We are the product of the books we read as children and young adults. They shape the vocabulary we use to shape the world we live in: they spark interests and ideas and ideals that we may never be consciously aware of harboring. Sometimes we’re lucky. Sometimes we can point to the exact moment where everything changed.

I was fourteen. I read like books were oxygen and I was in danger of suffocation if I stopped for more than a few minutes. I was as undiscriminating about books as a coyote is about food—I needed words more than I needed quality, and it was rare for me to hit something that would actually make me slow down. It was even rarer for me to hit something that would make me speed up, rushing toward the end so I could close the book, sigh, flip it over, and start again from the beginning.

I liked fairy tales. I liked folk music. When I found a book in a line of books about fairy tales, with a title taken from a ballad, I figured it would be good for a few hours.

I didn’t expect it to change my life.

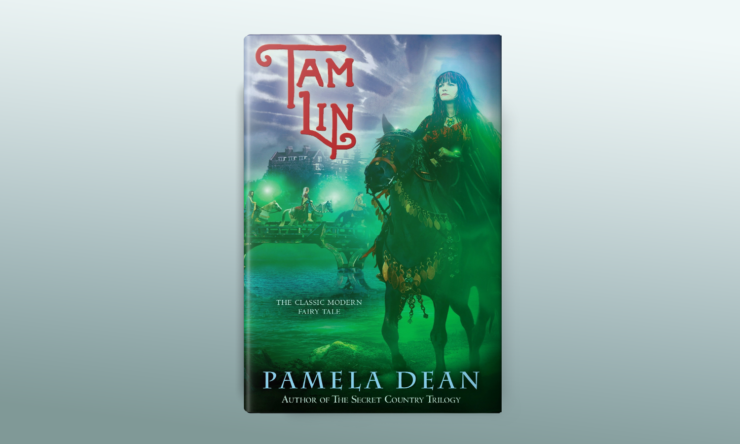

Tam Lin, by Pamela Dean, is one of those books that defies description in the best way, because it both is and is not a fantasy. For most of the book, it’s the story of a girl named Janet starting her college life, with all the changes and chaos that entails. She sees weird things on campus. Okay. Everyone sees weird things on campus. I was already taking classes at the community college across the street from my high school, and I’d seen a man with six squirrels on a leash, a woman attending all her classes in a ball gown, and a person we all called “Troll” whose wardrobe consisted mostly of chain mail and rabbit skins. College campuses are alive with weird things.

Only her weird things are very real, and eventually they make it clear that the book is a fantasy, and more, that Janet is in some pretty deep shit. Fun for the whole family! It’s a solid, well-written, remarkable book that stands up well to the passage of time, and is in many ways one of the foundations of urban fantasy as we know it today (which is a whole different, much longer article). Even if there had been nothing to recommend it but what I’ve already said, I would have loved it deeply, and revisited it often.

But Janet—smart, sensible, bibliophile Janet, who was everything I wanted to be when I grew up—loved poetry. She wrote a sonnet every day, “just to keep her hand in,” and the book followed the process of her composing one of those sonnets, tying it deftly into the narrative as a whole. I’ll be honest: I didn’t realize just how deftly into the fifth or sixth time I read the book, because I was too busy staring, wild-eyed, into space. I had found one of the pieces I needed to build the woman I wanted to be.

I had found poetry.

Everyone I knew wrote poetry: it was a class assignment handed out with remarkable frequency in the Gifted and Talented classes, it was a pass to the literary magazine and its vaunted extra credit points, it was a quick and easy way to impress teachers. And I already knew how to write sonnets, having been taught at a young age by an aunt who was trying to prove a point about child development and expectations. But I had never considered that I could just … write it. I could sit down and write a sonnet for no reason other than I wanted to write a sonnet.

As I write this, I have an old black binder covered in the sort of embarrassing bumper stickers that seemed utterly brilliant to me when I was fourteen. It’s so thick that it’s on the verge of bursting. I don’t think the rings would ever close again if I opened them now. It contains a high school education’s-worth of sonnets, one per day from the time I first read Tam Lin to the end of my school career. They’re all technically perfect, even if most of them are self-indulgent and derivative enough that they’ll never see the light of day. And toward the end of the four-year, 1,500+ (because sometimes I would get excited and write two) project, they got good. I may not be the next Shakespeare or the queen of the sonnet in the modern world, but I got good. That still amazes me.

Poetry is an incredibly important part of my life, and I don’t know if I would have that—the passion or the practice—if I hadn’t read Tam Lin when I did, when I was feeling receptive. It changed my world forever. (It also saved my life, thanks to introducing the idea of the conversational code word for “I need help, drop everything and come,” in the form of “pink curtains.” Without it, I don’t think I would be here today.)

Tam Lin is a book about choices and consequences, friendships and relationships, and the way our adult selves are built on the bones of the children we once were. It’s also about poetry. If Pamela Dean had never written another word, she would still deserve to be remembered as one of the greats, for this book alone.

Read it.

Originally published September 2016.

Buy the Book

Where the Drowned Girls Go

Seanan McGuire is the author of the Hugo, Nebula, Alex, and Locus Award–winning Wayward Children series; the October Daye series; the InCryptid series; the delightfully dark Middlegame; and other works. She also writes comics for Marvel, darker fiction as Mira Grant, and younger fiction as A. Deborah Baker. Seanan lives in Seattle with her cats, a vast collection of creepy dolls, horror movies, and sufficient books to qualify her as a fire hazard. She won the 2010 John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer, and in 2013 became the first person to appear five times on the same Hugo ballot.