The very idea of recommending summer reading to steampunks seems a bit odd. It conjures images of those cumbersome full body swimsuits of bygone years; while such swimwear might drag one straight to the bottom, it also eliminates the need to apply sunscreen.

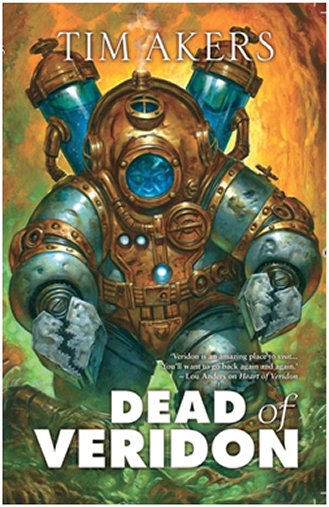

Nevertheless, I suppose if one was thinking of steampunk reading for the beach, in bikini or bloomers, they could do far worse than Tim Akers’ Dead of Veridon.

Summer reading, by my own definition, should be light reading. The beach is not the place for Proust. (I’m dubious as to there being any place for Proust, but that’s another discussion.) The beach is where I read Clive Cussler, Stephen King, and stacks of Conan, and Doc Savage paperbacks. So when I recommend Dead of Veridon, I hope you’ll understand that I’m not endorsing it as the best bit of steampunk fantasy I’ve ever read, or even read this year. That said, I found it an engaging, page-turning read, despite some shortcomings that only bother pretentious academics.

One of Dead of Veridon‘s greatest strengths is that, despite being a sequel, it reads very well as a standalone novel. While aware of Heart of Veridon, the first book in The Burn Cycle series, I never got around to picking it up. Having forgotten about it entirely when I started Dead of Veridon, I dove into the novel without any questions in my mind as to whether or not I’d understand the context. Thankfully, Akers does an admirable job of updating new readers, without excessive exposition. Flashbacks to the events in Heart of Veridon were character-based, flowing naturally into the narrative. It was only when the name “Veridon” had twigged at my mind enough times that I did a search, and remembered the first novel.

The Burn Cycle, like Akers other steampunk-fantasy, The Horns of Ruin, is a mixed bag of really excellent worldbuilding with odd character voices. While it’s more apparent in Horns of Ruin, Aker has a propensity toward hard-boiled characters: noir badasses with a heart of gold. While the idea holds promise, neither of my experiences with Akers’ writing has endeared me to his characters. Both the foul-mouthed, Gen-X ‘tude of the ostensible paladin of Horns of Ruin nor the disinherited, exiled nobleman turned street-wise thief of Jacob Burn in Dead of Veridon lack a core consistency I can’t chalk up to complex characterization. Jacob Burn switches from dead serious chip-on-his-shoulder to cavalier, devil-may-care jokester without warning: Aker is at his best with his protagonists when they’re taciturn or bitter: he’s better at gravitas, while his levity leaves much to be desired.

Thankfully, these ham-handed attempts at comic relief are fewer than the moments of violence or tension. The first 60 pages drew me in effortlessly, chronicling a descent into a dark river filled with living dead, a delivery of a mysterious object, and the ensuing and unexpected assault on the city of Veridon by the river’s undead. These aren’t your usual stripe of zombie: Akers’ superior world-building extends to these river-born revenants:

“And that was the trick, the thing that made the Fehn so unsettling. They were our dead. Anyone who died in the river, drowned or dumped from some harbor back alley, any body that slipped beneath the Reine’s dark waters became their property. Their citizenry. The Fehn were a symbiotic race, their mother-form hidden away in the depths of the river, but they infected the bodies of the drowned.” (23)

When the Fehn turn violent and flood into Veridon, Jacob Burn is given a mystery to solve. While it is connecting to his past, the reveals worth reading for in Dead of Veridon are less about character development than political intrigue and thaumaturgic technology. While I’m not fond of Akers’ character voices, the spaces those characters inhabit are of thorough construction. The excellent divine spellcasting in The Horns of Ruin and the Fehn’s nature in Dead of Veridon were equally captivating.

Readers looking for character-based steampunk should seek elsewhere (arguably Gail Carriger or Mark Hodder). Those who enjoy their steampunk tech with a high dose of technofantasy, their “punk” to be the criminal element in a corrupt society, and pulpy dialogue should pick up Dead of Veridon. Though if you’re reading it at a beach, you may find yourself eyeing the water warily from time to time.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.