Welcome to Close Reads! In this series, Leah Schnelbach and guest authors will dig into the tiny, weird moments of pop culture—from books to theme songs to viral internet hits—that have burrowed into our minds, found rent-stabilized apartments, started community gardens, and refused to be forced out by corporate interests. This time out, Hubert Vigilla contemplates the mysteries of the ring.

“Wrestling partakes of the nature of the great solar spectacles, Greek drama and bullfights: in both, a light without shadow generates an emotion without reserve.”

–Roland Barthes, “The World of Wrestling”“The invisibility spell doesn’t prevent you or your gear from emitting light, yet that light makes you no less invisible. The light appears to be coming from the air. Spooky! #DnD”

–Jeremy Crawford offering sage advice on Twitter

Wrestling is art. Beautiful yet brutal, at times comic and tragic. It’s theater, comic books, stunt work, dance, martial arts, and kung-fu movies. Wrestling has the capacity, like any artform, to move people to tears. (I’m looking at you, Sasha Banks vs. Bayley at NXT TakeOver Brooklyn.)

Wrestling is not “soap operas for men,” like it used to be called. How patronizing—soap operas are for everyone—and how limiting. There are so many kinds of wrestling: the pathos of old school southern promotions, the branded sports entertainment at WWE, the blood-soaked hardcore associated with CZW, the hard-hitting Japanese style, high-flying lucha libre in Mexico (sometimes these wrestlers work at intersections, essentially busking for those stuck in traffic), the technical focus in the UK, the indie supergroup feel of AEW and golden era NXT.

There’s one match from 2019 I think about a lot because it is an absurd work of fantasy: two invisible brothers duke it out in front of an adoring crowd.

The Invisible Man vs. The Invisible Stan – Joey Janela’s Spring Break 3 (2019)

Watching the Invisible Man vs. the Invisible Stan reminds me of the way Penn & Teller occasionally deconstruct a magic trick (e.g., this sleight of hand demonstration). This match is a strange kind of magic, and also a dumb kind of joke that everyone is in on. The total absence of visible wrestlers celebrates the different moving parts of wrestling as an artform.

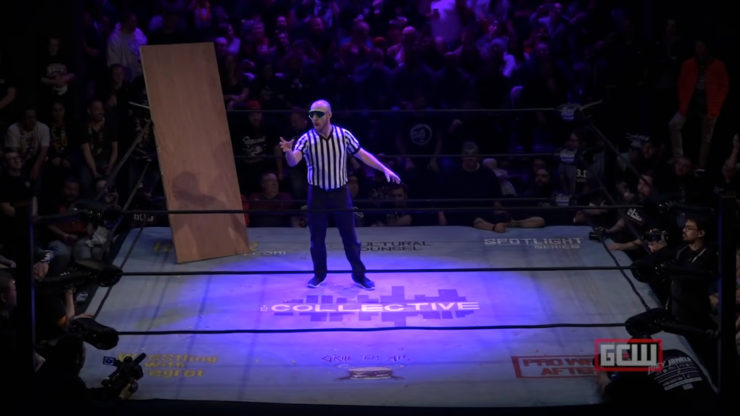

Notice the goofy conceit: referee Bryce Remsburg must put on special glasses to see the two invisible wrestlers. He then proceeds to pantomime their movements, implying what happened, sometimes through mimicry, and other times through reaction. He sells the illusion well, even requesting a better chair for a non-existent wrestler to sit on, and putting on rubber gloves when an invisible wrestler begins to bleed invisible blood. The commentary team renders this invisible action more visible, making explicit what could only be inferred in person and in the moment.

The rituals and tropes of wrestling remain even without the wrestlers. It’s the form without the content, or maybe it’s the content without the form.

This tussle between invisible combatants is like a coy take on Roland Barthes’ observation that wrestling is a kind of algebra that “instantaneously unveils the relationship between a cause and its represented effect.” Think of the Invisible Man and the Invisible Stan as missing integers in this peculiar equation, with everything around them providing the sum: _____ + _____ = 3:16.

Invisible Cities

Notice the crowd’s reaction to the Invisible Man vs. the Invisible Stan. The whole debate over wrestling being fake is moot.

Wrestling fans know this is storytelling, and they immerse themselves in the fiction of this world for the duration that the spectacle exists. Watch the fake high-fives during the entrances, or the sympathetic toppling over during the dive from the balcony. Wrestling fans aren’t marks being conned; they are confederates in the magic trick and essential to the illusion.

Peter Boyer at AIPT noted how fans make a match through their call and response chants. He wrote his appreciation of this invisible match during the pandemic, a time when wrestling was performed without large crowds. I think about a few matches during this time period and how they tried to play with the idea of limited attendance.

In the early period of the pandemic, Joey Janela and Jimmy Lloyd wrestled a hilarious social distancing match for GCW. Like the invisible match, Janela and Lloyd basically wrestled each other while leaving a few feet between them—more than enough space for the Holy Spirit. The lack of contact called attention to the expert physicality of wrestlers who know and love their craft. The decorum of social distancing during the pandemic in some ways reflects the unspoken rules of protecting your fellow wrestler in the ring.

There was also Go Shiozaki vs. Kazuyuki Fujita for Pro Wrestling NOAH. Filmed in an empty arena with just the camera and ring crew, the hour-long bout begins with a silent 30-minute staredown, the wrestlers almost completely still. Hanging between them, unspoken and unseen, is their long history of interpersonal narrative conflict as well as the uncertain moment of the world. It is a little bit Sergio Leone, a little bit Chantal Akerman, and still very much wrestling. (Later in the match, Fujita drinks hand sanitizer and spits it into Shiozaki’s face. How amazing and revolting.)

Oddly, my favorite match of this empty-arena era might be the Stadium Stampede match at AEW’s Double or Nothing (2020). Shot at TIAA Bank Field, home of the Jacksonville Jaguars, it is an anarchic multi-man wrestling match in an empty football stadium. From beginning to end, it is the best Jackie Chan movie since the early 2000s.

Like any artform, a formal constraint (lack of a live audience) can push artists to be more creative.

You Can’t See Me

There’s an old trope in wrestling (or maybe an old trope in modern wrestling fandom) that a great wrestler could carry a broomstick to a 3-star match. Essentially, a good wrestler knows their craft so well that they don’t just make their opponent look good, they could make an inanimate object look good. Or even an invisible opponent. Joey Janela has a history of wrestling invisible people, which culminated in two invisible wrestlers in a match. And, yes, Janela always made his invisible opponents look good.

This makes me think about DDT Pro-Wrestling in Japan and the wrestler Yoshihiko, a blow-up doll who is also a 17-year in-ring veteran. The Internet Wrestling Database has a list of Yoshihiko matches dating back to 2005, which includes a tag-team match against The Golden Lovers and multiple Battle Royale appearances. As a child watching wrestling, I would perform moves on a plush Pinocchio roughly my size, and what is Yoshihiko but a martial Pinocchio plush? Any time Yoshihiko is in a match, it can be a banger. Above is Yoshihiko vs. Kota Ibushi in an excellent display of humor and athleticism. Occasionally, Yoshihiko is helped by unseen assistants, like stagehands in a play whose presence the audience can ignore or puppeteers in a film removed in post-production. Adding to the oddness, Yoshihiko even has merchandise at Pro Wrestling Tees for those who don’t mind wearing something with a blow-up doll on it.

Yoshihiko is a real wrestler (in whatever way you wish to interpret that phrase) who makes his opponents look great. These moments of multi-party participation, suspension of disbelief, and fiction in wrestling are part of what make me love this artform so much. It brings attention to the physical prowess of those in the ring, the internal logic of a story, and all the peripheral material that goes into the creation of something intended to be real.

I could go on about the most illegal move in wrestling (which is not what you might expect), or that time Kenny Omega wrestled a 9-year-old-girl, yet this high-level artifice brings me back to the event that got me back into wrestling.

Like so many lapsed fans of a certain age, I thought that CM Punk’s unscripted pipe bomb promo in 2011 was the most compelling thing about wrestling (or at least the WWE) in a long while. A star at the independent wrestling promotion Ring of Honor, he was signed to the WWE in 2005. He didn’t fit the mold of the company’s homegrown stars, and often felt stifled by the heavy scripting and the limited style of wrestling.

It’s cliche by now, but at the time it was so refreshing to watch him sit cross-legged at the entrance ramp and air grievances about the backstage politics of wrestling. Notice how the pipe bomb is delivered outside the ring rather than within the ropes as Punk acknowledges the unseen wrestling world. This moment merged generations of oft-cited wrestling history, like the clashes between Steve Austin and Vince McMahon and the over-cited Montreal Screwjob. Punk wasn’t just a darling wrestler of the indie scene. It is that moment when a fictional character/heightened persona is both particular and universal. The monologue spoke to all disgruntled employees frustrated with management that makes them feel invisible. Such a moment of mundane workplace grievance was made manifest through the anger and text of the wrestling artform outside of the ring. (Ironic that John Cena, the company’s biggest star at the time, used the catchphrase “You can’t see me.”)

Following a title reign and floundering creative decisions, the ensuing drama between CM Punk and WWE included (1) Punk getting fired by the WWE on his wedding day, (2) Punk’s appearance on fellow wrestler Colt Cabana’s Art of Wrestling podcast that revealed how burnt out and broken he felt working for the company, (3) a WWE physician suing Punk and Colt Cabana for defamation, and (4) Cabana and Punk suing each other over a verbal agreement made during the defamation lawsuit.

Wrestling is an art, but the wrestling business is something else and something uglier: a business.

Darkness Visible

In the artifice of wrestling as a whole, I can’t help but return to the real, the actual, the truth. Wrestlers may do their best to protect each other from harm, but it still hurts to get chopped in the chest, or to have a body drop on you from the top rope, or to tumble onto a thin mat covering the concrete outside the ring. And it hurts to be disregarded or mistreated, and to feel betrayed, and to lose friends. In some ways, the real world is not as safe as the art safely practiced in and around the ring.

After winning the AEW Championship at the recent Double or Nothing pay-per-view, CM Punk re-injured his knee. It wasn’t from taking a bump but rather from diving into the crowd before a match and clanging against a guardrail. He then wrestled a match. Though not readily apparent, you can see him favor his leg if you know what to look for. If you watch long enough, you can see when people fall wrong or are wrestling rattled. Yet sometimes people hide their maladies too well. Kenny Omega, for instance, has put on classic matches while experiencing spells of vertigo. How? Seriously, how?

Cody Rhodes also wrestled a match while injured at the recent Hell in a Cell pay-per-view. Reports are that he tore his pectoral muscle clean off the bone. Working hurt is an old school mentality, and so many wrestlers concealed the years of damage to their bodies. Over the weekend, you couldn’t unsee Cody Rhodes’ chest. Yet that darkened blood tumescing beneath the skin and spreading called attention to tattoo, “Dream,” on the other pec in honor of his father, Dusty Rhodes. Reckless or not, Cody and Seth Rollins put on a 24-minute masterpiece that would have made Dusty proud.

Are these are characters or are these are real people? Is this all just a story, or is it true?

Those either/or distinctions breakdown after a while. Or at least the art of wrestling makes me reconsider them. Why not both? Why not just “yes”?

“This grandiloquence,” Barthes wrote, “is nothing but the popular and age-old image of the perfect intelligibility of reality.” And to that, I now see a common quality about the comic match between two invisible people, the tragedy of a person made to feel invisible, and toll that making art can take on the bodies of artists. Each spectacle, in its own way and its own terms, allows an unseen world to become temporarily visible.

Hubert Vigilla is a Brooklyn-based writer whose fiction has appeared in The Normal School, No Tokens, Territory, and elsewhere. You can follow him on Twitter.