Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

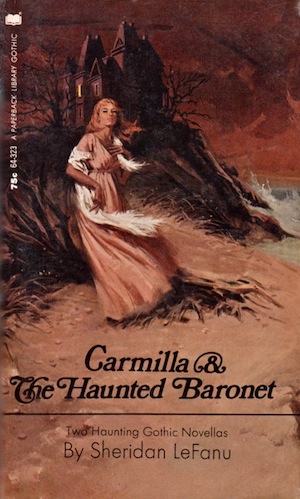

This week, we continue with J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, first published as a serial in The Dark Blue from 1871 to 1872, with Chapters 13-14. Spoilers ahead!

“You may guess how strangely I felt as I heard my own symptoms so exactly described in those which had been experienced by the poor girl who, but for the catastrophe which followed, would have been at that moment a visitor at my father’s chateau.”

We left General Spielsdorf and his ward Bertha rejoicing that Millarca had found her way safely to their home. Soon, however, he noticed some “drawbacks.” Millarca complained of languor and never emerged from her room until afternoon. At the same time, she was repeatedly seen walking outside, as if in a trance, in the first light of dawn. Spielsdorf believed she walked in her sleep; the puzzle was how she got out of her room while leaving the door locked from the inside.

A more pressing concern was Bertha, who began to sicken. First she dreamed of a specter sometimes resembling Millarca, sometimes a beast, stalking at the foot of her bed. Strange sensations followed, as if an icy stream flowed against her breast, as if two needles pierced her below the throat. Later she’d feel strangled to the point of unconsciousness. Laura listens in silent amazement to this description of her own symptoms and of his guest’s peculiarities, so similar to Carmilla’s.

They arrive at the ruined village and explore Karnstein castle. Spielsdorf recalls the “bloodstained annals” of the extinct family and says that even after death they “continue to plague the human race with their atrocious lusts.” He points out the freestanding chapel, in which he hopes to find the tomb of Countess Mircalla. To his friend’s remark that they have a portrait of Mircalla at home, Spielsdorf claims he’s seen the lady herself. She’s not as dead as one might fancy: He has one last duty to perform in life, and that’s to avenge Bertha by decapitating her assassin!

In the chapel, before Spielsdorf can finish his story, they hear a woodman working nearby. The man can’t tell him about the Karnstein monuments, but does know how the village came to be deserted. It was troubled by “revenants,” who after killing many villagers were dealt with according to law: their graves opened, their heads severed, their bodies staked and then burned. Still the plague continued. A “Moravian nobleman” experienced in vampire extermination offered to help. He hid in the chapel tower and watched a vampire emerge from its grave, laying aside its shrouds as it left. By stealing the shrouds and taunting the vampire with them, the Moravian managed to tempt it to the top of the tower and kill it.

This same nobleman had authority from the surviving Karnstein to remove Mircalla’s tomb. He did it so well that no one now remembers where its site was. Rumor holds that her body was also removed.

The woodman leaves to fetch a forest ranger who may know more, and Spielsdorf resumes his story. As Bertha declined, he summoned a physician from Gratz. The consultation ended in their personal doctor ridiculing the visitor as a “conjuror.” Privately, the Gratz doctor told Spielsdorf that he couldn’t be mistaken, as “no natural disease exhibited the same symptoms.” Bertha was near death, but could be saved if Spielsdorf heeded the letter the doctor left with him—to be read only with the nearest clergyman available. Meanwhile the doctor would consult with a man “curiously learned” in Bertha’s complaint.

Spielsdorf ended up reading the letter alone. If he wasn’t so desperate, he’d have dismissed it as a lunatic’s ravings. The Gratz doctor insisted that the livid mark near Bertha’s throat proved she was the victim of a vampire! Moreover, all her symptoms indicated such a visitation. Though skeptical, Spielsdorf acted on the doctor’s instructions. He concealed himself in Bertha’s dressing room, sword at hand. From there he watched an ill-defined black presence crawl up the bed to Bertha’s throat, where “it swelled, in a moment, into a great palpitating mass.” When he sprang out to attack the creature, it contracted into the shape of a glaring Millarca! He struck in vain; instantly she was at the door, unscathed. A second blow shivered his sword against the door, for Millarca had vanished. At dawn, Bertha died.

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

Spielsdorf breaks down. Laura’s father discreetly walks away. Laura remains in the dim chapel, horror stealing over her as she considers how closely the General’s story bears on her own case. She’s relieved to hear the voices of Carmilla and Madame Perrodon outside, and gladly watches Carmilla enter. Her friend’s “peculiarly engaging smile” undergoes “an instantaneous and horrible transformation” as Spielsdorf cries out and lunges at her with the woodman’s abandoned ax in hand. Carmilla dives under his blow and seizes his wrist with uncanny strength, forcing him to drop the ax. In the next moment Carmilla is gone. Madame arrives and asks where Carmilla’s gone, though Carmilla must have left by the same passage Madame has just come through.

“She called herself Carmilla?” the deeply shaken General asks. Laura confirms it. That is Millarca, Spielsdorf says, who was long ago called Mircalla. He commands Laura to leave “this accursed ground,” drive to the house of the priest, and stay there until he and her father follow. May she never see Carmilla more!

This Week’s Metrics

By These Signs Shall You Know Her: Laura and Bertha both report the piercing needles, the sense of strangulation, and the livid mark that Bertha’s doctor recognizes as diagnostic. Also, languor remains a clear indicator of vampirism.

The Degenerate Dutch: Sheridan Le Fanu makes no attempt whatsoever to spell out the “patois” of the “rustics” around Schloss Karnstein. My gratitude is unbounded.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The general admits that doctor who provided a second opinion on Bertha was hard to believe, his letter “monstrous enough to have consigned him to a madhouse.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

A man who goes on a journey of revenge against a vampire must first dig zero graves. He may, however, find himself digging up graves along the way, which is a different story and probably a different proverb.

The General seems well-prepared for as much digging as is required. Though not quite prepared for his quarry to suddenly poke her head in! Nor was Carmilla, it seems. Don’t you just hate it when you’re talking about a person and they suddenly walk into the room? Or the abandoned chapel? Almost as bad as when you wander into a chapel, expecting to catch up with your latest lover/victim, only to see the guy who scared you off the last one.

Poor Carmilla. Or not.

This week, we finally get several things we’ve been waiting for. Laura recognizes her own experiences in the General’s story (Good!), but seems to have missed the implication that Carmilla is bad news (Not good!). At least until the fact of it is shoved in her face. It’s hard to admit that your best friend is an undead fiend of the night. The General reveals the remainder of his story—and the last nail in the coffin, so to speak, is his reaction to meeting Carmilla and her reaction in turn. All is revealed!

Or is it? Which is to say, are Chapters 13-14 intended to come as a revelation to the reader, or only the characters? We’ve had plenty of foreshadowing, down to older-Laura telling us that Carmilla was a monster—but in 1872, readers are perhaps less familiar with the signs indicating exactly what kind of monster. And Le Fanu can’t always be counted on to provide predictable answers even for the genre-savvy: “the evil monkey is a caffeine hallucination” hasn’t exactly turned into a genre trope, for example.

A great number of people who are not Laura do appear familiar with her ailment. Bertha’s second doctor for one, and possibly Laura’s own uncommunicative doctor for two. And the “rustics” who preserve the traditions of long-dead great families, not to mention the instructions for dealing with those great families when they develop, shall we say, refined tastes. This is totally a metaphor.

Even after the nobles are long-dead (or at least, mostly long-dead), it’s important to remember those instructions for dealing with revenant troubles. The woodsman discusses it as a matter of practicality and law, a pragmatic approach much to be appreciated when the revenants in question are such thorough romantics. He’s also the first character to use the V-word.

Was that word familiar to most readers, or the equivalent of asking if you’ve ever heard tell of a shoggoth? Google Ngrams shows pretty much a flatline on “vampire” until the late 60s, but it also suggests “shoggoth” at a similar flatline today, and I certainly know one when it oozes its way onto the page. Even if the “great, palpitating mass” is occasionally just a vampire having a little trouble with her transformations.

However startled they may be, we’re fortunately in the company of at least one character prepared to do more than gibber. The General has excellent reflexes. Even if Carmilla’s escaped them for now, she’s going to have trouble retreating into her innocent act. Next: revenge!

Anne’s Commentary

Instead of so blandly entitling Chapter XIV “The Meeting,” Le Fanu should have called it, “At Last, Carmilla Kicks Some Patriarchal Butt.” Oh all right, the General does have a legitimate grievance, and he seems like a good guy overall. Still, you go, girl. Nobody puts Carmilla in a corner with an axe lodged in her skull or through her lovely throat. And right in front of Laura, too, whom Spielsdorf has already harrowed up more than you’d think he ever would a delicate maiden like her.

Oh all right. If you get a shot at Carmilla while she’s smiling endearingly, semi-unguarded, I guess you have to take it.

And maybe the General shows Laura a certain respect by not pulling any narrative punches (or axe swings) in over-deference to her nerves (as Daddy has done.)

One thing for which I have to take Laura to task is greeting Carmilla’s entrance to the chapel with relief and joy. She’s started realizing, from the General’s tale, that the resemblance of Millarca to Carmilla verges on identity. Shouldn’t she therefore anticipate that the meeting between Spielsdorf and Carmilla will escalate the tension in the room rather than dissipate it? Shouldn’t she either tremble at the prospect or run out and warn Carmilla away?

Laura might argue in retrospect that she was so firmly bewitched by Carmilla that she couldn’t quite connect the dots of Spielsdorf’s revelations. Or maybe, subconsciously prompted by her survival instinct, she wants Spielsdorf and Carmilla to meet?

Anyhow, Le Fanu has set his stage well for the climax of this scene. The woodman has conveniently left his axe behind while he fetches a more knowledgeable local. And Daddy has wandered off—he would have made an awkward fourth to the encounter.

Apart from Carmilla kicking butt, my favorite part of this week’s reading is the woodman’s history of the fall of Karnstein Village. What caused it? Vampires! The woodman doesn’t know (or doesn’t tell) what started the plague of bloodsuckers, but many a villager was killed and many a revenant tracked to its grave and dispatched “according to law.” Decapitation, staking and burning are all traditional methods of exterminating vampires. What was new to me was how the Moravian nobleman lured his vampire to its final death. In his honor, let’s call it the Moravian Shroud Gambit. Wait for the vampire to emerge, when it will of course shed the cerements of the grave as (1) too confining for surface wear and (2) too obvious an indication that the wearer is technically dead. Snatch the vampire’s wrappings the way you might a skinny-dipper’s clothes, thus really pissing it off. Obviously, the skinny-dipper doesn’t want to walk away from the swimming hole buck-naked, but why does the vampire need its shroud?

I know of the tradition/trope that a vampire needs to rest in its home earth, or at least with some home earth it carries on its travels abroad—as in the multiple dirt-filled boxes Dracula ships to England ahead of his visit. I went searching for shroud-tropes and found this article of interest. Evidently people disinterring a corpse would sometimes find that the shroud that had covered their face was missing (bacteria-decayed). The corpse’s teeth might be exposed, leading to the notion that it had devoured the cloth. Which meant it must be undead. Which indicated that vampires (“shroud-eaters”) must require such sustenance as a baby requires milk. To kill them, you had to get the shroud out of their mouths and replace it with something inedible, like the bricks that have been discovered shoved between the jaws of suspected revenants-to-be.

Or maybe Le Fanu’s vampire would just have been too cold underground without its linens?

Anyhow again. Who is this Moravian guy, and what’s his game? The woodman at first implies he just wandered by chance into the neighborhood of afflicted Karnstein. Then he says that the Moravian had been “authorized” by the reigning Karnstein to remove Mircalla’s tomb. Remove it to where? Another part of the chapel or village area, in order to hide it? Or farther away? And did he also remove her body? Nobody knows for sure, according to Woodman. Nobody living, anyway. Huh. My Kolchak-senses tell me there’s quite the story here.

My last pondering is about the reproductive strategy of Le Fanu’s vampires. How any given “species” of vampire generates more vampires is an important consideration. If everyone bitten returns as a bloodsucker, your vampire population is going to explode exponentially. If the vampire has to choose to make a given victim a vampire, often by feeding the victim some of its own blood, then vampires can control their numbers, create exclusive societies.

If everyone Carmilla kills becomes a vampire, then all those plague-dead peasants around Laura’s schloss should be revenanting. Which they don’t seem to be doing. Maybe the other peasants are exercising the time-honored methods of “pre-sterilizing” victims, you know, by cutting off their heads, stuffing their mouths with garlic or bricks, staking their bodies down. No mention of this, though.

I don’t think aristocratic Carmilla would want a lot of ragtag baby vampires around, so say she gets to pick her fellows in undeath. Laura’s definitely on her list to experience all the dark joys and tribulations of vampirism. But what about Bertha?

Unless Carmilla was interrupted before she could properly “seed” Bertha, might not the General go home to a reunion with his dear ward? That would be cool. Only he, enlightened to the ways of the vampire, would probably have taken prophylactic measures before traveling to Laura’s Dad’s place.

The patriarchy never lets vampire girls have any fun, sulk, sulk.

Vampires aren’t the only hazard wandering eastern Europe. Join us next week for Clive Barker’s “In the Hills, the Cities.” You can find it in Barker’s The Books of Blood, Volume I.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out July 26th. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Another enjoyable and insightful entry. I agree that there’s a lot of story untold in the final chapters of “Carmilla” regarding the history of the Karnstein family and village, and especially the identity and background of the Moravian nobleman. Thank goodness for Hammer Studios and their films which filled in many of these details in their own unique way. Was Captain Kronos a Moravian, I wonder.

All the potential swashbucklers I can think of for the Moravian are from the wrong time periods, but it sure sounds like someone has crept in to do a cameo.

Laura is either too much under Carmilla’s spell to realize how things are going to go or she has enough of her father’s attitude towards the supernatural to think that, no matter what the General seems to be implying, he and Carmilla won’t recognize each other and everything Laura thought was being implied will turn out to not be the case. Denial reigns.

As to references to vampires, the book The Vampyre was a big success in 1819. Charlotte Bronte referred to vampires in Jane Eyre (although she thought Bertha Rochester looked like one. Carmilla would be horrified at the comparison). Dumas, in The Count of Monte Cristo, has people suggest the Count and Haydee could be vampires. Those books were both in the 1840’s, so most readers should have known the term.

Enjoying this re-read (or first-time read) and all the thoughtful insights immensely! Weirdly, “shrouds” was the word of the day, with a new Cronenberg movie that will include grave vandalizing and speaking to the dead: https://variety.com/2022/film/markets-festivals/vincent-cassel-david-cronenberg-the-shrouds-filmnation-cannes-1235263784/.

I wonder if the equally on-the-ball doctors who examined the late Miss Bertha and Miss Laura herself might, in fact, be the self-same medic? (I’m not sure if the geography & timing work, but it certainly makes sense that neighbours and old chums would share the same Doctor – who would definitely boast an excellent rating on the Van Helsing scale, having identified the work of a vampire and set in motion the events leading to it’s final death).

Admittedly I am also keen to identify one of the woodmen/rustics with the father of the young girl whose funeral ‘Carmilla’ finds so provoking; it would be a nice bit of Justice, if nothing else.

Also, one admires Old Spielsdorf for his direct approach to dealing with the undead – it’s interesting to note that Carmilla, while clearly inhumanly strong, is highly reluctant to engage in close combat (Even during that night time encounter in Bertha’s bedroom, when her powers would likely be at their peak); I wonder if this is product of her apparent desire to, if not ignore, then downplay her nature as a blood drinking monstrosity even in her own self image?

Oh, and for my money those wondering what happened to Countess Karnstein’s coterie need look no further than General Spielsdorf and his burning outrage at the fate of his ward – it’s not impossible they escaped him, but still entirely possible that he and his new friends hunted that party down while ‘Carmilla’ lay low.

Also, I’m not going to lie, that little mention of the Fall of Karnstein is thoroughly evocative: it sounds almost like something out of a CASTLEVANIA game, except that the Authorities are clearly on the ball (Also, one can only wonder if the Moravian Shroud Gambit worked mostly because the vampire in question was powerful, feared and arrogant enough that learning some puny mortal had disturbed their tomb provoked a thoughtless fury at such insolence).

As for the Moravian himself, I believe his identity will be made reasonable clear in future chapters (and his status as protagonist in the coolest Vampire Hunt novel/novella we never got to read is absolutely cemented).

I say no more … for now.

Ellynne @@@@@ 2: Awesome – so this is more of a “how will the reveal go” situation than a reveal-to-the-reader! As is frequently the case, shocking twists remain overrated.

Why aren’t there fewer Austin and Bronte zombie pastiches, and more vampiric pastiches? Admittedly, I speak here as an old-school World of Darkness nerd, who can basically never get too much subtle politics or razor-blade etiquette in my vampire stories.

Ellynne @2 R.Emtys @5 I had the same question a couple months ago and did some reading. It seems in this period vampires were almost more popular on stage than on the page, in part because they were an excuse to use all sorts of trap doors and stagecraft to make them appear and disappear. Apparently the trapdoors developed in the 1820s were actually called “vampire traps”. Very little was set in stone re. the rules of vampirism, except that they seemed to be more powered by the moon than harmed by the sun, and had an ethereal quality. So Carmilla teleporting around and appearing as a black cloud are very on-brand (and maybe inspired by the stage?). Likewise, it seems every vampire story needed a vampire expert to show up and exposit in the third act, which hasn’t seemed to change. (Credit to Nina Auerbach). I do feel that Le Faun was just about done with these characters at this point, because everything is moving very quickly and conveniently.

@6. Matt Sanders: As Doctor Polidori’s THE VAMPYRE goes to show, vampire stories where an expert does not show up do exist … and the lead characters tend to suffer very, very unhappy fates.

Heck, just look at NOSFERATU!

Oh, and for those who are interested in next week’s read but don’t have vol. I of Clive Barker’s Books of Blood, the story ‘In the Hills, the Cities’ can also be found in The Weird.

And that was definitely Captain Kronos.

But was the Good Captain time-travelling or is he an immortal?