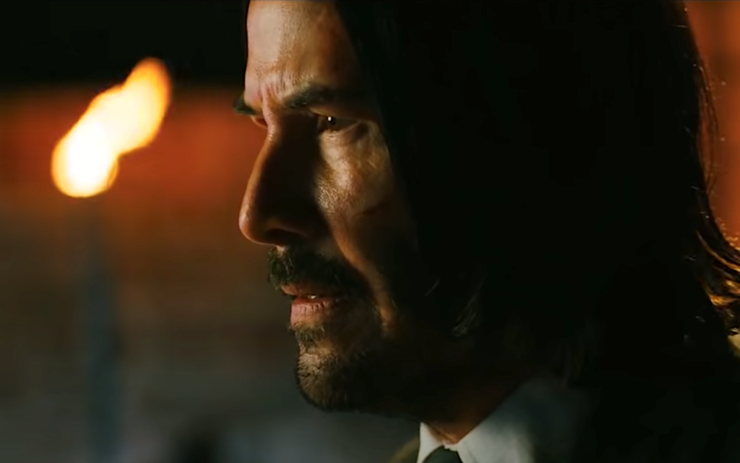

The first John Wick begins as a film we’ve seen many times before. A hitman has retired. He was drawn into “normal” life by love, and for a while he had a house in a suburb, drove his car at legal speeds, and went for romantic walks with his wife. The two of them probably had a takeout night, and a favorite Netflix series. But, as in all of these kinds of movies, the normal life is a short-lived idyll, violence begets violence, and the hitman is Pulled Back In.

The thing that makes Wick so beautiful is that what he gets Pulled Back Into is not the standard revenge fantasy. Instead being Pulled Back In means literally entering another world, hidden within pockets of our own. Because in addition to being a great action movie, John Wick is a portal fantasy.

While subtle, John Wick’s entry into his fantasy world is not unlike Dorothy Gale’s—where she is sucked up by a tornado and comes to the Land of Oz after saving her dog Toto from Miss Gulch, Wick crosses an invisible line back into the world of assassins because a Russian mafia scion kills his puppy, Daisy. (I’ll admit I’ve never seen this scene. I leave the room until it’s over and then come back in to watch the part where he murders everyone in memory of his dog.) Like with any great portal tale, each chapter reveals more of the Wickverse, and the story’s ties to realism become more tenuous.

The first film obeys the rules of a standard action film with only occasional hints of a larger, more mythical world (the character names, for instance), but Wick 2 and Parabellum get weirder and weirder until it’s clear that this is a world that operates by its own internal logic—and as with Oz, the Wizarding World, Narnia, or London Below, the magical world has a much stronger pull than the mundane. Like all portal fantasies, the audience has a guide to the world. In this case instead of a character fall in love with a new realm—Harry tasting his first Every Flavor Bean, or Lucy meeting a gentlemanly faun—we get John Wick, a grieving hitman who is literally world-weary. He knows this Underworld, and he hates every inch of it. Instead of watching Alice learn the rules of Wonderland, or Richard Mayhew get a new angle on the meaning of “Mind the Gap”, John, for the most part, shows us the rules by questioning and fighting against them. The Wick films live in the tension between showing us a fascinating world and suggesting we should take John’s advice and get out while we still can.

Holy Ground

One of the few institutions he seems to respect, however, is our first stop in the Underworld, The Continental. It seems like a regular (if posh) hotel whose management is willing to cater to the specific needs of assassins. But when we get a glimpse of the administrative office, whooshing with pneumatic tubes and staffed entirely by tattooed femme rockabilly devotees, we begin to see that it has its own history and rules within the Underworld. The Continental operates under a strict “No Assassinations on Premises” policy, making it the Underworld’s de facto Switzerland, and we learn how serious that rule is: after Ms. Perkins, an assassin and Continental member, attacks John in his room, she is told her membership has been “revoked” and is summarily executed.

But starting with John Wick 2, it becomes clear that The Continental is every bit as magical as Hogwarts or Brakebills. Just as the worlds of the Harry Potter series and The Magicians have magical schools dotting the globe and participating in exchange programs, so The Continental has branches scattered throughout its world. In the second film, more of The Continental’s services are revealed when we meet The Sommelier, the dapper weapons expert who outfits John with a tasting menu of guns, knives, and incendiaries, and Doc, who patches people up. Those tattooed pneumatic tube operators keep tabs on the assassins’ whereabouts and open contracts by posting fees on a chalkboard, and announce people’s status as “Excommunicado”—i.e., banished from the sanctuary of The Continental, and vulnerable to murder—through deadpan intercom announcements that sound like nothing so much as boarding times in an old timey train station. It’s this tone that creates the feeling of magic. The Ladies are calm and efficient; Charon, the Concierge, is courteous and dapper; Winston, the Manager, is utterly impossible to flap. This creates another delicious gap between their behavior within the hotel and the horrific murders that occur outside its walls.

The assassins’ world doesn’t have anything like floo powder or portkeys (so far) and as far as we know John can’t transform into a goose (although oh my god put John Wick: Untitled Goose Game in my eyeballs immediately, please) but once John Wick ventures beyond the U.S., the films use the magic of editing to make it seem as though he can simply appear in the Italian or Moroccan Continental—we never see any TSA agents, bloodshot eyes, or awkward neck pillows. All branches of The Continental observe the same code of discretion, seeming to operate as fiefdoms under the local authorities of their leaders (Winston, Julius, and Sofia, so far, but presumably there are others) and those leaders report to the central authority of The High Table. The only tiny caveat to this hierarchy the films have offered so far comes when Julius, the Manager of Rome’s Continental branch, asks John if he’s come for the Pope—which opens up its own series of questions: are there people above even The High Table’s authority? If so, is The Continental authorized to stop assassins from hunting those people, and if that’s true, how does one get on that list? Or is Julius simply a good Catholic and/or fan of the Pope, and chooses to break his own hotel’s Rule to ask John his business?

Another part of Wick’s world becomes clearer in his trips to the various Continentals: Just as the entire Wizarding World runs on gallons, sickles, and knuts, and just as London Below has based an economy on a byzantine system of favors and debts, Wick’s Underworld uses its own currency that is self-sufficient and separate from our world’s economy.

Talismans as Currency

After John’s shot at a new life is taken away, he prepares to return to the Underworld by digging up the money and weapons from his old life. We see him sledgehammer through his house’s foundation to unearth a chest of coins and a cache of guns—a literal buried treasure of gold and weaponry that are the foundation of his “perfect” life, that, in one image, rivals Parasite for its layered symbolism. Here again, the movie veers away from the typical action movie script to head into a fantastical realm—plenty of action movies feature secret arsenals, but gold coins?

John uses a Coin to rent a room at The Continental, and offers a Coin to another assassin, and a few of the assassins talk about contracts and payments. But we get no sense of what the Coins are actually worth, no amount in USD, euro, or yuan. As we learn in the second film, this is the treasure he earned completing “the impossible task” in order to start a life with Helen. (Did she know what was down there?) And while the coins certainly function as currency in this world, they also serve as talismans—something that first becomes clear when John drops a coin into a homeless person’s cup, and that man turns out to be part of a spy network run by the Bowery King, who we’ll talk about in a few paragraphs.

Wick 2 also introduces us to “Markers”—larger coins imprinted with bloody thumbprints. These are catalogued in an enormous bound ledger of complementary thumbprints that record the history of debts and balances in the Underworld. If someone does you a favor, you prick your thumb and press it on the coin, binding yourself in an oath to repay them. Once they cash the favor in, their thumbprint is pressed into the book, showing that you are once again free of debt. They’re elegant—and utterly unnecessary. Why not simply write the debts down and sign them? Why not use a Google doc? Why the blood? The Markers seem to be as binding as The Continental’s hospitality mandates, and when someone cashes one in, you must comply. This is another rule that Wick tries to fight when he refuses to honor Santino’s Marker, and we learn how seriously the world takes them when Santino goes straight from “I’m asking politely” to “Fine, I’ll blow your house up with a rocket launcher” without attracting any censure from the rest of the assassin community.

Parabellum adds another talisman to the Coins and Markers. John passes a regular Coin to a cabbie to buy Dog safe passage to The Continental—thus revealing another layer of New Yorkers who are in on this alternate universe—but once his sentence of Excommunicado kicks in, he calls on a new icon for help. Like many a fantasy character before him, he seeks refuge in the library, in this case the New York Public. He retrieves a hollowed-out book from the stacks, and opens it to find more Coins, a Marker, the inevitable grief-inducing snapshot of Helen, and a large crucifix threaded on a rosary. After using a book to defend himself against a fellow assassin (so close to the gritty Hermione Granger spinoff I’ve always wanted) he takes the rosary to the Director of the Ruska Roma, and uses it to demand their help. This type of Marker isn’t part of the larger Underworld, it’s only a form of currency among the inner circle of Belarusians and John, as their adopted child, is owed a debt of obligation. Does this mean that each subgroup within the Underworld has their own Talismans?

Just like the other Markers this one is sealed with pain: one of The Director’s assistants brands an inverted cross into the Virgin Mary tattoo on John’s back—which is going a little far even for me. He emerges from this deeper Underworld back into the regular Underworld of assassins, using a standard Marker to press his old frenemy Sofia into helping him. Meanwhile, we see The Adjudicant slide a standard Coin to Charon to let him know that they are there to investigate Winston, and they later claim that the High Table’s form of currency outranks all others by punishing The Director for helping John, despite his seemingly correct use of the Crucifix Talisman. The fact that John was operating within the bounds set by his Markers is irrelevant compared to his status as Excommunicado, an idea underscored by a long weird digression in Morocco, where we meet Berrada, the keeper of The Mint.

Rather than showing us a scene of gold being melted down and pressed into molds, or of accountants tallying up ow many Coins have been minted, we meet Berrada in a garden, where he shows John the First Coin, preserved as a piece of art. The Coins are the foundation of this Underworld, they are part of its origin story, and Berrada shows us their importance by speaking about them not as currency but as symbol: “Now this coin, of course, it does not represent monetary value. It represents the commerce of relationships, a social contract in which you agree to partake. Order and rules. You have broken the rules. The High Table has marked you for death.”

True Names & Gender Shenanigans

The idea of people and objects having “true” names they keep hidden, and public-facing names for everyday use, pops up all over the fantasy genre. This trope dovetails nicely with the idea that professional assassins would probably also have a few aliases tucked into their back pockets, but the Wick movies take this to mythical extremes.

We’re given clues that we’re in a fantastical universe right away. Helen, John’s wife, is named fucking Helen—not such a tell on its own, but once you add her name to all the other characters, you see a story bristling with allusions to Greek and Roman mythology. A man named Charon guards a liminal zone between the violent outside world and the neutral territory of the Continental Hotel. John battles bodyguards named Cassian and Ares, is aided by a woman named Sofia, and fights a fellow assassin named Zero.

Buy the Book

Over the Woodward Wall

But most telling, John himself has gone by three names so far. His common name is John Wick, simple, anglicized, it starts soft and end in a hard “ck” sound. There’s the fact that “John” is a plain male name, and that “wick” might imply a fuse or a fire, but a wick itself is harmless unless someone chooses to light it. In Wick 2, the trip to the Ruska Roma reveals a name that might be more “true”: Jardani Jovonovich, seemingly the name he was given as an infant in Belarus.

But even more fascinating is the third name: Baba Yaga. When the subtitles call him “the boogeyman” what the characters themselves are saying is “Baba Yaga”. Which is interesting, because while Baba Yaga is sometimes a woodland witch, sometimes a sorceress, and sometimes a force of Nature or a type of Earth Goddess, she’s also described as female—or at least as choosing to take a female form. So why is this the name assigned to John Wick? Why not some other terrifying figure from folklore?

My guess is that John Wick is hinting, as many fairy tales and fantasy stories do, that gender is fluid, and that the deeper we get into the Wickverse the less it matters. This is underscored by the trajectory of other gender roles: in the first film boisterous young Russian men cavort in private pools with bikini-clad women, and the one female assassin we meet purrs and growls all of her lines at John in a way that made me think they have A Past. But in Wick 2 John goes up against Ares, who is played by the genderfluid actor Ruby Rose. Ares, named for a male god, is hypercompetent, ridiculously stylish, and androgynous—but never seems to be defined by gender at all. They’re the right-hand person to Santino, and they command an army of assassins who all seem to be men, who never question their judgement, second-guess their decisions, or repeat their ideas, but louder. Gender is simply a non-issue, which is a breath of beautiful air in the action genre, when even the Fast & Furious franchise tends to adhere to certain gender stereotypes. In Parabellum John is pursued by assassins of various genders, signifiers, and fighting styles, but again, none of them uses any of the femme fatale shenanigans practiced by Ms. Perkins in the first film.

John only survives Parabellum at all because he calls in his Marker and asks for help from Sofia, the Manager of Casablanca’s Continental. Here, too, the film sidesteps the pitfalls common to its genre. First of all, as Management Sofia outranks the heck out of John. But the real twist is that he earned a Marker from her when he smuggled her daughter out of the Underworld. So here we have a late-middle age woman, a mom, who is respected absolutely in her role, and defined by her competence. The only person who steps out of line is Berrada, but he’s also her former boss, and more important he intentionally hurts a dog, so according to the Wickverse (and all right-thinking people) he’s pure evil.

Parabellum also introduces The Adjudicator, played by the non-binary actor Asia Kate Dillon, who represents The High Table and is probably the second most powerful person the Wickverse has given us so far. Here again gender just doesn’t come up—because why should it? But it’s interesting to me that compared to most action films that weave sex and violence together, and play with images of “bad” women or “sexy female assassins”, the latest two Wick movies seem to be ignoring stereotypes, and even stepping outside of the gender binary entirely in a way that recalls stories of Tiresias, Poseidon, and Loki.

Hierarchy

What’s a standard hierarchy in an action movie? If there’s a criminal outfit, it’s usually divided into underlings or henchpeople, people who are pure muscle, people who have specialties like accountancy, driving, mechanics, or tech, trusted right-hand people, and several levels of “boss” leading up to the Capo, Kingpin, Godfather/mother/person—whatever the Biggest Bad is called. On the Lawful Good side of the equation there might be cops and lieutenants, detectives and federal agents, D.A.s and judges. Generally there is some sort of ranking system at work, so that as the protagonist works their way through a heist or bank robbery or a court case or mob war, the audience will get a sense of their progress.

This is another thing that, for the most part, the Wickverse gleefully chucks out the window. In the first film, John seeks vengeance on a Russian mob boss’ son, but with the exception of Dean Winters as the boss’ right-hand man, the goons are all equal in their goon-hood. And when John gets pulled back into the Underworld in Wick 2, all the assassins are freelancers. They get texts with job offers, and they decide whether the offer is good enough for them to deal with the paperwork and self-employment taxes. Because of this, as the movies unroll and more and more assassins come out of the woodwork, you never know which ones are going to be formidable opponents and which ones can be taken out with a quick neck-snap. It destabilizes everything, because John could actually die at any moment. (I mean, probably not, since his name’s in the title—but in the world of the films there isn’t a sense that he’s working his way up through ranks of increasingly deadly adversaries.)

In the first film, and for at least part of the second, the only hierarchy seems to be that everyone obeys the currency of Coin and Marker, and respects the rules of The Continental. It isn’t until John passes a coin to a homeless man and reveals the spy network of The Bowery King that we get a sense that there are other layers beyond the hotel franchise.

Who is the Bowery King? And what sort of assassin’s world is this that traffics in kings and fiefdoms? With the Bowery King we get an updated version of Neverwhere’s Marquis de Carrabas, and, really the entire world of John Wick seems to be in many ways a bloodier take on Neil Gaiman’s classic urban portal fantasy. When John is pulled back into his violent old life, he seems to become invisible to folks who are outside of his world. His house is taken out by rocket launchers, yet he’s able to walk away rather than filing any sort of paperwork with the police. He travels freely to Italy and back to New York. He’s even able to have a shoot-out and a knife fight across a subway platform and train—without any of the regular commuters batting an eye. (And yeah, New Yorkers have seen everything, but in my experience we do notice knife fights.)

It begins to seem like John himself is almost invisible, or like people’s eyes are sliding right past him the way Londoner seem not to see Richard Mayhew and Door. But it’s when John follows the homeless man down to the Bowery that the Wickverse reveals itself to be a close cousin to London Below. The King comports himself like a character in a fantasy world: he expects absolute loyalty, he pronounces and pontificates where others speak, he communes with his pigeons—again, both a widely-reviled animal and an archaic means of communication, and he does all of it with twinkly eyes and a smirk that seems directed straight over John’s head, meant instead for the audience who is either freaking out that Morpheus just showed up, or freaking out that he’s obviously riffing on Neverwhere. (Or, in my case, both.) This idea that there are small kingdoms and hierarchies give even more weight to the authority that stands above all: The High Table.

When The Director of the Ruska Roma questions John’s motives, she talks about The High Table not as a coalition of mob bosses, but in nigh-supernatural terms: “The High Table wants your life. How can you fight the wind? How can you smash the mountains? How can you bury the ocean? How can you escape from the light? Of course you can go to the dark. But they’re in the dark, too.”

And when Berrada tells John Wick how to meet with the Elder, the man who sits above The High Table, these are his instructions: “Follow the brightest star, walk until you are almost dead, then…keep walking. When you are on your last breath, he will find you. Or he will not.” And of course, what is the star John follows? Canis Minor. And so we’re back, in a sense, to Daisy, his emissary from The Other Side. (This also serves as a fun callback to Keanu’s side gig as a bassist in a band called Dogstar, but I don’t know if that has any relevance to the current thread.) These are not the kind of directions you’d give to Dom Torretto, or Jason Bourne, or John McClane, or any Jason Statham character ever. There is no street address here, no building to break into, no organization to infiltrate. This is pure fairy tale logic—but John does it without hesitation. (There’s a gunfight, of course, but he doesn’t hesitate in traveling into the desert in his black-on-black suit and walking until he collapses.)

He meets with The Elder, who reacts to John not with the usual astonishment at his tenacity or his deadliness, but with a deceptively simple question: why does he want to live? And John’s answer is not an answer I expected to hear in what is, ostensibly, still an action movie.

He wants to live so he can have more time to mourn his wife.

He doesn’t think he deserved the new life he had with her. He’s willing to live a half life in the Underworld he hates in order to keep her memory alive a few years longer. When The Elder demands fealty, John doesn’t slash his palm or take a gunshot to prove his loyalty. Told to give them a sign of his devotion, he goes for the most symbolic thing he owns, chops his ring finger off, and give the Elder his wedding ring. This, to me, is a HUGE misstep. Having been pulled back into the Underworld, John is now giving up one of his last talismans of Helen to bind himself to the world of violence forever. This is not a good move in a fantasy story. Do you want to be a Ringwraith? Cause this kinda shit is how you get stuck being a Ringwraith. Luckily for my unhealthy emotional attachment to a ruthless killer, the Wick franchise doesn’t spend too much time on the complexity of this move. John fights his way back to the New York Continental and parleys with Winston, who always know just what to say, and deploys two of John’s many names to get his attention:

“The real question is, who do you wish to die as? The Baba Yaga? The last thing many men ever see? Or as a man who loved and was loved by his wife? Who do you wish to die as, Jonathan?”

And of course Winston betrays him and shoots him off a roof, and John, like a good fantasy hero, survives against all the laws of medicine and physics, and yes there’s a hint that Winston was only pretending to betray him, and yes the film’s final scene sets us up for a Wick/Bowery King team-up where the two of them are going to declare that THIS WHOLE HIGH TABLE’S OUTTA ORDER.

And that will be amazing.

But the fascinating thing to me is just how much the Wickverse throws caution to the wind and takes the action genre into the realms of fairy tale, fantasy, and myth. Most portal fantasies end either with the protagonist going home, at least temporarily, or building a new home in the new world. (Or with a theologically-problematic trainwreck, but I’m not getting into that right now.) Plotwise, John Wick: Parabellum ends with the promise of a new adventure. But emotionally I would argue that the film culminates in this moment of metaphorical homecoming, when John chooses to be the man whom Helen loved, rather than either Baba Yaga or a dog on the chain of the High Table. My hope is that the next film pushes the fantasy themes even further, shows us new corners of the Wickverse, and finally just commits and sends John to another realm entirely. Think of the fun he could have in Narnia.

Originally published in April 2020.

Leah Schnelbach is excited for John Wick’s next adventure, especially if it culminates in John opening a no-kill dog shelter. Come have a civilized chat in The Continental that is Twitter!