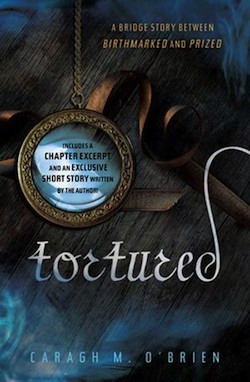

We invite you to enjoy this short story from Caragh M. O’Brien: Tortured. It is available for free download wherever ebooks are sold. Taking place between her novels Birthmarked and Prized, Tortured answers an important question:

“But what about Leon?” Caragh M. O’Brien answers her readers’ most common question with a tale of suffering and determination from Leon’s perspective. Be warned.

(SPOILER WARNING: The following spoils the ending of Birthmarked.)

“I’m not going to fix him up if the Protectorat is just going to have him worked over again,” Myrna said from the doorway of V cell. “I won’t be part of that.”

Leon heard her dimly through a haze of pain, and stirred in his chains.

“If we can get him out of here before Miles changes his mind, it’ll be over,” Genevieve said. “Please, Myrna. You have to help me. Give him something, please.”

Kneeling, Leon lifted his head to see Genevieve, his stepmother, working the catch on the metal cuff that held his left wrist, and then she caught his arm when it fell. She retrieved his white shirt from the corner of the cell and wrapped his hand in the makeshift bandage. He tried to straighten, not to sag his torso’s weight by his other chained wrist, and the doctor, Myrna Silk, came forward to help support him. A second later, he felt a sting in his shoulder, and Myrna withdrew a syringe.

He swallowed thickly, working his dry throat. “Did they find Gaia?” he asked.

“Your father’s searched all of Wharfton and can’t find her,” Genevieve said. “They’ve tracked down her old neighbors and her friends but she isn’t with any of them.”

“So she got away?” Leon asked. If so, it would be the first good news he’d had in four days.

“Yes. So far, at least,” Genevieve said. “Guards are looking for her in the wasteland. Why? Did you think we’d found her?”

“Iris told me at one point that they did. I didn’t know what to believe,” Leon said.

“She’ll have to come back,” Myrna said. “She can’t keep that baby alive in the wasteland.”

His other wrist came loose, and with the lowering of his arm, tiny explosions of new pain stretched across his back. Shirtless, he surveyed his bare arms and torso, finding the raw streaks in his skin where the whiplashes on his back trailed around his sides.

The two women helped him to his feet, supporting his arms over their shoulders.

“Watch his back,” Genevieve said.

“I know,” Myrna replied.

Leon struggled to coordinate his feet, clenching his body as each step triggered pain upward through his muscles.

“Buck up,” Myrna said. “No fainting, now. Hear me?”

He focused all his concentration on the cement floor before him, and then the steps as the women guided him down. Disoriented, he began to fear it was only a nightmare, that they were leading him deeper into the prison or a stone tomb where he’d awaken to another round of torture. His instinct was to struggle.

“Leon, please,” Genevieve insisted. “You’ll be all right, but you have to let us help you.”

“You let them do this to me,” he said.

“I made them stop,” Genevieve said, plainly stricken. “I’ve been pleading with your father ever since I learned he turned you over to Mabrother Iris.”

They reached a tunnel next, and lights that were thinly spaced down the rugged corridor came on one by one as they approached. Though the air was cool, Leon was sweating from effort, and by the time they reached another staircase leading upward, he couldn’t go farther. He sank to the steps, breathing hard, grasping his wounded hand with the other to apply pressure. The fabric was saturating with blood.

“Get Mabrother Cho for me, Myrna,” Genevieve said, urging the doctor onward past Leon. “He’s in the kitchen. Quickly.”

Myrna’s footsteps vanished up the stairs.

“I’m sorry, Leon,” Genevieve said.

Her apologies didn’t interest him. “Tell me what I’ve missed.”

“They’ve focused in on a Wharfton girl named Emily who was a friend of Gaia’s, and she verified that Gaia went into the wasteland.”

“Emily wouldn’t volunteer that information.”

“She was interrogated last night.” Genevieve’s lips tightened. “Miles gave her baby to Masister Khol. They intend to recover the ledgers you stole, unless Gaia took them with her. If she did, they won’t rest until they find her. Does she have them?”

He looked bleakly at the floor between his boots. “I don’t know where the ledgers are.” He’d said it a hundred times in the last few days.

“You must see it’s a matter of the utmost importance,” Genevieve said. “Those records could guide birth parents outside the wall to the families inside who are raising their advanced children. It would cause widespread panic if parents in the Enclave believed that their children could be identified. They’d be afraid their kids could be stolen.”

“Like you’d have cared if my birth parents came for me?” he asked.

“Leon,” Genevieve said. “Of course. You’re my son no matter what’s happened.”

Wincing, he tightened the fabric around his injured hand, even though it was doing little to staunch the blood. The tip of his ring finger had been severed from the knuckle up, and his efforts to arrest the blood flow when he’d been chained had not succeeded. Only the combination of his hand being raised high and his wrist shackle restricting his circulation had prevented him from losing more blood.

“I wish you’d just cooperated with him from the start,” Genevieve said. “Do you know where Gaia is now?”

“No.”

“Or where she’s gone? Didn’t she tell you anything?”

He glanced up grimly. “You think I’d tell you if she did? Now that they’ve found Emily, my resistance didn’t make much of a difference anyway,” he said. “That’s why the Protectorat is letting me go now, isn’t it? He’s done with me. Why doesn’t he just kill me?”

She put a hand on his arm, and he went still at her touch.

“Don’t, Mom,” he said.

“Your father’s never known how to handle you,” she said quietly, releasing him. “But this is the worst of all.”

He didn’t want to hear it. The man had ceased being any decent kind of father long before he’d ordered Leon’s torture. What Leon didn’t understand was why Genevieve was still with the Protectorat. How could any woman stay with a man who hurt his own son? She must not love him as a son, either. That’s what it felt like to Leon, no matter what she said about protecting him. Her lies only added to the betrayal.

He didn’t need this. He had to get out of here. He took a deep breath as the noise of footsteps descending came down the staircase and he shifted. A compact, strong man in a white chef’s apron preceded Myrna past Leon.

“What’s this?” Mabrother Cho said with false levity. “In trouble again?”

Leon looked up to see the cook scowling at his back.

“You don’t seem surprised,” Leon said. “Give me a hand?”

Mabrother Cho stooped instead, and hauled Leon over his shoulder, careful not to touch his ripped back. He carried him up the rest of the stairs into the kitchen, where he gently deposited him on the long wooden table. Leon shifted heavily over the edge to sit on one of the stools instead.

“If I lie down, I’ll pass out,” Leon said, and glanced up at the doctor. “See what you can do, Masister.”

He held out his hand first. The doctor took it tenderly between her hands, turning it carefully, and unwrapped the torn, blood-soaked fabric. “A bowl of water,” Myrna said. “And more so I can wash his back. And towels. This is ridiculous working like this. At least get me better light.”

“I’ll get the lamp,” Genevieve said.

Myrna opened her black satchel and began laying out medical supplies, including a metal scalpel that she propped over a candle flame. She readied another syringe.

“What’s that?” Leon asked.

“Another dose of morphine. It’s going to hurt, what I’m about to do for you.”

He shook his head. “I can’t have it. I have to be able to think.”

Myrna regarded him soberly for a second, then set the syringe and the little bottle of morphine aside. “I’ll send it with you. When you reach the point you need it, you can take it.”

Mabrother Cho returned with a metal bowl of clean water. Genevieve had an extra lamp, which she arranged near Myrna’s shoulder.

“Put the bowl there, and stay out of my way,” Myrna said, directing Mabrother Cho. “You, too, Masister. No hovering.”

Leon was slouched forward, elbows on the table, and when Myrna immersed his hand in the bowl, blood immediately began to seep into the warm water, turning it red.

“You’re reported to have a great bedside matter, Masister,” Leon said. “Where’s that tonight?”

“That’s only for patients I don’t care about,” Myrna said.

Yet when she began cleaning the wound, her touch was gentle and sure. He winced when she snipped away a dangling bit of torn skin, and blotted at the blood with a cloth. Then she hitched the lamp nearer. “It’s a clean amputation at least,” she said.

“Glad you think so,” Leon said. He refused to turn his mind back to how it had happened.

Myrna peered at it closely again, tilting her face as she inspected it from every angle, and then she folded Leon’s undamaged fingers down into a fist, keeping his wounded one extended over a clean towel.

“Mabrother Cho,” Myrna said. “I need you to hold his arm. Here.”

Startled, Leon tensed as the chef pinned his forearm securely against the table.

“You don’t want to watch this,” Myrna said, tightening her grip around his finger.

Before Leon could argue, she took her hot scalpel from over the flame and pressed the flat side of it firmly against his raw fingertip, cauterizing the flesh with a sharp sizzling noise. The sensation knocked Leon backward and he would have fallen except that Mabrother Cho kept his arm pinned to the table. A pungent, burning scent soured the air.

“Thank you,” Myrna said curtly to Mabrother Cho. “You can let him go.”

She set her scalpel aside.

“Are you done?” Leon asked, breathless with pain.

The doctor was frowning in concentration, examining his finger again. “Yes,” she said. “With this at least. Let’s see your back.”

She released his hand. He curled his fingers slowly toward himself, scrutinizing the seared end of his finger. The burned tissue was damaged in a controlled, scarlet burn, the bleeding had stopped, and the skin at the edges had singed to a tender brown. His pulse was still hammering in his veins but the pain, oddly, was deadening a little, as if the nerves to his fingertip, which before had been ragged and shrill, now were short-circuited. The significance struck him for the first time: his wedding ring finger had been deliberately stunted, as if he’d never make a fit husband.

“Ouch,” he said softly.

“Change your mind yet about the morphine?” Myrna asked. “I could put you out for a couple hours.” She put a light dressing on his finger to keep it clean.

“No.” He glanced over at Genevieve, who had gone very pale. “You said he could change his mind?”

She hesitated, then nodded.

“Would he come down here?” Leon asked.

“I don’t think so,” Genevieve said.

Leon heard the uncertainty in her voice. “Can you get together some supplies for me?”

She nodded and slipped quietly out.

He’d been barely aware of his surroundings, but now he glanced around the great kitchen of the Bastion, with its rafters high above and a row of ovens near the open fireplace. A bowl of brown eggs was in a familiar place on the counter, and he remembered a blue ceramic teapot on a shelf by the window. How long it had been since he used to sneak down as a kid to visit the cook he couldn’t recall, but little of it had changed. Though most of the cooking equipment was tidily put away, four pie dishes on the counter were filled with unbaked crusts that draped gracefully over the edges, and he could see a big bowl of apples had been sliced and sprinkled with cinnamon. In fact, now that he looked more closely, he saw traces of flour across the top of the wooden table, and Leon guessed that Mabrother Cho had hastily moved things out of the way to clear room for his unexpected guest.

“Pies?” Leon asked.

The cook gave a shrug. “I couldn’t sleep.”

“I’ll need some food to take with me,” Leon said.

“Where are you going?”

“Into the wasteland. Mycoprotein mainly would be good, and some powdered baby formula,” Leon added. “And whatever you have for canteens.”

“You’re going after the midwife? Do you know where she was headed?” the cook asked.

Leon knew only that Gaia was heading north, and that she had at least a four-day lead on him. Anxiety made him restless.

“Here, hold still,” Myrna said. “What’s this?” She touched the back of his head.

“I was hit there when they arrested me.” He lowered his head to rest on his folded arms, and she cleaned the tender lump on the back of his skull.

“Have any headaches?” she asked.

“Not so bad now.”

As the doctor turned to work on his back, he could feel her cleaning the scabby wounds from his floggings and couldn’t help flinching. He tilted his face, staring blindly at the piecrusts, and grit his teeth. He searched mentally through his body for one place of him that didn’t hurt and settled on the big toe of his right foot. Deep inside his black boot, under the table, that one part of him was okay and he concentrated on that.

Then, after the cleaning was finished, he felt the careful tugs at his back as she sewed the worst of his shredded skin.

“Is that necessary? I won’t be able to reach to take the stitches out,” Leon said.

“They’ll dissolve by the time you heal,” Myrna said.

The little snipping noises continued as she tied off the knots, and finally she set aside the curved needle and scissors on the towel in his line of vision. Mabrother Cho brought him a bowl of barley soup to drink. Leon couldn’t relax, couldn’t let down his guard against pain, but he swallowed the salty, steamy liquid and dipped a crust of the bread in the dregs to swab them up.

“More?” Mabrother Cho asked.

Leon nodded.

“Hold still,” Myrna said again.

Next he could feel the doctor dabbing something on his back, a light, cool substance that pulled some of the pain away.

“That’s good,” he muttered.

She kept at it, working her way from the top, and in the path of her touch, he felt the merciful easing of pain across the back of his shoulders, toward the middle of his spine, and then outward.

“What is that you’re putting on?” he asked.

“The sort of thing your girl would appreciate. It’s mostly an antibiotic, but I added some tansy she told me about. That’s what’s soothing. I’ll give you some of this to take with you, too.”

“You called her ‘my girl,'” he said, surprised.

“Isn’t that why you’re going after her?”

He shifted slightly. “Did she ever talk about me?” he asked.

“Not much,” Myrna said. “She liked the orange. That was from you, wasn’t it?”

“Yes,” he said.

“I guessed as much.”

He would have appreciated a little more to go on, but then, Gaia herself had never been particularly forthcoming. She was the most direct, fearless person he’d ever known, except where admitting her own feelings was concerned. At least, he hoped she had feelings for him. When she’d said that thing about respecting him, as if that was all she did, he’d been startled by how much it hurt, like a clean gouge right through him. Still, she’d gone on to let him kiss her, and that counted for something.

He wanted Gaia to trust him, or more exactly, he wanted to be a person that Gaia would trust, even if no one else ever trusted him. He wondered if she realized he’d risked his life for her. Not that it mattered. He’d have done it anyway. But still, he wondered.

Why did he want so badly to be with her?

“Look at me,” Myrna said, sitting down beside him on another stool. Her fingers were still smeared with the frothy, white salve.

He looked up doubtfully to meet her gaze. Myrna’s shrewd eyes were devoid of sympathy, but he could see that didn’t make her heartless.

“Don’t ever blame Gaia for this,” Myrna said.

“I don’t.”

“No. I mean later. Whether you ever find her or not. None of this was her fault.”

“I know,” he said. “It was my decision. I knew what could happen to me. I know what could happen to me in the wasteland, too.”

Myrna rose to rinse her hands at the sink, leaving Leon to rest another minute. His one comfort was that he’d succeeded in helping Gaia escape. He could only believe she was surviving somewhere, somehow. A girl who could come out of prison stronger than she went in, who let hardships deepen her rather than rigidify her thinking, had to be able to handle the wasteland, and as long as she was alive, there was a chance he could find her.

Genevieve returned with an assortment of supplies and a rucksack. “You can’t carry anything on your back, obviously,” she said, “but is your neck all right? You could hang something around your neck, in front of you.”

He lifted a hand to gingerly touch the nape of his neck, which was unscathed. “That’ll work,” he said.

“I think this will keep the sun and flies off your back without clinging,” Genevieve added. She’d brought a loose, lightweight shirt and a bowed oblong framework that he recognized from a kite kit his brother Rafael had owned once. She clipped the framework to the inside of the shirt collar so the material would drape loosely behind him, not touching his skin. The resulting contraption had a flimsiness he doubted, but she tested its spring with a tug, and it rebounded in a way that was flexible and durable enough to last, at least for a while.

“Feeling any better? That first dose of morphine should have kicked in,” Myrna asked, taking the stool again.

He was.

The food was helping, too. Mabrother Cho handed him another bowl of soup and more bread. Then he set before Leon a saucer with a few of the cinnamon-and-sugar-coated apple slices. “You always liked these,” he said.

Leon looked up, noting the cook’s kindly expression.

“You know each other,” Genevieve said, as if she were just figuring that out.

“More or less,” Mabrother Cho said, smiling. “He used to sneak down here nights when he was little, now and again. Your boy here’s made lots of friends I suspect you’ve never known about.”

Leon reached for an apple slice and bit into the sweetness. “Not so many,” Leon said.

“Enough that you’ll be missed,” Mabrother Cho said. “Don’t be gone forever, Mabrother.”

Leon didn’t know what to say. He had no idea what he might find in the wasteland or if anything lay beyond it. It seemed unlikely he’d ever come back. He watched while his mother and Mabrother Cho packed food and supplies in the pack: mycoprotien, dried fruit, cheese, a little tea, flatbread, and a canister of baby formula. They added matches, a candle, flint and steel, a small pot, and a knife. Mabrother Cho filled four lightweight, metal canteens, capped them, and looped them to a sturdy belt.

How many supplies had Gaia taken? Leon wondered. How long could she last on what she could carry? And she had the baby, too. The thought made him impatient to leave.

“You want a blanket?” Genevieve asked. “It’ll get cold at night when the sun goes down. I can pack it small.”

“All right,” he said.

“A hat,” Myrna said.

“I have one here,” Genevieve said, offering a beige one with a wide brim.

Myrna showed him where she was putting medical supplies in the outer pouch of his pack. “Your back will start to itch when it’s healing,” she said. “You won’t win any prizes for enduring the pain. Use the morphine, and keep up with the antibiotics.” She shook a small container. “Two pills a day until they’re all gone. Promise me.”

He lifted the bottle to eye the contents. “If I outlast them.”

“Don’t say that,” Genevieve said.

He glanced across the table to her. His mother stood with her shoulders proudly straight, but he could see the fear and stress in her troubled gaze. He accepted her help with putting on the shirt, which billowed slightly behind him. Then he dipped his head into the strap of his pack, straightening to lift its weight and shift it to the most comfortable place along his chest.

Genevieve reached for the water belt and slung it over her shoulder. “I can take this as far as the wall for you.”

He didn’t argue with her. Donning his hat, he took a last glance down at the table with its bowl of reddish water, the dirty towel, and Myrna’s tools. Myrna was regarding him gravely, but she held out a hand to shake his.

“Good luck,” she said simply.

Mabrother Cho lifted a hand in silent farewell.

Strangely moved, Leon reached past the cook to snag a last slice of apple from the bowl. “Thanks,” he said.

The cook gave a twisted smile. “Get going, then.”

Leon followed Genevieve out the back door of the kitchen, past the rubbish barrels and the empty crates left from deliveries. The night was edging toward dawn, and Genevieve’s white sweater was visible as muted gray over her slender form, sliced by the black of the belt and canteens over her shoulder. As they headed uphill, side by side through the dim, cobblestone streets, he watched warily for guards, still not trusting that he was safe with his mother. The open space of Summit Park was quiet except for a lone cricket, and from that elevation, the high point of the Enclave, he had a view out toward the wasteland, where the horizon was visible as a line of gray meeting with faint pink above. Vast seemed the wasteland, and trackless. Finding Gaia was going to be nearly impossible.

The alternative was staying in the Enclave and waiting for the moment his adoptive father decided to put an end to him once and for all.

They left the park and headed down the last curving streets. The occasional streetlights flickered on as they approached, triggered by sensors. At one corner, a mute camera was aimed at the intersection.

“He’s watching us go, isn’t he?” Leon asked.

“Yes,” Genevieve said. “He’ll paint you as a coward and a traitor, but you’ll be safe. You’ll be gone.”

He glanced at her profile. “He can’t be very happy with you,” he said.

“I’m not very pleased with him, either,” she said, and smiled. “Don’t worry about me.”

He considered that. “I will, though.”

She laughed briefly. “Just so you know, Emily turned in the ledgers tonight. I just heard, when I was gathering your things.”

“Did they give back her baby?”

“No. Miles advanced the baby. He thinks she had a copy of the birth records made. She had enough time.”

Leon stared ahead to where the wall that surrounded the Enclave was coming into view. Gaia’s friend Emily must be frantic about her advanced son, and she’d be helpless against the injustice of the Enclave. He was glad Gaia didn’t know, for he was certain she would blame herself if she did.

“See what you can do about that,” Leon said.

“I will. I’ll try. But we also need to be sure our children are secure.”

“It proves Gaia didn’t take the ledgers with her,” Leon said.

“I know.”

“So will he call off the search for her?”

“That I don’t know. She’s still a criminal for stealing them in the first place,” Genevieve said.

“Advancing the babies in the first place, though,” he said dryly. “That doesn’t count as theft?”

“You know it doesn’t,” Genevieve said. “That’s completely different.”

“Tell that to Emily.”

“No, you think it over yourself,” she said, “and imagine what your life would have been like if we hadn’t raised you.”

He laughed bitterly. “You can still say that, when my father has just had me tortured for four days?”

She paused, and he was compelled to turn beside her. “I’m not going to try to excuse him,” she said. “But can we not argue about him? Just for now?”

He could make out her eyes enough to see how troubled she was. His feelings for her were confused by the bitterness he felt towards the Protectorat and her own complicity in his cruelty. On the other hand, she was likely the only one in the Enclave who had the power to save him from his father, at what personal cost to her own well-being, he couldn’t guess. He couldn’t stay hardened against his mother, not when they only had a few more minutes together.

“All right,” he said.

“Thank you.”

The North Gate, seldom used, was smaller than South Gate but it, too, was patrolled by the requisite guards. They nodded at Genevieve as if expecting her, and when they opened the tall wooden gate, Leon passed under the arch to the outside. He glanced behind him for the last time, at the quiet, tree-lined street and the lightless towers of the Bastion, just visible over the rise of the hill.

Before him, the hill sloped down toward an arid, windswept, shadowed landscape of boulders and stunted brush. His future. The cold uncertainty of it chilled him, and yet he did not look back again. The likelihood of finding Gaia’s tracks was essentially nil. He could scan for movement by day, and at night it was possible a campfire would show to guide him to her, but probably his best chance was to head north, looking for civilization, and hope Gaia found the same place.

He briefly considered circling back to ask Emily what she knew of Gaia’s departure, but it would be risky, and set him back several hours, and he already knew Gaia intended to head north for the Dead Forest. If it existed. Gaia believed it did.

I’ve done smarter things than this, he thought.

Wordlessly, he took the belt from Genevieve, settling it around his waist so that the canteens rode to the sides where they wouldn’t impede his stride.

“Here. One last thing,” she said, and passed him an extra roll of socks. “For your feet,” she added, as if he didn’t know. “It’s important to take care of your feet when you’re going so far.”

The ball was soft in his hand. “Mom,” Leon said, strangely moved.

“I’m just so sorry about this. If there were any other way—”

He shook his head, and pulled her near to hug his arms around her. She couldn’t hug him back properly because of his wounded back, but she held tight to his collar and kissed his cheek.

“Please be safe,” Genevieve said.

“I will. Give my love to Evelyn and Rafael,” Leon said.

“Come back to us,” she whispered.

There was no answer to that. For a last, long moment he held her, filling with sad tenderness, a kind of forgiveness and loss that normally would have made him feel weak. Instead, he felt human, honest. “I’ll miss you,” he said, and knew it was true, despite everything.

When he left his mother and started down the hill, he trod carefully in the shadowed space between boulders. He hitched once at the belt around his hips, tucked the socks in his pocket, and began his vigilant search for motion along the horizon. Somewhere ahead of him, Gaia was traveling with her baby sister. Whether what he was doing was stupidly reckless or nobly brave didn’t much matter, because the only thing left to do was try to find her.

Copyright © 2011 by Caragh M. O’Brien