SFF is not kind to Asians, and I learned that when I watched Blade Runner for the first time a few years ago. I had heard it as pivotal for the science fiction genre.

Blade Runner was released in 1982, at the height of the Japanese economic boom, where there were whispers of Japan surpassing America’s gross domestic product. The futuristic world of Blade Runner, with neon Chinese characters on the walls and a perpetual giant geisha surveilling the characters, the blatant Japonisme represents an anxiety towards loss of racial country, a kind of worry that Japan and the rest of east Asia will take over the world through sheer economic force. There are no Asian characters in Blade Runner, at least no characters with any agency, if you want to argue about the eye maker. The movie is about class exploitation and gendered labor, butcher fantasies about the future is limited by their othering of Asians and Asian culture. The “futuristic” world building of Blade Runner represented current anxieties about Asian economies, but also demonstrated the limited imaginations directors and writers had about racial harmony and diversity.

This made me skeptical about SFF’s view of Asian culture. Asia, from what I understood about SFF from Blade Runner, was fertile land for white western imaginations; A pretty background to make the future seem exotic and foreign and fresh, but not enough to genuinely include Asians as citizens with agency and power.

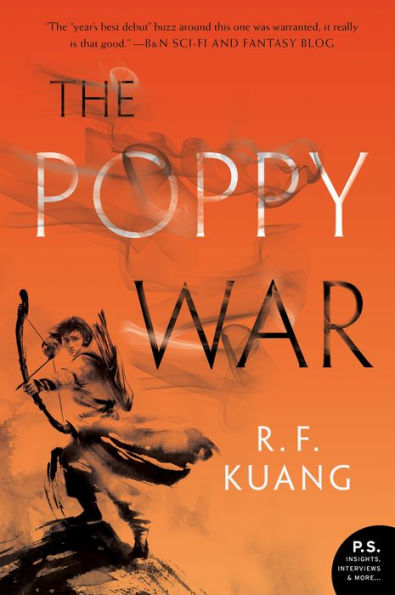

It wasn’t until I read R. F. Kuang’s The Poppy War that I felt accepted in an SFF Asian setting, presented by authors of Asian descent. Kuang’s worldbuilding mattered to me, and struck me. She showed me what genuine Asian SFF worldbuilding looked like— work that drew inspiration from Asian culture, had truths that people without background could learn from and made Asian Americans smile like they’ve finally been in on a joke. During one of Rin’s strategy classes, the students have to solve a problem where the army has run out of arrows. One of Rin friends, Kite, suggests filling boats with straw dummies and ambushing the opposing army on a foggy night. The enemy soldiers would shoot arrows at the dummies, thereby replenishing arrows for their army. The strategy is lifted from Zhu Geliang’s Borrowing the Enemy’s Arrows strategy from Romance of the Three Kingdoms, one of the four most important works of Chinese literature.

I felt seen by the references that R.F. Kuang nods to, from childhood cartoons like Nezha and references to Chinese literature like the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, to more horrifying wartime tragedies like the Nanjing Massacre and the Unit 731 experiments. Finding the references in The Poppy War was a stark contrast from the time my 10th grade English class, which was mostly composed of Asian immigrant children, received Cs from our teacher for missing the “extremely obvious biblical symbolism” in a book. All of those silly folk stories that had been gifted to me by my parents when I was younger, that I thought no one found any value in because no teacher or professor of mine had talked about them, were represented in The Poppy War. Her book set me on a path to read and support Asian American authors who used their own histories and folk stories as inspiration for their work, and to think more about the radical potential of inclusive world-building.

Thus, here are my recommendations for five stories by Asian SFF writers who write about Asia. Perhaps reading them will help us rethink “Asian steampunk genres” or “techno orientalism” and learn more about Asia and Asian history as a whole. I’ve tried to point out actual cultural references and historical references in each book to give a starting point, and I know that I am now more curious about Southeast Asian history and South Asian history because of these books.

Ghost Bride By Yangze Choo

The southeast Asian world of Choo is colorful, fanatical, and true to Chinese folk customs and history. This book is set in Malaysia, and is about a woman who is offered to be wed to a recently deceased man. The ghost man visits her in her sleep and she is pulled into the Chinese spirit world to solve a murder mystery that involves both their families and their pasts. While not at the forefront of the novel, Choo introduces the reader to the complicated group dynamics of colonial Malaysia, called British Malaya in the novel, and ruminates on the different groups of people that live in Malaysia, including the ethnic Chinese, the Muslim Malaysians, and the westerners. The main characters are Chinese Malaysians, and the setting is largely focused on Chinese funeral rites and beliefs. The main character burns joss paper, known as spirit money, a Chinese tradition which allows for the spirit to live comfortably in the afterlife. There are mentions of historical violence as well, including the Manchurian takeover of China during the Qing dynasty, in which the Manchurians outlawed Han Chinese dressing styles and made all men style their hair into the infamous queue braid. The book has also spawned a Netflix adaptation, which can be viewed in the United States.

The Devourers by Indra Das

This book, which is cross published in the United States and India, is about werewolves in different periods of Indian history. The Devourers starts in modern day Kolkata, India, where a professor named Alok Mukherjee speaks to a stranger about the existence of werewolves: humans who can take animal skins. The middle part of the story is set in Mughal India, and we take on the perspective of Alok as he searches for stories of werewolves in the archives. The protagonists, while they journey, are privy to the building and rebuilding of the Mughal empire, witnessing the grand Fatehpur Sikri become abandoned. The final parts of the book are in the forests of the Sundarbans near the Bay of Bengal, where the main character of that part of the story meets with traders from the British East India company, and explores the legacies of British colonialism of India. In fact, the entire story is a metaphor for the impact of British colonialism, as “werewolves” and “lycanthropy” are European terms, their myths brought by traders and colonists. The main werewolf is the product of his European werewolf father raping his Muslim sex worker mother, forbidden by werewolf custom. In India, shapeshifters can take on different forms of animal skin, and shapeshifters from the Sundarbans are more tigerlike. The story is a beautiful examination of what it means to be human, while also examining colonialism, love, and cannibalism. Content warning for graphic depictions of rape, sex, and violence.

Hunted by the Sky by Tanaz Bhathena

Bhathena writes a historical fantasy about a girl named Gul with a star shaped birthmark, whose parents are murdered by King Lohar’s Sky Warriors, whom she then vows revenge on. She meets a group of women called The Sisterhood of the Golden Lotus, which is inspired by Indian and Persian folklore of female warriors, and plots her revenge on King Lohar. The setting is in the Kingdom of Ambar, which is roughly inspired by the Vidal Courts of medieval India and the Rajput Kingdoms. Unlike the unified Empire of Mughal, the Rajput Kingdoms were disparate and were constantly fighting. There are four kingdoms in this “World of Dreams” Universe: Ambar, Prithvi, Jwala, and Samudra, which correspond to the four elements of air, water and fire respectively. And while Bhathena does explore the unequal class status of magical and nonmagical people, there is also an acceptance of diverse sexualities and a queer supporting character in Ambar. I found this book difficult to get into at first because of the frequent usage of Hindi words that I had to look up to translate, such as neela chand (blue moon) — a festival of true love. However, this detail didn’t bother me because it served as a reminder that this book and this language wasn’t for me, but that instead I should be doing the work of educating myself about different histories and cultures that aren’t valued in the United States. Unlike the other books on this list, Hunted by the Sky is a YA novel and a romance and coming of age story for the 13 year old Gul. However, I still found the setting and the world building of medieval India to be enough to enrapture myself this book, and am looking forward to the publishing of Bhathena’s second book in this duology. Content warning for murder, mentions of sexual slavery, and animal cruelty.

The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water by Zen Cho

Zen Cho’s newest novella is a queer found-family story set in pre-independence British Malaya, and there are instances of revolutionary guerilla warfare against the colonists. It centers around a female protagonist who literally cannot have sex with men, as her goddess would require a cleansing sacrifice in the form of castration. An important note, it is written in the spirit of wuxia traditions but it does not have as much action as you would expect from a wuxia story. However, this is also one of the first wuxia stories I’ve read that also has a very Malaysia setting. The first scene is in a kopitiam—a kind of coffee shop – that has advertisements for soya bean drink and umbra juice side by side. The weapons are traditionally Malaysian, instead of wuxia’s usually Chinese focus. The writing, forms of address, and also words are also in Bahasa Melayu, so definitely have Google handy if you are unfamiliar like me. The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water definitely made me want to do more research into Malaysian independence and the history of Singapore and Malaysia more broadly.

The Poppy War by R. F. Kuang

Of course, I could not leave off the book that set me on my path to read historical Asian science fiction and fantasy. Rebecca Kuang is a PhD student at Yale University in the East Asian Languages and Literatures Department, and has written a fantasy story loosely inspired by modern Chinese history. Despite Kuang’s story being set in a fantasy world, there are very obvious references and parallels to World War II and Chinese literature and culture. The main character, Rin, lives a life that is inspired by Mao Zedong’s rise to power. The first part of the book begins with Rin preparing for the Keju, the Chinese meritocratic test for government office appointment. She has to memorize the classics for the test, including Laozi and Zhuangzi. When she does make it to the most prestigious military academy, she has a strategy class where a student directly references the famous arrow stealing strategy from Romance of the Three Kingdoms—by filling a boat with scarecrows and letting the enemy shoot at it, you can replenish your arrow supply and kill the enemy with their own weapons. And finally, the most horrifying parts of the book are—which I am attempting to describe in the least spoilery way possible—references to Japanese human experiments during WWII and the Nanjing Massacre. Given that I’ve just alluded to a massacre, content warning for graphic depictions of violence in the third part especially. The Poppy War is gripping from the very beginning—I devoured it in a day—and offers a refreshing female protagonist.

Rita Wenxin Wang is a freelance writer based in New York City. She is passionate about Asian Americana, diaspora, and leftist politics. She recommends you read My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness and watch The Handmaiden. When not writing, she can be found on her figure skating stan twitter account interacting with other queers about the superiority of Yuzuru Hanyu’s skating.