avatar I wish it had actually disappeared!

As someone who’s reading many older books lately, the prose style is a bit of a stumbling block. The flow is not the same and makes for short reading sessions. I will easily stop reading any book that dwells on sexism and racisim, etc. as a good thing. And yes, the volume of books available means my time must be spent wisely.

I can only hope that MZB and OSC’s works head towards obscurity with breakneck pace. They can take RH’s peak libertarian works with them too. Some books and authors deserve to be buried. I wish that genocidal bigot Ayn Rand’s works would vanish too.

It will interesting to see if the push to establish I Can’t Believe It’s Not Poul Anderson’s “Call Me Joe” as a cultural icon works any better than the effort in the 1980s to make Prince Ombra a widely beloved classic.

This is making me want to reread Bellwether again

@5: Interesting that Michener is on both lists (yours and James), in spite of the decades in between then.

I remember Taylor Caldwell being a thing. I think I read “Dialogues with the Devil” which is a weird mashup of SF and fantasy.

Reading my grandparents’ old Reader’s Digest Condensed books gave me an idea of who was popular back in the earlier twentieth century – but who talks about A. J. Cronin any more.

I’m rather fond of Somerset Maughm who at least got name-checked in the lyrics of the musical “Chess” (that’s still a thing, right?)

I earned my two and 1/2 college degrees in literature in the mid to late Seventies. Of the novels that were taught in the modern fiction classes, only one author is still remembered today. (Saul Bellows for the curious.) Books survive the generations only if they are passed from one to the next. Some adult must give a child or a younger adult a book and say, “You have to read this! It’s awesome.” It’s an easy guess that the Harry Potter series and a few other popular authors will survive, but, for most authors, it’s anyone’s guess.

Libraries are constantly culling books to make room for other books. Any book, no matter how classic, will get tossed to make room for the newest buys if no one has checked it out in recent years. A hard truth but a truth, nevertheless.

I noticed that Waterloo Public Library had the same copy of, um, Time Enough For Love that I read in the 1970s. What a narrow course there must be between read so frequently it wears out and being read so infrequently as to be discarded.

Of James’ list, I recognize the names of almost all the authors, but have only read 3 of the books and other works by a couple of the other authors. One is reminded of the conversation between Kirk and Spock in ST:IV with their discussion of Harold Robbins and Jacqueline Suzanne.

Interestingly, Advise and Consent would be considered a polit-thriller today, but veered slightly into SF as the series progressed (ISFDB includes the whole series) and he wrote a couple of other genre-adjacent things.

And I liked Prince Ombra.

Demotic prose rarely ages well. Asimov wrote an essay contrasting literary and demotic prose, comparing them to stained glass and clear glass. His point was that stained glass can be very pretty, but if you want to see what is on the other side, clear glass is the way to go. He also made a big point that clear glass is technically harder to produce, and came later than stained glass. The upshot was he was patting himself and his contemporaries on the back for finally achieving clear glass prose.

He was wrong about this, of course. He was right that there is a difference between demotic and literary prose, but wrong about the first one being new. Writers had been producing demotic prose all along, but this is a moving target. Demotic prose begins to feel dated within just a few decades. I was heavily into Larry Niven as a teen. Those books I love feel very much like period pieces today.

What Asimov missed was that the great bulk of older demotic prose was long forgotten. When he read older fiction, he was mostly reading works written in literary prose, because that tends to age much better. The exceptional older demotic prose works were still read for reasons apart from their prose, which was so dated that it was mistaken for literary prose–and often clunky literary prose at that. (Exhibit A: Mark Twain on James Fenimore Cooper.)

I don’t think that SF is actually all that different from other forms. Rather, there is a self-conscious SF community with a strong sense of its own history, which leads to people reading older SF and responding with “well, that seems dated…” Pick up one of those Michener doorstops and you would have the same reaction.

See also: The Lord of the Rings. People complain about its prose, which is distinctly literary. Had Tolkien written it like a 1950s popular novel, it mostly likely would be forgotten today.

Also, though we like to assume that we always progress socially, often citing the 50s vs now as evidence of this, this is not actually true. There have been much more progressive moments in civilization before the 50s – we (specifically America) had rather taken quite a social step backward at that time. Or for an even clearer distinction, Germany had seen more progressive times before the 40s. So even our generalized concept of steady growth social is both a bit of cherry picking and quite western-centric. We do grow more enlightened overall, for sure, but it’s more of a peaks‐n‐valleys deal, I believe. So it may make us feel good to think we’re so much better than those Neanderthal authors of the 50’s etc, but in reality, darker times than that will fail on us again (some would say have), and readers in that time will also think that they are the smart ones. But if we were to take a more self critical view, or at least a reflective one to balance our tendency towards self- celebration, we might produce fiction that can help reduce the length of those darker times. Sounds sort of like the plot of Foundation, right? There’s a book might come in handy now. Or did folks hear about that one?

1 THE CONFESSIONS OF NAT TURNER, by William Styron. (Random House.)

2 TOPAZ, by Leon Uris. (McGraw-Hill.)

3 CHRISTY, by Catherine Marshall. (McGraw-Hill.)

4 THE GABRIEL HOUNDS, by Mary Stewart. (William Morrow and Company.)

5 THE INSTRUMENT, by John O’Hara. (Random House.)

6 THE EXHIBITIONIST, by Henry Sutton. (Bernard Geis Associates.)

7 THE CHOSEN, by Chaim Potok. (Simon and Schuster.)

8 THE PRESIDENT’S PLANE IS MISSING, by Robert J. Serling. (Doubleday and Company.)

9 ROSEMARY’S BABY, by Ira Levin. (Random House.)

10 A NIGHT OF WATCHING, by Elliott Arnold. (Charles Scribner’s Sons.)

Not even going to bother looking at the library, I’ll just note that I don’t think I’ve read any of these (Rosemary’s Baby might be a possible, certainly saw the movie), and only three to four are even familiar to me by name, with the one favorite author (Mary Stewart) represented by a book I don’t recall hearing about.

1 THE CONFESSIONS OF NAT TURNER, by William Styron.

2 TOPAZ, by Leon Uris.

3 THE GABRIEL HOUNDS, by Mary Stewart.

4 CHRISTY, by Catherine Marshall.

5 THE EXHIBITIONIST, by Henry Sutton

6 THE CHOSEN, by Chaim Potok.

7 ROSEMARY’S BABY, by Ira Levin.

8 THE INSTRUMENT, by John O’Hara.

9 THE PRESIDENT’S PLANE IS MISSING, by Robert J. Serling.

10 WHERE EAGLES DARE, by Alistair MacLean.

I at least recognize most of the authors and slightly fewer of the titles.

The last time I was in my hometown I stopped in the public library (which has moved to a brand new building since my childhood days) and found at least one or two books on the shelf that were the actual copies I had been taking home back in the day — the only one I can remember off the top of my head was C.S. Forester’s The Indomitable Hornblower, a hardcover that would have been even older than me.

Alistair MacLean was huge a few decades ago including multiple books to film including sequels. His “The Satan Bug “ was hard sci-fi that came before Michael Creighton and others who wrote about potential pandemics. “Goodbye California “ was another sci-fi thriller that included themes pertaining to now but is rarely heard of .

I just discovered James Clavell co-wrote the screen play for The Satan Bug. Guess which potboiler I am reviewing on Sunday?

I read Hawaii when I was in high school! I remember enjoying it greatly!

Heh, I see that vitruvian and hoopmanjh were born very close in time to one another.

I finally tracked down a list for my birth week.

1. SHIP OF FOOLS, by Katherine Anne Porter

2. DEARLY BELOVED, by Anne Morrow Lindbergh

3. YOUNGBLOOK HAWKE, by Herman Wouk

4. THE REIVERS, by William Faulkner

5. UHURU, by Robert Ruark

6. THE PRIZE, by Irving Wallace

7. ANOTHER COUNTRY, by James Baldwin

8. THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY, by Irving Stone

9. FRANNY AND ZOOEY, by JD Salinger

10. LETTING GO, by Philip Roth

11. PORTRAIT IN BROWNSTONE, by Louis Auchincloss

12. THE BIG LAUGH, by John O’Hara

13. DEVIL WATER, by Any Seton

14. THE BULL FROM THE SEA, by Mary Renault

15. THE GOLDEN RENDEZVOUS, by Alistair MacLean

16. CAPTAIN NEWMAN, M.D., by Leo Calvin Rosten

The only name that’s completely unknown to me is Ruark, though Auchincloss and Seton are really just names I’ve heard with no connection. I’ve read three of the books on the list — Stone, Renault and Salinger (for school) — and 6 or 7 of the other authors, though not the books on this list. That’s not bad, there are some pretty big names for that week.

Mine:

1 THE LAST HURRAH, by Edwin O’Connor. (Little, Brown and Co.)

2 TEN NORTH FREDERICK, by John O’Hara. (Random House.)

3 ANDERSONVILLE, by MacKinlay Kantor. (Cleveland: World Publishing.)

4 AUNTIE MAME, by Patrick Dennis. (Vanguard Press.)

5 THE QUIET AMERICAN, by Graham Greene. (Viking Press.)

6 ISLAND IN THE SUN, by Alec Waugh. (Farrar Straus and Giroux.)

7 MARJORIE MORNINGSTAR, by Herman Wouk. (Doubleday and Company, Inc.)

8 CASH McCALL, by Cameron Hawley. (Houghton and Mifflin.)

9 LUCY CROWN, by Irwin Shaw. (Random House.)

10 BOON ISLAND, by Kenneth Roberts. (Doubleday and Company.)

11 H.M.S. ULYSSES, by Alistair MacLean. (Collins Clear-Type Press.)

12 THE MAN IN THE GRAY FLANNEL SUIT, by Sloan Wilson. (Simon and

Schuster.)

13 NATIVE STONE, by Edwin Gilbert. (Doubleday and Company, Inc.)

14 TENDER VICTORY, by Taylor Caldwell. (McGraw-Hill.)

15 IMPERIAL WOMAN, by Pearl S. Buck. (John Day Company.)

16 HARRY OF MONMOUTH, by A.M. Maughan. (William Sloane.)

I’ve heard of six of them.

Herman Wouk died just this month, at age 103. An author that outlived his audience …

Burying copies (c’mon, you know you wanted to say burn copies) of Ayn Rands works ? Ease up comrade. Funny I never hear or see people wanting to burn copies ofThe Communist Manifesto. Nor should anyone want to, it’s important to learn from our mistakes, especially one that led to the MURDER of tens of millions around the globe. Try to find some joy in this life and have a nice day.

Oh, here we go:

Well, let’s see – I recognize The Godfather, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, and The Andromeda Strain – and I’ve read the last one of the group.

If anyone else is looking, I found my information through http://www.hawes.com/1969/1969.htm – I suspect other years will work in the url as well.

While I appreciate your points, its reality that people only have enough time and/or brain cells to devote to activities like reading. Given that millions of books exist and more are written every day, its a little disingenuous to call people out for not reading the so-called classics. The only reason anyone reads Shakespeare these days is because they had to for lit class. On their own, who would do it?

Sure but at least he did it over a century, rather than having his market suddenly evaporate at age 30. Or, as local used book stores assure me is the case with Tom Clancy, have the market for his books poisoned by subpar collaborations, tie-in products and necrolaborations.

I am not calling people out for not reading classics. I am advising people to come to terms with transience, rather than shouting at kids for liking different stuff than we did, and for not being aware of our old favourites.

There’s another library disappearance option: stolen and not replaced. ISTR Asimov commenting about a librarian having told him that his books were notable for being most frequently stolen.

@21 — Yes, I was noticing that myself. :)

On the other hand, I included the Karres series and the Heinlein juveniles in my daughter’s bedtime reading. I am now informed that I cannot have those books back. :)

Of course, having Dad to annotate the old scientific and cultural references helped.

@25/ragnarredbeard: Some people read classics on their own. Even Shakespeare. And a lot more people read Conan Doyle and Tolkien.

I suspect that I am bit older than most of the respondents. Here is my list:

1 THE PARASITES, by Daphne du Maurier. (Doubleday and Company.)

2 THE EGYPTIAN, by Mika Waltari. (Putnam.)

3 THE KING’S CAVALIER, by Samuel Shellabarger. (Little, Brown and Co.)

4 THE WALL, by John Hersey. (Alfred A. Knopf.)

5 THE HORSE’S MOUTH, by Joyce Cary. (Harper and Brothers.)

6 GENTIAN HILL, by Elizabeth Goudge. (Grosset and Dunlap.)

7 JUBILEE TRAIL, by Gwen Bristow. (Ty Crowell Co.)

8 MARY, by Sholem Asch. (Putnam.)

9 A RAGE TO LIVE, by John O’Hara. (Random House.)

10 ONE ON THE HOUSE, by Mary Lasswell. (Houghton Mifflin.)

11 THE PINK HOUSE, by Nelia Gardner White. (Viking Press.)

12 THE DIPLOMAT, by James Aldridge. (Little, Brown and Company.)

13 I, MY ANCESTOR, by Nancy Wilson Ross. (Random House.)

14 THE STRANGE LAND, by Ned Calmer. (Charles Scribner’s Sons.)

15 A LONG DAY’S DYING, by Frederick Buechner. (Alfred A. Knopf.)

16 MINGO DABNEY, by James H. Street. (Dial Press.)

I don’t recognize any of the titles and only recognize 2 authors (Daphne du Maurier & John Hersey)

@32 — I own the film version of The Egyptian but I haven’t read the book (mostly because it doesn’t seem to be available on Kindle yet).

@11

Libraries are constantly culling books to make room for other books. Any book, no matter how classic, will get tossed to make room for the newest buys if no one has checked it out in recent years. A hard truth but a truth, nevertheless.

“One of the nastier trends in library management in recent years is the notion that libraries should be “responsive to their patrons.” This means having dozens of copies of The Bridges of Madison County and Danielle Steele, and a consequent shortage of shelf space, to cope with which librarians have taken to purging books that haven’t been checked out lately.”

― Connie Willis, Bellwether

I was also mostly struck by the Michener not being available. Then again, I seem to be very nearly exactly James’ age.

Harlan Ellison used to have a great talk about how entire genres disappeared, even from memory. He referenced the “Scandal Novel” genre, popular at the turn of the previous century as an example.

“The author could die without a proper will, leaving their work in the hands of people actively hostile to their career.“

and the footnote:

“Or the inheritors of the copyrights may be so convinced in the value of the late author’s work that they price it right out of the market.”

Would you mind providing some examples? I’m curious…thanks!

@34/escaape: My local library sells all the books that are older than ten years or so. I used to find rare and weird old books in libraries when I was young, books I never would have encountered in any bookstore. This can’t happen anymore.

@23 Nah, bury. Ayn Rand’s books will make good fertiliser for the same reason you can’t set them on fire. Shite disnae burn.

@36:

1. John M. Ford.

2. Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore.

After going and looking at the lists for my kids’ birthdays, I think these 50-60 year old lists may be somewhat skewed by their methodology. Most of the lists here are showing primarily mainstream fiction, honest-to-goodness lit’rachoor, with the occasional absolutely massive seller like MacLean. Later lists start showing mysteries and thrillers, then horror and ultimately even SF. IRRC, back in the day the NYT would just call all the bookstores in NYC and ask what was selling, rather than actually tracking sales. Were more people really buying the most recent work by James Baldwin than the latest John Dickson Carr, Nero Wolfe or Perry Mason? I suspect some pretty strong reporting bias.

None of which in any way shakes James’ thesis. In fact, that might even strengthen it. Major literary names like Baldwin, Wouk or Roth are probably actually more likely to be known and still around than the highly commercial mysteries I mentioned above.

@32,

I can recommend Mary Lasswell- funny and sweet. They are available in e-book.

I too was born in the year of Hawaii.

When I started out as librarian, I was shocked at how many books in a typical library have not been checked out in years, or may not have been checked out ever. That’s why we weed collections. Keeping a years-old title that no one checks out on the shelf in hopes that someone might read it in five or ten years is a sunk cost fallacy.

Couldn’t find a list from the week I was born, but these are the bestsellers from the year:

LOVE STORY by Erich Segal

THE FRENCH LIEUTENANT’S WOMAN by John Fowles

ISLANDS IN THE STREAM by Ernest Hemingway

GREAT LION OF GOD Taylor Caldwell

QB VII by Leon Uris

THE GANG THAT COULDN’T SHOOT STRAIGHT by Jimmy Breslin

THE SECRET WOMAN by Victoria Holt

TRAVELS WITH MY AUNT by Graham Greene

RICH MAN POOR MAN by Irwin Shaw

I’d heard of all these authors, but then again I sold used books for a living for 17+ years. Hemingway, I presume, is the only household name, though I’d guess most literate people would know Fowles and Greene.

1 PEYTON PLACE, by Grace Metalious. (Simon and Schuster, Inc.)

2 LETTER FROM PEKING, by Pearl S. Buck. (John Day Company.)

3 COMPULSION, by Meyer Levin. (Simon and Schuster.)

4 SILVER SPOON, by Edwin Gilbert. (Lippencott.)

5 THE SCAPEGOAT, by Daphne du Maurier. (Doubleday and Co.)

6 THE WORLD OF SUZIE WONG, by Richard Mason. (World Publishing Co.)

7 THE PINK HOTEL, by Dorothy Erskine and Patrick Dennis. (G. P. Putnam’s

Sons.)

8 ON THE BEACH, by Nevil Shute. (William Morrow and Company.)

9 THE LAST ANGRY MAN, by Gerald Green. (Charles Scribner’s Sons.)

10 BLUE CAMELLIA, by Frances Parkinson Keyes. (Julian Messner Inc.)

11 LIFE AT HAPPY KNOLL, by John P. Marquand. (Little, Brown, and Co.)

12 THE DURABLE FIRE, by Howard Swiggett. (Houghton Mifflin Co.)

13 THE WONDERFUL O., by James Thurber. (Simon and Schuster.)

14 A HOUSEFUL OF LOVE, by Marjorie Housepian. (Random House.)

15 THE SHORT REIGN OF PIPPIN IV, by John Steinbeck. (Viking.)

16 THE LADY, by Conrad Richter. (Alfred A. Knopf.)

Of these, Peyton Place (by title/theme) seems to be enduring, and On The Beach probably qualifies as a true classic (personally, I like several of the author’s other books better).

From the ones others have listed earlier, In This House of Brede by Rumer Godden is one of my top 10 favorite books of all times. I am still fond of Elizabeth Goudge but there’s a fair amount of sentimentality plus some pretty sexist assumptions. And Michener, Leon Uris, and Dick Francis were among the authors I read as I transitioned from the children’s section to the adult section of the library in those pre-YA days.

jmeltzer @22 had Auntie Mame by Patrick Dennis on his list. That’s one where the book may not often be read any more, but the stage musical and movies based on it are probably familiar. (“Life is a banquet, and most poor fools are starving to death!” which I believe was most poor bastards in the original.)

Re the original point, times change and things fade away. The things that affected us live on in what we make of them. It doesn’t mean that others coming behind us need to have the same influences.

I wonder if this isn’t due to copyright laws, which became longer as time passed due to corporate pressure (hello, Dysney!). Some stuff that was popular at the turn of the century somehow remained kind of popular 100 years later, and I’m talking about stuff that wasn’t considered high-class literature. “Tarzan”, “The Three Musketeers”, “Zorro”, “The Phantom of the Opera”, “Dracula” weren’t considered masterpieces of literature 100 or 150 years ago. They kind of remained in popular consciousness due to new adaptations (movies, TV series, radio dramas, musicals, etc). I wonder if the added cost of copyright didn’t stifle the stories that came after the 1930s from being adapted more often.

Also, another book that was never adapted until 100 years later, but kind of remained popular among SF fans was “A princess of Mars”, which is being talked about in another article on Tor today. In this case this remained true because the book was handled from one generation of fan to another.

That may contribute but I remember as a teen I was pretty meh on books older sf fans loved. Lensman was pretty clunky, for example, and most Van Vogt beyond tedious.

@25. I read Shakespeare when I was in middle school and onward. Mark Twain in elementary school. I was almost tossed out of the library because I was laughing so hard at the drunk scene in ROUGHING IT. But I was that kind of person.

I also remember almost every author listed here.

@36 From personal experience, one of my best writing friends died of fast-moving cancer while her bestselling career was in full bloom. From stupidity and disinterest, her red neck husband closed down all her promotion sites and fired her agent. Those of us who loved her and knew that she considered her last book her best book went all out to promote it in her honor. The moral of this story is to have someone who understands your writing career as your literary executor.

@40 It’s not methodology. The obsession with genre in publishing and bookstores wasn’t really a thing during the time of these early lists. Books of all kinds were stacked together and not segregated by genre. Almost every type of hardcover book was considered what we now call “mainstream.” Most were handsold by clerks. My own guess would be the rise of big box bookstores like B&N and the volume of types of books sold made genre and segregated bookshelves more important.

I like my list! Lots on there I recognise and quite SF-heavy.

I’ve been amused by some of the lists which have authors I really don’t mentally categorise as being in the same era snuggled together as contemporaries.

1 LAKE WOBEGON DAYS, by Garrison Keillor.

2 THE MAMMOTH HUNTERS, by Jean M. Auel.

3 TEXAS, by James A. Michener.

4 CONTACT, by Carl Sagan.

5 SECRETS, by Danielle Steel.

6 GALAPAGOS, by Kurt Vonnegut.

7 THE POLAR EXPRESS, written and illustrated by Chris Van Allsburg.

8 SKELETON CREW, by Stephen King.

9 THE CAT WHO WALKS THROUGH WALLS, by Robert A. Heinlein.

10 THE SECRETS OF HARRY BRIGHT, by Joseph Wambaugh.

11 THE ACCIDENTAL TOURIST, by Anne Tyler.

12 WORLD’S FAIR, by E. L. Doctorow.

13 WHAT’S BRED IN THE BONE, by Robertson Davies.

14 LONDON MATCH, by Len Deighton.

15 LUCKY, by Jackie Collins.

The list for my birth week includes a Kenneth Roberts book that I’ve never heard of, “Boon Island”. He’s another author rarely read now. My three local libraries have “Arundel”. Two have “Northwest Passage”. Only one has “Rabble in Arms”.

It is interesting to look at the Goodreads list for 1956, which includes more than mainstream hardcover fiction. A few examples:

* The Last Battle, C. S. Lewis

* Howl and other Poems, Ginsberg

* The Fall, Camus

* Old Yeller, Fred Gipson

* Harry the Dirty Dog, Gene Zion

* The 101 Dalmations, Dodie Smith

* Double Star, Heinlein

* The Death of Grass, John Christopher

* The Big Red Barn, Margaret Wise Brown

https://www.goodreads.com/book/popular_by_date/1956

Hogwash. There is much excellent SF being written today. Either you’re not looking hard enough, or you’re stuck in a rut, expecting everything to read like Asimov and Clarke.

Few things are outdated so quickly as visions of the future, so I suppose SF may have a shorter half-life than other genres.

I am sceptical about “values dissonance” being a big issue. Tolkien was considered a Conservative in the 1950s, and he is still read. Jane Austen was apparently conservative in 1815, and she is still read. OTOH, Charles Dickens and HG Wells were certainly not conservatives. And are still read. Changes in values do not seem to make much difference.

For that matter, in her autobiography Ayaan Hirsi Ali wrote about happily reading Wuthering Heights, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and other western books in East Africa. Plenty of values dissonance between Danielle Steele and Somalia. Frankly, I think it absurd to suggest there are bigger values differences between 1980s America and 2010s America, than there were between 1980s America and 1980s Somalia.

On the other hand, fashions can change as quickly as the future, so changes in fashion can probably be important. Works that are praised as with-it, and in the moment, probably go out of the moment first.

Overpopulation was a big issue when Larry Niven was writing about it, and organ transplants new when he was writing about organleggers. Not so much now.

Before downloadable e-books, work was on sale as long as it sold in sufficient quantity,and then “out of print”. Maybe brought back when sales were expected again for various reasons. Nowadays there’s no need for a book to be unavailable – though it can be – although still books that aren’t the latest get less attention, and less… We can look to reviewers (ahem) to compare new books to the old good stuff that influences them… or, not so good.

I’m suspecting that this time, the throwability of a novel by Michener is hypothetical and not the basis of an anecdote – and yet you have lived such a rich life…

Winnie Ille Pu is still in print, at least, and unlikely to be unavailable soon. It’s frequently given as a gift to students taking Latin. Hard to say how often it’s actually read–which is too bad, since in its own way it’s a work of genius.

Michener’s Hawaii still seems to be in print, too, which surprises me a little.

But: all culture is mortal, and sf/f is culture, therefore it’s mortal.

Trying to get young people interested in writers who’ve been dead for a thousand or two thousand years is my day job, so I don’t have too many tears to shed on the grave of Doc Smith. But I’m pretty sure people will be reading work by Le Guin or Dunsany, for instance, in the next century. If I’m wrong… well, it’s statistically unlikely that I’ll be around to care about that.

Was just thinking to myself a couple of days ago how Michener has dropped out of the literary conversation. Even his suitable-for-household-defense Space, which is arguably SF. Never mind otbe’d books like The Covenant. Both of which I have in hardcover, neither of which I’ve read in years.

Leon Uris was massively popular in the 70’s and almost unknown today. He wrote the only novel I know of that is set in the Berlin Airlift.

One of the problems with Tom Clancy’s work is that after his third or fourth novel he desperately needed a good editor. Someone who could go through and delete multiple side-plots and a few hundred pages.

I seem to also be quite close to vitruvian and hoopmanjh’s age, perhaps a few months younger.

AIRPORT, by Arthur Hailey.

COUPLES, by John Updike.

MYRA BRECKINRIDGE, by Gore Vidal.

VANISHED, by Fletcher Knebel.

THE TOWER OF BABEL, by Morris West.

CHRISTY, by Catherine Marshall.

TOPAZ, by Leon Uris.

TUNC, by Lawrence Durrell.

THE CONFESSIONS OF NAT TURNER, by William Styron.

THE TRIUMPH, by John Kenneth Galbraith.

I recognize three of the titles, seven of the authors.

Connie Willis also addressed libraries triaging books in her novella from last year I Met a traveler in an Antique Land (Subterranean Press, stocked by my library). I’ve heard of 9 out of your 15, and have read 2 of them, but I’m older than you are and not a valid test. My 1948 list also has a Keyes novel: Dinner at Antoine’s.

One of the other inevitable trends is the reprint of forgotten-by-most-people work. New York Review of Books has an ongoing series of several hundred novels, memoirs, histories from English language authors and from other-language authors with translation for this series.

In the SF publishing world, some small presses are re-publishing forgotten books. Aqueduct Press has brought out several interesting older works in dead-tree form as well as Epub formats. This includes a perennial favorite of mine, Ring of Swords, by Eleanor Arnason.

There is a need for regional library systems with inter-library loan. A given small town library may not be able to stock all worthy older “genre” novels. A county, regional, or small state consortium can have an amazing catalogue rivaling major city libraries.

I looked forward to putting the beloved books of my childhood into the hands of my own children. But they didn’t care to read my treasures; they had their own beloved books. So it goes.

The province in which I live just killed interlibrary loans.

Reading these comments brought up a flood of memories of my life with books. I was born in 1958 and grew up being the big reader of the family (dad, mom and sis were not readers). I used to go on weekly trips with my grandmother to her neighborhood library, where she would go into the adults room and I would spend my time in the children’s wing, looking through all sorts of books on science and space (my grandmother also bought me my first comic book, which started another lifetime love). When our family moved to the next town over, I started going to the library there, where, with the use of my father’s adult card, quickly discovered 1960s and earlier science fiction (mostly Doubleday Science Fiction books, anyone remember those?), until I was able to get an adult card in 8th grade. I would go shopping to strip malls with my parents and run into various bookstores (some of which had long aisles of magazines—where I saw my first Galaxy and Analogs) and spend hours there while my parents shopped elsewhere (remember books @16/17, @24 and @43).

The 1970s gave me the opportunity to get after-school jobs that fed my eventual book buying habit—all the SF magazines at times, and I would go to bookstores on my own, not only looking at SF, but mainstream books—many of the lists others have posted have titles that were familiar to me from back then. Eventually I got a job when I was in high school at the library, where I had the freedom to look at all the books anywhere in the building (including the basement, where stacks of uncatalogued books from the turn of the century were housed for unknown reasons—I used to look at a set of the original first generation Tom Swift books, lusting for them). I helped run summer book sales, where I put out many of the old, donated books, some bestsellers mentioned by others above, for 25 or 50 cents each. Had first dibs on some Winston and Gnome Press SF hardcovers, which I still own.

There was another library in a suburb of our town, semi-private and built in 1894, which I had a card, and where you could go in and find (and check out) original Verne, Wells and Burroughs novels in hardcover, as well as many mainstream novels, that dated back into the late 1800s. The library had a fireplace they used in the winter, and most of the stacks were on two floors, one intricately tiled, and the upper floor being opaque glass that glowed with the fluorescent lights from the main floor.

In college, I worked two years part time in the tallest library in the world and expanded my view of novels internationally (it also helped with being in a college area loaded with bookstores of all types). Weekend trips with college friends to Boston exposed me to the British publishing market, and soon was able to supplement my SF collection with items out-of-print in the US, or books by British authors I only heard about but never saw. I eventually transferred to another school with a world-renowned university also in town after two years, and again was in an area with a multitude of bookstores. I started working part-time for Waldenbooks in 1980, which eventually turned into an 8-year career (selling the books at @9 to people—I feel old!). After that, co-owned a comic bookstore for a few years, then worked a few months at the Yale Co-Op (where I helped on trips to purchase used and rare books for sale at the store), then headhunted by a local book wholesaler / distributor (now sadly gone). In the mid-90s, I changed careers entirely (where I still am today), but my love for books and bookstores in general has not gone away. Whenever I travel, I plan time in bookstores, even if I can’t read the language. I plan annual trips to Toronto, which is a great place to find both US as well as British books (good place to get SF Masterworks books from Gollancz, many of which are out of print in the states). I’ll love books and bookstores until the day I die, and I hope that nothing will take away the many happy memories I have of time spent with books.

Maybe this is part of why I haunt* used bookstores. In light of this discussion, used bookstores may be one of the great keepers of memory in this civilization. For sci-fi, nothing in my part of the world beats Uncle Hugo’s in Minneapolis.

*Hmm, now there’s a felicitous word choice.

We have a shocking number of people who haven’t read a book since they had a teacher tell them it was required reading. Problem number one.

Film and video have become the default storytelling medium. Problem number two.

“The Princess Bride” is one of my favorite films. Very funny, well-made , and a brilliant soundtrack, thanks to, mostly, Mark Knopfler, but, when I tell others, often fans of the movie, to read the book because it’s even funnier, the usual response is “it’s a book?”

Sermons and Soda-Water is actually not a novel, but rather three novellas. I got rid of my copy recently; I didn’t think that book was the equal of O’Hara’s story collections published from 1960 to 1968, which were also big sellers at the time (as hardcovers and also as Bantam paperbacks; I have all of the latter, from Assembly through And Other Stories). In my opinion the stories are what he’ll be remembered for, not the novels.

@21: Ruark is thoroughly forgettable; his deep-south masculinism would probably grate these days. I know him because my grandfather (b. 1890) gave me a fixup-of-columns called The Old Man and the Boy because arthritis prevented him from teaching me to hunt.

@36: also, (2) Clifford Simak (at least initially; some bits came out after my group gave up.)

@42: did your library not have off-site archives? I know Boston’s does — a good thing, as the recent main-building rebuild seems to me to have substantially reduced the space for fiction. OTOH, they seem to be culling even the archives — I’d swear there were fewer Hugh Walters books (a genre favorite when I was ~10) the second time I looked.

@60: how very shortsighted of them.

@61: Wonderful memories! I survived 3 years in a small town by being within reach of a wonderful old block of a building — it always struck me as wanting bats flying out of the attic even if it didn’t look at all like the Addams manse.

My list:

DESIREE, by Annemarie Selinko. (William Morrow.)

BATTLE CRY, by Leon Uris. (G.P. Putnam’s Sons.)

THE DARK ANGEL, by Mika Waltari. (Putnam.)

THE HIGH AND THE MIGHTY, by Ernest K. Gann. (William Sloane Associates.)

THE SILVER CHALICE, by Thomas B. Costain. (Doubleday and Company, Inc.)

KINGFISHERS CATCH FIRE, by Rumer Godden. (Viking.)

THE EMPEROR’S LADY, by F.W. Kenyon. (Thomas Y. Crowell Company.)

KISS ME AGAIN, STRANGER, by Daphne du Maurier. (Doubleday and Company, Inc.)

THE ECHOING GROVE, by Rosamond Lehmann. (Harcourt, Brace and Co.)

GOLDEN ADMIRAL, by Francis Van Wyck Mason. (Doubleday.)

HOTEL TALLYRAND, by Paul Hyde Bonner. (Charles Scribner’s.)

THE CAINE MUTINY, by Herman Wouk. (Doubleday.)

ZORBA THE GREEK, by Nikos Kazantzakis. (Simon and Schuster.)

NINE STORIES, by J.D. Salinger. (Little, Brown and Company.)

IN THE WET, by Nevil Shute. (William Morrow and Company.)

STEAMBOAT GOTHIC, by Frances Parkinson Keyes. (Julian Messner, Inc.)

I recognize ~half of the authors but just two of the titles — and those two are the ones made into movies.

I CAPTURE THE CASTLE by Dodie Smith

THE PURSUIT OF GOD: by A.W. Tozer

BLUEBERRIES FOR SAL by Robert McCloskey

THE LOTTERY by Shirley Jackson

THE NAKED AND THE DEAD by Normal Mailer

EL TUNEL by Ernesto Sabato

CHEAPER BY THE DOZEN by Frank B. Gilbreth Jr.

MY FATHER’S DRAGON by Ruth Stiles Gannett

THE HEART OF THE MATTER by Graham Greene

NO LONGER HUMANA By Osamu Dazai

KON-TIKI by Thor Heyerdahl

KING OF THE WIND by Marguerite Henry

THE THREE LITTLE PIGS by Al Dempster

THE SEVEN STORY MOUNTAIN by Thomas Merton

TAKEN AT THE FLOOD by Agatha Christie

I grew up during the Paperback Revolution. It was hungry for content. Including that crazy science fiction stuff. Most of the good stuff from the pulps got reprinted. Anthologies from Weird Tales and Astounding, collections of Doc Smith and Heinlein and Kuttner. Vern and Wells, Frankenstein and Dracula, the Foundation and the Weapon Shops, on and on.

It was possible to know most of the Science Fiction and Fantasy field, and to keep up with new stories and novels. That continued to be true through the Sixties, if you subscribed to enough magazines. When the Hugo nominations came out, most fen had read most of the books.

In the Seventies the pace of publication sped up. It got harder and harder to keep up with everything. By the eighties it was impossible. There were too many books, in a mare’s nest of categories. Not only were there more books. The books got longer, and traveled in gangs of three or four or six. By now it’s hard for someone who specializes in, say—military SF—to keep up within that sub-field.

It’s not just the passage of time, or changes in cultural assumptions, that drowns out old classics. It is the sheer volume of stories and books and series. Nobody can keep track of what is being published this year, let alone grasping the history of the genera.

@65 Chip: I think you and I must be about the same age, if that’s your birth year list. I’ve actually read 5 or 6 of those. My eye was caught by James’s list at the top because The Last of the Just is one of the greatest books I ever read and it makes me sad that it’s forgotten. Some of the other authors mentioned — Leon Uris, Daphne Du Maurier, Michener, Thomas Costain, Rumer Godden, Frances Parkinson Keyes — bring back memories of happy afternoons in the Carnegie Library, which in my teens was falling apart and was eventually replaced by a new modern building. I wouldn’t dare predict what authors will survive; I would HOPE LeGuin and Daniel Abraham, but who knows?

@25/ragnarredbeard,

I read Hamlet on my own after seeing the Mel Gibson movie of it. And I read Macbeth after seeing a performance of it on PBS. No Shakespeare in high school!

I had a high school English class in which we read A Tale of Two Cities, but after reading a few pages I decided to just read the Cliff Notes. Having in adulthood learned something about the French Revolution – motivated by a desire to find out something about the times in which the chemist Lavoisier lived – I have become somewhat interested in A Tale of Two Cities now, although I would probably opt for the audiobook.

In other words, the classics are just books like any other. If they sound interesting, I’ll read them, or at least give them a chance.

By the way, my public library does not have copies of Mote in God’s Eye, Stand on Zanzibar, Caves of Steel/ Naked Sun/Robots of Dawn/Robots and Empire, Simak’s City, or of course that admittedly nostalgic favorite of mine Empire of the Atom (Van Vogt).

Let’s face it: Amazon has become a better place to find things than the local library, using the logic of “Readers who purchased this also purchased these” to make recommendations. On the plus side, being able to offer these things on Kindle should mean there’s not much reason for anything to be “out of print”.

@67,

I would try The Last of the Just, but not for $12.97 on Kindle. Time to try my University library.

Saul Bellow, not Bellows. Apparently even he isn’t that well remembered.

@66/Fernhunter: The sheer volume of new stories and books is actually one of the reasons why I read classics. Classics have already stood the test of time. I usually turn to a classic after a disappointing new book, or if I don’t know what I want to read next.

@68/Beta: I read Macbeth for the first time a couple of weeks ago. It was the best book I read this spring.

thanks for this excellent post! Sadly, books do die. (I had thought they were immortal.) I regularly cull my own shelves to make room for new arrivals, and have seen many literary fashions come and go in the donations to the charity book sale that I run. When the fever breaks, suddenly everyone’s giving you books by Dan Brown, for example. And thank God for Project Gutenberg and all the other free ebooks floating around, as they enable one to get older and more obscure items. I got the (nearly) complete works of Charlotte Perkins Gilman as an ebook that cost $1!

@25

who reads Shakespeare? I have, since I fell in love with Midsummer Night’s Dream in the 7th grade. Better yet, I see the plays as often as I can, since that’s why Shakespeare wrote them. One of Shakespeare’s advantages, however, is his medium. Plays are far more open and adaptable than novels, so good ones are easily updated in staging, as well as adapted. Adaptations, however, age faster than the originals (See Nahum Tate’s adaptation of King Lear, which has a happy ending (!), was wildly popular in its day and is now read mainly for laughs).

@51

Values dissonance certainly affects book survival, but is less important for better written work. And I think your example of Jane Austen is weaker than you think. Yes, circumstances have changed a lot, but people still want to read books that are about women searching for lives of integrity, exciting to read and very funny. But values dissonance is finally taking a toll even on Shakespeare. The Taming of the Shrew and Merchant of Venice have gone from being 2 of his most popular comedies to being performed much less often and less confidently. Shrew, because watching men breaking a woman is less amusing today, to put it mildly, and Merchant, because forcing somebody to change their religion upon threat of death is much harder to sell now as “Christian mercy”. Also, the Holocaust isn’t Shakespeare’s fault, but today’s readers and audiences have to deal with it in dealing with the play.

@72 Msb: It’s true that The Taming of the Shrew can be played to emphasize the “breaking” of Kate, but I think Shakespeare — allowing for the general sexism of his culture and time — is actually doing something a bit different. Kate starts out as a very unpleasant person to be around. Sure, she’s justifiably angry at the world for the position she’s in and the lack of respect she gets, but she’s mean and nasty to her sister, sour and bad-tempered to everyone else, destructive and self-righteous and sneering. Being justifiably angry doesn’t justify taking out your anger on all and sundry. What Petruchio does on their wedding day and night is turn the tables on her: he puts her in the same position as everyone who’s had to deal with her, to show her what it’s like to be on the receiving end of all that bad temper — so that she finally understands that’s not the kind of person she wants to be. In a sense, he frees her from her black hole of rage. I’ve seen more than one production of the play that brings this out and I think it’s a mistake to just assume it’s misogynistic.

What are some of the more notable cases of Footnote 2- where the heirs of an author’s body of work price it out of circulation?

Just asking bookstores what was selling would have missed things, in the days when most drugstores and gas stations had racks of paperback fiction, and significant amounts of sf (and I think other genres) started in paperback and were distributed largely through those channels. The bookstores might have been accurately reporting what they sold, and still produced a limited and biased sample, like the famous 1948 presidential polls that only reached voters with home telephones.

That doesn’t mean there wasn’t also a (perhaps deliberate, perhaps not) tendency for bookstores to report the books they thought were important, or the ones the store owner thought people should be reading.

For people with a disposable income.

I’m not sure if it’s an example of footnote #2, but I’m still kind of amazed that Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., which was set up by ERB’s estate specifically to manage his intellectual property, doesn’t seem to have any interest in keeping his books in print in approved editions, although on Kindle you can find great stacks of dubiously-sourced editions of everything that’s fallen into the public domain (and some that might actually not be public domain, at least in this country).

In Olden Times, the Burroughs Estate was famous for the diligence with which it pursued perceived IP transgressions. As I recall, Charles Saunders’ Imaro had its first print run pulped because Burroughs Estate objected to the cover blurb describing the protagonist as a black Tarzan.

Ya’all got me curious…

1 THE SHOES OF THE FISHERMAN, by Morris L. West.

2 CARAVANS, by James Michener.

3 THE GROUP, by Mary McCarthy.

4 ELIZABETH APPLETON, by John O’Hara.

5 CITY OF NIGHT, by John Rechy.

6 JOY IN THE MORNING, by Betty Smith.

7 THE COLLECTOR, by John Fowles.

8 ON HER MAJESTY’S SECRET SERVICE, by Ian Fleming.

9 THE CONCUBINE, by Nora Lofts.

10 POWERS OF ATTORNEY, by Louis Auchincloss.

I’ve read 4 of these and heard of two others. While I imagine the Flemming and Michener would be remembered (West, not so much), Fowles first novel is easily the greatest book on this list. Interesting.

My list for the week I was born.

1 THE PASSIONS OF THE MIND, by Irving Stone. (Doubleday and Company.) 1 12 2 QB VII, by Leon Uris. (Doubleday & Company, Inc.) 2 28 3 THE NEW CENTURIONS, by Joseph Wambaugh. (Little, Brown and Company.) 3 17 4 THE UNDERGROUND MAN, by Ross Macdonald. (Random House.) 4 14 5 THE BELL JAR, by Sylvia Plath. (Harper and Row.) 8 6 6 THE THRONE OF SATURN, by Allen Drury. (Doubleday.) 5 15 7 THE ANTAGONISTS, by Ernest K. Gann. (Simon and Schuster.) 7 14 8 BIRDS OF AMERICA, by Mary McCarthy. (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.) — 1 9 LOVE IN THE RUINS, by Walker Percy. (Farrar Straus Giroux.) 9 2 10 SUMMER OF ’42, by Herman Raucher. (G. P. Putnam’s Sons.)

I recognize 6 authors and read two but other works. The Bell Jar I’ve just skimmed but seems to be the most enduring title from my list. Weeding books is hard but it has to be done unless the building just keeps getting bigger.

@73 Tehanu (love your nym – one of my favorite books)

i’ve seen a lot of productions take the line you suggest, but it requires playing against the text, which makes clear that:

(1) Petruchio marries Katherine for her money

(2) his “training” consists of depriving her of food, sleep and clothes, which are torture techniques, not to mention changing her very name, and

(3) Petruchio wins a bet made with the other men in the play by getting Katherine to denounce the disobedient other women and declare her utter subservience to her “lord and master”.

very successful productions have followed this line, but they are declining in number, and I don’t find them convincing. YMMV, of course.

I will see a gender-switched production this summer, which sounds interesting, but I don’t know what it will prove. If you ever have the chance, see Fletcher’s sequel to Shrew, which is called The Tamer Tamed. The RSC staged it as a pair with Shrew some years ago, and the paring was very thought provoking.

@81/Msb: Have any productions played it as a tragedy?

@78 — I wouldn’t be surprised if they’re still doing everything they can to squelch the genuine infringements (I know I have a couple of things on my Kindle where the sale pages have since disappeared), but I assume it’s like going after cockroaches; I’m more puzzled that they don’t seem to have a lot of interest in keeping his original works available — the ERB website has synopses of the original books, but the only things they’re currently selling seem to be modern pastiche/continuations (and one or two very expensive limited editions of the originals). I’d be happy to be proven wrong …

I wonder how many of the original books are public domain now.

@76,

True. I happen to also be in favor of UBI.

At least in the US, it looks like public domain used to cut off at 1923, but they’ve finally started pushing the clock forward. That makes sense — most of the Barsoom collections I see cut off with Chessmen of Mars (1922), but I do see a few eBook editions of the next two or three books in the series — I assume they’re being sourced from someplace with a more recent cut-off date and/or that they’re the sorts of listings that’ll go away when the ERB estate notices them and brings the hammer down. For Tarzan it looks like the cut-off is somewhere around Tarzan and the Ant-Men (#10), so that’s less than half of the series. And most or all of Pellucidar and Venus is still off-bounds, at least based on a quick check of publication dates.

I suspect some books are kept in print only because they’re common required reading in high school, with the other edge of that blade being that many people will never read anything by that author again.

@82 Jana Jansen

i saw one in the 1990s which expanded the induction, about Christopher Sly, to make the play a kind of revenge fantasy for him. It worked but was awfully sad. The last RSC production before this year’s was successful, largely because the leads played it as Love at first sight, but a friend of mine accurately called it “a nasty production of a nasty play”. And of course we don’t have any closing framing that Shakespeare might originally have written. This is one of the problems with the Folio, which was published 7 years after Shakespeare’s death.

I believe the play would work better if it weren’t such an early work, which leans too heavily on contemporary ideas of and jokes about how to deal with a “scold” (I.e. “uppity woman”). Shakespeare did much more justice to his female protagonists in his later work. If you know his other comedies, there are several places in Shrew where you turn to Katherine and expect her to speak up for herself like Beatrice or Isabella or Helena, but she is weirdly silent.

I may have read as many as three of those books: Hawaii, Winnie the Pooh (I read it in the original English, to my children), and possibly To Kill a Mockingbird (if I did, it was required reading in high school; I’ve reread absolutely none of my high school required reading).

On the other hand, I have read literary fiction that was nowhere near my HS English classes.

This is why used book stores are such a treasure. I’m on a quest to collect all Michener’s books. Even though my husband says I have to dump most of my library so we don’t have to haul it all the way across the country when we move, I’m fighting tooth and nail. I’ve been building my collection for 40 years. I’ll part with the non great authors, the others, never.

http://awfullibrarybooks.net – by librarians from all over, featuring titles found and removed at collection-weeding time. I haven’t been following it so much lately.

I’ve no idea where I’d find a list of books that were bestsellers the week I was born, though the year is pretty easy.

92: Try here.

1. CHESAPEAKE, by James A. Michener

2. WAR AND REMEMBRANCE, by Herman Wouk

3. FOOLS DIE, by Mario Puzo

4. SECOND GENERATION, by Howard Fast

5. THE SILMARILLION, by J.R.R. Tolkien (Middle Earth in pre-Hobbit days)

6. THE FAR PAVILIONS, by M.M. Kaye

7. EVERGREEN, by Belva Plain

8. THE STORIES OF JOHN CHEEVER, by John Cheever

9. BRIGHT FLOWS THE RIVER, by Taylor Caldwell

10. ILLUSIONS, by Richard Bach

11. THE COUP, by John Updike

12. WIFEY, by Judy Blume

13. PRELUDE TO TERROR, by Helen MacInnes

14. EYE OF THE NEEDLE, by Ken Follett

15. THE STAND, by Stephen King

The Silmarillion – on the NYT list two years after release – and The Stand are the two genre books that stand out there.

@40 & @47: Actually, The New York Times Bestseller list (which is what Hawes is archiving) is not statistically sound methodology:

Source: https://www.nationalreview.com/2018/04/new-york-times-bestseller-list-biased-book-news/ . While this source clearly has an ax to grind, I can easily believe the NYT Bestseller List is biased.

Mine:

1 JONATHAN LIVINGSTON SEAGULL, by Richard Bach. (Macmillan Publishing Company.) 1 14

2 THE WINDS OF WAR, by Herman Wouk. (Little, Brown.) 2 37

3 THE WORD, by Irving Wallace. (Simon and Schuster.) 3 20

4 MY NAME IS ASHER LEV, by Chaim Potok. (Alfred A. Knopf.)4 13

5 THE TERMINAL MAN, by Michael Crichton. (Alfred A. Knopf.) 6 12

6 A PORTION FOR FOXES, by Jane McIlvaine McClary. (Simon & Schuster.) 7 9

7 CAPTAINS AND THE KINGS, by Taylor Caldwell. (Doubleday.) 5 15

8 DARK HORSE, by Fletcher Knebel. (Doubleday and Company, Inc.) 8 4

9 THE LEVANTER, by Eric Ambler. (G. K. Hall.) 9 3

10 THE OPTIMIST’S DAUGHTER, by Eudora Welty. (Random House.) 10 5

I’ve read the first two but none of the others although I’ve read other novels by Michael Crichton. And by the way @24, The House on the Strand by Daphne Du Maurier has a time travel plot/romance plot-very different from her other novels, but written so well, that I go back and re read it whenever I re-read Rebecca. That book has stood the test of time……published 81 years ago!

@88, Being acquainted with earlier versions of the Shrew story I notice that Katherine argues that women should obey their men because those men love and care about them not just because women are inferior which is a twist apparently original to Shakespeare. Also Katherine isn’t just an uppity woman but and angry and unhappy one spreading the unhappiness around, and Shakespeare gives her good reasons for that unhappiness. It’s not just modern audiences who see her father plays favorites and Bianca is a passive aggressive little B—-.

All that said it is a work very much of it’s time I can make allowances but apparently many cannot.

There was a question going around social media a few years ago “Who was Roger Martin du Gard? Answer below the cut.” The answer was “He was the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature the year H. P. Lovecraft died.”

And since you mentioned Michener, I once read a quote from him about his favourite fan letter. It was from a cop who’d had his life saved by a paperback of Centennial he had inside his jacket. He said the bullet didn’t make it past the second chapter.

NYT Top 10 for the week I was born:

Centennial – James Michener

The Moneychangers – Arthur Hailey

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution – edited by Nicholas Meyer

The Promise of Joy – Allen Drury

Lady – Thomas Tryon

Black Sunday – Thomas Harris

Something Happened – Joseph Heller

The Dreadful Lemon Sky – John D. MacDonald

A Month of Sundays – John Updike

The Pirate – Harold Robbins

Seven of those author names look, at least, vaguely familiar. None of the titles do. I’ve only read anything by one of those authors. (I’m kind of curious about The Dreadful Lemon Sky now though.)

@99,

The Dreadful Lemon Sky is one of MacDonald’s Travis McGee books. They are definitely good reads. I’ve heard of eight of those authors. I’ll bet the Seven Per-cent Solution is Sherlockania

@100/swampyankee: Yep. In it Sherlock Holmes falsely believes Moriarty to be a criminal due to his cocaine addiction, and is healed by Sigmund Freud.

Pearl S Buck mentioned in a couple of the lists won a Nobel too, yet I’ve never met anyone else who has read anything by her. Very much of her time, but if you are interested in that time worth reading. I used to use a library that had a lot of work published by women in the twenties and thirties, but overall not an extensive collection, so I ended up reading some of them for want of anything else I hadn’t read that looked remotely interesting.

@102/Jazzlet: I read a short children’s book by her, The Dragon Fish. It’s about two little girls in China, one American and one Chinese, who become friends, run away from home to get away from their annoying brothers, and find work in a pawn shop until their fathers collect them in the evening. It’s quite sweet, and I bought it again for my daughter thirty years later.

I’ve always meant to read one of her novels for adults, but I never did.

Libraries used to shelve the works of Winston Churchill under the name “Winston S. Churchill”. So that he wouldn’t get confused with the famous one. Now, of course, virtually nobody even knows that the famous one ever existed…

(The other Churchill wrote the best-selling novels (in America) of 1901, 1904, 1906, 1908 and 1913, as well as the #2 book of 1915 and the #3 book of 1898.)

Somewhere I have a copy of a novel by Marie Corelli. Corelli wasn’t just the bestselling author in the world by far – her sales in her time (1880s-1920s) exceeded those of HG Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling combined. Now she’s known only through the insults sent her way from less successful (but in hindsight much more fondly remembered) authors.

I would say, though, that I’m not sure of ‘increasing quality’ as a good explanation – it may apply to SF&F, but the same phenomenon occurs in other genres, and it’s not just egregiously bad writers who are forgotten.

In fantasy, James Branch Cabell was not just the leading figure of the genre but a leading figure in American literature. He was spoken of as a candidate for the Nobel; his ‘Jurgen’ was described as the one immortal work of American letters. F Scott Fitzgerald and Mark Twain considered him their favourite writer. While his style (a sort of mixture of PG Wodehouse and T.S. White) is certainly old-fashioned, he’s an indubitably far better writer than at least 99% of fantasy authors in the half-century that followed (and still extremely readable – sometimes overblown, but at his best poetic, moving, and laugh-out-loud hilarious). And yet he’s almost entirely forgotten today. [except by some of his successors. I know Pratchett and Gaiman both cited him as key influences, and iirc Mary Gentle dedicated a novel to him]. Improving standards certainly can’t explain that.

Mostly, his decline is due I think to changing popular tastes. I came across a great comment (possibly by Hemmingway?) saying (to paraphrase) that after the Wall Street Crash, Cabell went around offering people visions of golden trinkets… while the people hungered for bread. Writers like Cabell – ironic, loquacious, suggestive, iconoclastic, ‘effeminate’, ‘Decadent’ – gave way to writers like Hemmingway (direct, understandable, reassuring, ‘muscular’). So Cabell fell out of fashion with the literary crowd, but was still too ‘literary’ for the pulp genre crowd.

But yes, although every forgotten writer has their own story, it’s true that only a fraction ever end up truly remembered – and often not the fraction you’d expect. Nor is it just literature. The most popular composer in Europe for several decades of the 19th century was John Field…

@102,

The Good Earth was required reading in my high school. I’ve not read anything of hers since.

@wastrel no. 104: Another example of historical events erasing fame: My local military history museum was given a lot of chaplain’s handbooks from WWII; they had so many they were selling them for $10, so I bought one for my hymnal collection. There are sections for Jewish (can’t speak as to which branch/es), Protestant, and Catholic services, and then a general songbook for the men in case they feel like making music, as one does. (Another thing gone down the memory hole…how many people these days assume that singing a song everybody knows is a good way to pass some downtime?) You’d presume that the editors of the manual would have picked the guaranteed sure-fire everybody-loves-it songs, right?

Stephen Foster. Including the minstrel songs, cringey fake dialect and ain’t-existing-while-black-funny-y’all and all.

@105, Never read that one. Imperial Woman and Pavilion of Women are my favorites, mostly for all the delicious details of Chinese homestead and Imperial Court life. World building again. I am a total sucker for world building.

@105 God that was a hideous pos. Sorry to any fans of it, but I’m in the camp that this was a pile foisted on us by the missionaries trying to make excuses for the warlords. If you read between the lines you can see why the communists won and, despite their evils since then, still maintain the “mandate of heaven”.

@wlewisii, 108: I read The Good Earth as being anti-modern, not Communist.

I read The Good Earth in grade school, and loved it, and I always thought it intended to show how bad the previous system had been. Went looking for the sequels, and they seemed to be thoroughly out of print.

The only reason I’ve heard of Cabell is that he’s mentioned in one of H Beam Piper’s books.

@110: Heinlein mentions Cabell explicitly a few times I think and alludes to his works a lot; Niven also has short stories that contain Cabell references

I found this list at http://www.hawes.com

1 BEYOND THIS PLACE, by A.J. Cronin. (Little, Brown.)

2 DESIREE, by Annemarie Selinko. (William Morrow.)

3 TOO LATE THE PHALAROPE, by Alan Paton. (Charles Scribner’s Sons.)

4 TIME AND TIME AGAIN, by James Hilton. (Little, Brown and Company.)

5 THE UNCONQUERED, by Ben Ames Williams. (Houghton Miflin.)

6 BATTLE CRY, by Leon Uris. (G.P. Putnam’s Sons.)

7 THE HIGH AND THE MIGHTY, by Ernest K. Gann. (William Sloane Associates.)

8 THE ADVENTURES OF AUGIE MARCH, by Saul Bellow. (Viking Press.)

9 THE FEMALE, by Paul Wellman. (Doubleday.)

10 THE DEVIL’S LAUGHTER, by Frank Yerby. (Dial Press.)

11 THE LADY OF ARLINGTON, by Harnett T. Kane. (Doubleday.)

12 COME, MY BELOVED, by Pearl S. Buck. (John Day Co.)

13 THE HEART OF THE FAMILY, by Elizabeth Goudge. (Coward-McCann.)

14 LOVE IS A BRIDGE, by Charles Bracelen Flood. (Houghton Mifflin.)

15 THE ROBE, by Lloyd C. Douglas. (Houghton Mifflin.) —

16 A SUNSET TOUCH, by Howard Spring. (Harper and Brothers.)

I’ve heard of seven and read six of these authors. Cry the Beloved Country was required reading in my high school only twenty (quite odd) years after its publication.

There is also, of course, a non-fiction best-seller list for that week. Unlike the fiction books, non-fiction tends to have a shorter useful life: a book about, say, sub-sea exploration, is quite likely to be useless except as a memoir, not as a source of information.

@111: yes, Heinlein was a massive fan. Several of his novels have subtitles homaging Cabell’s “A Comedy of _” format, and Heinlein’s “Comedy of Justice” (“Job”) looks to have structural parallels to Cabell’s version (“Jurgen”).

@108. wlewisiii

I feel if it were published today, it would be grimdark fantasy. It was just missing the evil magician.

1 OLIVER’S STORY, by Erich Segal.

2 TRINITY, by Leon Uris.

3 THE CRASH OF ’79, by Paul E. Erdman.

4 FALCONER, by John Cheever.

5 RAISE THE TITANIC!, by Clive Cussler.

6 HOW TO SAVE YOUR OWN LIFE, by Erica Jong.

7 THE CHANCELLOR MANUSCRIPT, by Robert Ludlum.

8 OCTOBER LIGHT, by John Gardner.

9 THE USERS, by Joyce Haber.

10 THE VALHALLA EXCHANGE, by Harry Patterson.

I’ve only read TRINITY. Interestingly, Alex Haley’s ROOTS was number one on the non-fiction list, but I’ve never heard of the rest on that list.

Speaking of old books, how many people here know where orual99’s name comes from? I’m betting a lot. Maybe even the majority.

@104 et cetera

I learned about James Branch Cabell through Fritz Leiber, In the introduction to one of his collections he mentions Jurgen as an influence on Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Decades ago I read all the Ballantine paperback “Adult Fantasy,” reissues of Cabell’s novels, and a few other titles that I managed to hunt down over the years, and for a while I did consider him my favorite fantasy author, perhaps my favorite author of any genre. Other commenters already mentioned Cabell’s influence on Gaimon, Pratchett and Heinlein; he was also admired by Ursula Le Guin (with some reservations: see “From Elfland To Poughkeepsie”) and Harlan Ellison (who used a quote from Cabell as an epigraph in Angry Candy.) David Gerrold mentioned Cabell in a recent story in F&SF; he’s probably also a fan.

However, Michael Swanwick, who appears to have read everything Cabell ever wrote, argues that most of Cabell’s work well deserves the obscurity that has since befallen it. Cabell’s writing, claims Swanwick, became increasingly self indulgent, pompous, dispirted and obtuse over the years; in short, that most of it’s dated very badly. He doesn’t find it surprising that Cabell, whose name was a household word in the early 20s, was already all but forgotten by the time he died in the 50s. (see “What Can Be Saved From the Wreckage? James Branch Cabell in the 21st Century”)

I’m afraid I found Swanwick’s critique quite persuasive.But I would still champion Jurgen and The Silver Stallion as minor masterpieces, and several other of his novels as flawed gems yet worth reading, particularly if you’re interested in exploring the pre-Tolkien roots of the fantasy genre.

While I agree that popular art is transitory, I disagree with this assessment:

90 per cent of the novels I come across today are poorly written, and from my experience with books from earlier decades, that was the case back then too. I don’t have to name the bestsellers of recent years that were passed on by multiple publishers due to the amateurish writing, only to find a mass audience that wasn’t bothered at all by creaky prose and shambolic plots.

Whatever benefits authors have gained form more widespread formal training in fiction in recent years has to be weighed against the fact we live in a less literate society than the mid-20th century. I’d wager the average 35 year old author today has spent much less time reading books (and much more on TV, streaming, twitter, videogames, etc.), and read less widely than her counterpart 50 years ago. Not to mention the sad fact that by their own admission publishers today put fewer resources into editing, mentoring, and gradually upping the game of new writers than they did in the halcyon days of publishing.

Changing tastes are down to evolving expectations around character, motivation, emotional proximity, authorial voice, pacing and the like – the current zeitgeist of the genre. I don’t think the quality of prose enters into it.

For F&SF, these won the awards in the year I was born. I’ve read all the Hugo winners but none of the Nebula winners. That probably means something.

NEBULA

Best Novel

Winner: Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes, published by Harcourt

Winner: Babel-17 by Samuel R. Delany, published by Ace

Best Novella

Winner: “The Last Castle” by Jack Vance, published by Galaxy Science Fiction

Best Novelette

Winner: “Call Him Lord” by Gordon R. Dickson, published by Analog

Best Short Story

Winner: “The Secret Place” by Richard McKenna

HUGO

Best Novel