2020 is a difficult year for reading novels about the American Civil War. The old comfortable myths, the familiar interpretations of history, have developed serious fractures. The romance of the Confederacy has given way to the dismantling of Confederate war memorials. The election of an African-American President represented both the power of cultural change and the vehement, even violent opposition to it.

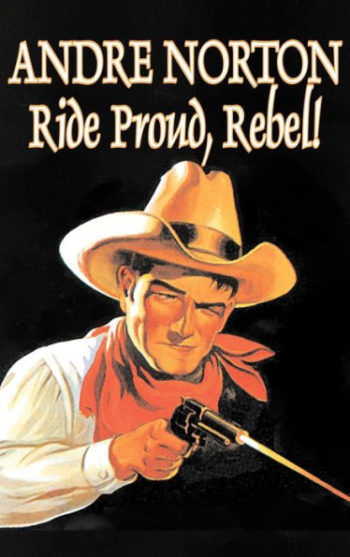

Andre Norton published Ride Proud, Rebel! in 1961, in the midst of the Civil Rights era. Her science fiction novels took care to depict a future that was not all or even mostly white, and she tried hard to write Black and Native American characters with respect and understanding. And yet she chose this material for a foray into historical fiction.

She imprinted in youth on Gone With the Wind, which is evident in her first novel (though published second), Ralestone Luck. But a generation had passed and her work had moved on to very different genres and philosophies. In fact, I wonder if this is another early trunk novel, written before she did serious thinking about race and culture in the United States.

Whatever motivated it, here it is. Fiery young Kentuckian Drew Rennie has defied his wealthy, Union-sympathizing family and joined the Army of the Confederacy. We meet him late in the war, still in his teens but already a hardened veteran. Despite the determined optimism of his fellow soldiers, the end is already in sight.

Buy the Book

Trouble the Saints

Drew’s rebellion is personal. His parents, he’s been raised to believe, are both dead. His father was a Texan, his mother a daughter of the house. When she became pregnant and her husband was apparently killed in war against Mexico, her father stormed down to Texas and hauled her back home. There she died after delivering her son.

Drew has a lifelong hate-hate relationship with his grandfather. He gets along, more or less, with the rest of the family, though all of them are on the other side and one is married to a Union officer. As the story progresses, he becomes the very unwilling protector of his young cousin Boyd, who wants to be a rebel just like Drew. Boyd runs away to join the Confederates; much of the action, in and around historical battles and skirmishes, consists of Drew trying to track down his wayward cousin and force him to go home.

That much of the plot is very 1961. Teen rebellion was a huge industry. The short life and tragic death of James Dean was its epitome, and his most famous film, Rebel Without a Cause, encapsulated the mood of the time.

Maybe that’s why she chose to write about the Civil War. It offers a dramatic backdrop for teen rebellion, with careful historical research and a battle-by-battle depiction of the final throes of the Confederacy in Kentucky and Tennessee. There’s a family secret and a mystery to solve, and there’s a direct lead-in to a sequel, in which Drew Goes West, Young Man to find out the truth about his father.

Drew is kind of a cipher, despite his personal conflicts, but some of the other characters are as lively as Norton characters get, including Boyd (though he’s also quite annoying) and the dialect-drawlin’ Texan, Anse Kirby. A Native American scout plays a strong role, and now and then a female character gets a decent number of lines.

Much of the action devolves into summary and synopsis of numbingly similar battle scenes. As often as characters get shot in the arm or shoulder, I feel as if I’m watching a Hollywood historical epic. Gallop gallop gallop pow! pow! off flies the soldier, winged in mid-flight. Drew gets knocked out and misses key battles, which have to be summarized after the fact. And in true series-regular fashion, he never suffers any serious damage, though the same can’t be said of the humans or equines around him.

The equines are amazingly well and accurately drawn. I wouldn’t have expected it of Norton, based on the way she generally portrays them, but this is a surprisingly horse-centric book. Drew’s family breeds horses, and he loves and understands them. He’s in the cavalry; when we meet him, he’s trying to round up horses for the army, and he’s riding a true horseman’s mount, a tough, not at all physically attractive, smart and savvy gelding named Shawnee. Shawnee, without a speaking part, still manages to be one of the novel’s more memorable characters, as, later on, does the mighty Spanish mule, Hannibal. Even the rank stud is well portrayed, and we get to see what Drew has to do in order to manage him on the trail and in camp.

Drew really is a convincing horse (and mule) man. He doesn’t fall for flash and pretty, he understands the true blessing of a smooth-gaited mount for spending long hours in the saddle, and we see exactly what those hours do to both the rider and the mount. When I was driven to skim the battle scenes—they are sincerely not my cuppa—I slowed down to enjoy the equine portions. She got them right.

And yet the novel, to me, felt hollow at the core. We are never told what the Cause is that Drew is fighting for. As far as anything in the story indicates, it’s a nebulous conflict, brother versus brother, fighting over land and resources. Drew is on the Confederate side because his grandfather is Union. What those two things really mean, we’re never actually told.

Drew’s world is overwhelmingly white, with a couple of token Native Americans (and some reflexive racism in that direction from the Texan, going on about the cruel, savage Comanche whose torture techniques come in handy for terrorizing bandits and Union soldiers). Once in a great while, we see a Black person. There’s a Mammy figure back home on the plantation, there’s a servant or two. Near the end we see an actual Black regiment fighting for the Union. We’re never told what that means. Or what the war is about. The words slave and slavery just… aren’t a factor.

It’s a massive erasure, and it’s compounded by the heroic portrayal of Nathan Bedford Forrest, under whom Drew eventually (and wholeheartedly) serves. Forrest here is heavily sanitized, turned into a hero-general. We hear nothing about his history, his slave trading and his atrocious treatment of his human merchandise. There’s no hint that his Cause might just happen to be unjust. Even while Drew tries to disabuse Boyd of the notion that war is all jingling spurs and flashing sabers, the war he fights is just as steeped in myth and denial, though it’s notably grittier.

I want to know how the story ends, despite the problems with the first half, so I’ll be reading Rebel Spurs next. As it happens, the first chapter takes place right down the road from where I sit, in a town I know quite well. That should be interesting.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café and Canelo Press. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.

Certainly my first thought was “trunk novel”!

Reminds me of Manly Wade Wellman’s Rebel Mail Runner. (Also the very bad, but delicious novels of J.T, Edson) Southerners were fighting for ‘states rights’ and to ‘keep their sacred way of life.’ Slavery- what’s that?

There was a lot of Denial even at the time that the Cause was in fact slavery but it was.

The Comanche are my absolute favorite Native American nation and while torture of captives certainly happened it was an individual choice not a cultural norm or established institution. The Comanche were quite libertarian in their attitudes. They had customs and traditions but nothing was carved in stone. As one Anthropologist put it; ask a Comanche any question about practices and rules and the answer will start with ‘It depends -‘

I’ve never read any Norton but yep she’s glossing over everything. For contemporary sources, see Luther E. Warren’s Yellar Rag Boys, which was about the Arkansas Peace Society who were pro-Union and pro-abolition. Some of the members joined the Union army; there were units organized in Arkansas.

I don’t think the legal, social, and philosophical issues involved with the Civil War were significant to – or even comprehended by – most of the people fighting in it.

We would do well not to insist that our books share our opinions.

@3 I’ll be interested in your comments on the next article. I haven’t read the book yet, just skimmed the opening, so we’ll see what we’ll see.

@5 The point of a reread series is exactly that: to reread an older work in the light of one’s contemporary life and views, and to state one’s opinion accordingly.

“The romance of the Confederacy has given way to the dismantling of Confederate war memorials.”

The Confederacy can only be romantic if you know very little about it. I like Norton, but will give this one a wide miss.

@5

Both sides were very clear about their ideology and aims, as were their leaders. See any of Lincoln’s speeches, the “cornerstone” speech of CSA VP, the state secession documents, contemporary letters and newspapers. Two good recent books on this topic are What a This Cruel War Was Over, and For Cause and Comrades.

Msb, My experience of first hand sources, such as Mary Chesnut’s Diary, is that participants are studiously vague about the exact nature of the sacred Cause. Mary for example claims to be very anti-Slavery while totally pro ‘Cause’. It’s kind of weird actually. There are some who openly champion slavery but many seem to avoid the subject as best they can.

Princess, glad to find another Mary Chesnut fan. Chesnut is really clear about her own oppression by Southern (White) patriarchs but refuses to look at the role of race, because slavery is necessary to preserve her status as a white “lady”. This is a willful silence. How otherwise can she “hate” slavery but fully support a government explicitly dedicated to its preservation and expansion?

Many, many other Confederate female diarists are much clearer in their analysis of what was at stake. See Stephanie McCurry’s Confederate Reckoning, Drew Faust’s work, an older book, George Rable’s Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism, or even the women (and men) quoted in Burce Levine’s Confederate Emancipation.

I’ve never entirely bought Mary’s ‘oppression’. Yes she is annoyingly dependent on husband and father in law but she doesn’t let it cramp her style. Comparing her condition to that of a slave, as she does, is downright offensive considering what black slave women were up against. But almost no other first hand source write as well as Mary does. Do you have Woodward’s Mary Chesnut’s Civil War?

I’ve never entirely bought Mary’s ‘oppression’. Yes she is annoyingly dependent on husband and father in law but she doesn’t let it cramp her style. Comparing her condition to that of a slave, as she does, is downright offensive considering what black slave women were up against. But almost no other first hand source write as well as Mary does. Do you have Woodward’s Mary Chesnut’s Civil War?

@7: Indeed, and the aim of the Union was to maintain the union of states. As Lincoln quite openly stated, if he could have preserved the Union while maintaining slavery, he would have done so.

Indeed. Though he added that he believed all people should be free he saw his job as president to be to save the Union above all. Happily that meant in the end eliminating slavery.

This may be of interest for those who hold to the doctrine of “It was of its time:”

https://twitter.com/MermaidSailor/status/1231217577982091266

“Do you have Woodward’s Mary Chesnut’s Civil War?”

Yes, indeed.

@@@@@ 14

wow, thanks! GWTW is very impressive as a look at the various social roles open to white women (mostly “ladies”) in the old South, and as an argument for educating women (to avoid the fate of psycho Scarlett), but the Racism Fairy has destroyed both book and movie for me.

and this “of its time” argument is so feeble. Harriet Beecher Stowe, the Grimke sisters, Sojourner Truth, Sumner, Douglass, etc. etc. etc. were just as much of their time as slavery apologists.

@16 Isn’t it fascinating? And disturbing when you realize how much still hasn’t changed, and how many serious efforts there are to roll back what changes have been made.

@17: > And disturbing when you realize how much still hasn’t changed,

What’s disturbing is how little understanding of history so many people have.

@18

Indeed. For example, it’s pretty depressing to have a guy at the hearing on removing the bust of slave trader, orchestrator of the Fort Pillow massacre and KKK founder Nathan Bedford Forrest actually argue that the bust should be retained because Forrest was less a massacre-er than a butcher. As one of the legislators asked, how many people can you butcher and still be honored by the state of Tennessee?

@16, Personally I’ve never managed to get all the way through either book or movie. Which is unusual for me. Usually I can suspend judgement as well as disbelief but not in the case of GWTW.

A major part of the reason I ardently dislike Mr Bernard Cornwell’s STARBUCK CHRONICLES – the only one of his series I actively dislike, though my attitude towards the protagonist of his SAXON SAGA is Love/Hate at best and I’m still terribly, terribly disappointed in REDCOAT for obliging young Sam Gilpin to turn traitor* – is because it takes much the same “eh, it’s all relative” approach to The Southern Cause.

While it seems a pretty fair reflection of an Angry Young Man’s indifference to what he’s doing to tick off his Old Man so long as Dad/Grandad/Wicked Stepfather ends up seething, it does NOT make for an especially admirable protagonist.

*Did I mention that I am so very, Very British?

@12.melendwyr: It bears repeating that THE hot-button issue that had put the Union of States in peril in the first place was the fact that The South (or at least the Southern decision makers) were increasingly convinced that if they stuck with the United States of America their cosy, slave-owning superiority would wither on the vine because the North was steaming into the future while Dixie was paddling to keep its head above the water (with the demographic consequences one might image, including a steady increase in the number of Representatives they could send into Congress).

@21: I’ve heard people argue that the hidden factor that precipitated the Civil War was that the South was sending people into the western territories to tip the vote on whether to be incorporated as slave or free states. (That sort of thing was a lot easier before modern communications and ID systems existed.) Northern leaders found this both ethically distressing and economically disadvantageous, thus the increased political pressure on the southern states that finally pushed someone to do something stupid and provide a casus belli.

Regardless, the actual day-to-day experience and the reasons for fighting of the vast majority of soldiers on either side would have had little to do with either the ethics of slavery or political machinations.

“Regardless, the actual day-to-day experience and the reasons for fighting of the vast majority of soldiers on either side would have had little to do with either the ethics of slavery or political machinations.”

This is not true. A lot of primary materials (comment 7) disagree with this statement. The Confederates were very clear about aiming to create and build a slave-holding empire, to the extent of kidnapping black people for later sale while invading a Pennsylvania. And McPherson’s For Cause and Comrades shows the same was true for Union soldiers, who actively recruited freed slaves when invading the South. Of course personal factors varied, but both sides knew quite well what they were risking, and in many cases losing, their lives for.

Since it’s clear that we’re not going to come to a definitive agreement on the factors, motivations, and history in question here, let’s move on to other book-related topics, or leave things there. The article discussing the sequel will be up on Monday afternoon.

@25

fine with me. Your house, your rules. Looking forward to the next post.

@25.Moderator: Message received and understood, thank you very kindly. (-: