Power is a most persistent taxman. As interesting as those examples are of the bodily tariff that attends tapping into extreme power (see Rock Lee’s Lotus taijutsu in his examination fight with Gaara in Naruto, the Elric brothers losing limbs in an attempted resurrection in Fullmetal Alchemist), I am much more fascinated by the intangible requisitions. Sure, you may be willing to sacrifice an arm or perhaps even your eyesight to wield the power necessary to defend/avenge your loved ones, but would you sacrifice your goodness? Would you sacrifice your sanity? In Robert Jordan’s masterwork series, The Wheel of Time, it is a question asked of every male channeler who wields saidin. Go ahead and tap into the One Power, energy powerful enough to manipulate the universe. We kindly ask that you leave your mental health at the door. That way lies madness.

(Note: That way also lies spoilers for the Wheel of Time series.)

***

Comm. Jamison: I must admit, his battle prowess is very impressive. He may be our answer.

Ringo: Yeah. Or our destruction.

(Teknoman, Episode 2: “Invasion”)

Sunday mornings in 1995-6 were a race against time. That was when UPN Kids aired an anime series known in the US as Teknoman. A heavily edited version of the Japanese anime Tekkaman Blade, it told the story of a war between Earth’s defenders, the Space Knights, on the one side and a race of giant arachnids called Venomoids and their overlords, the armored Tekkamen, on the other. At the story’s center is a mysterious young man named Slade who, with the help of a special crystal, can transform into his own Tekkaman and fight off the Venomoid invasion. It turns out that Slade is a sort of unfinished or incomplete version of the evil Tekkamen, his memories having been wiped when he crash-landed on Earth near the beginning of the series. It later comes out that being in Tekkaman form drains the host of its bio-energy, taxing the body and the mind. If Slade maintains his armored form for more than 30 minutes, he goes feral. It was the first time I’d seen this trope, a scenario repeated with Majin Vegeta in Dragonball Z and again when Uchiha Sasuke allows antagonist Orochimaru to possess his body in order to gain the power he believes he needs to avenge the death of his clan in Naruto. Not even Naruto is immune. Should he try to draw too much on the power of the Nine-Tailed Fox inside him and perform jutsus impossible for a shinobi of his age, he would eventually cede his entire will to Tailed Beast. When Jordan’s Rand al’Thor, the Dragon Reborn, Shadowkiller, He Who Comes With Dawn, first hears the voice of Lews Therin Telamon, the deceased leader of the forces of Light, in his head, that was as sure a sign as any that we had met our hero. Look for the man with the crown woven so tightly around his head, the thorns poke straight through the skull.

Saidin and saidar, the male and female halves of the One Power in The Wheel of Time, seem to hew, in their usage by characters, to stereotypes along the male-female binary, saidin use characterized by menace and brute force while proficiency in saidar is a reflection of a character’s dexterity and connection with others. Saidin is a rough torrent. One seizes it or wields it like a weapon. Its usage gives off a sense in those who perceive it of awe and menace. By contrast, one surrenders to the river of the One Power in order to use saidar. It is a thing to be embraced. Perhaps the most evident and consequential difference, however, lies in the Taint. Saidin has been afflicted by the Dark One and sets off a process of decay in the mind and body of the male channeler who accesses it. The physical rotting is twinned to a derangement that gobbles up greater and greater chunks of the mind. The channeler will hear voices, destroy the world around them, go feral. To prevent a second Breaking of the World, the Red Ajah of the Aes Sedai hunt down and “gentle” male channelers, severing their connection with the One Power. That a sort of castration is deemed necessary to save the world makes sense in a universe of gendered magic where hysteria wobbles precariously on a foundation of XY chromosomes.

The Latin word monere means “to warn.” Add a suffix and you have monstrum, a portent. A word winds its way through Old French, monstre, to give us what we know today as monster. Monster as Mayday signal (M’Aidez!). Monster as instruction. As injunction. Do not do as we do. Do not try to become us. That way lies madness.

The Taint on saidin presents monster as prophecy, a genetic predestinarianism bonded to what presents as an adamantine gender binary. But the taint is not all there is, and not all monsters are men. The Forsaken Semirhage knew how much pleasure she derived from using her healing powers and medical training to inflict pain. She did not need a covenant with the Dark One to tell her that.

***

“Hear me, X-Men! No longer am I the woman you knew! I am fire! And life incarnate! Now and forever—I am PHOENIX!”

(X-Men Vol. 1, Issue 101)

In October of 1976, the X-Men found themselves in space, as they are wont to do. At the tail end of a rescue mission, depicted in Uncanny X-Men #101, they lose control of their shuttle. Jean Grey, at the helm, attempts an emergency landing. Distraught at the thought of losing Cyclops, she wordlessly calls out for help. And thus begins one of the most heralded, controversial, and revered stories in American comics.

The being Jean beseeched during the shuttle’s descent was none other than the Phoenix Force, a sentient, formless energy, the immutable and immortal manifestation of life. When the Force becomes flesh and succumbs to the influences of others, it turns Jean into the most destructive being in the universe. As Phoenix, she consumed a star, setting off a supernova that obliterated a nearby planet, incinerating its five billion inhabitants.

During the final battle in issue #137, between the X-Men and Jean’s captors, the Shi’ar, the Dark Phoenix reemerges. Struggling to remain in control of the most powerful force in the universe, Jean begs Cyclops to end her life. Frightened at what she has become, she confesses that a part of her liked having the power of the Phoenix. A part of her, Jean, thrilled to it. In the end, Scott can’t bring himself to do the deed, so Jean sets an ancient Kree weapon on herself, ashes to ashes.

Much has been and remains to be written about societal pathologies toward female power (Dark Phoenix couture: big BDSM energy), of sex and lust and control, of logic and desire and the desire for logic and the logic of desire, of responsibility and irresponsibility, of mastery of magic and gender, of who gets to be god, consequences be damned. But I am far from the most qualified scribbler to put that book together.

It is all to say that sometimes when I think of Jean Grey’s prayer into the void and that answer that took the form of the Phoenix Force, I think of Mierin Eronaile, an Aes Sedai researcher during the utopian Age of Legends dissatisfied with the gender split in the use of saidin and saidar, who felt the division was an impediment to scientific progress, and who, during her research, stumbled upon a source of power outside of the Pattern, an energy source that could be touched by male and female hands alike. Mierin Eronaile, who loved the social cache of being Lews Therin’s lover without loving Lews Therin himself but who lived in an age when immorality bore no rewards. Mierin Eronaile, one of the most powerful female channelers of her time, driven by the marriage between ambition and scientific inquiry. Who, in thrall to the charm of discovery, ended up boring a hole straight to that unknown energy source, allowing the Dark One to leak into the world and bring about the Collapse. Mierin Eronaile, who would submit herself to the Shadow, become one of the first Aes Sedai to betray humanity, and bestow upon herself a new name: Lanfear, Daughter of the Night. She haunts the dreams of Rand and Perrin, urging them to take glory for themselves. “Dreams were always mine, to use and walk. Now I am free again, and I will use what is mine,” she says to Ba’alzamon in Chapter 36 of The Dragon Reborn, the chapter titled after her. And that is how she hunts. Though the Age of Legends is cast in the nomenclature of utopia, humans were not without their worst selves. Perhaps the Dark One’s greatest power move against the forces of Light was to give people permission to be. Lanfear chases power through a paramour. The difference between that and what Mierin did is simply a matter of scale.

I think of Jean Grey wanting to save the lives of her friends and being granted the power of a god. And then I think of Lanfear wanting to recapture the affections of the lover who spurned her and being granted one of the most prestigious posts among the Forsaken in the War of Power. She spends the rest of that life hunting Rand al’Thor, sensing him to be her once-lover reborn, seducing him with her beauty, with the promise of power and glory, visiting him in his dreams. But power breeds addicts. Jean tasted it. Lanfear had as well. The Shadow offered access to an energy source that operated beyond the restrictions of sex, a promise that there existed a roaring ecstasy too angry and powerful for the prison of a gender binary. The Forsaken became the Forsaken for diverse reasons—avarice, nihilism, jealousy—and they warred amongst each other and schemed and plotted in order to become the one whom the Dark One would choose as Nae’blis and allow to touch the True Power. How that must have looked to Mierin.

In both the Phoenix Force and in the Dark One’s promise of the True Power lies the promise of ego-death, a beyond. I can’t believe that electric currents ran through both Jean and Lanfear merely at the prospect of obliterating planets and coercing ex-boyfriends into taking them back. When Jean confesses to Cyclops that a part of her enjoyed being the Phoenix, one imagines nestled somewhere in the pit of Scott’s stomach past the horror, the question “why”.

Ask Lanfear why she chose what she chose, why she adopted monsterhood, and I don’t know that getting Lews Therin back would be her answer. I’d like to think she would spread her arms to indicate the world around her and say, quite simply, “because.”

***

“I thought I could build. I was wrong. We are not builders, not you, or I, or the other one. We are destroyers. Destroyers.”

(Lews Therin Telamon to Rand, Winter’s Heart, prologue)

The trope demands that, should the character’s arc not end in death, there must at least be a maiming. Teknoman Slade defeats Darkon but at the cost of his memory and his ability to walk. Sasuke, newly empowered, finds the brother who murdered their clan and kills him only to discover that this brother had spared Sasuke not out of contempt but out of love. Uchiha Itachi’s final act is to pull from Sasuke the curse that had tainted him, the evil Orochimaru, and to seal the villain in his sword. The mission that had defined Sasuke’s life is revealed to have been a manipulation and dying in front of him is the man who had perhaps loved him the most in the world. Jean Grey and Majin Vegeta both choose self-immolation, sacrificing themselves to save their beloveds.

Rand, however, in concert with Nynaeve, cleanses the Taint. Using access keys to the most powerful male and female sa’angreal, the Choedan Kal, Nynaeve links with Rand. But when she recoils in horror at the chaos and rage of saidin, Rand takes control of the link, at first trying to bully saidar the same way he wields saidin and only later understanding that saidar must be guided, that it was something one must surrender to. Creating a conduit with saidar, Rand funnels Tainted saidin through it straight into the maw of Mashadar, the malevolent, unthinking entity coating the city of Shadar Logoth in evil. The Taint and Mashadar annihilate each other, leaving a massive crater where the city once stood. Both Rand and Nynaeve survive, and the impossible has been accomplished, even though the female Choedan Kal was destroyed in the process. That is the note on which Winter’s Heart, Book 9 in the series, ends.

It isn’t until Knife of Dreams, Book 11, that we discover that the Amayar, an island people who lived near what had been Shadar Logoth saw what happened, saw the breaking of the female Choedan Kal on their island of Tremalking, and, believing this sign to have heralded the end of days, committed mass suicide by poison.

A people had been sacrificed so that male channelers might wield saidin absent the threat of madness. But who could do what Rand did, learn of this consequence, and not feel as though they had been asked the questions posed at the outset of this essay? Would you sacrifice your goodness? Would you sacrifice your sanity?

What if the Taint, singularly afflicting male channelers, is simply a refracted prism of the notion that not only does power corrupt indiscriminately, it taxes without quarter?

If men are the easy mark, they aren’t the only. “Don’t worry. It won’t happen to you.” No matter what that voice sounds like, it is always the Devil’s.

***

“What makes you think you can keep anyone safe?”

(Lews Therin to Rand in Crossroads of Twilight, Ch. 24)

Cleansing the Taint doesn’t inoculate male channelers from committing horrors any more than kicking an addiction to drugs and alcohol cures a person of their existing defects of character. Before the series’ end, Rand will have tortured his lover, Min Farshaw (albeit under mind control). He will have nearly murdered his father (no mind control). He will have destroyed an entire building using the Choedan Kal, wiping the entire palace out of time, in pursuit of one of the Forsaken (no mind control here either).

During the final battle, Rand and the Dark One show each other competing futures, what would happen were either to win and destroy the other. After dueling visions, Rand presents a reality where there is no Shadow, no Dark One. But therein lies the nightmare. In Rand’s world, people would have no choice but to do good. In what way does that differ, the Dark One posits, from a world in which people are uniformly compelled toward evil?

Therein lies the key to my appreciation of the Deal with the Devil trope in the Wheel of Time and elsewhere. It implicates choice. At every stage, it implicates choice. In that respect, the Taint is scaffolding. Does the Taint on saidin make men more uniquely dangerous? Yes. Are men still uniquely dangerous without it? Yes. A capacity for hurt is not a chromosomal certainty. A penchant for bedlam does not discriminate. What happened to Jean Grey is not an outgrowth of a unique perversion but rather a unique outgrowth of a universally personal perversion.

The monster tells you what it is, issues the warning, saying “if I give you this, you will become it,” and you take its hand and think no, I will do differently. What could convince someone so completely of that assertion, that they will escape consequence, other than madness?

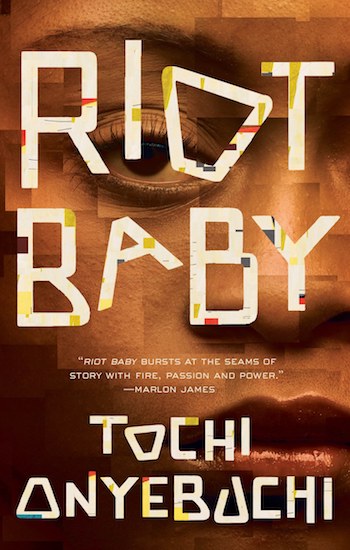

Tochi Onyebuchi’s fiction has appeared in Panverse Three, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Obsidian, and Omenana Magazine. His non-fiction has appeared in Nowhere Magazine, the Oxford University Press blog, and the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy, among other places. He holds a B.A. from Yale University, a M.F.A. from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, a J.D. from Columbia Law School, and a Masters degree in droit économique from L’institut d’études politiques. His debut young adult novel, Beasts Made of Night, was published by Razorbill in October 2017, and its sequel, Crown of Thunder, was published in October 2018. His next YA book, War Girls, will hit shelves on October 15, 2019, and a novella, Riot Baby, will be available from Tor.com Publishing in January, 2020.

Tochi Onyebuchi’s fiction has appeared in Panverse Three, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Obsidian, and Omenana Magazine. His non-fiction has appeared in Nowhere Magazine, the Oxford University Press blog, and the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy, among other places. He holds a B.A. from Yale University, a M.F.A. from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, a J.D. from Columbia Law School, and a Masters degree in droit économique from L’institut d’études politiques. His debut young adult novel, Beasts Made of Night, was published by Razorbill in October 2017, and its sequel, Crown of Thunder, was published in October 2018. His next YA book, War Girls, will hit shelves on October 15, 2019, and a novella, Riot Baby, will be available from Tor.com Publishing in January, 2020.