“The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” So runs one of William Blake’s Proverbs of Hell. Judging from his novel Hollow, Brian Catling, who made Blake a character in his earlier Vorrh Trilogy, seems to have taken the poet’s infernal proverb to heart. He has followed Blake’s path as far as it goes: Everything about this novel is excessive, sometimes ludicrously so, but it achieves an ungainly beauty and a crooked wisdom.

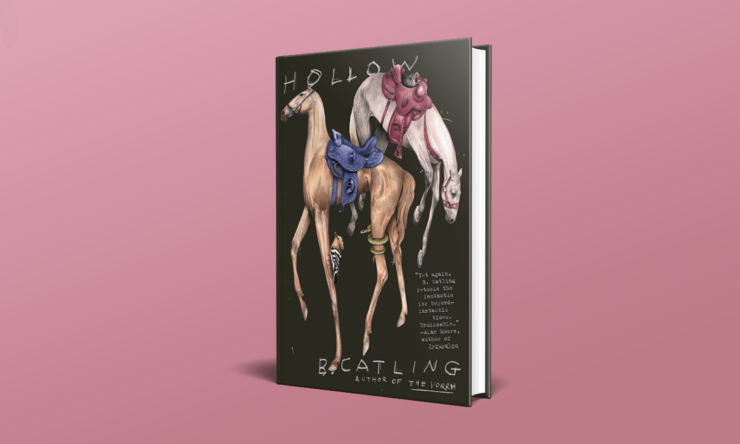

Brian Catling, stylized “B. Catling” on his book covers, first came to genre readers’ attention when Alan Moore wrote an introduction to The Vorrh, which he labeled a “landmark work of fantasy.” Two further novels concluded the story begun in The Vorrh. Hollow is the first Catling novel to receive wide U.S. distribution since the trilogy’s concluding volume.

In some version of 16th century Europe, a band of brutal mercenaries is transporting a misshapen and inhuman Oracle (always capitalized) to a monastery at the base of Das Kagel, the vast terraced mountain that once, perhaps, was the Tower of Babel. To sustain the Oracle and prepare it for its eventual immurement in the monastery’s Cyst, the mercenaries, all old in evil, must whisper their darkest secrets to a box of bones. Once Steeped in confessed wickedness, the marrow from the bones may be fed to the Oracle. At the monastery, young Friar Dominic has his voice mysteriously stolen, while the abbot conducts mysterious research on demons and spends days in the Glandula Misericordia, which is the vale, protected by the abbey’s walls, that encompasses “three square miles of confined isolation in which rages a perpetual war between the living and the dead,” a horrifying sight that “is not a manifestation of evil but the workings of the mind of God.” Finally, a prematurely old woman, Meg, sometimes called Dull Gret, finds herself leading a crew of impish familiars against a corrupt constabulary.

Buy the Book

Hollow

Brian Catling made his name as a sculptor, painter, and performer; his first novel did not appear until he was in his sixties. Artists figure prominently in his earlier books; William Blake was a central figure in the Vorrh stories, as was the unstable photographer Eadweard Muybridge. Catling is a visual writer; at times, reading one of his novels feels like strolling through a vast gallery of paintings Catling would have liked to have painted. The presiding artists of Hollow are Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Hieronymus Bosch, masters of Northern Renaissance painting. Bruegel is only named in the book’s acknowledgments, but Bosch’s paintings play a role in the book’s plot; the imps invading the monastery have, somehow, sprung from Bosch’s canvases into the book’s reality. Bruegel’s influence is felt in the setting of Das Kagel; an ivory-painted miniature glimpsed by Follett is a version of Bruegel’s Tower of Babel. Later, the mercenaries glimpse The Hunters in the Snow returning to their village and Meg skirts around The Battle Between Carnival and Lent. It’s no wonder that Meg should befriend the Boschian imps she encounters; she too steps out of a painting.

When Friar Dominic and his cranky mentor Friar Benedict at last stand awed before a Bosch painting, they are accompanied by Presbyter Cornelius, an educated philistine who intellectualizes art without appreciating it. Cornelius describes the painting in these terms: “The rendition of the phantasmagorical far exceeds all the artist’s stylistic works, a positive ascent into stylistic maturity. Pay attention to the brushmanship; a sharper, terser touch, with much more command than before. A mastery of fine brush-point calligraphy, permitting subtle nuances of contour and movement.”

Bosch’s works, with their precise details, meticulous observations, and trompe-l’œil effects, attempt to link the artist’s vision and the viewer’s mind; Bosch triumphs the moment we forget we’re seeing a painting and imagine we’re seeing a world. Despite all the homage he pays to Bosch and to Pieter Bruegel the Elder in Hollow, Catling’s aesthetics are entirely different. Working with words where his heroes employed brushes, Catling forever reminds us of the artificiality of his words. He has no desire to vanish behind his narrative’s canvas; his jagged syntax and expressionistic phrasing jolt and jar. The dialogue is consistently inconsistent; the mercenary Follett and his companions mix “thees” and “thous” with obscenities when they speak, while other characters talk in a contemporary register. There’s something to raise a copyeditor’s eyebrow on most every page of the novel, but these infelicities imbue the book with a knotty vigor that a more mannered book would lack.

Were Hollow merely the catalog of grotesqueries that a plot summary reduces it to, I’d still applaud it for its sheer prodigality with wonders: Each chapter offers the stunned reader a new marvel. But Hollow also offers reflections on the relationship between art and life, and, perhaps more pressingly, between death and art. It’s a tribute to long-dead geniuses that will also thrill readers entirely ignorant of European painting. The word “hollow” suggests emptiness and deprivation, but Catling’s is full to bursting, abundant in wonder and replete in mysteries. It astounds and it appalls. Hollow is the strangest, most original, and most satisfying fantasy I’ve read in ages.

Hollow is available from Vintage.

Read an exerpt here.

Matt Keeley reads too much and watches too many movies. You can find him on Twitter at @mattkeeley.