“…What the Wolf Brothers do you won’t survive. Although you might be of more use to them alive and unharmed. Which means you must definitely kill yourself.”

“Self-murder is a sin.”

“Letting yourself be captured is a worse one.”

“To God?”

“To Venice. Which is what matters.”

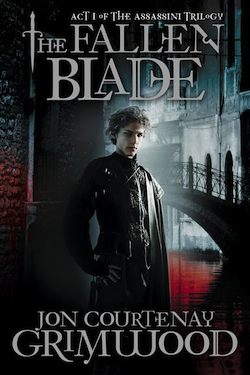

—Jon Courtenay Grimwood, The Fallen Blade (2011)

To date, Grimwood’s been better known for science fiction than for fantasy. Since 2000’s redRobe, he’s been nominated for the British Science Fiction Award every year he’s been eligible, winning in 2003 and 2006, and he’s been twice nominated for the Arthur C. Clarke Award. You can’t call that anything but a record of success.

2011’s The Fallen Blade is his first novel since 2006. It marks a new departure, one which passes over the hard-edged alternate futures of cyberpunk universes in favour of a razor-edged and darkly fantastic alternate past. And this is one alternate past which reminds me rather strongly of Mary Gentle’s Ash in its depth and complexity, although its style and focus is rather different.

The year is 1407. In the east, Timur rules a conquered China; while in the Mediterranean Mamlukes and Byzantines squabble with Venetians and Genoese to control the seas. In Venice, the descendents of Marco Polo rule the city, Millioni who have reigned from the ducal palace for five generations. The present Duke Marco is a simpleton. His mother the Duchess Alexa vies with his uncle Alonzo, the late Duke’s brother, for power—and to preserve Venice—in his name, while Atilo il Mauros, chief of Venice’s feared assassins, leads a losing battle against the krieghund of the German emperor among the canals and streets of the city.

Lady Giulietta, the duke’s adolescent cousin, is a pawn in the hands of the powers striving to hold sway over Venice. So is Tycho, a boy with strange abilities and stranger hungers, who combines shocking vulnerability with flashes of monstrous savagery. The two are linked in a way which neither completely understands, and which drives Tycho without his comprehension even after his capture by the Duchess Alexa and her pet strega, the girl A’riel, and his training as an assassin at the hands of Atilo the Moor. In the end, in the face of a Mamluke war fleet, it will drive him to embrace the most monstrous aspects of himself to survive.

Grimwood has a minimalist, lucid prose style, and a deft turn with imagery which he uses to good effect. The characters are well drawn and, even in their worst acts, depicted with understanding and empathy, but this isn’t a book for the squeamish. It’s dark and shot through with brutality and savagery, the murder of children and the death of innocents. Dark in more ways than one: if The Fallen Blade were a film, it would probably be lit in a kind of tenebric chiaroscuro, for most of the action takes place at night, and when it does take place in the light of day the tone remains shadowed and grim, even stark.

While The Fallen Blade lacks the hectic stylised narrative fragmentation of Grimwood’s Arabesk trilogy, this is still a book that demands you pay attention. Events and personalities are elucidated as much by implication as by exposition, and Grimwood displays no hesitation in shifting between times and characters with little or no explanation of the Meanwhile, back on the farm variety.

But if you do pay attention, The Fallen Blade is a rewarding read which gathers pace and tension to a suitably nerve-wracking conclusion—savage battle, the revelation of dangerous secrets, and the promise of more to come.

Liz Bourke is reading for a postgraduate degree in Classics at Trinity College Dublin. She also reviews for Ideomancer.com.